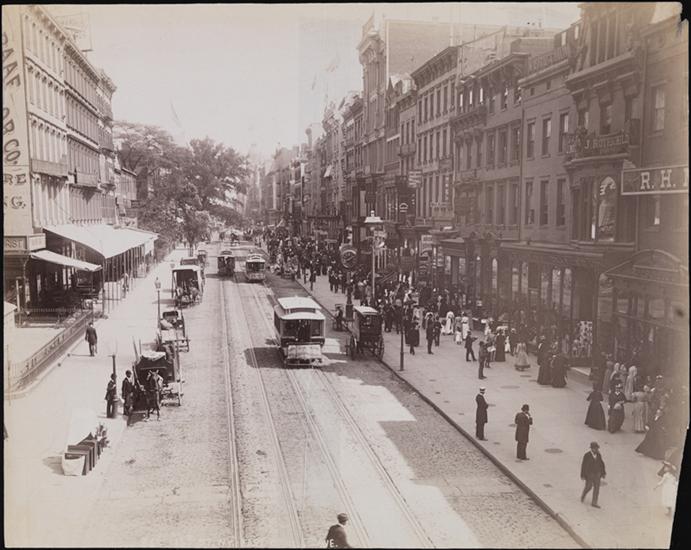

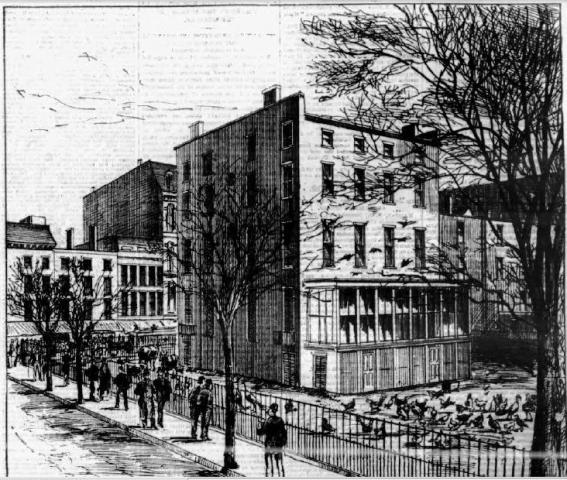

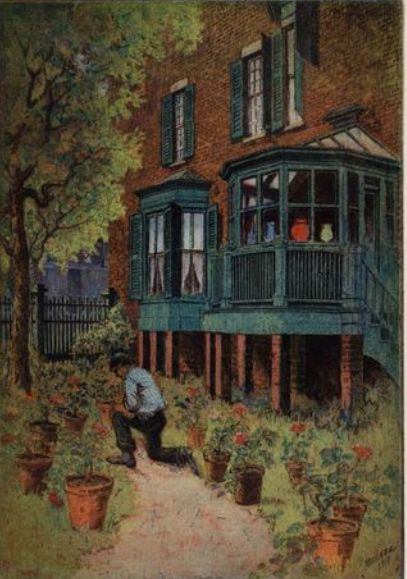

“In a district now given up to department stores, with the trolleys crashing by and the elevated railway within a few yards, it stood, an excellent example of the stately brownstone family homes of a century ago. Its garden is still kept up. Its fine trees give a pleasant shade, and its old fashioned wooden gate and railings speak of the fashion of a bygone age. Until a very few years ago it was maintained as a small farm and the visitor to the city was often brought to see the very last cow which ever browsed in lower Manhattan as it cropped the little stretch of turf.” — New York Times, July 23, 1908, article about the old Spingler Farm

The Other Last Cow Standing

I recently wrote about the old Peter Goelet estate on the corner of Broadway and 19th Street, and the extraordinary spectacle of cows, storks, guinea-pigs, and other animals that fed quietly in the busiest and most bustling part of Manhattan.

In that story, I said that Peter Goelet’s cow was the last to graze on Broadway north of Union Square. While this was not a false claim, I failed to mention that there was another cow still grazing very nearby in New York City at this time, on the north side of West 14th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenue.

The Downtown Farm

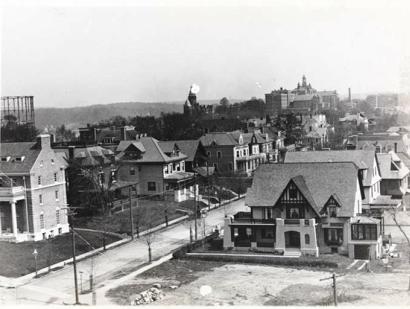

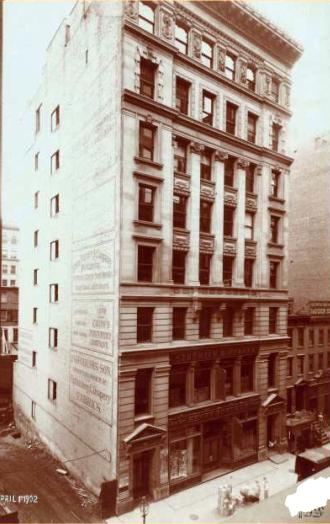

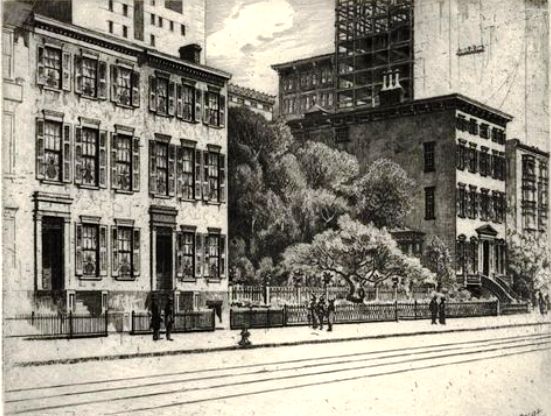

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Van Beuren Homestead was a city landmark, a curious world unto itself surrounded by large department stores and loft office buildings.

The two grand homes at #21 and #29, where the elderly Miss Elizabeth Spingler Van Beuren and her sister Mrs. Emily Augusta Van Beuren Reynolds lived, were connected by a large fenced-in garden that extended to 15th Street.

On the property were chicken coops, dovecotes, arbors, sheds, brick stables, and a conservatory. Up until the the 1890s, a cow could often be seen roaming in the yard as well as two horses and some chickens and doves.

Local residents called the curiosity “the downtown farm.”

The Spingler Farm

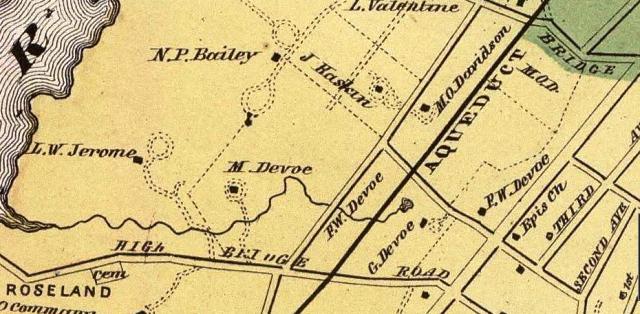

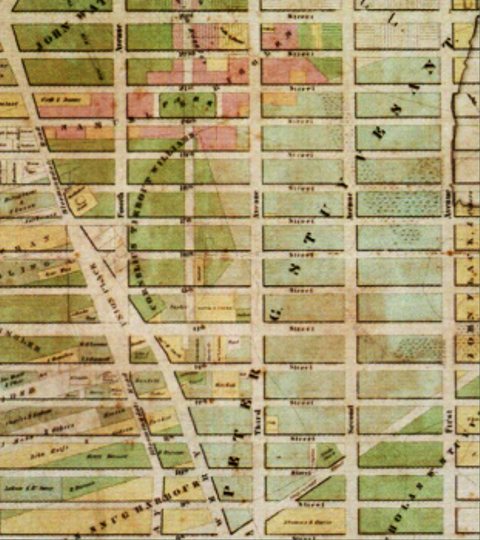

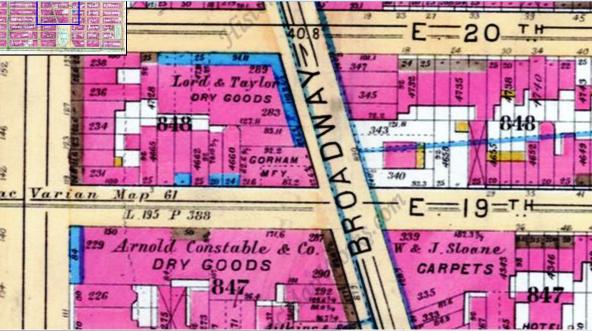

The story of the Van Beuren Homestead really goes back to Elias Brevoort and his wife, Leah Persell Brevoort, who owned about 40 acres of farmland just south of today’s Union Square in the mid-1700s (#56 and #57 on this 1852 Valentine farm map).

In 1762, Elias sold about 22 acres of the Brevoort farm along 14th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenue (#57 in the 1852 Valentine farm map here) to John Smith, a wealthy leather dresser and slaveholder.

John built his country residence in the center of the south side of 14th Street, just west of Fifth Avenue, and a barn on the southwest corner of today’s 14th Street and Fifth Avenue (today’s 80 Fifth Avenue).

On February 29, 1788, following John Smith’s death, New York Mayor James Duane and other executors of John’s will sold the land to Christian Henrich Spengler (Henry Spingler), a German shopkeeper, for 950 pounds (or about $4,700). From that point on, the land was known as the Spingler farm.

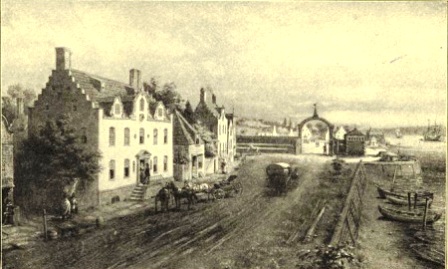

Henry Spingler and his wife, Mary Bonsall Spingler, originally lived in the former home of John Smith, which The New York Times called “a quaintly built Dutch structure.” But according to the newspaper, Henry “soon found that it was lonely living down the lane from the Bowery Road.”

So he built a modern mansion on a hill by what is now part of Union Square. The new Spingler mansion faced the Bowery Road, or what is now Fourth Avenue. Henry lived in this home until his death in 1814.

Sometime following his death, a portion of Henry’s land that included the house on the hill was taken over by the city for construction of a new public square.

At this time, Henry Spingler’s daughter Elizabeth (Eliza) was living in the house with her husband, Lieutenant James Fonderden, and their daughters, Mary, Frances, and Josephine. Undaunted by all the construction activity, the family moved back into the old Dutch farmhouse.

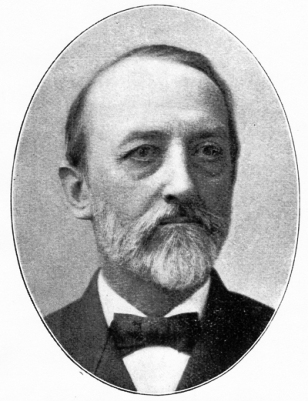

In 1830, 20-year-old Mary Spingler Fonderden married Colonel Michael Murray Van Beuren, a descendant of Johannes Van Beuren, who was a prominent and prosperous Dutch settler in New Amsterdam. The couple had eight children: Elizabeth, Mary Louise, Henry, Josephine, Emily, Michael, Clarence, and Frederick.

Over the years the Van Beuren family lived at 303 Greenwich Street and 35 Bond Street. They also owned a horse farm in New Vernon, New Jersey – what is now the Van Beuren Farms residential development on Van Beuren Road (it took five hours by horse and carriage to make the trip from New York City.)

The Van Beuren Mansion at 21 West 14th Street

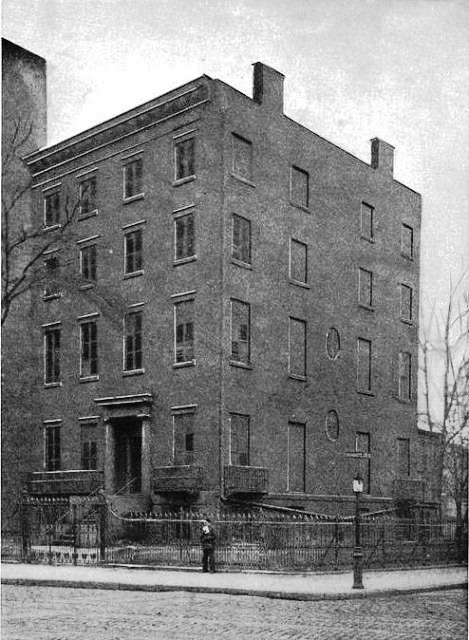

It was Mary Van Beuren who persuaded her mother, Eliza, to leave the old Dutch farmhouse and erect a more suitable home after Eliza’s husband died in 1838. Eliza selected a lot on 14th Street just to the east and across from the farmhouse and constructed a double brownstone in the style of the old Spingler mansion.

The new mansion at #21 was four stories high over a very deep English basement, and it stretched five bays wide. There were stone balconies flanking the entrance, rosewood doors and interior woodwork, and an iron picket fence protecting the wide lot.

Mary and Michael Van Beuren and their children moved in with Eliza sometime around 1940.

The Death of the Van Beuren Matriarch

On August 8, 1894, about 15 years after her husband died, Mary Van Beuren died in the family mansion. The New York Times reported:

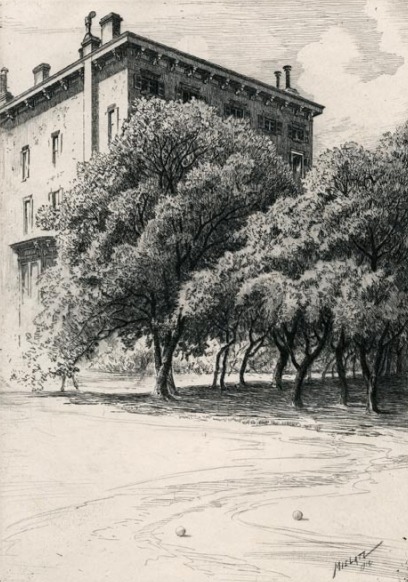

“The great brownstone house in which Mrs. Van Beuren lived a retired life in the midst of the bustle of one of New-York’s busiest retail business districts, has long been a source of curiosity to those not acquainted with its history and the history of the Van Beuren family. Standing back from the street, and surrounded by ample grounds, it has the appearance of a country mansion out of place.”

Following Mary Van Beuren’s death, several of her adult children continued to live in the house, including her widowed daughter Mary Louise Davis and her children (daughter Louise and twin sons Michael and John), her son Frederick and his family, and her unmarried daughter, Elizabeth. Across the garden, at 29 West 14th Street, another widowed daughter, Emily Augusta Reynolds, made her home.

On January 31, 1902, Mary Louise Davis died at the home. She was laid to rest in the Spingler vault at the St. Mark’s Church graveyard on Second Avenue and 10th Street.

Over the next six years, her spinster sister Elizabeth would watch several funerals and marriages take place at the home.

When Elizabeth Van Beuren died on July 1, 1908, at the age of 79, many people were reminded of the the never-married Peter Goelet and his residence on 19th and Broadway – they assumed that, as did the Goelet residence, the Van Beuren house would also be demolished and replaced by an office building.

However, Emily Reynolds, still living next door, was quick to squash ideas of development. As the New York Tribune noted, “Mrs. Reynolds said yesterday that the Van Beuren homestead would still be kept intact, in spite of the death of her sister.”

The End of a Dynasty

By the time Elizabeth passed, her sister Emily had been a widow for more than 25 years. She had also lost two sons: Frederick died in 1892 at age 11 and James died of typhoid fever at the Morristown farm in 1895.

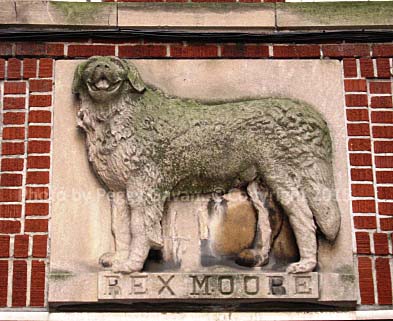

In 1908, the same year her sister passed, Emily Augusta Van Beuren Reynolds purchased a mansion at 1069 Fifth Avenue (88th Street) in a foreclosure deal. She moved into this home and died there in February 1914 with an estate of $3.8 million, including the mansion — valued at $250,000 — a one-quarter interest in 135 parcels of Manhattan realty, and a $7,000 diamond and pearl dog collar. All of her estate went to her daughter, Mrs. Josephine Thomas.

Although the old home at 21 West 14th Street stayed intact for many years, all of the Van Beuren occupants had moved out and relocated uptown or to New Jersey by about 1909.

In 1911, the widening of 14th Street necessitated the removal of the ornamental high stoop, and many of the fine garden trees were taken down.

The two homes with their gardens and outbuildings survived until 1927, after the Spingler-Van Beuren Estate, Inc., which held title to the vast holdings, placed the vacant portion of the lot on the market for a long-term lease.

A company called 25 West Fourteenth Street Corporation reportedly leased the land to the west of the old mansion.

Then in 1927, The New York Times reported that the landmark home was being demolished to be replaced by a nondescript theater and office building.

At that time, the 23,000 square-foot property was assessed at about $12 million. Today, where cows and horses once grazed, and beautiful trees and flowers bloomed, there are retail stores and a very imposing but bland brick apartment building.