On April 26, 1915, the Mounted Policemen’s Association hosted a dinner at the Hotel Majestic in Manhattan. Two of the many honored guests were Patrick J. Doody and Edward T. Cody, both mounted policemen with the 168th Police Precinct in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn.

At the dinner, Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, “The Boy Mayor of New York,” quashed a rumor that mounted police were going to be replaced by bicycle police or motorcycle patrols. Although he admitted that motorcycles were necessary in New York’s outlying districts because of their speed, he pointed out that horses were still necessary because motorcycles could not jump over fences or ditches.

“Some people seem to feel the day is coming when the horse is going to disappear from the police department” Mitchel told the men. “I do not for one believe so.”

Two months later, Patrick Doody and Edward Cody would prove their worth as mounted policemen in Sheepshead Bay, during the greatest roundup of goats in the history of Brooklyn.

James Murdock and His Law-Breaking Ways

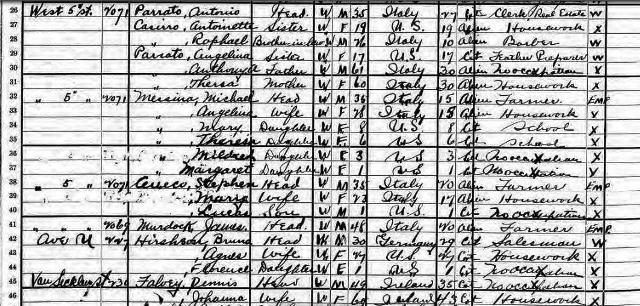

Before I tell you about the goat herding in Sheepshead Bay, let me introduce you to the goats’ owner, James Murdock, or Jimmie, as he was called.

Jimmie Murdock was born in Italy in 1867 (give or take a few years). He arrived in Brooklyn around 1903 and began working as a farmer. By 1910, he was a self-proclaimed dairy man with about a dozen cows and two bulls. He reportedly lived with the cows in a barn on 11th Avenue at 64th Street in the Dyker Heights section of Brooklyn.

Jimmie had a problem abiding by the big city laws, and he was often arrested for violating the Sanitary Code, trespassing, creating a public nuisance, using insulting language, and numerous other minor crimes. In June 1910, he stepped over the line of petty offenses and was arrested for committing a felony.

According to news reports, Jimmie allegedly attacked two women on separate occasions and held them prisoner in his barn. Brooklyn resident Helen Wilson told police she was attacked and held hostage in the barn for an entire night. Another woman, 19-year-old Pauline Kreyeka, said she had been attacked by three men in the barn and also held prisoner overnight.

The police arrested Jimmie and took him to the hospital where Pauline was being treated. She identified him as one of the men who had attacked and robbed her of $100 and a gold chain. Jimmie was held on $2,000 bail at the Fifth Avenue Magistrates’ Court.

I’m not sure if Jimmie spent any lengthy time in jail, but I do know that he was arrested again in December 1912. The problem this time was that Jimmie did not have a license to keep cows on the property, nor did he have a Board of Health license to sell cow’s milk. Magistrate Nash of the Fifth Avenue police court fined him $50 for failure to close the stable.

Jimmie Loses His Bay Ridge Home

Forced to close his dairy business on 11th Avenue, Jimmie moved into a make-shift home – a collapsible shack made out of sheet iron — on 8th Avenue at 62nd Street in Bay Ridge. He brought the cows and bulls with him, along with several dogs and cats. Without any enclosure to protect them, the animals roamed freely in vacant lots and neighbors’ yards.

As time passed and builders crowded him out of his temporary home site, Jimmie would drag his dwelling a few hundred feet down the road and set up house again. No surprise, the neighbors did not like Jimmie Murdock.

In 1914, the Health Department finally seized his bulls and cows. Jimmie responded by stocking up on more dogs and a herd of 16 to 40 goats (the estimates widely varied, depending on which neighbor complained). When he was threatened with seizure again, he enclosed the herd in a ramshackle corral made of rusty bed springs, tin, branches, and boards.

On November 3, 1914, Jimmie’s shack burned down. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported damages totaling about 60 cents, not including the cost of water needed to extinguish the blaze. None of the animals were injured in the fire, although Jimmie told Lieutenant Sloan of the 171st Precinct that three cats and some dogs went missing during the incident.

Goats Gone Wild

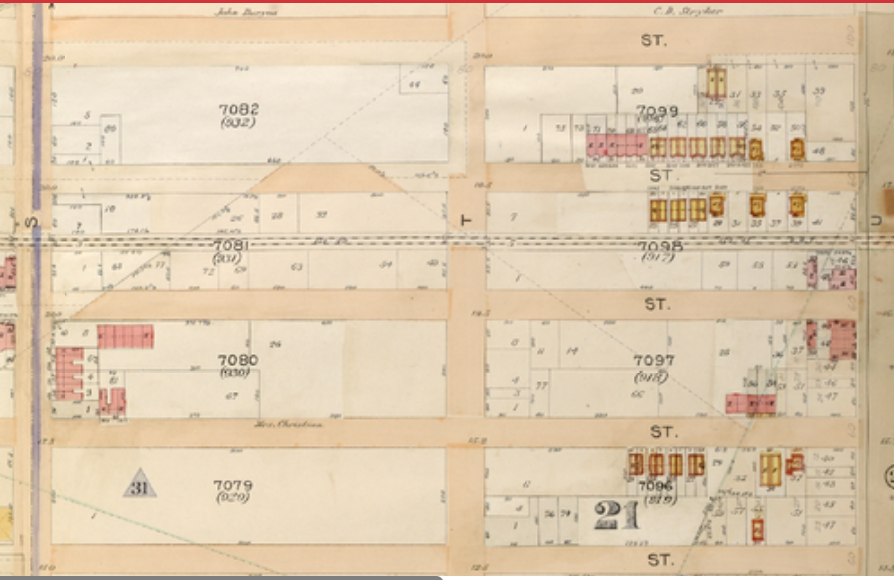

By July 1915, Jimmie was living in some type of structure on West 5th Street at Avenue U in Gravesend. As they had done everywhere else, the neighbors often complained to the police about the sounds and odors coming from his small barn.

By this time, Jimmie had about eight dogs and 63 goats, give or take a few. Whenever he was arrested and fined for having the goats, he’d tell the magistrate at the Coney Island Magistrates’ Court that he needed the goat’s milk to treat his rheumatism.

Only July 13, Magistrate Alexander H. Geismar said enough was enough. He was tired of seeing Jimmie in his court, so he charged him with keeping goats without a permit from the Health Department and gave him the choice of paying a $100 fine or going to jail for 30 days. Jimmie couldn’t pay the fine, so he took the second option and was whisked off to prison.

Now, the problem was that Jimmie lived alone, and he didn’t have anyone to care for his dogs and goats. So the animals were left to fend for themselves in the small barn. All night long the goats bit at the enclosure – the neighbors didn’t bother to complain about the noise this time — until they finally broke away and spread out all over the neighborhood.

“Ki-ya!”

Once free, the 63 goats and eight dogs began running wild through the vacant plots on West 7th Street. Then they scattered about and charged into people’s yards, eating clothes on the lines and nibbling on flowers in the manicured gardens.

Complaints came pouring in at the Sheepshead Bay police station on Avenue U at East 14th Street. Lt. James J. McCarthy sent five mounted policemen to the scene, including Patrick J. Doody, Edward T. Cody, John Walker, Joseph C. Carty, and Henry B. Nichols.

As it turns out, Mounted Policeman Doody was a former cowboy who learned his trade on the southwestern plains. He ordered the cavalry to round up all the clotheslines they could find so they could lasso the goats. Bellowing a mighty “Ki-ya!” and twirling his lasso about his head, Doody lead the team as they captured 42 of the runaway goats.

Once captured, the goats were brought to the police station. The dogs were sent to the SPCA stable. The goats were later taken to a stable at Lake Street and Avenue T – the butcher who owned the stable said he would sell the goats.

After serving his 30 days in jail, Jimmie went home to find that all his goats had been taken away. He started shrieking and going hysterical. Mounted Policeman Walker responded and took poor Jimmie Murdock to Kings County Hospital for observation.

I don’t know what happened to Jimmie after this incident, but it’s interesting to note that Policemen Doody and Cody were transferred to motorcycle duty two weeks later.

A Short History of the Sheepshead Bay Police Station

For anyone interested in police history:

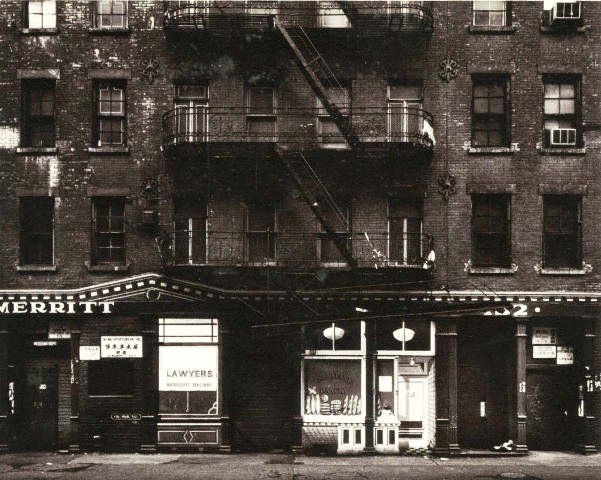

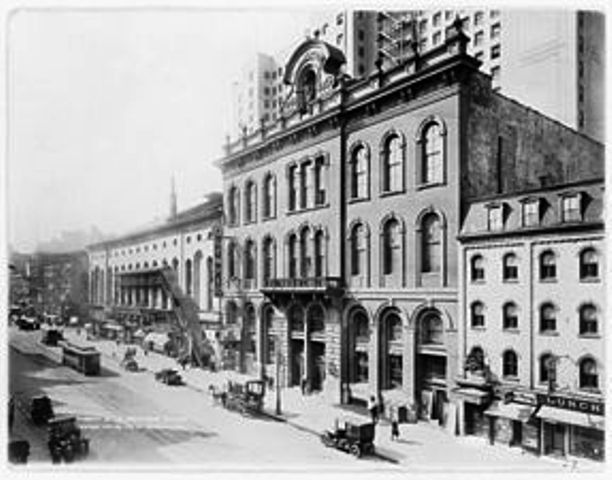

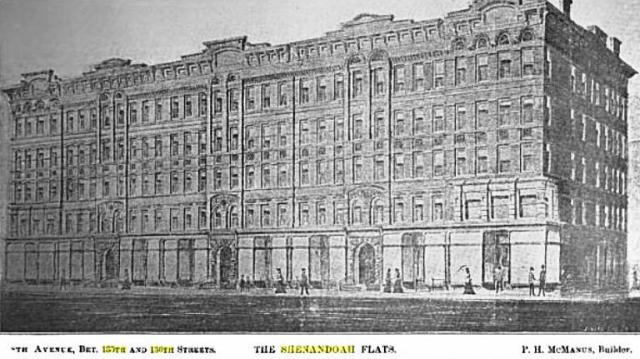

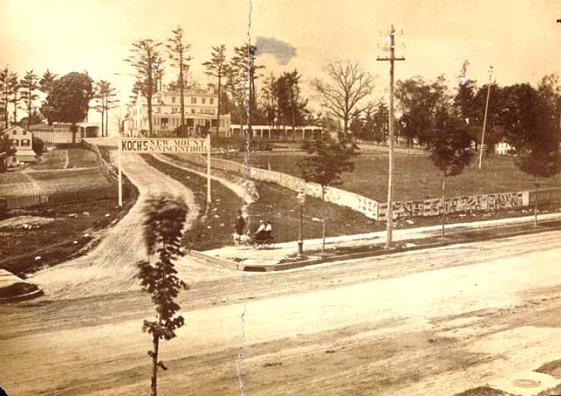

The Sheepshead Bay police precinct was added to the Brooklyn police department in 1892. Prior to 1904, the station was located on Voorhies Avenue, about 150 feet west of Sheepshead Bay Road. According to the New York Sinking Fund Commissioners proceedings of 1904, the old station was a two-story mansard and cellar frame building, about 40 x 40, on a high brick foundation. It had 20 rooms and a bathroom, and three brick cells in the cellar. At high tide, any prisoners in the cells would have to stand on benches because the water would rise two feet.

In the rear of the station house were a one-story frame barn and two other smaller frame buildings. The department was leasing the property for $1,200 a year when plans were made to construct a more accommodating building. The site selected was in the heart of the Homecrest neighborhood, which had seen a rash of home burglaries in the early 1900s.

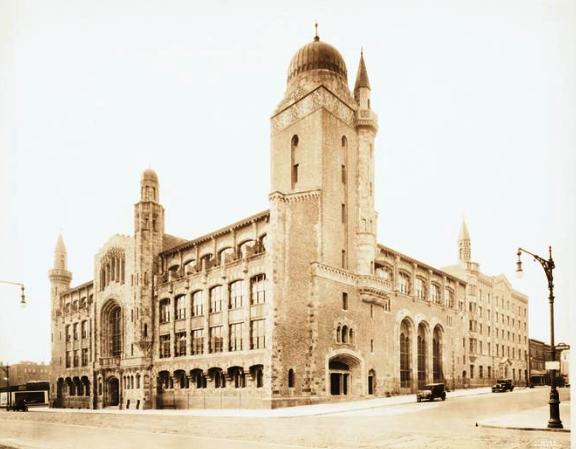

According to the Annual Report of the State Commission of Prisons, Volume 26, the new station house at the northwest corner of Avenue U and East 14th Street was constructed in 1904 and cost $90,000. Over the years, the Italian Renaissance Revival-style station housed the 168th, 72nd, and 61st precincts. In 1977 the 61st Precinct moved to 2575 Coney Island Avenue; the building was demolished in 1979. Today the site is a Duane Reade pharmacy.