I have added a new story to my Cats in Hats page. This one is about a cat who worked as a milk steward on the passenger ship S.S. President Harding, which sailed from New York to Germany in the 1920s.

Click here to read this new working cat tale.

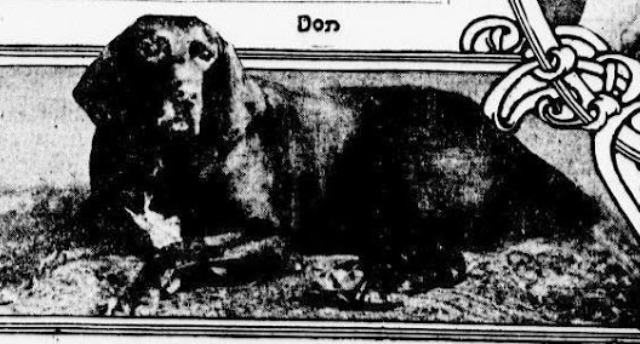

In December 1910, the New York Times ran a large article about a dog who could speak and form sentences up to four words long. The talking dog, described as a “splendid specimen of the German hunting dog” with velvety dark brown fur and beautiful eyes “sometimes almost human in their expression,” lived in a small village in Germany with a game warden named Herman Ebers.

The dog, who had a very Germanic name–Don (ha ha)–spoke in German.

After news of the talking dog spread in the village of Theerhutte and throughout Germany, Ebers began receiving extraordinary offers of up to $15,000 for Don. Ebers, who made only $150 a year as a game warden, decided to hold out for a large metropolitan music hall to bid on his talented dog.

Don, who reporters claimed was either a setter or a pointer, was born in 1905. According to the Times, his power of speech was discovered six months after his birth. The revelation came while the Ebers family was having dinner. When someone asked him, “Willst du wohl was haben? (Do you want something?), Don answered, “Haben!” (Want!).

With only three weeks of training, mostly encouraged by Ebers’ daughter, Martha, Don was able to say three words: kuchen (cake), haben, and hunger. Soon thereafter, he learned how to say “ja” and “nein” (yes and no). He also learned one Russian word: ruble. Martha told the press, “his education is not a matter of force but of his own free choice.”

According to those who heard him, Don was not merely articulating his barking and growling; they could clearly hear “the deep breast tones” that were “unmistakably human in timbre and inflection.”

In 1912, William Hammerstein, the son of New York theater magnate Oscar Hammerstein, set out to get Don. According to reports, he was convinced the talking dog was “a real necessity as an attraction” for his hotel’s summer program.

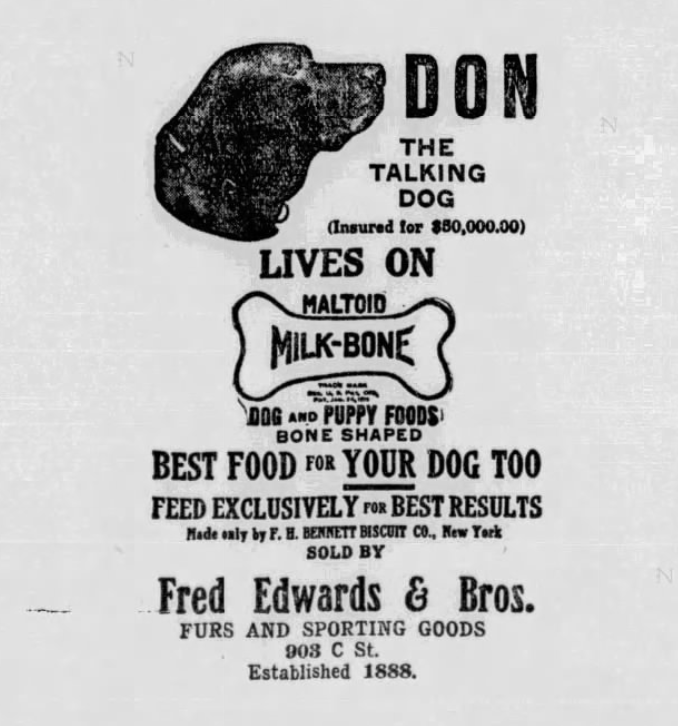

William’s father helped him out by posting a $50,000 bond for the dog. The bond would be paid in the event the dog died on his way to or from America (or from any fatal accident while in America); apparently Lloyds of London refused to insure the dog’s passage and life.

Ebers accepted the offer and turned the dog over to Martha, who would take charge of the dog on his inaugural American vaudeville tour. Martha had recently married Herr Karl J. Haberland, so they combined their honeymoon with the American visit and tour.

Don the talking dog and the Haberlands arrived in America on July 9, 1912, aboard the German steamship SS Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm (they traveled first class because they did not think Don would be safe in the ordinary quarters for dogs). The poor dog was reportedly seasick during the entire trip, and when he reached New York, he refused to be interviewed at the pier. (Perhaps because he didn’t understand English.)

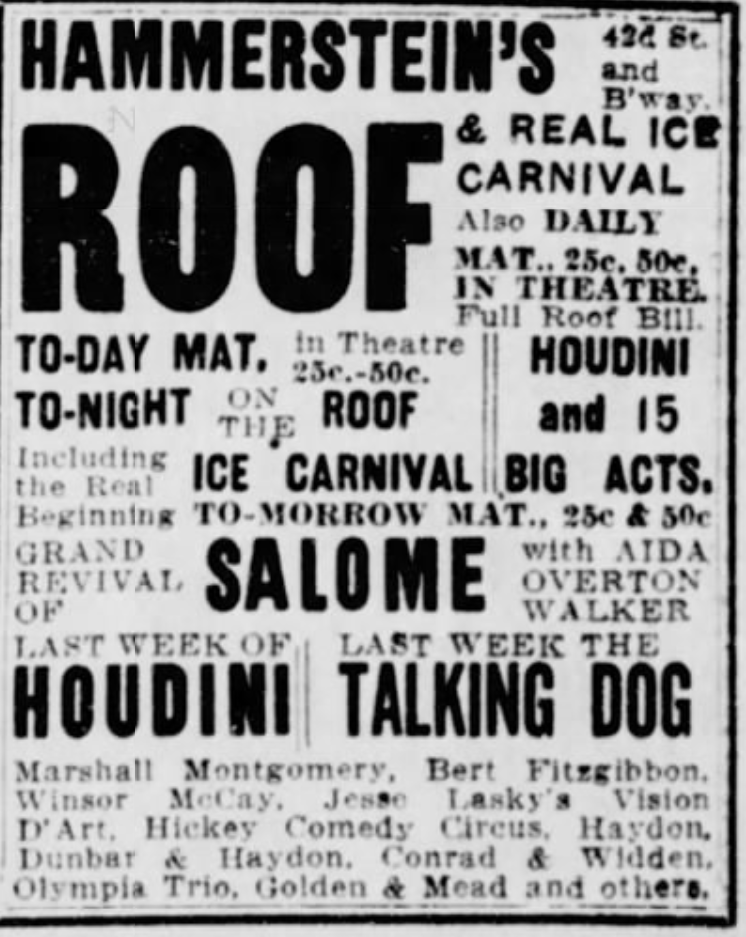

A few weeks later, the German canine made his debut at Hammerstein’s Paradise Roof Garden atop the Victoria Theatre on West 42nd Street. The master of ceremonies who introduced the dog to the audience was Loney Haskell, who also served as an interpreter for the audience.

Don was very nervous at first, and in fact he refused to go on stage until all the windows of the rooftop theater were closed. He didn’t get the greatest reviews–one Variety reporter wrote, “The trained growls which emanate from his throat can readily be mistaken for words”–but the audience was enthusiastic about his novel act.

By the way, one of the other headliners at Hammerstein’s theater that summer was Harry Houdini.

Don stayed in America for a about six months, performing at various New York City stages (he preferred the indoor theaters, as he disliked the sounds of traffic on the rooftop gardens). He stayed in New York for eight weeks before touring other American cities.

During his time in this country, Don began to earn rave reviews. One reporter for the Brooklyn Citizen noted that while he was not a “bench show idol, he has more gray matter than many human beings and is the recipient of much applause.”

Don Saves a Drowning Man at Brighton Beach

In 1913, Don the talking dog returned to New York, where he performed at Hammerstein’s Olympia Theater Music Hall on Broadway in Times Square. He then spent a few months doing the vaudeville circuit in Coney Island.

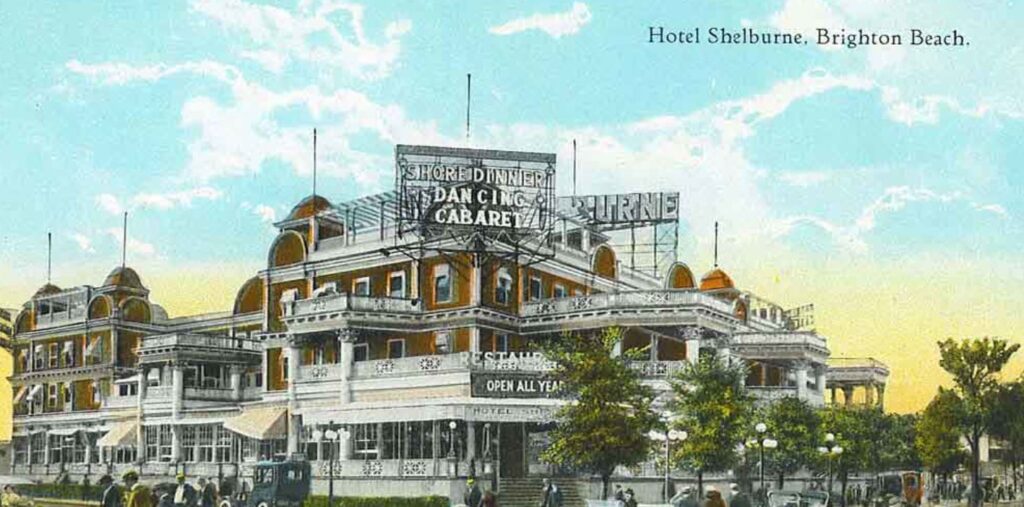

In the summer of 1913, Don and the Haberlands stayed at the Hotel Shelburne at Brighton Beach. On the evening of August 27, Don was frolicking on the beach near the hotel when John Condrica, a waiter at the hotel, began waving his hands as he struggled to stay above water.

Don yelled “Help!” three times as loud as he could, and then ran into the water and swam to the drowning man. According to reports, Condrica pulled the dog underwater in his panic, but Don was able to grab the man’s bathing suit and pull him about 150 feet back toward the shore. (As one astute reporter observed, while this daring rescue was happening, Martha was reportedly thanking her lucky stars that the dog was insured for $50,000.)

Mounted Policeman Edward F. Cody of the Coney Island precinct, who, according to The Sun, “understands German when spoken by a dog,” made a daring leap off the embankment on his horse, Ruler, and charged into the water (Cody did not know how to swim but the horse apparently did).

Holding onto the reigns with his right hand, he grabbed Condrica with his left hand and held the man’s head above water. Three lifeguards from the Parkway baths–Benjamin Hilton, Albert Skene, and Ralph Behring–took out a boat and aided in the rescue. It would not be the first or last time Cody made such a water rescue with his horse.

Don the talking dog died in Dresden, Germany, on November 15, 1915, at the age of 12. Newspapers across the country reported on his death.

A Brief History of the Hotel Shelburne

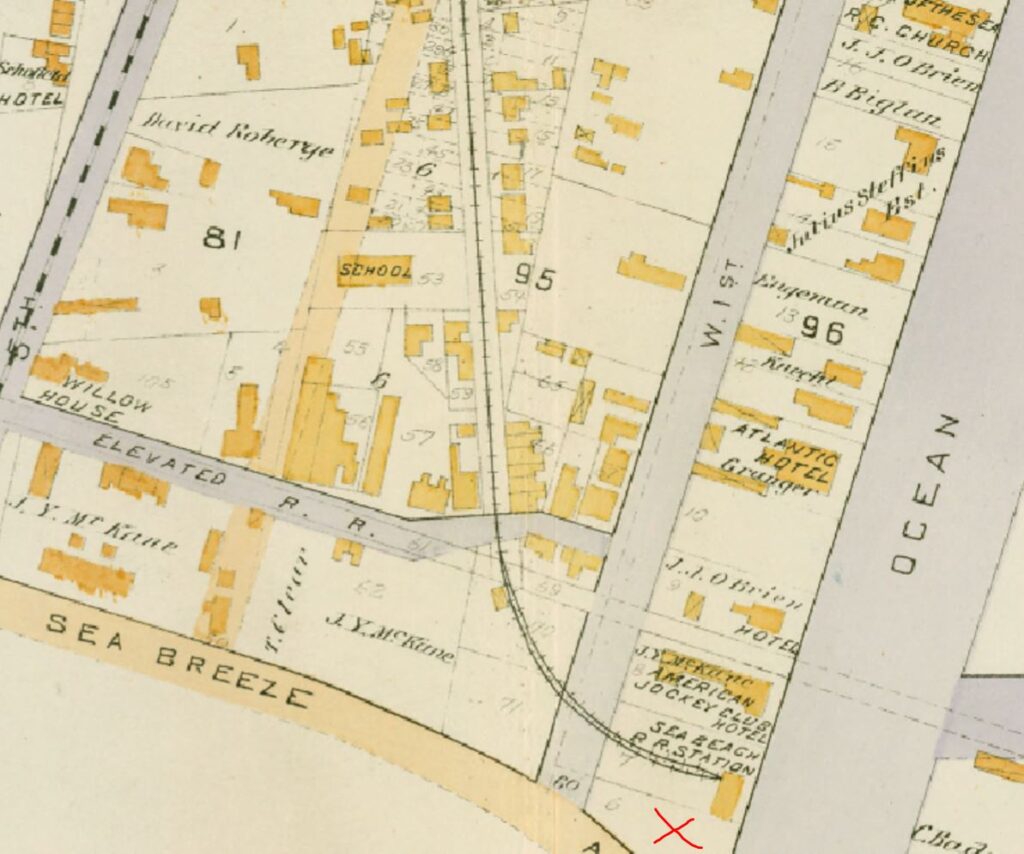

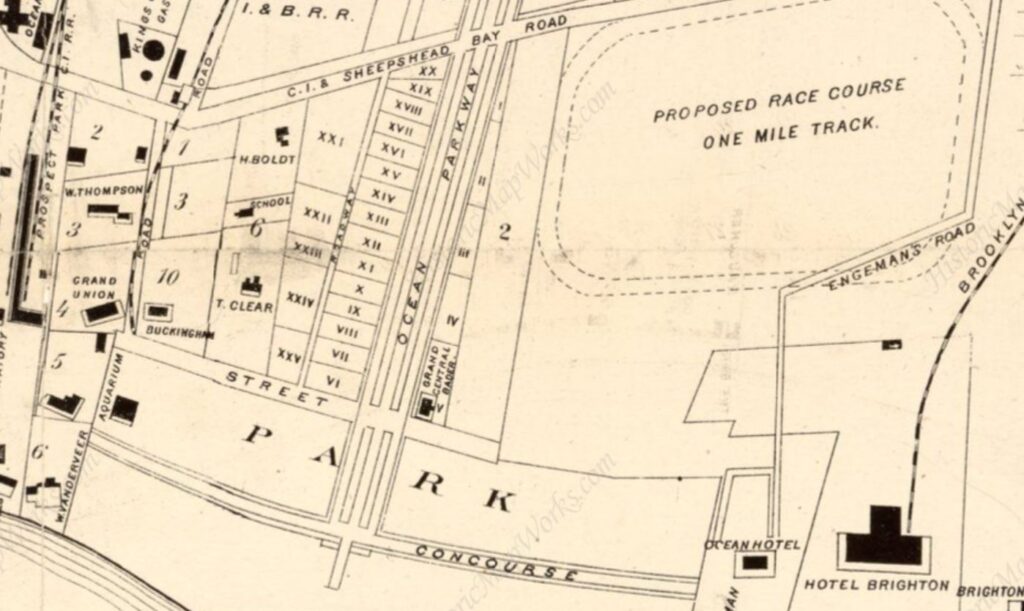

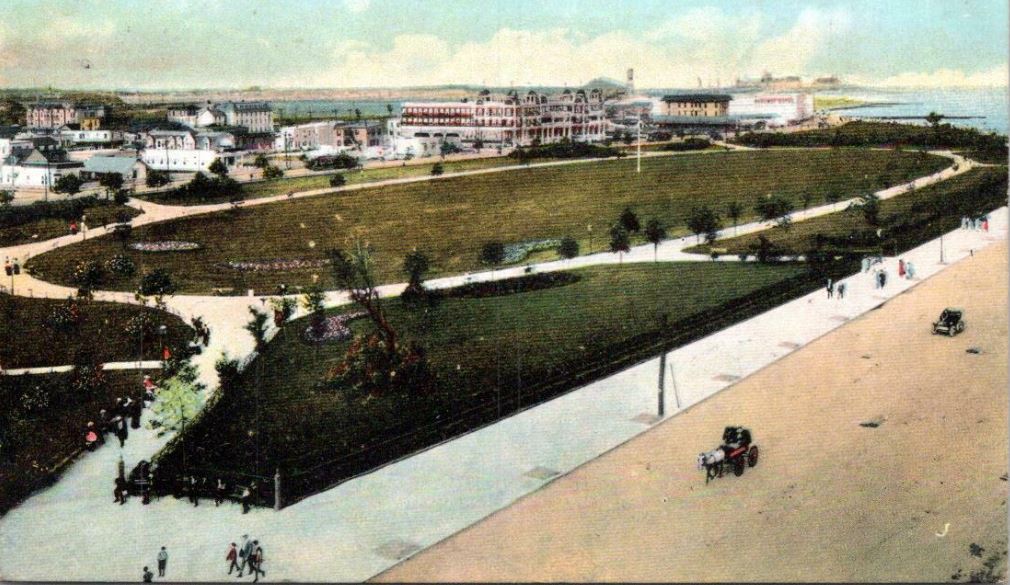

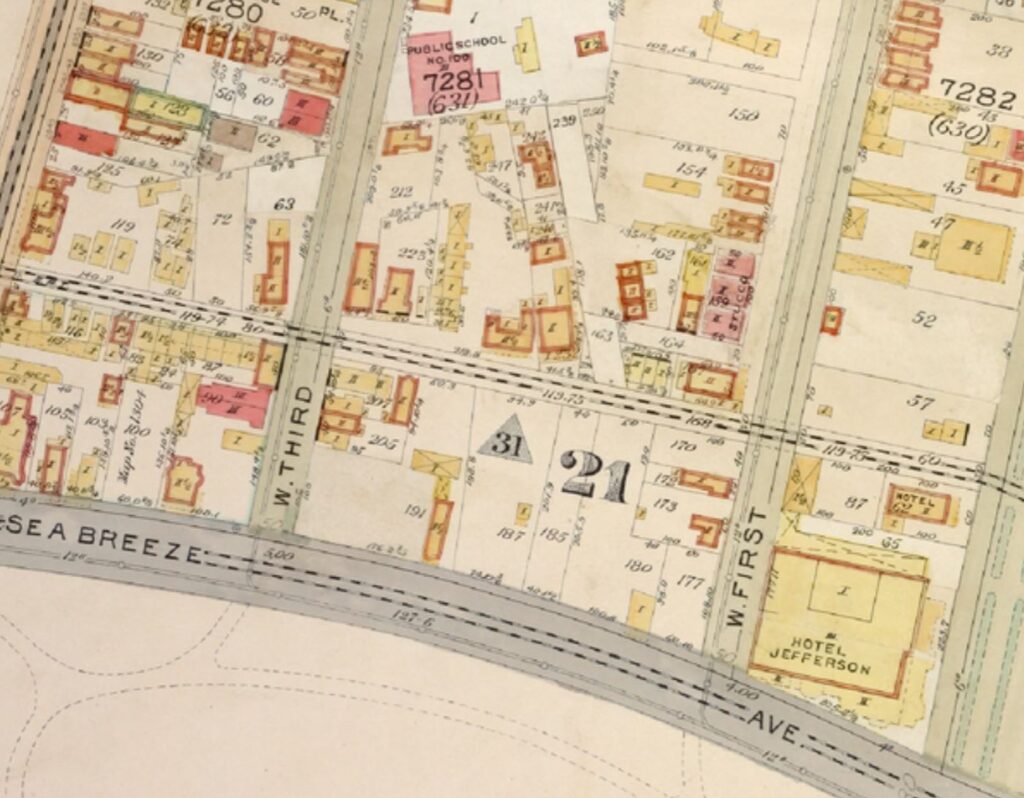

The Hotel Shelburne, where Don the talking dog was staying with his master in the summer of 1913, was a grand hotel in Brighton Beach, bounded by Ocean Parkway, West Brighton Beach Avenue, West 1st Street, and Sea Breeze Avenue. Today, this land is occupied by the Shelbourne Towers–originally known as the Shelburne Apartments (which used the correct spelling when they were built in 1932).

This property once belonged to John Y. McKane, a colorful figure, to say the least, in the history of Coney Island.

Born in County Antrim, Ireland, on August 10, 1841, John McKane moved to Gravesend, Brooklyn, with his family when he was two years old. He trained in carpentry and started working as a carpenter and builder in the Sheepshead Bay area in 1866.

A few years later, McKane was elected constable of Gravesend. It would be his first of several elected positions that would eventually earn him the title of Brooklyn’s Boss Tweed.

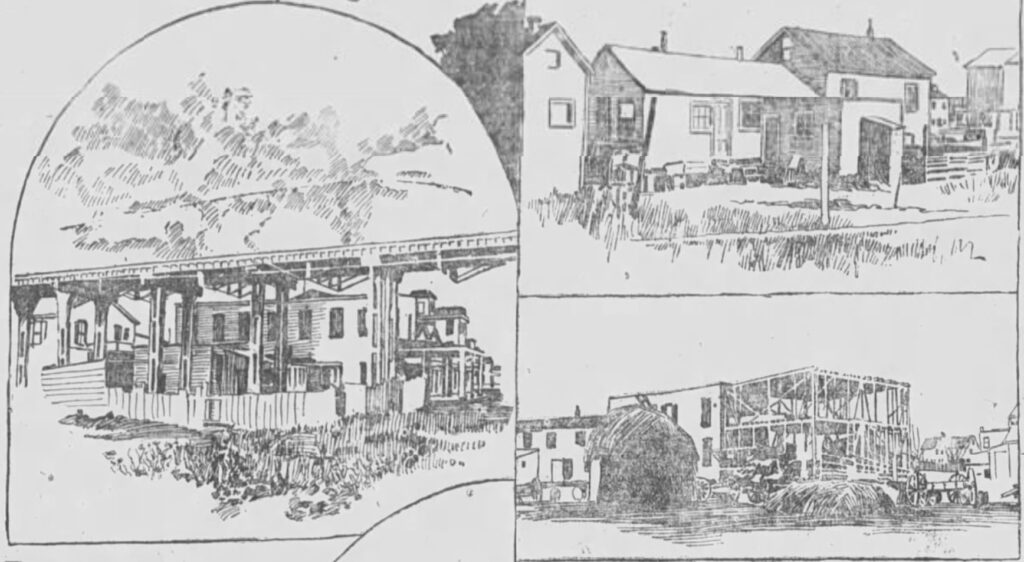

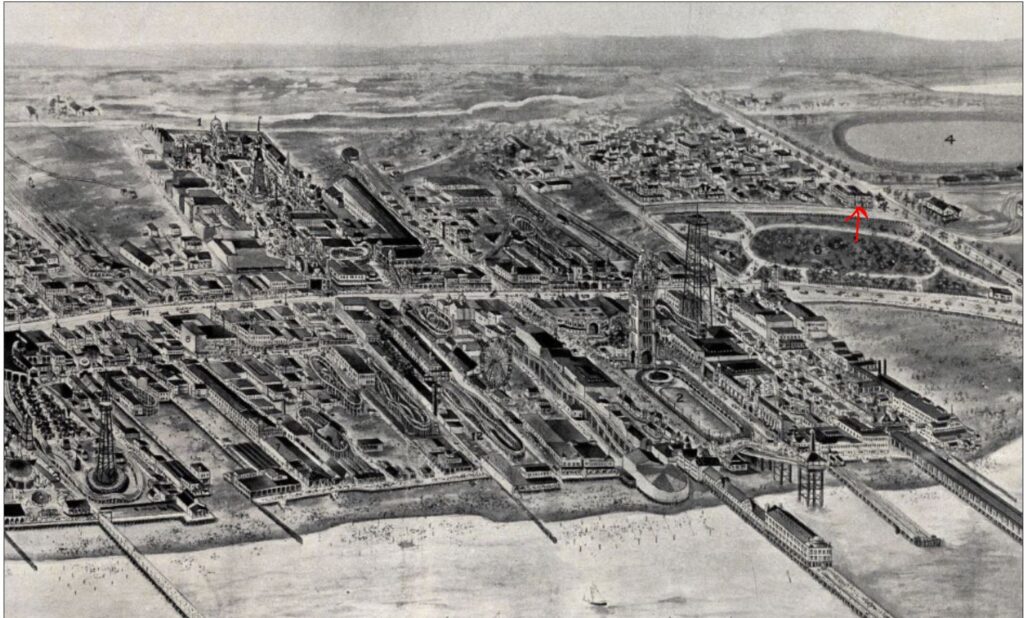

Over his years in office, which included a self-appointed stint as chief of the Coney Island police department, he gained notoriety through a series of shady land deals that gave him enormous political power in city, state, and federal elections. Basically, he named himself Commissioner of Common Lands, which gave him control over all construction in what was called West Brighton.

McKane’s power allowed him to intimidate voters and interfere with election monitors who were responsible for ensuring honest elections.

His corruption seemed to have no bounds, and he earned thousands of dollars by collecting “licensing fees” from the dance and music halls, saloons, seedy hotels, and other establishments that he helped develop in West Brighton.

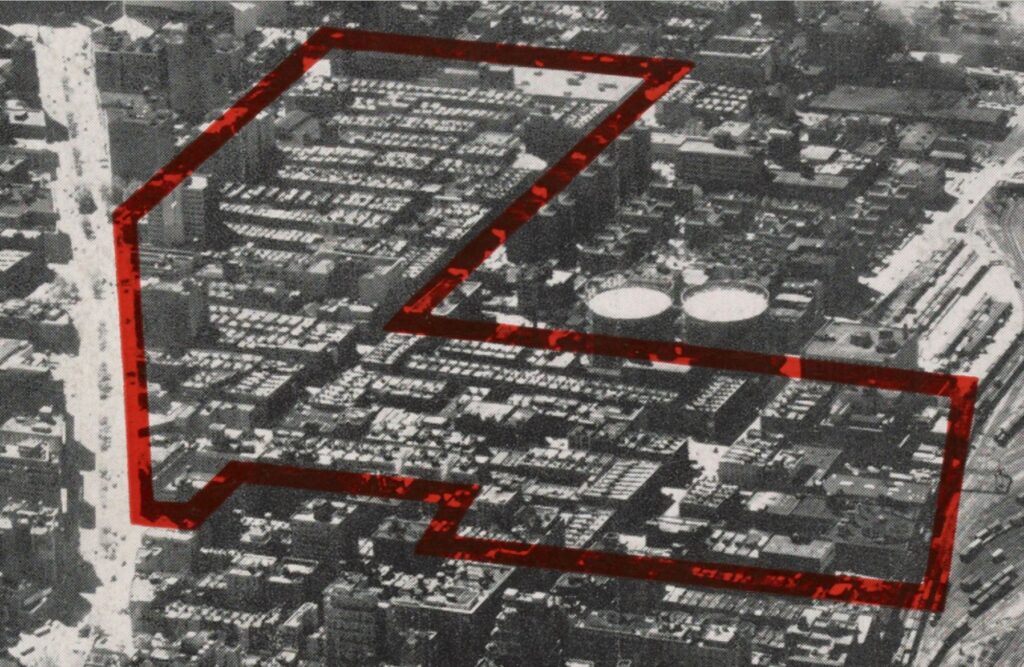

During this era, West Brighton was referred to as “Sodom of the Sea.” One of the worst areas was a community of mostly Black and some Italian residents known as the Gut, bounded by West First and West Fifth Streets, Sea Breeze Avenue, and Neptune Avenue (see the map above). Here, one could find numerous wood shanties and cottages along with beer and dance halls, dive hotels, and brothels.

After creating his own police force in 1881, McKane and his men began raiding the Gut, sometimes taking prisoners and sometimes chasing law-breaking residents off the island. Many of the residents began to tame down in fear of McKane’s wrath, but it really wasn’t until streets were cut through the Gut around 1901 that the neighborhood began to improve.

Although McKane was often charged with various crimes, he always escaped prosecution: too many men owed him favors and too many were afraid of his power to bring them to their knees. But in 1893, he went a bit too far, rigging an election to prevent another candidate from defeating him (he refused to hand over the fake voting tallies to the Brooklyn Supreme Court).

Faced with charges of election fraud, contempt of court, and other charges, he was indicted and sentenced to six years of hard labor at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

According to reports, McKane was arrogant and narcissistic enough to think he would somehow elude imprisonment. Some rumors even spread that some of his Coney Island political henchmen were going to raid the jail and help him escape to Cuba.

Oh well, that didn’t happen, and off to prison he went. Not only was his spirit crushed, but he spent his last years on Earth as a lonely old man: One report said he refused to allow anyone—including his own wife and children—to visit him because he was too vain to let them see him wearing prison garb.

McKane was released two years early for good behavior in 1898, but he suffered a stroke in August 1899. That didn’t kill him, but a second stroke a month later did.

Speaking of history possibly repeating itself, let me get back to the Hotel Shelburne, which was constructed in 1904 on McKane’s land (his widow, Fanny, now owned the property), adjacent to what had been the Gut neighborhood…

The hotel was originally called the New Concourse Park Hotel, in honor of the new Concourse Park across the street on Surf Avenue (where Asser Levy Park is today.) Designed by architect Abraham D. Hinsdale, the large, three-story, wood framed hotel opened in June 1914, just three months after excavation had begun. It was the first grand hotel to be constructed at Coney Island in more than 20 years.

The 150-room hotel had numerous amenities, including a large shed on the property to house horses and up to 300 automobiles (there was also an automobile repair shop—an automobilist lived nearby, and he would run to the hotel if someone needed help). The roof had two Japanese gardens, and the basement had a Turkish bath, swimming pool, gymnasium, billiard room, bowling alley, massage room, and wine cellar.

During its first year of operation, the hotel was run on an elaborate plan that cut into all the profits. The hotel was sold at auction in February 1905, and the name was changed to the Hotel Riccadonna in June 1906. The hotel was named in honor of Abele Riccadonna, an Italian immigrant who made a name for himself as a caterer and restaurateur. Abele died in 1902, but not before ensuring that a Coney Island hotel would one day have his name.

Abele Riccadonna’s wish didn’t last very long. In 1911, the hotel changed hands again, and this time it was renamed the Hotel Jefferson. A year later, the owners of the Jefferson filed for bankruptcy, following a fire in April 1912 that caused about $40,000 worth of damage.

John Reissenweber, a brewer, purchased the hotel and named it the Shelburne. He and his son-in-law, Louis Fisher, enjoyed many years of success, especially with their revues, which were taken from the best shows on Broadway (like Don the talking dog).

One more time, in 1928, the hotel would be sold at a foreclosure sale; demolition began in May. A year later, the site was occupied by three miniature golf courses (called miniature links). Apparently, miniature golf was the pickleball of the late 1920s and 1930s.

The demolition completed the demise of Coney’s Island “Big Four”: the Oriental, the Manhattan Beach, and the Brighton Beach hotels had already been lost to progress. In 1932, the Shelburne Apartments were erected on the site, bringing an end to the hotel’s history.

On September 23, 1962, Philharmonic Hall (now David Geffen Hall) opened with an inaugural concert featuring Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. The concert hall was the first building of Lincoln Center to be completed as part of the Lincoln Square Renewal Project (1955-1969).

About 40 years earlier, this exact location on the Lincoln Center campus was the site of another type of concert: a canine concert of barks and howls from dogs of all breeds and sizes. The dogs were all guests of the Grisdale Hotel for Dogs at 132 West 65th Street. Today this is the address for the David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center.

The hotel was run by Thomas Grisdale, aka The Dean of Gotham, a prominent dog dealer and award-winning exhibitor who specialized in bulldogs.

Born in Temple Sowerby in northern England in about 1865, Grisdale moved to Cleveland in 1885 and began showing dogs in 1888. After moving to New York, he worked for about 25 years as a breeder and exhibitor for William H. Newman, president of the New York Central Railroad. He apparently did such a good job watching Newman’s dogs, that the man rewarded the young Grisdale with an all-expense trip to London.

In 1912, Grisdale broke out on his own to start Gotham Kennels at 540 West 42nd Street (now a parking lot). The kennels were described as “the oldest established bulldog kennel in America,” where Grisdale sold “aristocratic dogs for aristocratic people.”

Grisdale began his hotel for dogs at the Gotham Kennels sometime around 1915. In 1918, he leased a three-story and basement building at 132 West 65th Street from the owner, Janette Ida Luqueer Hurlbut. (Incidentally, it was in this same building that James H. Anderson founded the Amsterdam News on December 4, 1909.)

The hotel featured a reception room and lobby (decorated with paintings of dogs), as well as tiers of “rooms” made up daily by a maid. Canine guests with a day pass could retire to these rooms for afternoon naps and overnight guests would sleep in them at night.

During the day, when they weren’t playing or being walked, pups could relax in the lounging room or sun parlor.

At the Grisdale Hotel, there was also a beauty parlor of sorts for the lady dogs and a barber shop for the male dogs. A tea room where dainties were served in the afternoon, a hospital room for sick guests, and a dental hygiene room provided even the most pampered pooches with everything they could need during their stays.

According to Grisdale, the manicuring department was the busiest department in the hotel. The dental room, where a dog dentist cleaned the dogs’ teeth or pulled teeth as needed if the puppy had too many teeth, was also in demand. Grisdale explained, “In promising bull pups, as in children, the teeth are often too crowded, and it’s better to pull out one or two so as to make a good-looking mouth for shows.”

When it came to food at the dog hotel, Grisdale said, it was “nothing but the best.”

Grisdale told a reporter that many of the dogs, whose mothers would leave them for a few days to “motor down to Long Island or Newport,” received too many sweets at home. These dogs were placed on a diet of eggs beaten in milk until some pounds came off. Then they were given the finest meat chopped finely, the best vegetables, and the most delectable and nourishing biscuits.

In addition to playtime, the dogs were walked every day. The hotel even had its own cab service with a cab specially built with a long bench on each side that was “just high enough for a gentlemanly canine to sit at his ease and look interestedly out of a plate glass window.”

For all these services, canine guests paid $1 a day for room, board, and attendance (the charge was $2 if the dog required additional grooming). Some smaller dogs could stay at the hotel all week for only $3. As the New York Evening World reporter observed, it was the only hotel in New York City with prices not affected by Prohibition.

When he wasn’t working at his kennels or the hotel, Thomas and his wife Emma (nee Martin) kept busy judging or showing their champion bulldogs at the various dog shows in America, Canada, and England. Thomas died in May 1937 at the age of 73. Emma, who was about 26 years younger, continued living in the city and showing dogs. She passed in 1980.

A Brief History of West 65th Street and Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts was the culmination of the Lincoln Square Renewal Project, which displaced more than 7,000 families and 800 businesses within 18 blocks of a neighborhood called Lincoln Square, aka, San Juan Hill. This neighborhood was bounded by Amsterdam and West End Avenues between 59th and 65th Streets.

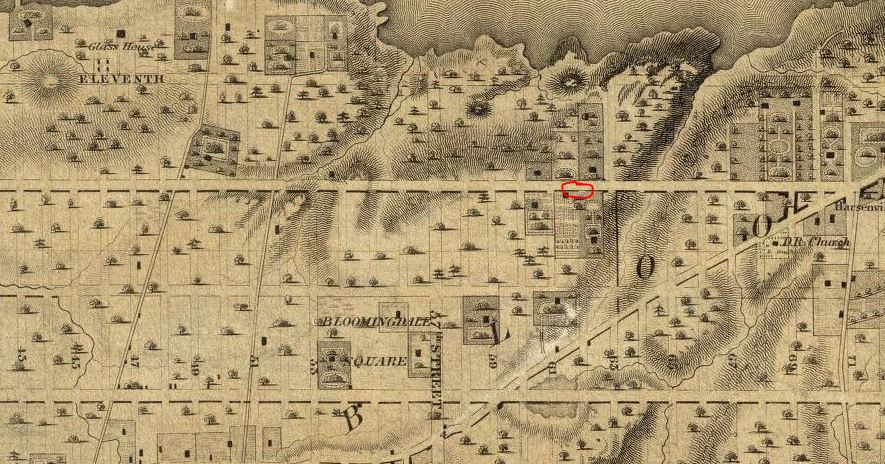

The recorded history of this part of New York City goes back to 1667, when Sir Richard Nicholls granted a patent for a vast amount of land on the west side of Manhattan to Johannes Van Brugh, Thomas Hall, John Vigne, Egbert Wouters, and Jacob Leanders. In the late 1700s, this area was known as Bloemendaal or Blooming Dale–the valley of flowers.

One hundred years later, in 1785, the Van Brugh land (318 acres) was conveyed to John Somerindike for $2,500 by the Commissioners of Forfeiture. From that point it was called the Somerindike (or Somarindyck) Farm. To the immediate north was the small hamlet of Harsenville.

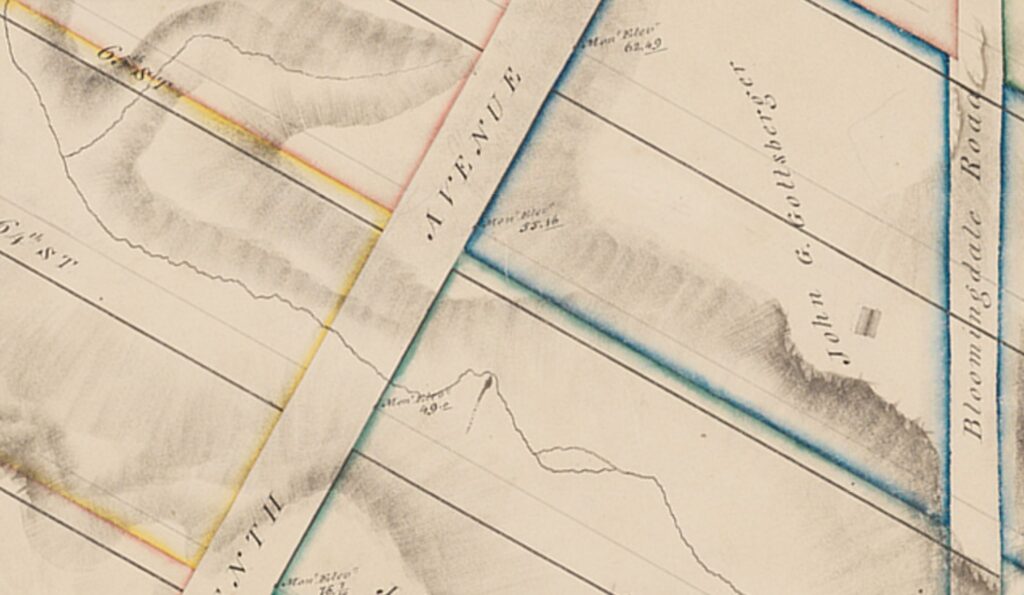

By 1817, the parcel of land where Lincoln Center now stands was owned by John George Gottsberger, an Austrian businessman who had arrived in America in 1811. In fact, the building that may have been Gottsberger’s country home (see below) would have literally been across the street from the Grisdale Hotel for dogs.

The last farm of record in this area was the John Low farm, bounded by 59th and 62nd Streets, the west side of Tenth Avenue, and the Hudson River. Due to its rocky topography, this area did not experience development until the mid-19th century.

Over the years, from the 1880s to the 1950s, the building at 132 West 65th Street was occupied by immigrants from many countries, including Germany, England, Switzerland, Turkey, Ireland, Russia, and the Philippines. The building was last occupied by one household with 12 boarders from Norway, Ireland, and Puerto Rico.

In 1940, the New York City Housing Authority called the San Juan Hill neighborhood “the worst slum section in the City of New York” and made plans to demolish all the old tenements. Nine years later, the Housing Act of 1949 was passed by President Truman under his Fair Deal. Title I, “Slum Clearance and Community Development and Redevelopment,” allowed local governments to take land considered to be slums under eminent domain and sell it to private investors to redevelop.

The act created a perfect opportunity for Robert Moses, who was able to frame San Juan Hill as a slum neighborhood in order to secure sponsors and approval for the Lincoln Center project. City officials called it “the greatest cultural development of our time.”

Fun Fact:

On May 24, 1962, a tuning test took place at Philharmonic Hall to test the acoustics and vibrations. The 2,612 auditorium seats were filled with ragdolls, some which were wired to see if there were any dead spots in the auditorium. A series of cannon shots were fired from the stage.

Prior to this test, before the buildings on West 65th Street were even demolished, vibration measurements were taken in the cellar of Harvey’s Bar at Broadway and West 65th. Those measurements were compared with similar measurements in the basement of the new hall. This test was conduced to see if subway rumblings would be heard in the hall. The results showed that the vibrations were less in the hall than they had been in the bar; the results showed that sounds of the subway would not be heard in the Philharmonic Hall.