This is one of my longer stories — which is why it took me so long to post — but it’s chock full of New York City and Murray Hill history.

In March 1908, NYPD Detective Henry G. Firneisen purchased six Belgian sheepdogs from the Ghent Kennels in Belgium. One dog reportedly died enroute to America and was replaced with an Airedale terrier. AKC Gazette, 1928.

In July 2013, I wrote about the police dogs of Parkville Brooklyn, who came to America in 1907 and were the first canine police squad in New York City. Those dogs were so successful in stopping crime in the rural areas of Brooklyn that the city decided to get a few more in 1908.

A jewel heist involving a New York socialite and a good butler gone bad created the perfect opportunity to add a few more K9 cops to the New York City police force.

The $8,000 Jewel Theft

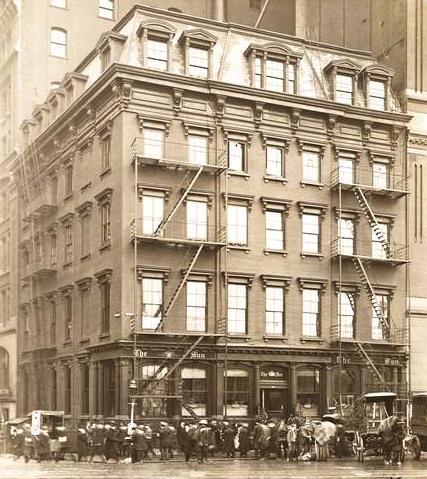

On Sunday, March 8, 1908, David Percy Morgan sent a messenger boy to the police headquarters building at 300 Mulberry Street to report that $8,000 worth of diamonds and jewelry, including heirlooms, had been stolen from an open safe belonging to his mother, Carolyn Fellowes Morgan.

Mrs. Morgan was the widow of David Pierce Morgan, a Wall Street banker and distant relative of J.P Morgan (both men were descendants of brothers Miles and James Morgan, who came to America in 1636). She had married David Morgan in 1858 at the age of 26 and had seven children: Caroline, William, Clara, David, Alice, Lewis, and James.

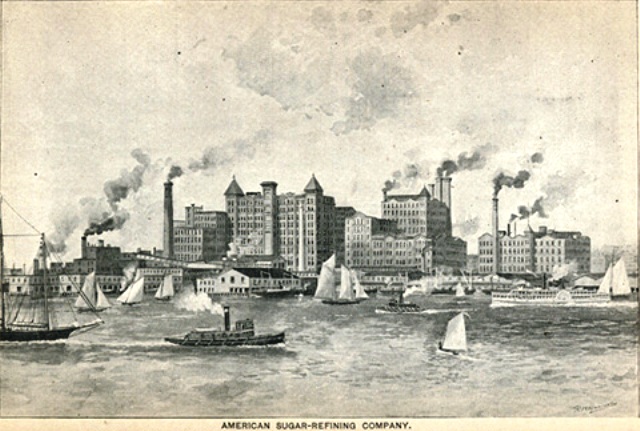

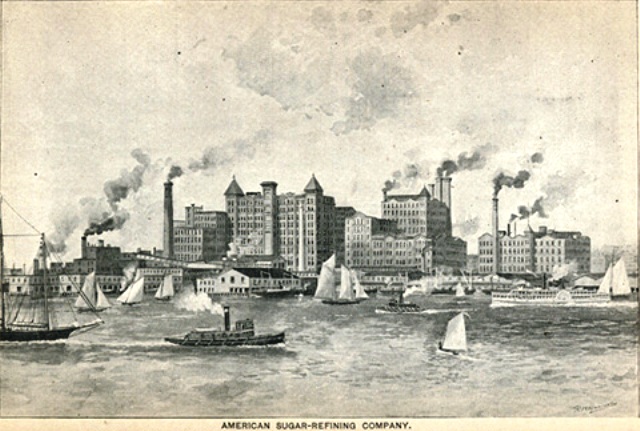

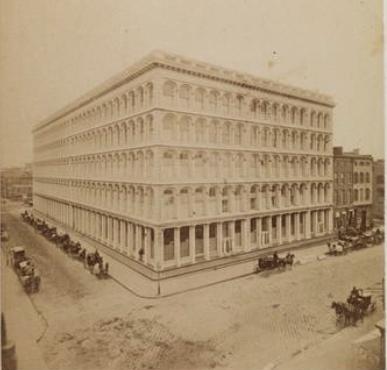

Before losing his wife and his fortune, David P. Morgan was an assistant treasurer for the American Sugar Refining Company – aka, the Sugar Trust and Domino Sugar. Incorporated in New Jersey in 1891, the ASR was the largest American business unit in the sugar refining industry in the early 1900s. It operated one of the world’s largest sugar refineries in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, pictured here in 1893.

At the time of the theft, David P. Morgan was living with his mother in her four-story-with-basement brownstone at 70 Park Avenue in the Murray Hill section of Manhattan (she also had a home in Washington, D.C.).

A former assistant treasurer for the American Sugar Refining Company, David had recently been divorced from his wife, Edith Parsons. Two months before the burglary, he also lost his entire fortune in the stock market.

In this circa 1917 photo, Nos. 68 and 70 Park Avenue are the brownstones in the center (mansard roofs), at the corner of Park and 38th Street. The first floor of No. 68 — the Gould residence — appears to be boarded up. Museum of the City of New York Collections

Mrs. Morgan occupied a room on the second floor of the townhouse, where she kept her jewels in a small safe. Sometime around 6 p.m. that day, she discovered that several items, including a Louis XVI diamond tiara, diamond collaret, diamond brooch, three gold bangles, diamond heart-shaped locket, pearl necklace, diamond earrings, diamond sunburst, and several less valuable pieces were missing from the safe.

David tried to call the police by phone, but the telephone wires had been disconnected. So he called for a messenger boy to deliver a note to police.

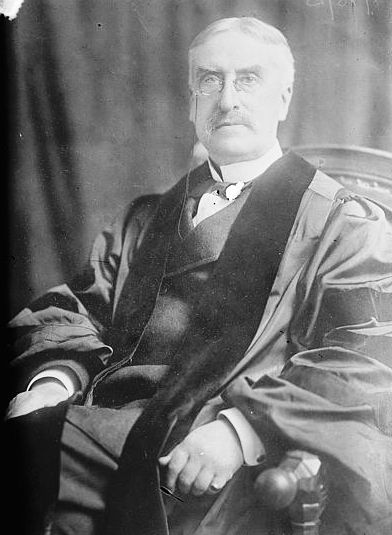

Detectives William Browne and Henry G. Firneisen responded to the residence.

The Butler Did It

How many times do you get to say “the butler did it” and actually mean it?

When the detectives arrived, they concluded that it was an inside job. They took a census of the servants and discovered that the second butler, Claude J. Heritier, was missing in action.

The Morgans told police that they had last seen him about 4 p.m. on the second floor. They also said Heritier had been very faithful since joining the family in November 1906, and that he had previously worked at the Whippany Club in Morristown, N.J.

On June 15, 1904, Henry Firneisen’s wife, Emma Christina, daughter Marie Theresa, and sons Henry and William, were aboard the General Slocum when it caught fire and sank in the East River, killing an estimated 1,021 of the 1,342 people on board. The Firneisens, who lived at 40 East Seventh Street, were able to tread water until they were rescued by Engineer Patrick J. Lynch of Engine Co. 60. Henry Firneisen presented Lynch with an inscribed gold chain and watch. Lynch also received the Congressional Medal of Honor for saving 45 lives that day.

While searching the home for clues, detectives Browne and Firneisen discovered a checkerboard game with Heretier’s name and the following address scribbled on the back of the board: 70 Portsmouth Square, London. They immediately cabled Heretier’s description and address to Scotland Yard in London.

Now it turns out that Claude Heritier (alias Lester Graham) had an accomplice by the name of William O’ Connell (aka William Wilson), a former ship steward. Following the burglary, the two men occupied a room that they rented just two blocks from the Morgan residence. For two weeks, they hid out there and took turns watching the detectives enter and leave the Morgan house.

During this time, the men sold a valuable pair of earrings in a saloon. They also discovered that two of the necklaces were imitation pearls.

The jewel thieves tossed some of Mrs. Morgan’s costume jewelry from the old bridge that connected Madison Avenue in Manhattan to 138th Street in the Bronx. This bridge was designed by architect Alfred Pancoast Boller and opened in 1884 at a cost of $509,106. It was later replaced by the much larger Madison Avenue Bridge, a four-lane swing bridge that cost $1.1 million when it opened in 1910.

Cash in hand, they headed up to the Bronx and tossed the costume jewelry into the Harlem River from the bridge at 138th Street. Then they made their way to Philadelphia, where they boarded the Red Star Line steamer Marquette for Antwerp, Belgium. In Antwerp, Heritier sold about nine loose diamonds worth about $300 to a dealer.

The Fugitives Are Captured

On April 20, Heritier was arrested in London by Scotland Yard and remanded to the Marylebone Police Court. He was carrying 16 small diamonds valued at $400 when he was captured, but he couldn’t give police a good reason for having them.

A week later, on April 27, Scotland Yard recovered two necklaces in Heritier’s lodgings. He confessed to the crime and also named William O’Connell, who had been arrested in Liverpool on April 25 when he was found with 14 loose diamonds in his pockets. The two men were held in London to await extradition papers from New York.

The sheepdogs were thoroughly trained in catching vagrants and escaping marauders at the kennels in Ghent. It was Firneisen’s job to teach the dogs all the commands in English.

Following the arrests, detectives Firneisen and Browne – who had both traveled to London at the end of May to make extradition arrangements – separated to do some other police work in Europe. While Browne went to Paris, Firneisen set out for Antwerp to find the loose diamonds — and a few good police sheepdogs from the famous kennels at Ghent.

As Firneisen told the New York press:

“The dogs I intend to purchase are of the same breed and in fact come from the same kennels as those that have proved so valuable to the Belgium police, who were the first to train dogs to detect crime. Some of them are already trained, but I shall spend the time occupied in the voyage to New York two weeks hence in getting acquainted with them and teaching them English.”

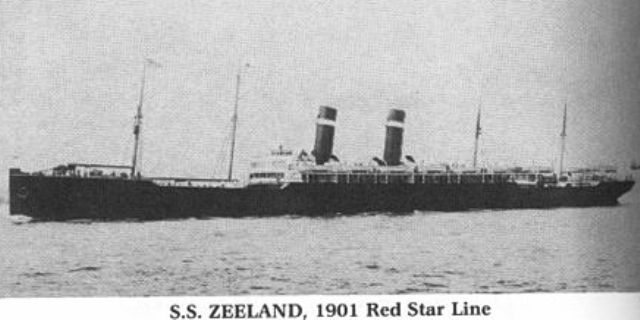

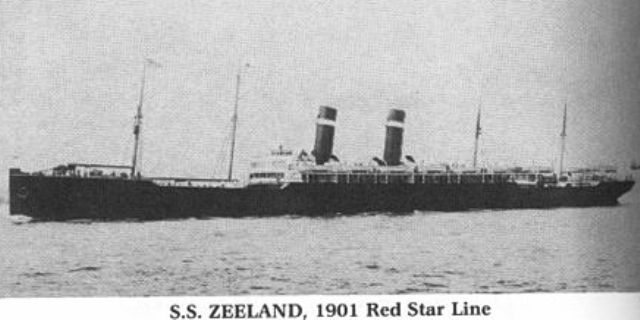

On June 7, Detective Firneisen, Detective Browne, Claude Heritier, William O’Connell, and six sheepdogs boarded the Red Star Line SS Zeeland in Antwerp. A week later, when the ship was within 20 miles of the Sandy Hook lightship in the Ambrose Channel, many passengers were startled to see Detective Browne put handcuffs on Claude and William. Apparently, the men had been allow to mingle freely with the passengers on the trip over (I wonder if they picked anyone’s pockets?).

The detectives returned to New York City aboard the Red Star Line SS Zeeland on June 15, 1908, with two fugitives and five police dogs in tow (one dog died in transit).

The Morgan Home at 70 Park Avenue

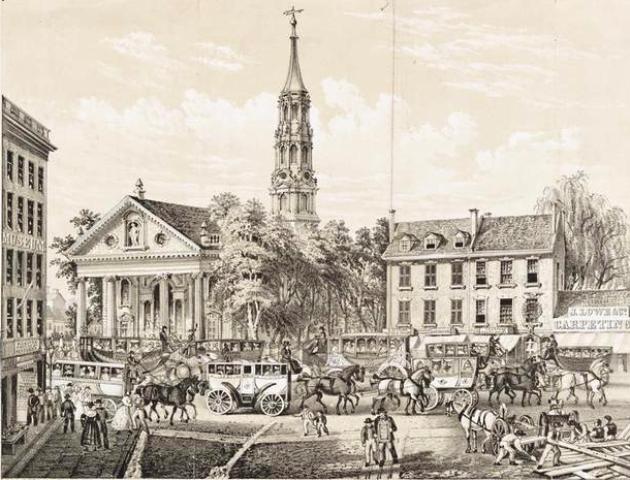

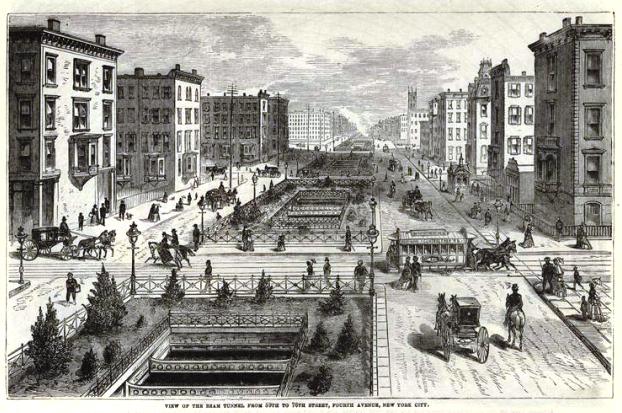

The Morgan townhouse on the northwest corner of Park Avenue and 38th Street was in the neighborhood known as Murray Hill, which takes its name from the eighteenth-century country estate and farm of Quaker shipping merchant Robert Murray.

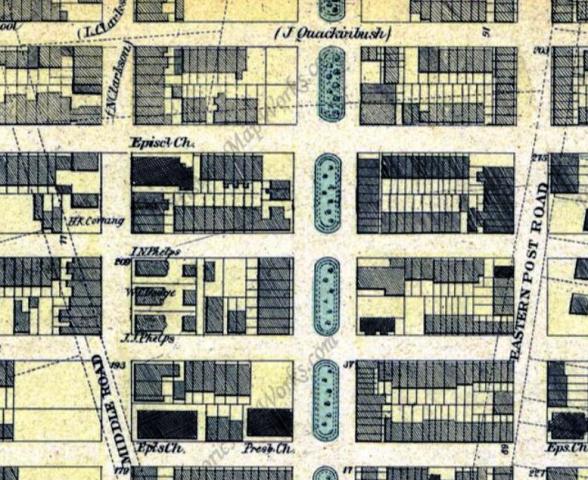

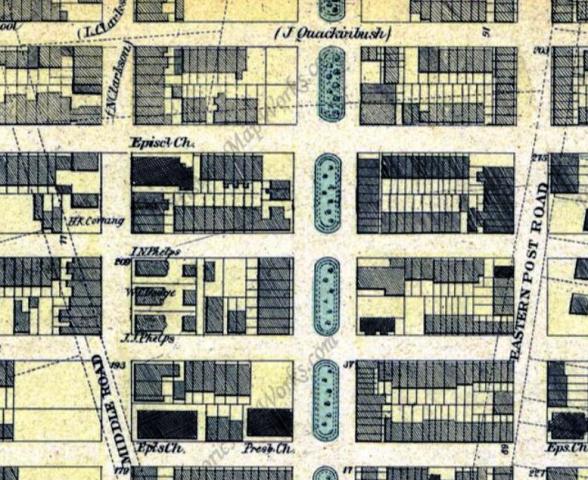

To be exact, it was located on what was the northernmost boundary of Murray’s 29-acre wedge-shaped parcel, which extended from about today’s 33rd Street to 38th Street between the old Eastern Post Road (aka Boston Post Road) near present-day Lexington Avenue and the old Middle Road (near today’s Madison Avenue).

In this 1867 Matthew Dripps map, you can see the old boundary lines of the Murray farm between Middle Road and Eastern Post Road. The three Phelps family mansions, erected in the 1850s on the east side of Madison Avenue between 36th and 37th streets, are visible to the left.

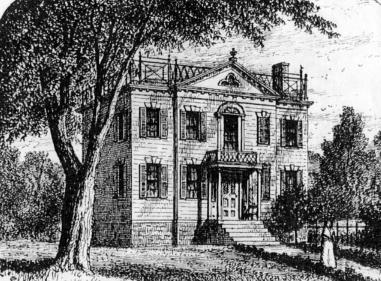

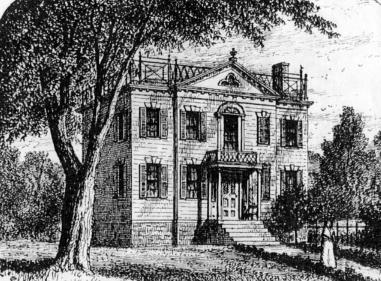

The Murray farm was located on a high point of Manhattan that was once wilderness and called Inclenbergh in the 1700s. Robert and his wife, Mary Lindley Murray, leased the common lands from the city in the 1750s (the city leased land to meet the expenses of building the new City Hall on Wall Street), and in 1760 they erected a mansion that they named Belmont on the crest of the hill at what is now the intersection of Park Avenue and East 36th – 37th Street.

Surrounded by wide lawns and extensive gardens, and approached by a tree-lined avenue from the Eastern Post Road, the Murray’s Colonial-style home had a magnificent view of Kips Bay and the East River. When the New York City street grid was superimposed over the Murray farm in 1811, the house was located within Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue). However, the street grid remained solely on paper, and the land remained a farm until the house burned down in 1834.

In addition to the large house, the property featured two barns, a coach house, a large garden, and meadows for cultivating hay. The Murrays also owned a large cornfield that was reportedly located on the site of today’s Grand Central Station. During the Revolutionary War, British soldiers marched through these fields.

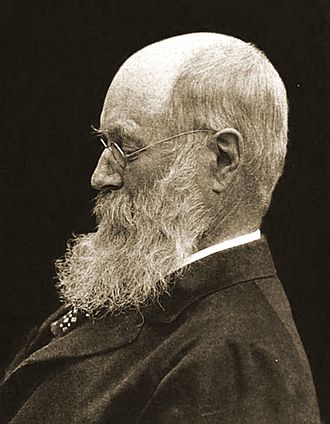

Following Robert Murray’s death in 1786, the farm went to his daughter Susannah, the wife of Captain Gilbert Colden Willett. Willett had a business with Robert’s brother, John Murray, and when that failed in 1800, Susannah and Gilbert passed the lease to John. John Murray eventually purchased the property from the city for $62,000 in 1806.

After John Murray’s death in 1808, his children Mary and Hannah Lindley Murray, Susan Ogden (wife of William Ogden), and John R. Murray occupied the house. Several attempts were made to rent or sell the property in 1812 and 1813, but I do not know the outcome of these early efforts.

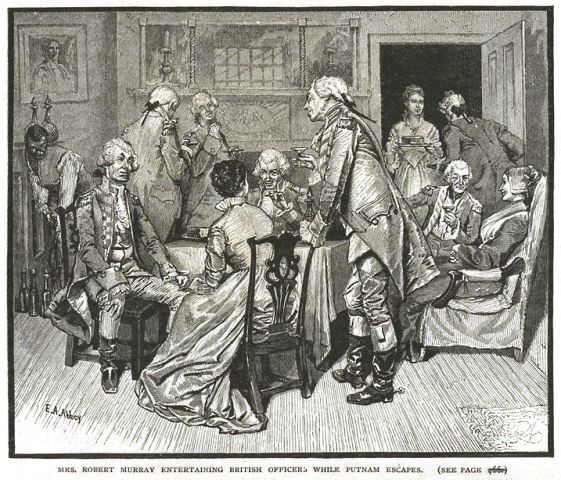

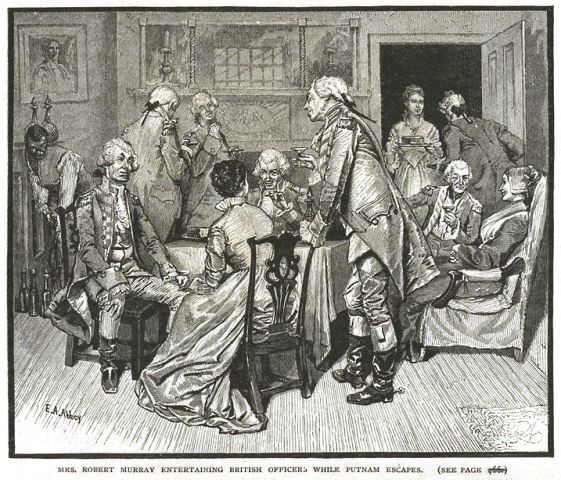

George Washington and British Commander William Howe reportedly spent some time at the Murray home during the Revolutionary War in September 1776. In fact, the Murrays played a key role in the war by hosting a “party” at their home on September 15 of that year, in which they served good food and wine to the British soldiers in order to distract them while the New York troops under the command of Major General Israel Putnam were making their escape up to Harlem Heights. NYPL Digital Collections

In 1835, the Murray heirs imposed a series of restrictive covenants on some land that they sold to the Ministers, Elders, and Deacons of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of the City of New York on the north side of East 38th Street. The church had previously purchased the northern half of the block from the James Quackinbush estate, and it needed the Murrays’ land in order to divide the block into standard 25 x lOO foot building lots. No. 70 Park Avenue was erected on one of these lots.

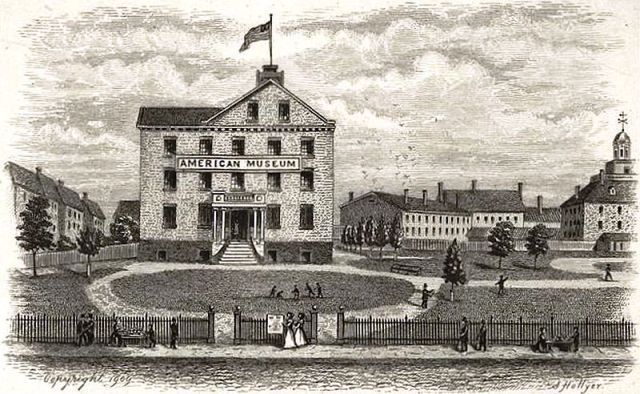

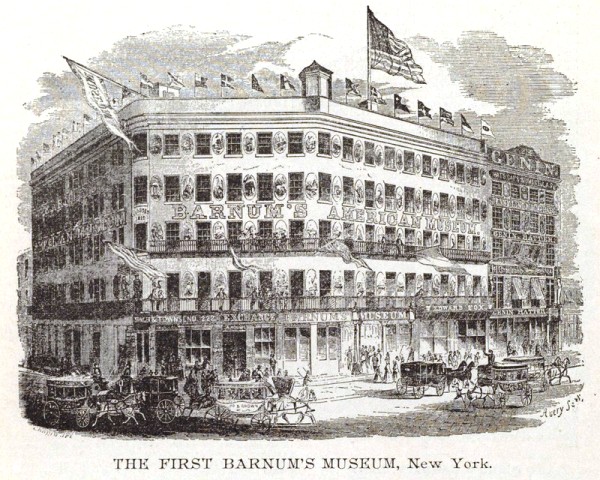

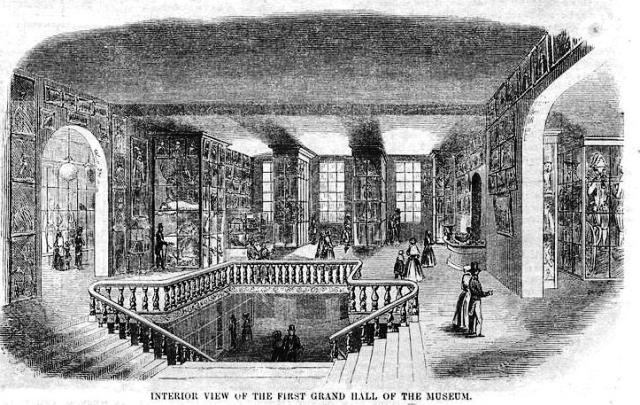

The covenants restricted development to “brick or stone dwelling houses of at least three stories.” Exceptions could be made for private stables, carriage houses, and churches, but such establishments as smith shops, breweries, and places for the exhibition of wild animals were expressly forbidden.

Although the Murray heirs started to sell their farm land in the 1830s, the development of Murray Hill did not begin in earnest until the 1850s. Here are a few of the first Murray Hill stone houses constructed on Lexington and 37th Street, circa 1859. Museum of the City of New York Collections

On June 11, 1835, James Bleecker & Sons auctioned off the Murray Hill Estate – about 400 lots in all. Most of the buyers were lawyers and businessmen who could afford to hold the property for a few years as an investment until the residential district expanded northward into Murray Hill.

Development first took off in the early 1850s at the western edge of the former farm, when three members of the Phelps family erected mansions on Madison Avenue between East 36th and 37th streets. Thirty-three feet wide and seventy-three feet deep, the houses were “furnished in elegant and luxurious style” and featured elaborate gardens and private stables.

In 1931, the Union League Club’s fourth clubhouse was erected on land owned by J.P. Morgan — and once occupied by the Robert Morgan farm and homestead. Museum of the City of New York Collections

The northern-most Phelps mansion was later home to J.P. Morgan, Jr., and today is part of the Morgan Library & Museum. In 1926, J.P. Morgan also purchased the property upon which the old Murray homestead once stood. Four townhouses on the property were torn down and replaced with the elaborate clubhouse for the Union League Club, of which he was a member.

As for 70 Park Avenue, the earliest record goes back to 1886, when the townhouse was occupied by John T. Farish, a Virginian who made his wealth in tobacco. The Farish estate sold it to Dr. John C. Barron in 1895, who in turn sold it to Oliver Harriman in 1901 for $31,500.

Carolyn F. Morgan purchased 70 Park Avenue in November 1905 and installed an elevator in 1909. In 1912, two years before her death, her son William Fellowes Morgan moved into the home.

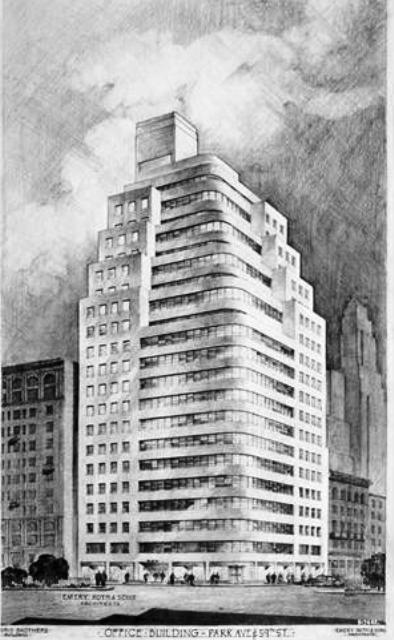

In 1925, Nos. 70 and 68 were acquired from William Morgan and the late Charles A. Gould and demolished to make room for a 15-story apartment hotel. Today this is a boutique Kimpton Hotel called 70 Park Avenue. It happens to be a pet-friendly hotel that accepts “any number of pets without size or weight restrictions and for no extra charge or deposit.” You just gotta love that!

In this circa 1926 photo, the new 15-story apartment hotel at 68-70 Park Avenue is visible at left. Museum of the City of New York Collections

And speaking of dogs, on September 6, 1908, The New York Times reported on the new police dogs’ progress. All of the dogs were in active service in Flatbush, and according to Fourth Deputy Police Commissioner Arthur Woods, the dogs had made good.

“Why, let me tell you something,” Woods told a reporter. “Burglars are so rare in Flatbush now that we have to put fake burglars on the job to keep the dogs in practice. Why, the burglars fear those police dogs a lot more than they fear the cops.”

The dogs continued to make the headlines in Flatbush and Parkville, Brooklyn, until 1951, when the caretaker of the dogs’ kennel at 2801 Brighton Third Street (present-day mounted police Troop E stable) retired and the canine unit was dissolved on the “grounds of obsoleteness.”

![[Park Avenue from 55th to 59th Street.] Upper East Side under development.](https://hatchingcatnyc.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/parkave55th-1.jpg)