On July 16, 1899, a small group of motormen and conductors for the Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) street car lines went on strike. These men left their empty cars stalled in the road, and then, in some instances, used dynamite to blow them up.

Not wanting a repeat of the deadly riots that took place during the January 1895 BRT strike, the New York City Police Department immediately sent 25 patrol wagons from Manhattan and the Bronx to Brooklyn to rein in the trouble-making strikers. As it turns out, the police weren’t needed for long. A large number of workers refused to go out this time around, and the strike came to a quiet end within a week.

For the policemen of Manhattan’s Leonard Street Station — aka the new Eighth Precinct — doing strike duty in Brooklyn meant spending a lot of time riding on the operational trolley cars looking for trouble. It was during this week that they “adopted” a big, brown, half-starved shaggy dog (sort of a cross between a Newfoundland and a setter) who would change their lives for the better. They named him Strike.

Right from the start, Strike was on the job with his fellow police officers. As the men road back and forth on the trolley lines, Strike would leap from the car and start biting or barking at any strikers causing excitement. To reward this stray dog for his duties, the policemen of the Eighth Precinct brought him back to Leonard Street, ordered a collar with his new name, and had him properly licensed.

Strike’s Daily Routine

Every morning, Strike would attend roll call by sitting at the sergeant’s desk and waiting for all the men’s names to be called. During the day, he spent a lot of time outside the station, where the neighborhood children would gather to play with him.

Strike liked the children, but his favorite people were the uniformed police officers (the plain clothes officers had to be at the station quite a while before he’d warm up to them). He also liked all the restaurant keepers within the boundaries of the precinct — especially those he had “trained” to feed him. (Unlike Jiggs, the jelly-belly fire dog of Brooklyn’s Engine 205, Strike did not put on the pounds from all the food.)

Three times a day, Strike would visit his favorite restaurants (he’d mixed it up so he wouldn’t wear out his welcome), and wait for someone to bring him a package of meat scraps tied with string. Placing the string in his mouth, Strike would carry the food back to the police station, where an officer had to properly lay it out in his favorite eating spot in the back room. Sometimes the officers would give him a nickel, which he would carry to the bakery to purchase his favorite ginger cake.

One day about five years after Strike moved into the Leonard Street station house, an officer found a Newfoundland on the downtown platform of the Chambers Street elevated station. The dog had a collar that said “J.J. Atkinson, Raymond, Lafayette. ” The poor dog was running about as if he had lost his master and was hunting for him.

The police thought the dog must have come from Lafayette, N.J.; I hope they eventually realized that there was a J.J. Atkinson saloon on the corner of Raymond Street (now Ashland Place) and Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn!

The policeman brought the dog back to the station house, where he stayed for quite a while (courtesy of Captain Dennis Sweeney). During this dog’s extended visit, Strike learned to bark longer and louder in order to encourage the waiters to give him more food so that he could share his meal with his new canine friend.

Strike Makes a Few Collars

Over the years, Strike assisted in many arrests. One time when a prisoner tried to escape the station house, Strike grabbed him by the coattails and dragged him back. Another time he helped Policeman Cleveland capture two vagrants who had been begging throughout the district for some time.

As the story goes, Strike was asleep on the rug under the sergeant’s desk when he heard the rapping of a policeman’s club outside. He and Policeman Brennan ran outside the station and got a glimpse of Policeman Cleveland in pursuit of two men dressed in United States Navy uniforms. Strike took off and caught one man by his trousers while the officers caught the other man. Both men were charged with vagrancy (they weren’t actual sailors).

Strike was also skilled in delivering notes for the men. If he was out with a roundsman and the officer wanted to send a message to the station house, Strike would carry the note in his mouth to the sergeant and return promptly with an answer, if there was one.

Strike Rescues a Few Kittens

Although Strike was known as a cat hater, that all changed on the night of June 8, 1906. According to the news reports, at about 8 p.m. while walking home with his dinner on Hudson Street, Strike came upon a cat and dog fighting. Apparently, the mother cat had been nursing her kittens in a doorway when the dog attacked and killed her.

With three motherless kittens staring up at him, Strike dropped his meat package, tackled the bulldog, and put one of the kittens in his mouth. He carried the kitten to the back room of the police station where several policemen were playing dominoes, dropped the kitten at their feet, and ran back out. A minute later, he returned with the second kitten.

On his next trip out, Roundsmen Borener and Saul followed him to 78 Hudson Street, where they found Roundsmen Blohm bending over a dead cat and dog. Strike took charge of the third kitten and carried it back to the police station.

A month later, the kittens were still at the station house. On sunny days, they could be seen on the steps tumbling all over their canine caregiver and demanding his attention.

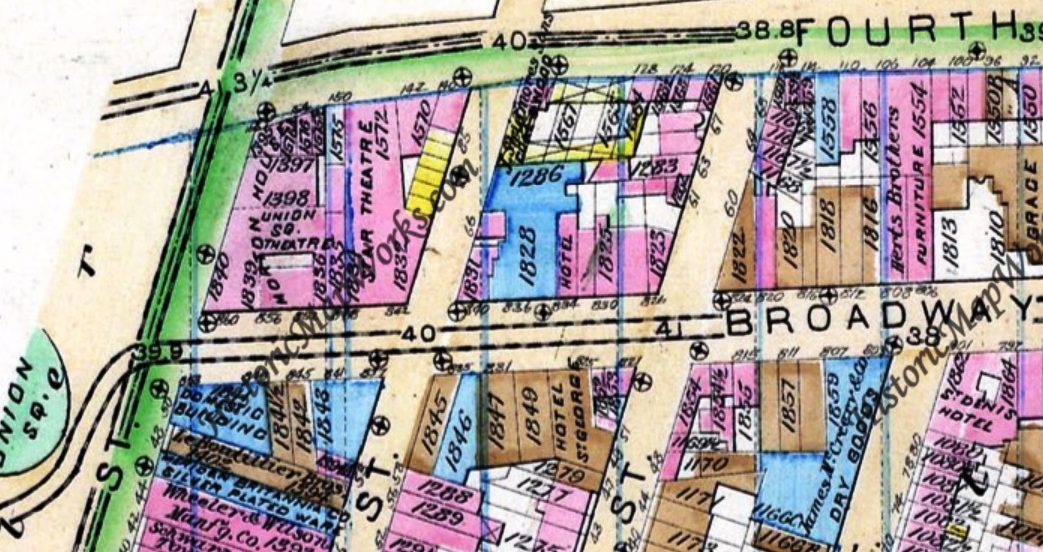

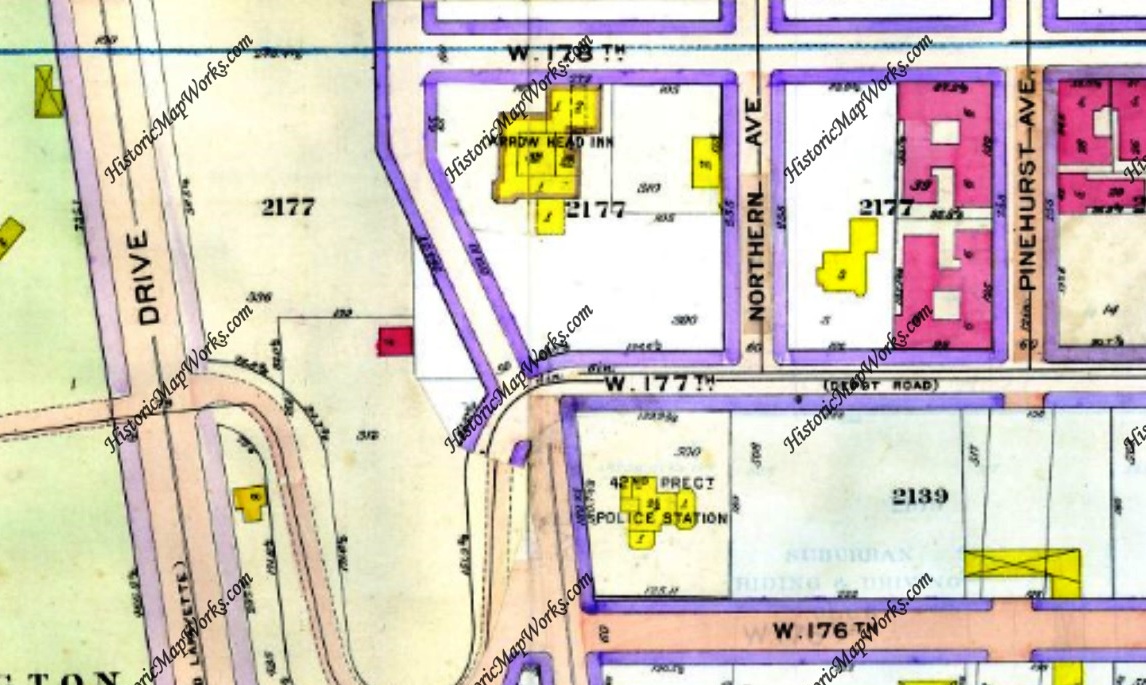

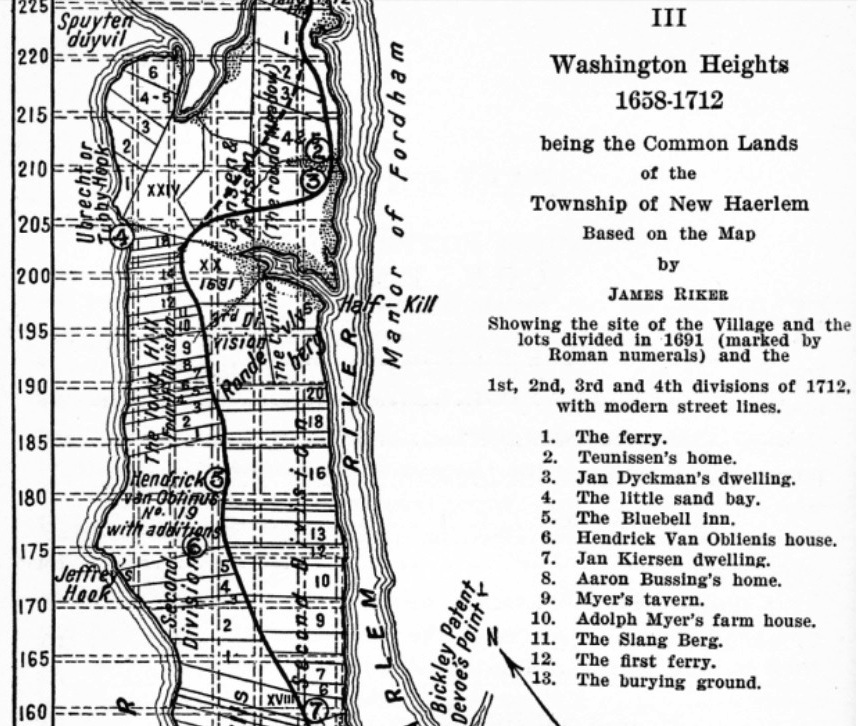

A Brief History of the Leonard Street Police Station

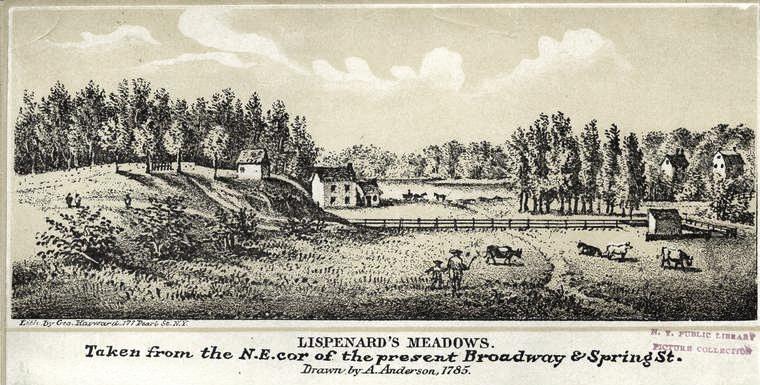

Throughout the seventeenth and most of the eighteenth centuries, the area of Manhattan that we call Tribeca was open land, much of which was held by Trinity Church (to the west) and by Anthony Rutgers (the swampland to the east). In 1741, Leonard Lispenard, a leaseholder of a large tract of land belonging to Trinity Church, married Rutgers’s daughter Elsie.

After Rutger’s death in 1746, most of his holdings went to Leonard and Elsie, and the large area to the east became known as Lispenard’s Meadows. Leonard Street between present-day Hudson Street and West Broadway was the southern tip of the meadows; the center of the meadows is about where Lispenard Street is today.

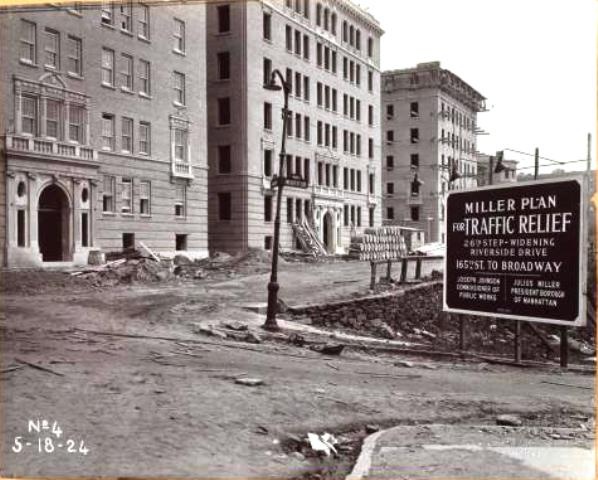

Leonard Street was laid out around 1797 as a twenty-seven-and-a-half-foot-wide street and ceded to the city in 1800. It was widened in 1806 and immediately developed with frame and masonry residences, none of which remain standing today.

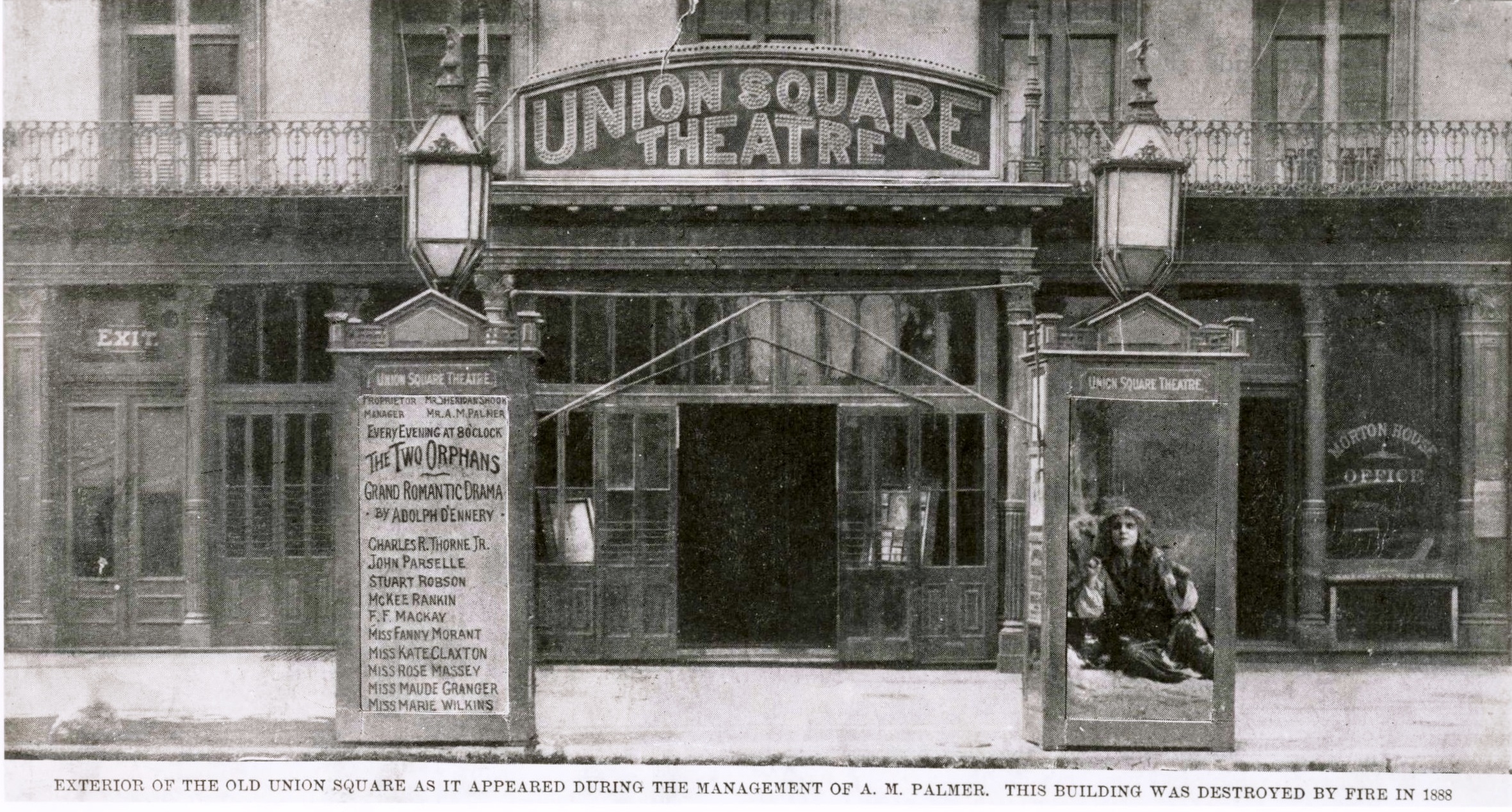

19-21 Leonard Street

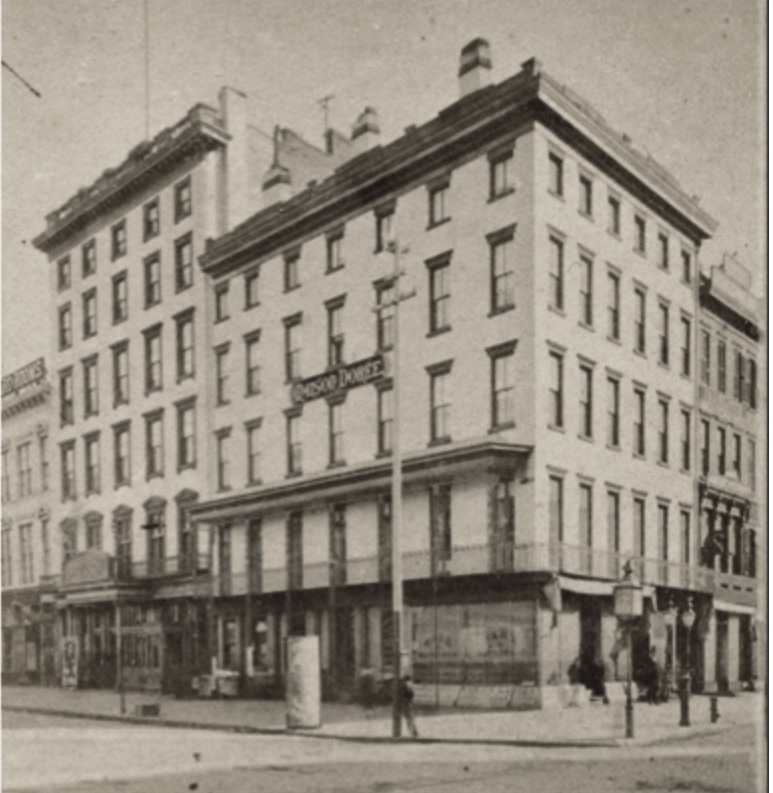

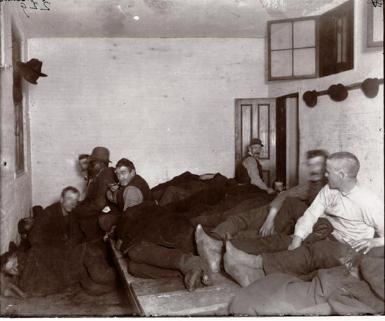

Designed by Nathanial D. Bush as a police station and prison for the City of New York, 19-21 Leonard Street was constructed in 1868 on two lots previously occupied by masonry residences. The four-story Italianate building of red brick and white stone trim also featured apartments for lodging indigent persons.

The station house was occupied by the Fifth Precinct — renamed the Eighth Precinct in May 1898 — which had previously been stationed at 49 Leonard Street. The Fifth Precinct was bounded by Warren Street, the west track of the West Street Railroad, Canal Street, and Broadway; it was also known as “the dry goods district.”

As Strike got older, the hot summers took a toll on him. By 1908, he was about 17 years old and had lost almost all his teeth. Following several illnesses, it was decided that it was time to put him out of his misery.

Strike Leaves This World

On September 13, 1908, Lieutenant Von Beborsky was called on to humanely dispatch the beloved mascot.

Five years after Strike’s death, on December 1, 1913, the precinct was abolished and the building was vacated and converted for commercial use.

Over the years, occupants have included Cordley & Hayes Corporation, the Standard Rice Company, the Ronald Paper Company, the Hailer Elevator Company, and the Empire Elevator Corp. Today the old station house at 19-21 Leonard Street — where policemen, vagrants, prisoners, cats, and a dog named Strike once converged — is a condominium with five apartments.

For more on the history of 19-21 Leonard Street, check out Daytonian In Manhattan, who, ironically, posted a story about the station house the same day as I posted mine.