Although the story of Yankee Stone is not very interesting on its own, Kingsley Swan and the other people and places surrounding the dog and his death in Fort Greene are quite fascinating, and provide a unique look at high society Brooklyn during the Gilded Age.

“The good citizens who reside in the aristocratic Clinton Avenue section were startled last night by hearing a pistol shot ring out from the yard of Kingsley Swan. Windows were thrown open, heads appeared and neighbors came running to 180 Clinton Avenue, the home of Mr. Swan, to find out what happened.”

So begins the story printed in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on December 3, 1908.

Kingsley Swan, the Entitled Heir of a Brooklyn Legend

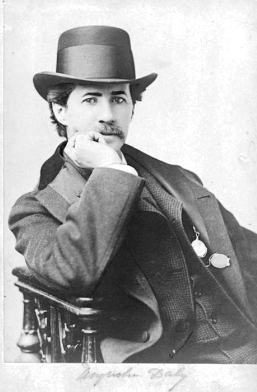

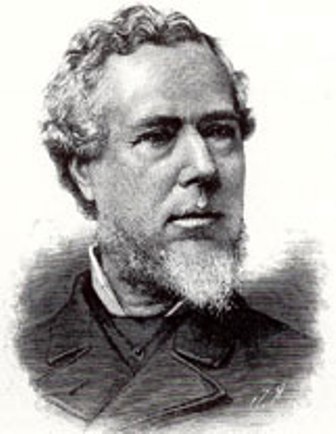

Born in Brooklyn on May 12, 1884, Kingsley Swan was the son of Wall Street broker Samuel Swan and Mary S. Kingsley. Although his father was fairly well-to-do, Kingsley inherited his wealth – and his place in high society – from his grandfather, William Charles Kingsley.

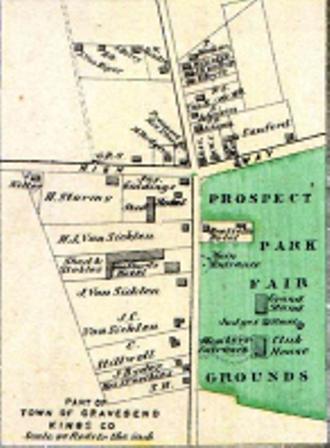

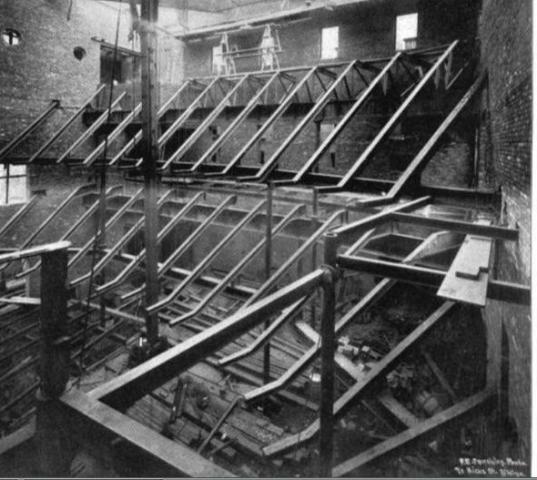

William Kingsley was a Brooklyn contractor and builder whose company, Kingsley and Keeney, built Prospect Park. He was also one of the owners of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and, drum roll, please, the principal shareholder of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge Company, the company organized in 1867 to build the Brooklyn Bridge.

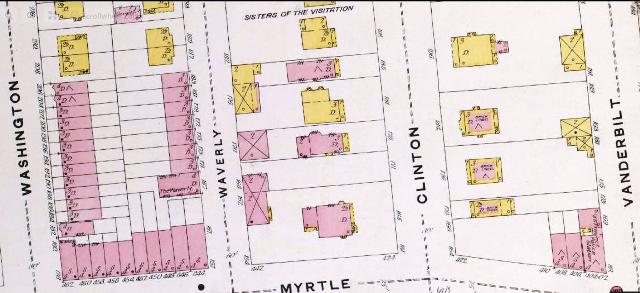

When he was about 10 years old, Kingsley’s mother died, and his father headed west. Kingsley and his younger brother Halstead moved in with their grandmother at 176 Washington Park, near Fort Greene Park (prior to 1897, Fort Greene Park was called Washington Park.)

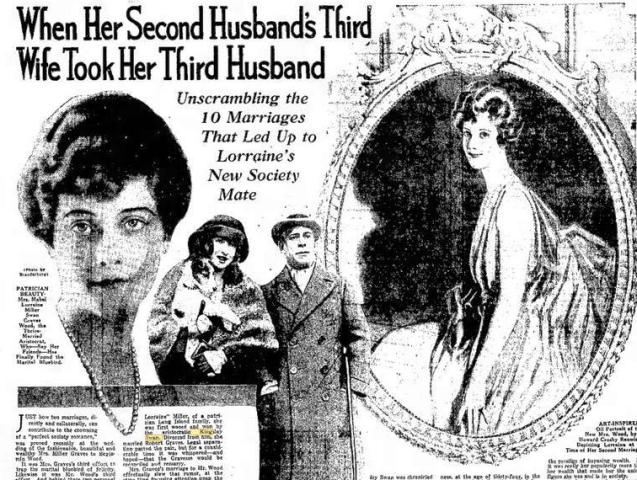

Following his schooling at the Polytechnic Preparatory School, the Brooklyn Latin School, and Lawrenceville Academy in New Jersey, Kingsley took a job at the Brooklyn Eagle. On October 1, 1908, he married 19-year-old Park Slope socialite Mabel Lorraine Miller, the daughter of paper manufacturer Alvah Miller and Phoebe A. Miller.

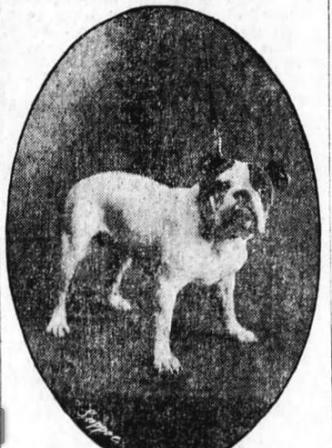

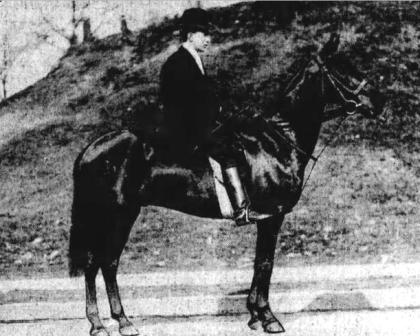

Having inherited great wealth from his grandfather, Kingsley spent most of his time exhibiting horses, racing automobiles, and taking part in other sporting fads and social clubs for millionaires. In 1908, when he was just 24 years old, he was also one of the most successful bulldog fanciers in Brooklyn.

The Killing of Yankee Stone

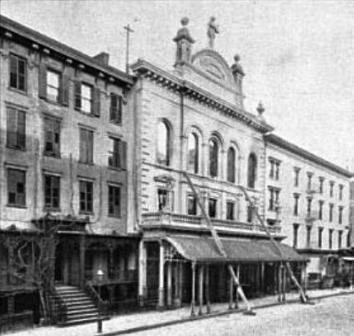

Two of Kingsley’s most famous champion bulldogs were Linda and Yankee Stone. In 1908, these dogs, as well as two other bulldogs and Mrs. Swan’s pet toy fox terrier, lived with the couple in a four-story brownstone at 180 Clinton Avenue in Fort Greene.

Sometime just after midnight on December 2, 1908, the little terrier made the mistake of leaving his bed upstairs and entering the kitchen, which was Yankee Stone’s indoor territory. The bulldog growled and jumped on the terrier’s back, sinking his teeth into the terrier’s neck. Within moments, the other bulldogs joined in the fight.

The first to arrive on the scene was Hugh Bracken, Kingsley’s long-time servant and coachman who had been with the family since Kingsley’s childhood. He tried to separate the dogs, which encouraged Yankee to go after him while the little dog ran for cover. Yankee was biting Hugh when Kingsley came to the rescue and pulled Yankee Stone away.

While the other dogs quickly calmed down, Yankee continued to growl. Kingsley tossed him in the back yard and went for his pistol.

Clinton Avenue – Brooklyn’s Gold Coast

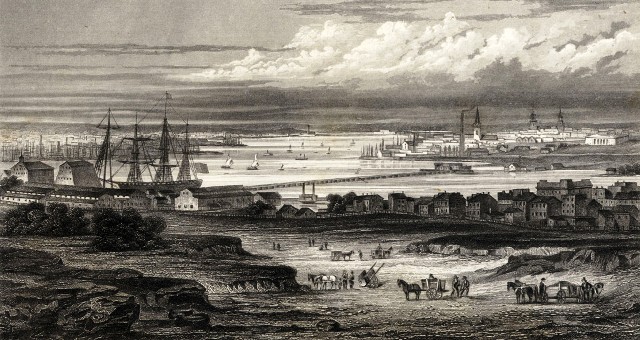

Clinton Avenue was named for New York State Governor DeWitt Clinton. Clinton was the chief supporter of the Erie Canal, which established New York and Brooklyn as America’s leading harbors and commercial centers.

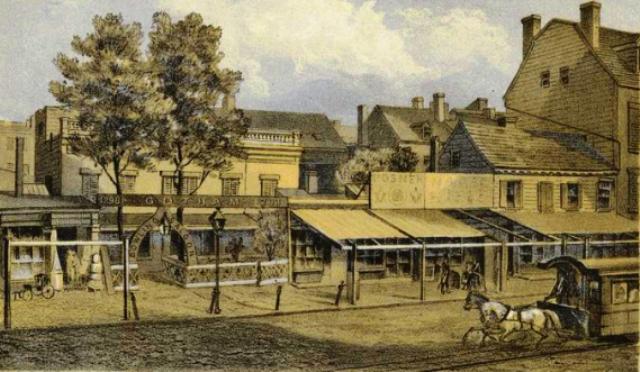

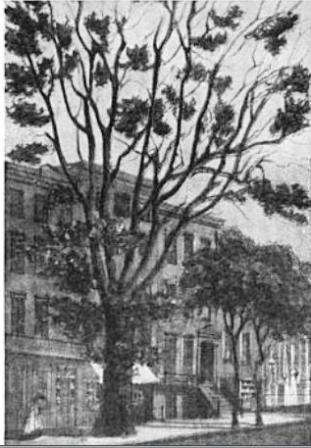

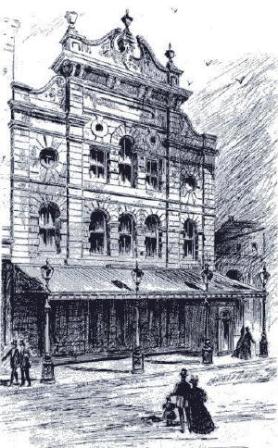

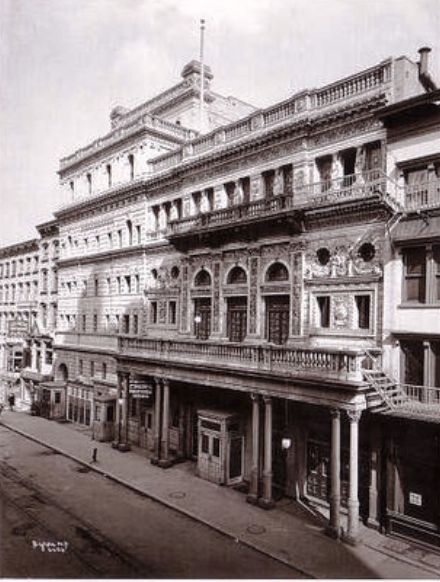

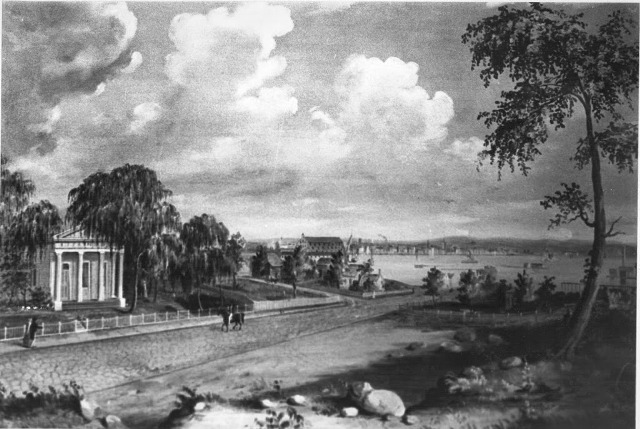

Located on one of the highest points in Brooklyn, the broad tree-lined street had attracted affluent people who erected large suburban villas in the 1830s, and, later, in the 1860s and 1870s, oil executives and financiers who built impressive brick and limestone mansions.

Although most of the mansions had already been replaced by row houses in 1908, and many of the old-money folks had moved or passed on, it’s still safe to say that the new-money aristocrats on the hill never expected to hear the sound of gun shots on their quiet street.

The Ryersons, Vanderbilts, and Spaders

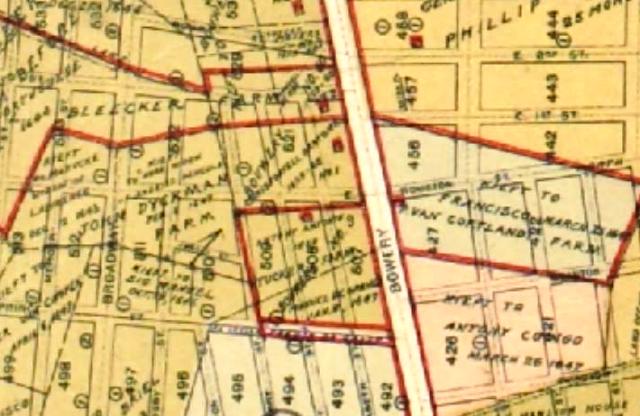

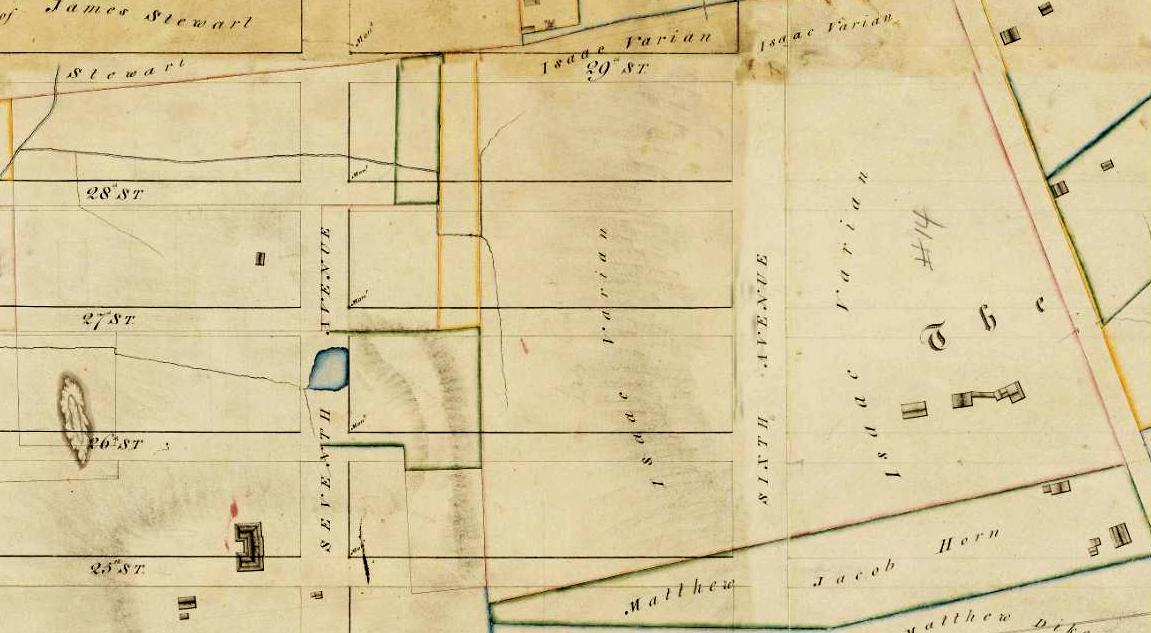

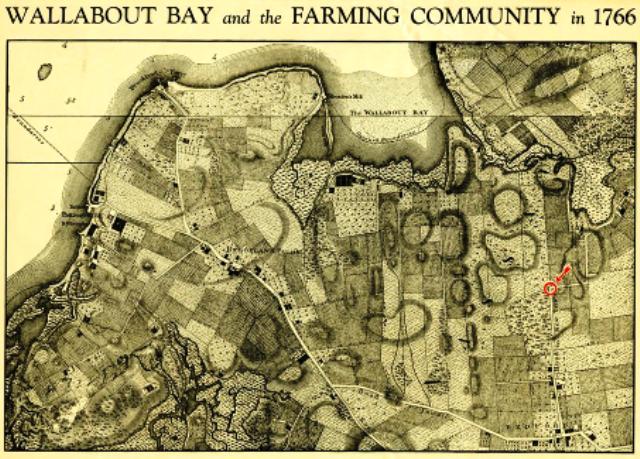

The Clinton Hill history begins around 1637, when Joris Jansen Rapalje, a Walloon tavern keeper who lived on Pearl Street in Manhattan, purchased 167 morgens (335 acres) of lowland and mud flats on an inlet in the Wallabout Bay (then called Waal-bogt Bay). Joris and his wife Catalina Trico moved to the farm in the 1650s, and were later joined by their daughter Sara and her husband, Hans Hansen Bergen. The brothers Pieter and Jan Monfort also established a large farm there.

A good portion of this farmland was later acquired by Marten Ryerse (Ryerson), who had married the Rapaljes’ daughter Annetje around 1645. Over the next 100 years, the land was passed down to generations of Ryersons, Vanderbilts, and a few other families.

Following the American Revolutionary War, an army private named William Spader of Somerset County, New Jersey, moved to Brooklyn. He married Annie Vanderbilt, the daughter of Jeremiah Vanderbilt and Antje Ryerson, and established a farm near the Vanderbilt property on the Wallabout Turnpike. When the Spaders later later moved to Bedford, their sons John L. and Jeremiah V. stayed behind.

In February 1821, a year after Jeremiah Vanderbilt died, all his land comprising the old Monfort farm patent was put up for auction. Jeremiah Vanderbilt Spader and his wife, Maria Bergen, bought 38 acres that extended from today’s Flushing Avenue to Willoughby Avenue between Vanderbilt and Clermont.

The widow Antje Vanderbilt purchased 72 adjacent acres extending from Wallabout Bay to the Brooklyn and Jamaica Turnpike Road (Fulton Street) between present-day Vanderbilt and Waverly avenues. She later sold this land to her grandson John Spader.

In 1833, at the peak of a Brooklyn development boom, John Spader sold his farm for $62,593.27 to George Washington Pine, a partner in Pine & Van Antwerp, a New York City auction house. The development was laid out quite generously, with individual lots measuring 100 x 246 feet.

Clinton Avenue, which ran down the center of the development from the Wallabout Bay to the Brooklyn and Jamaica Turnpike Road, was developed as an 80-foot-wide boulevard with a double row of trees.

Meanwhile, Jeremiah Spader held out, leaving most of his property undeveloped so he could continue farming. He died in 1838, but his wife stayed on until she sold the property at auction on March 27, 1849. Jeremiah’s land was divided into 100 standard city lots, most measuring 25 by 100 feet.

The War of the Swans

Other than the incident with Yankee Stone, the first few months of Kingsley and Lorraine’s marriage seemed typical for newlyweds in Brooklyn high society. The couple often appeared in the newspaper society pages, and their masquerade ball at the Pouch Gallery in December 1908 was a big hit with the socialites on Clinton Hill.

Sometime in 1912, Lorraine gave birth to a boy, whom the couple named Kingsley Swan Jr. Dad paid little attention to his son, however, as he was too busy gallivanting with his friends at horse and dog shows, spending time at his Croton Lake Kennels in Katonah, New York, and racing his fancy automobiles.

At her husband’s suggestion, Lorraine moved back home with her parents and he returned to his grandmother’s estate. Kingsley came to visit his wife and son one time in 1913, but he never returned.

In March 1914, Lorraine was granted a divorce in Reno, Nevada, on grounds of desertion, non-support and cruelty. She told the judge that her husband had failed to support her and told her that reconciliation was impossible. He simply could not support her and the baby and keep up his social clubs, automobiles, and horses. Society first learned of the divorce when a dispatch appeared in the newspaper stating that Lorraine had fallen from a horse in a Nevada “colony of misfit mates.”

Immediately after the divorce, Lorraine married 57-year-old Robert Graves, the son of the wallpaper manufacturer. She and Robert lived in Huntington, Long Island, and also had an apartment at 67 Park Avenue. They had had a son, Richard Barbey, and a daughter, Lorraine.

The Graves were divorced in Paris in 1922. In December 1928, Lorraine moved back home from Paris to give it another try – this time with Benjamin Wood, the son of Fernando Wood, three-time Mayor of New York City. They lived together at 4 East 72nd Street in Manhattan until Benjamin’s death at home in March 1934. (Three years earlier, in 1931, Graves had committed suicide in his apartment on Park Avenue.)

Less than a year later, on January 3, 1934, Lorraine made the headlines one more time when she eloped and married Kiliaen Van Rensselaer — a direct descendent of the Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, who came to America in the 1600s and was the first patroon of Van Rensselaerwyck. The couple lived on and off again (they often separated) in Old Westbury, Long Island, and at their summer home at Lloyd Harbor in Huntington, Long Island. Kiliaen died at their home, Post Cottage, on Post Road in Old Westbury in August 1949.

On March 7, 1950, the lovely Lorraine married Lieutenant Colonel Henry Aldrich Granary in her home at 563 Park Avenue. (In case you lost track, this is husband #5.) They also lived in Old Westbury, which is where she died on July 26, 1953, at the age of 64. She was survived by her daughter, Mrs. Oliver R. Grace of Manhattan, and her sons, Kingsley Swan Jr. of Lyme, Connecticut, and Richard Graves of Old Westbury.

What About Kingsley Swan?

Kingsley’s life after Lorraine was a lot less complicated. He married a woman named Julia Murray in 1916 and two years later he enlisted in the army. He served for a brief time at Camp Wadsworth and Camp Stuart, but he was discharged due to heart trouble. He died suddenly of heart disease on August 22, 1918, at the St. George Hotel in Brooklyn. He was just 34 years old.

Kingsley Swan left $10,000 to his brother, $21,000 to Hugh Bracken, $65,000 to Julia, and $27,000 to Kingsley Jr. He was buried in the Kingsley plot at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

And so ends the tale of Yankee Stone, Kingsley Swan, and Mable Lorraine Miller Swan Graves Wood Van Rensselaer Granary.