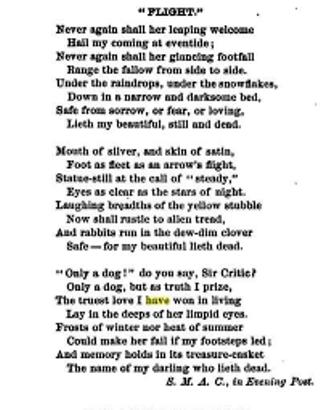

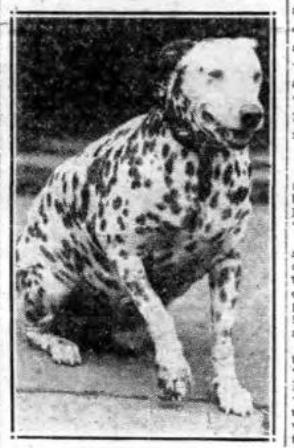

Only a dog do you say, Sir Critic?

Only a dog, but as truth I prize,

The truest love I have won in living

Lay in the deeps of her limpid eyes.

Frosts of winter nor heat of summer

Could make her fail if my footsteps led:

And memory holds in its treasure casket

The name of my darling who lieth dead.

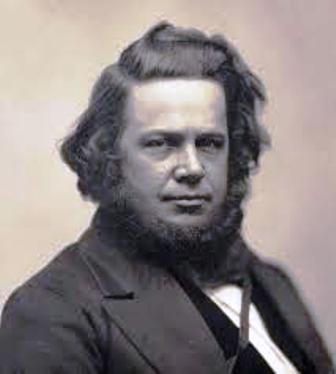

On the southwest corner of Battle Avenue and Hemlock Avenue in Brooklyn, just down from the Civil War Soldier’s Monument on Battle Hill in Green-Wood Cemetery, there is a circular plot of grass (lots 19967 and 19970) surrounded by a low wall of Quincy granite. In the center, there is a granite monument with a once-bronze bust of a long-haired man and the name “Howe” engraved in large letters.

In this plot are buried Elias Howe, Jr., his second wife, Rose Halladay Howe, and several other family members. One of the family members reportedly buried in this plot is Fannie, Mrs. Howe’s beloved pure-bred Pug.

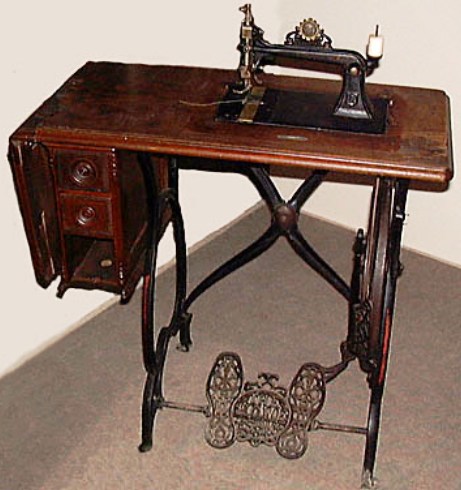

Fannie the Pug came into Rose Halladay Howe’s life about two years after her husband, Elias Howe Jr., passed away. Elias Howe Jr., as you may or may not recall from your grammar school history lessons, is credited with inventing the sewing machine (nope, it wasn’t Singer).

Actually, Thomas Frank developed the first sewing machine in 1790, but it wasn’t practical. Elias was granted a patent for the lockstitch (the basic stitch made by a sewing machine) in 1846. This patent expired in 1867, the same year Elias died of Bright’s disease (kidney disease) at the young age of 48.

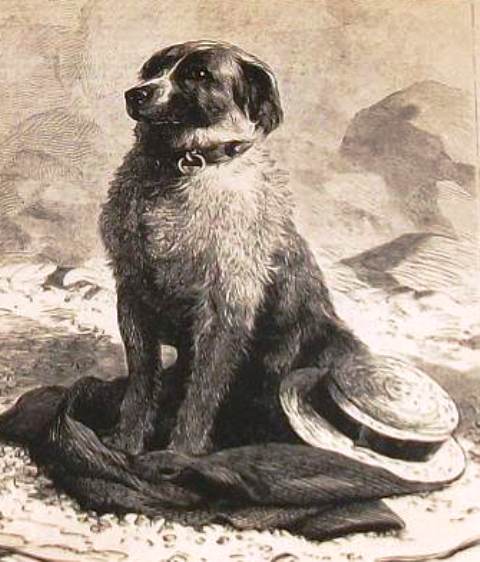

Although Fannie was only a dog, she was quite well known in New York City’s canine society. For twelve years, she lived with her mistress in a luxury brownstone at 330 Clinton Avenue in Brooklyn. Rose and Elias never had any children together (Elias had three children with his first wife, Elizabeth Jennings Ames), so Fannie was quite the pampered pooch.

When Fannie died on December 10, 1881, Rose Howe was inconsolable. According to an article published in 1889 in the Brooklyn Eagle, she insisted that the Pug was entitled to a funeral “such as never before was given a dumb animal in this country.”

Cards were immediately delivered announcing the funeral, and friends of Mrs. Howe came from all over New York and Brooklyn to her house bearing floral arrangements to honor only a dog. Some of the women also brought their dogs so they could also participate in mourning.

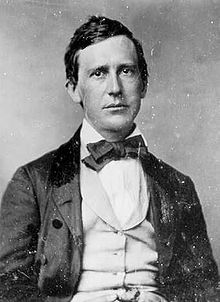

There was a quartet who sang many songs, including Stephen Foster’s “Old Dog Tray'” and Rose’s minister friend offered a funeral sermon. All the while, the body of Fannie reposed in a silver casket with a glass cover, completely draped with a gold embroidered white cloth, only her face exposed.

Shortly after the doggie funeral, news quickly spread that Rose Howe had buried Fannie in Green-Wood Cemetery. Some people viewed this as a desecration of the cemetery, especially since the burial reportedly took place “in the most aristocratic portion of the Celebrated City of the Dead.”

In 1889, a person wrote to the editor of the Brooklyn Eagle to ask for confirmation of whether or not a dog was buried at the cemetery. The newspaper said that their call to the cemetery brought a reply that dogs were not allowed to be buried there, and that this was a rule the Board of Trustees had passed a few years ago.

In fact, it was at the annual meeting of the lot-owners of Green-Wood Cemetery on March 17, 1880, held at 30 Broadway in Manhattan, that this specific report of the Board of Trustees for 1879 was read.

In that report, titled “The Records of the Great Burial Ground for 1879,” and published in The New York Times on March 18, 1880, it states:

“The interment in Green-Wood, in a private lot, of a favorite dog, elicited much comment, and was the occasion of many remonstrances, verbal and written, being addressed to the Trustees, requesting them to prohibit such interments in the future.

“The intensity of feeling exhibited in these communications, however differently the subject might be viewed by others, could not but be respected, and the board accordingly passed a resolution prohibiting hereafter all interments of brute animals in the cemetery.”

We know that Fannie died and was buried in 1881 — two years after the Board of Trustees passed this ruling prohibiting animal burials. So that leaves a few questions: Who was the dog that so many people complained about prior to 1879?

Could it have been John E. Stow’s Rex or Laddie, the two other dogs which have monuments in the cemetery? And, was Rose Howe able to somehow bury her loyal friend after the rule against four-footed family members took effect at Green-Wood, or was Fannie buried in Rose’s backyard, as one gentleman told the Brooklyn Eagle in 1889?

What I do know is that the only “dogs” mentioned in the Board of Trustees report for 1881 were the 100 dogwood trees that were planted in the cemetery that year (the lot-owners also introduced 40 gray squirrels to the cemetery in 1881). I also know that in January 1890, Thomas Merchant, superintendent of interments at Green-Wood Cemetery, told a reporter from the Buffalo News that no animals were buried in the cemetery. He was also unable to explain the inscription on Fannie’s monument and declined to discuss the matter.

I guess for now we’ll just have to let sleeping dogs lie.