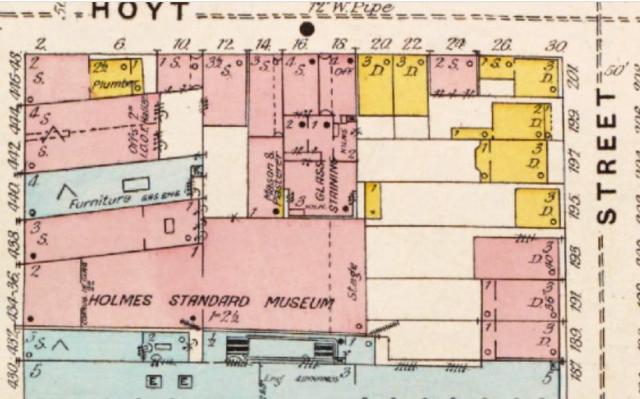

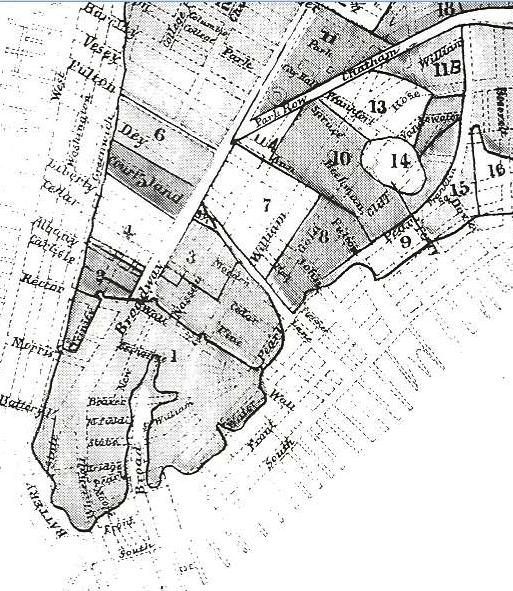

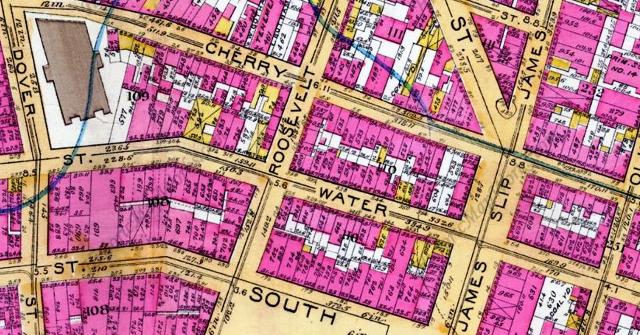

Roosevelt Street ran east-west between Park Row and South Street. The street was named after either Nicolas or Jacobus Rosenvelt, the son and grandson, respectively, of the first Roosevelt in North America–Claes Maartenszane van Rosenvelt–who arrived in New Amsterdam around 1649. Today this land is occupied by the Governor Alfred E. Smith Houses.

Roosevelt Street ran east-west between Park Row and South Street. The street was named after either Nicolas or Jacobus Rosenvelt, the son and grandson, respectively, of the first Roosevelt in North America–Claes Maartenszane van Rosenvelt–who arrived in New Amsterdam around 1649. Today this land is occupied by the Governor Alfred E. Smith Houses.

Once upon a time, before all the streets and buildings of New York City’s “deep East Side” were razed to make way for new public housing projects, there was a little colonial-era street just north of the Brooklyn Bridge called Roosevelt Street.

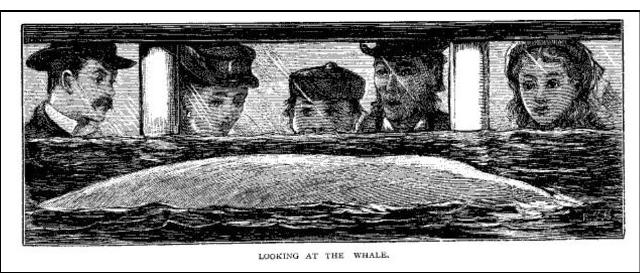

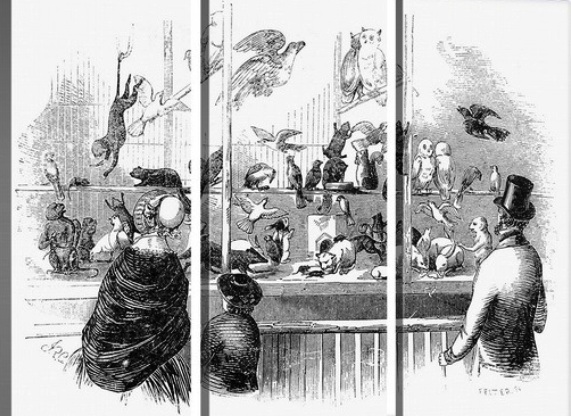

In 1875, Donald Burns, a veteran circus man and dealer in birds and wild animals, established his business at 115 Roosevelt Street, on the southwest corner of Water Street. Over the next 20 years, this little two-story red-brick building would serve as a temporary home for all kinds of birds, reptiles, and mammals, including panthers, parrots, pythons, swans, and a manatee.

The son of Scottish immigrants John Burns and Annie McGilrey, Donald Burns was born in Canada around 1840. He honed his skills as a trapper and survivalist in the Ontario wilderness at a very young age, and by the time he was in his late teens, he was trading furs in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and selling bob cats, raccoons, and other animals to traveling circuses and menageries throughout Canada.

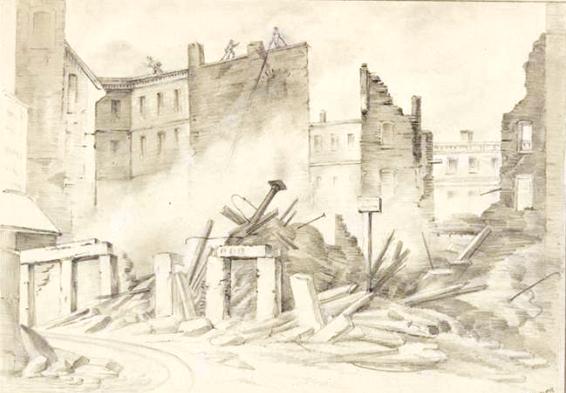

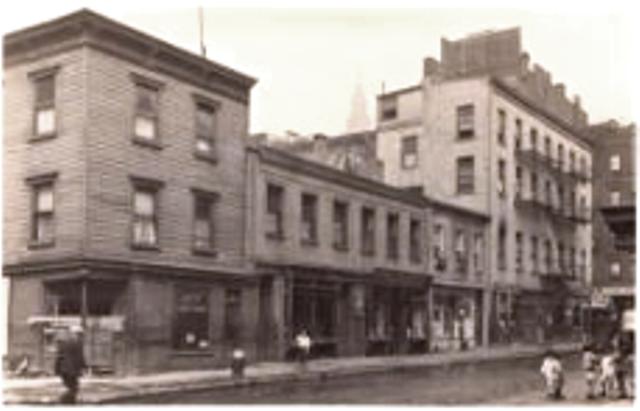

Donald Burns was long gone when this photo was taken on Roosevelt Street in 1927. The three-story frame building on the corner is 318 Water Street. Just to the right is 115 Roosevelt Street, where Rosy the Manatee, 90 swans, several panthers, 11 wolves, and numerous birds and snakes made their home from about 1875 to 1895. Previously, this old building housed a jewelry store owned by Henry R. Winstanley (1840s.) New York Public Library Digital Collections

Donald Burns moved to New York City just after the Civil War ended. He opened his first retail business in 1866 at 428 Broadway, where he sold small birds, chickens, dogs, and other small animals to the general public. About a year later, Donald moved his bird and animal shop to 612 Broadway, on the corner of West Houston Street (today the site of a six-story glass office building constructed in 2003).

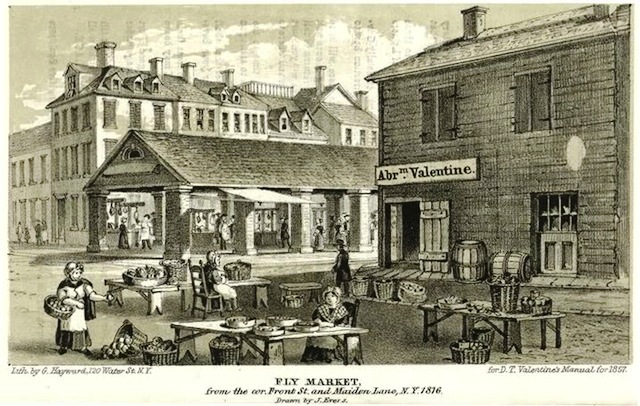

Sometime around 1868, Donald expanded his business by joining forces with J.B. Gaylord at 280 Front Street near Roosevelt Street. It was here that he began his wholesale animal trade.

Located just one block from the East River and the shipping piers, Donald could easily commission sea captains who were going to Africa, South America, and India to bring back exotic birds and animals, which he would in turn sell to more established New York animal dealers such as Henry Reiche and Archibald and John Reeves. The location also allowed him to export American deer, moose, and caribou to private zoological parks in Europe.

Donald Burns moved his animal emporium to 280 Front Street (the two-story building pictured here in 1936) around 1868. It was here, under the Brooklyn Bridge, that he began and established his wholesale animal-trade business.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

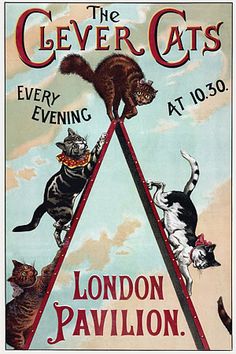

By the early 1870s, Donald Burns had become very well established as the go-to animal dealer for circuses, museums, menageries, and organ grinders (who purchased monkeys). In addition to the large place on Front Street, Donald also operated out of 115 Roosevelt Street, where he also lived for some time. During these early years, Donald also exhibited at a seasonal menagerie at Bergen Beach in Coney Island and traveled with P.T. Barnum’s circus, Joe Pentland’s (Pendleton) circus, and Andrew Haight’s Great Eastern Circus.

Although he specialized in birds and snakes, it was not uncommon for Donald Burns to serve as the middle-man in deals involving much larger animals, including gorillas, elephants, panthers, tigers, and more. One of his oddest deals, however, involved an Amazonian manatee that he named Rosy (perhaps for Roosevelt Street).

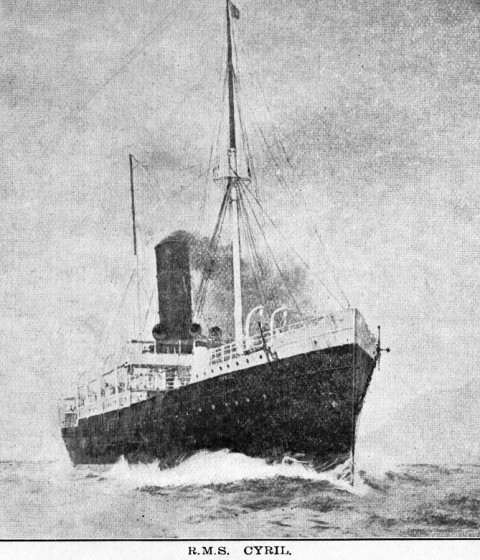

Rosy was only six months old and five feet long when she arrived at 115 Roosevelt Street in August 1891. Taken from the Amazon River Basin of northern South America, she came to America by way of Captain Robert Oliphant of the Booth Line Royal Mail Steamer Cyril. The long journey across the sea was arduous, as it was necessary for the crew to constantly fill her tank with the fresh water she needed to stay alive.

Rosy the manatee sailed from the Amazon River to New York City onboard the RMS Cyril. This ship was sunk in a collision with the Anselm 2, another Booth ship, on the Amazon River in 1905, while hauling rubber from Brazil to England.

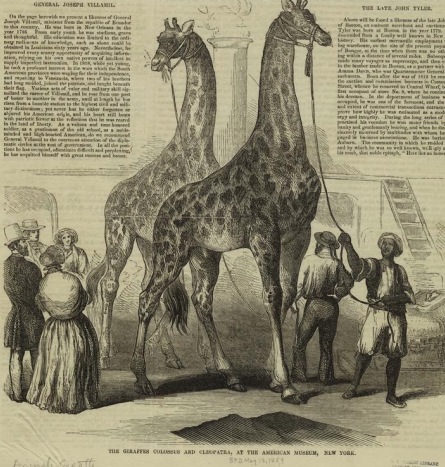

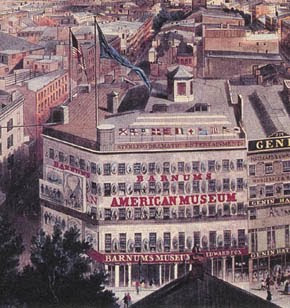

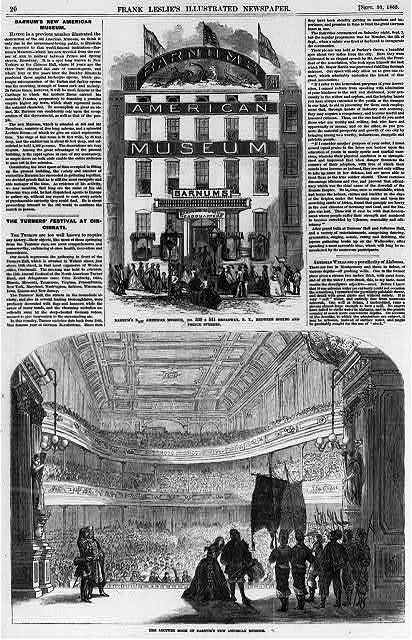

Rosy had been purchased by another dealer named John Robinson, and was scheduled to go on exhibit in one of the city’s dime museums — perhaps P.T. Barnum’s American Museum on Broadway. As she awaited her transfer, Rosy was temporarily housed in a large tank at Donald Burns’ animal emporium, which, at the time, was also serving as a temporary home for 11 wolves that were starring in a play at the Globe Dime Museum (one of which escaped on August 25 of that year.)

90 Royal Swans-a-Swimming

One year after Rosy’s arrival, Donald Burns received about 90 swans from Hollywood – the Hollywood Station on the New York and Long Branch Railroad in New Jersey, that is. The swans had all belonged to the late John Hoey, the former director of the Adams Express Company who developed The Hollywood Hotel and Cottages on Cedar Avenue in Long Branch, New Jersey in the 1880s. (President Chester A. Arthur stayed in one of Hoey’s cottages – more like mansions — in the summer of 1882.) You really should see his enormous ocean-front estate, “Hollywood,” and his elaborate gardens on the Historic Long Branch website – just search “Hoey.”

The flock consisted of about 90 swans of different varieties and of all ages, from nearly 100 years old to cygnets. Some of the swans had the Queen’s mark (five long ovals pointed at each end), which had been placed on their bills in England by royal order.

Several of the swans had been marked before Queen Victoria had ascended the throne in 1837. (The privilege of keeping a game of swans in England was at one time manifested by the grant of a mark, which was cut into the skin or beak with a sharp knife. The process of marking the birds was called swan-hopping or swan-upping, and was conducted with ceremony on the first Monday of August.)

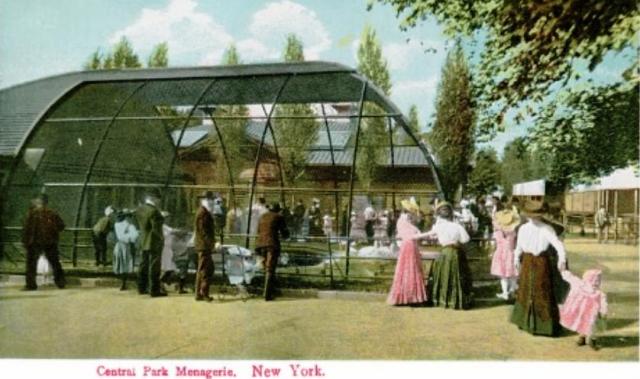

In this early 20th-century postcard, you can see a few swans inside the caged-in aviary at the Central Park Menagerie. Today, swans swim freely on the lake and many of the birds fly freely in the Central Park Zoo rain forest exhibit. A newer bird house, which was constructed in 1934 when the menagerie was refurbished to create the new zoo, is still standing today and now serves as a gift shop.

Upon their arrival at 115 Roosevelt Street on December 30, 1892, Donald Burns called on William A. Conklin, the Superintendent of the Central Park Menagerie, to see if he would be interested in taking the swans. Conklin said he’d have to make a formal application in writing to the Commissioners of Parks to have the swans admitted to the menagerie.

I cannot confirm whether these 90 British swans found a home at Central Park, but it would seem only natural, considering the fact that it was the gift of 12 swans from Hamburg, Germany, that started the menagerie at Central Park in 1860.

According to a letter dated May 9, 1860, from George K. Kunhardt, German Consulate, to R.M. Blatchford, president of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, the swans arrived in New York City on May 26, 1860, via the Hamburg America Line’s steamer Bavaria. As part of the gift, the Hamburg America Line had offered to take back the swan’s caretaker for free after he instructed the Commissioners of the Central Park on how to care for them.

Shortly after the 12 swans arrived from Hamburg, nine of them died. No poison was detected; it was believed that they died of cake, which had been fed to them by the children and women who came to watch them inside the enclosed aviary. The city of Hamburg immediately donated another 10 swans. Eventually, the swans were moved to the Central Park Lake.

Shortly after the 12 swans arrived from Hamburg, nine of them died. No poison was detected; it was believed that they died of cake, which had been fed to them by the children and women who came to watch them inside the enclosed aviary. The city of Hamburg immediately donated another 10 swans. Eventually, the swans were moved to the Central Park Lake.

The Last Hurrah on South Street

Sometime around 1895, Donald Burns and his assistant, Henry Kimm, moved one block east to 168 South Street, just north of Dover Street and directly under the ramp for the Brooklyn Bridge.

Donald Burns moved his animal emporium one last time to a large brick warehouse at 168 South Street, shown here (left) in this photo taken in 1927. Today this area is a vacant lot under the ramp for the Brooklyn Bridge.

Donald Burns moved his animal emporium one last time to a large brick warehouse at 168 South Street, shown here (left) in this photo taken in 1927. Today this area is a vacant lot under the ramp for the Brooklyn Bridge.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

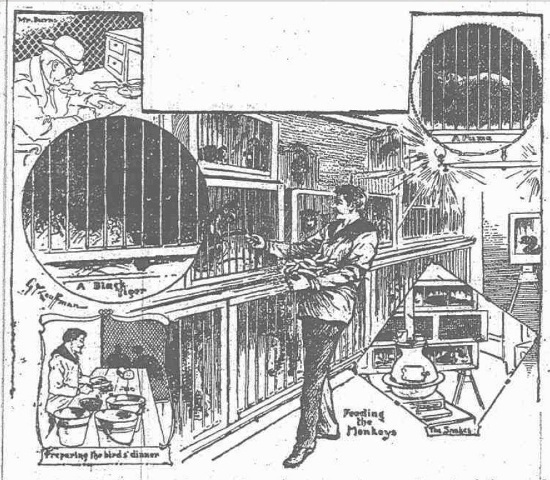

A few bird cages in the front windows were the only signs of what was inside the building. Inside, there was a small foyer separated from the rest of the building by iron bars (to protect the public in case any animals escaped their cages). One wall was lined with cages of parrots and other birds, and along the other walls were cages and boxes filled with all sorts of wild animals. On March 18, 1898, when this illustration below appeared in the Rome Semi-Weekly Citizen, a few elephants also occupied the back of the room.

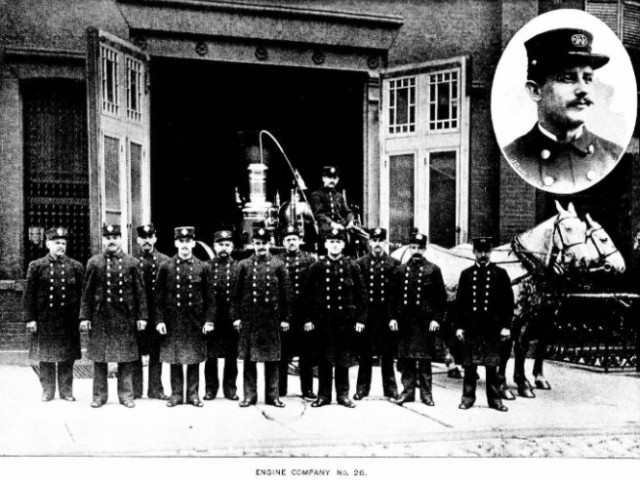

Reportedly, the animal business started to fail when a few of Donald’s circus clients went under. In 1900, city records reported him as being delinquent for failing to pay his annual rent of $916.63. Donald landed on his feet, however; he moved into a flat at 6 Dover Street, his wife gave birth to another son (perhaps Francis), and he took a job as the head keeper in charge of the aviary at the Central Park menagerie under the direction of John W. Smith. (His trapping skills came in handy in the job, as he often trapped birds on Fifth Avenue to replenish the aviary.)

In his later years, Donald Burns lived in an apartment in a brick tenement at

90 Roosevelt Street, seen here (far left). This photo was taken around 1930 to document the gentrification process that eventually obliterated the entire neighborhood to pave way for the New York City Housing Authority’s Alfred E. Smith Houses. New York Public Library Digital Collections

On December 14, 1915, at the age of 75, Donald Burns was placed in the New York City Home for the Aged and Infirm, Manhattan Division, on Blackwell’s Island. According to his admission papers, he was in poor physical condition and unable to work. His wife, Johanna, was also residing at the home on Blackwell’s Island.