What does a tiny dog named Pinky Panky Poo and the Plaza Hotel have to do with modern-day doggie day-care centers? Read on…

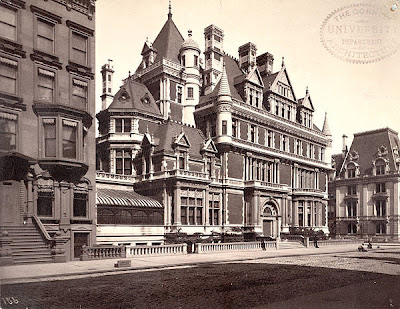

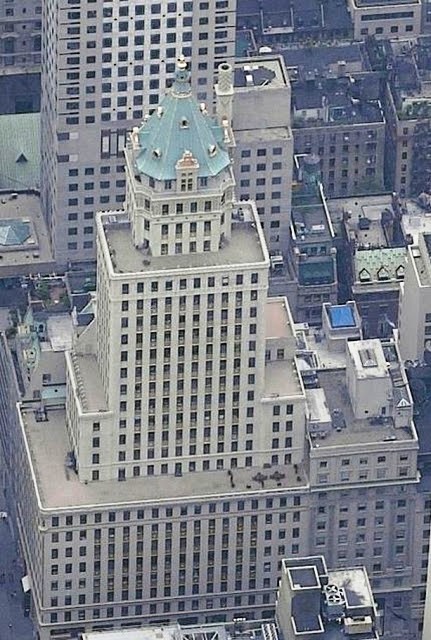

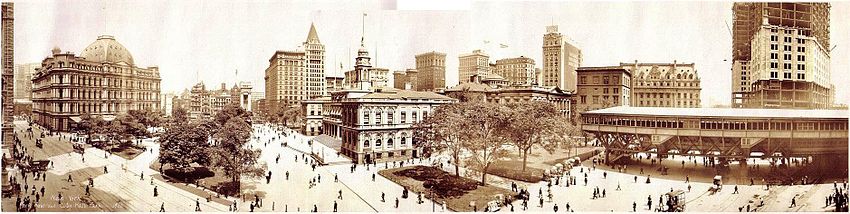

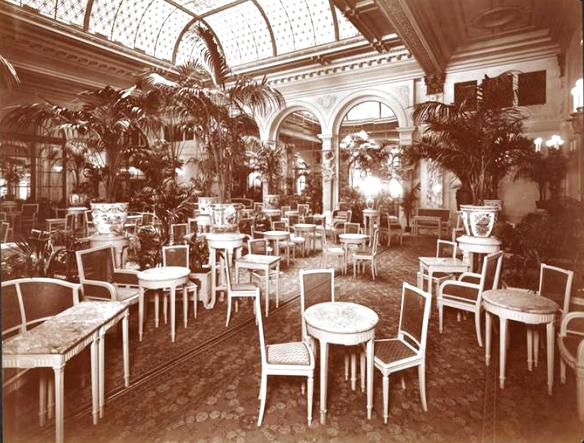

Shortly after the Plaza Hotel opened in New York City in October 1907, afternoon tea at the iconic hotel became a popular way for the women of high society to idle away the hours. The tea room – later called the Palm Court – was patterned after the informal rooms at the Ritz in Paris and the Carlton in London, and had a very relaxing atmosphere. It was so informal, in fact, that the ladies assumed their canine companions would also be quite welcome there.

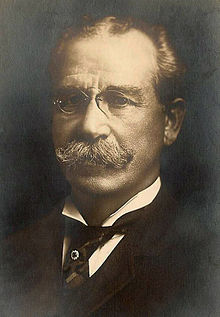

At first, management turned a blind eye and allowed the little dogs to accompany their mistresses to tea. But when the barks and growls and cooing of pet names began interrupting Nahan Franko and his orchestra, managing director Frederic Sterry had to put his foot down. As The New York Times noted, “informal tea is all very well, but the dogs were too aggressively Bohemian.”

Before I continue this story, I must explain why the women assumed their dogs would be welcome at tea in the first place – and why the Plaza Hotel still has an open door policy for small pets today.

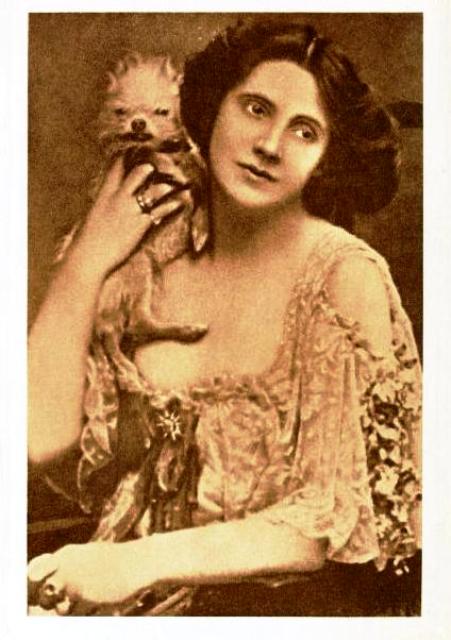

According to Curtis Gathje, author of “At the Plaza: An Illustrated History of the World’s Most Famous Hotel,” our furry friends owe their gratitude to British actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell and her beastly little dog called Pinky Panky Poo.

The following is their story – it’s one from the file I like to call “You can’t make this stuff up.”

A Monkey Griffon Named Pinky Panky Poo

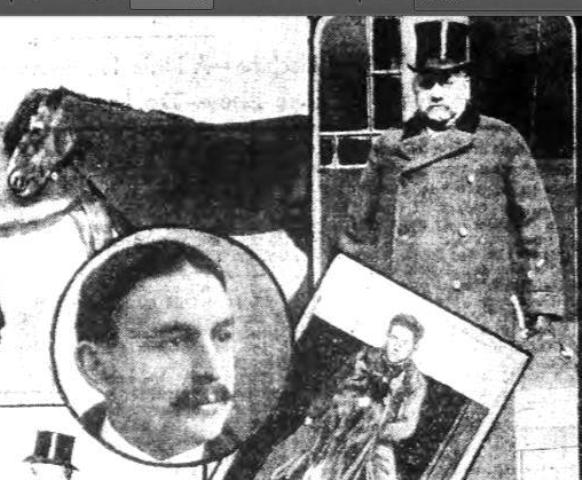

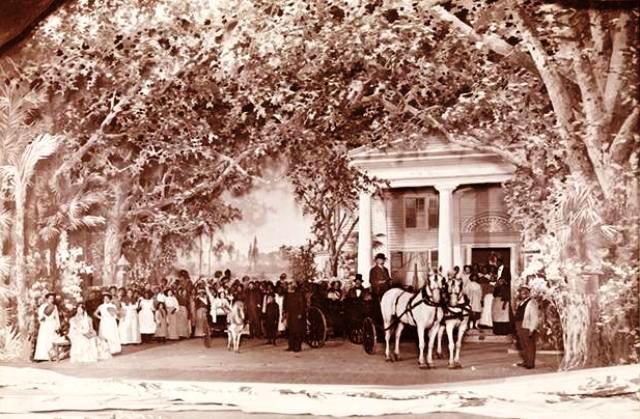

In 1907, Mrs. Patrick Campbell traveled from Liverpool to New York to embark on her second American theater tour. Her schedule included lead roles in several plays, including “The Second Mrs. Tanqueray,” “The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith,” and “Hedda Gabler.”

Mrs. Pat, as her fans called her, arrived in New York City on November 9 with her daughter, Miss Stella Patrick Campbell, her son, Mr. Alan Urquahart Campbell, and her tiny monkey griffon, Pinky Panky Poo. (Mrs. Pat was a widow; her husband had died in the Boer War in 1900.)

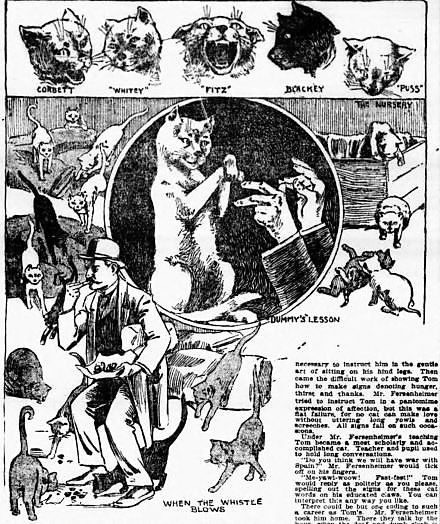

As Mrs. Pat had previously performed in New York at the Theatre Republic in 1902, the press was already quite familiar with the flamboyant actress and her inseparable canine companion. In fact, on her first American tour, the little dog took center stage in almost every major news article about the visiting actress.

The New York Dramatic Mirror had described the dog as having “bright, black, beady eyes; hair that in a less distinguished dog would be called weedy, and paws like overgrown spiders’ legs.” One New York State newspaper even wrote an ode to Pinky, calling him a “high-bred puplet” and “sniffy little beast from kennels of a king.”

So when Mrs. Pat arrived in 1907, the New York Herald reported that even though the little dog was clad in a coat of Astrakhan fur, “he seemed but a shadow of his former self.” At 17 years old, Pinky weighed less than a pound and was nearly blind – apparently from several cat fights. He was also missing all his teeth. Still, Mrs. Pat treated the senior dog as if he were a prince.

Pinky and Pandora’s Box

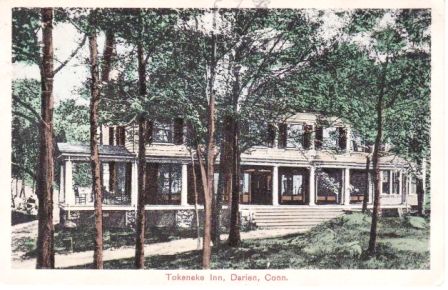

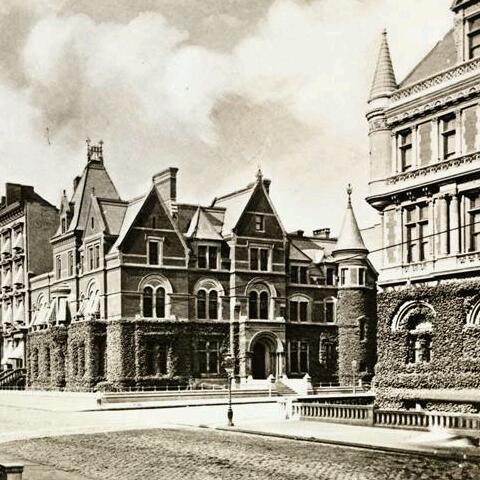

For her second U.S. tour, Mrs. Patrick Campbell had made arrangements to stay at the brand-new Plaza Hotel. But when the family arrived there that afternoon (with several servants and about 100 trunks in tow), they were shocked to discover that the hotel did not allow dogs. Oh, the horror!

Fred Sterry realized that rejecting Pinky Panky Poo would cause a public relations nightmare for the Plaza Hotel, so he decided right on the spot to allow small pets in the hotel. Mrs. Pat had to sign an agreement making her responsible for the dog’s good conduct.

Poor Pinky was also relegated to either the maids’ or baggage elevators. But on that day in 1907, Pandora’s Box was opened, and every woman in Manhattan felt entitled to treat her own pup to an afternoon or longer stay at the Plaza Hotel.

A. Toxen Worm and Mrs. Pat’s American Theater Tours

The newspaper men and press agents had a field day with Pinky Panky Poo whenever he and his mistress visited New York. One theatrical press agent in particular, a man known as A. Toxen Worm, had a great deal of fun reporting on Pinky, and often used the dog in wacky stunts to generate more publicity for Mrs. Pat.

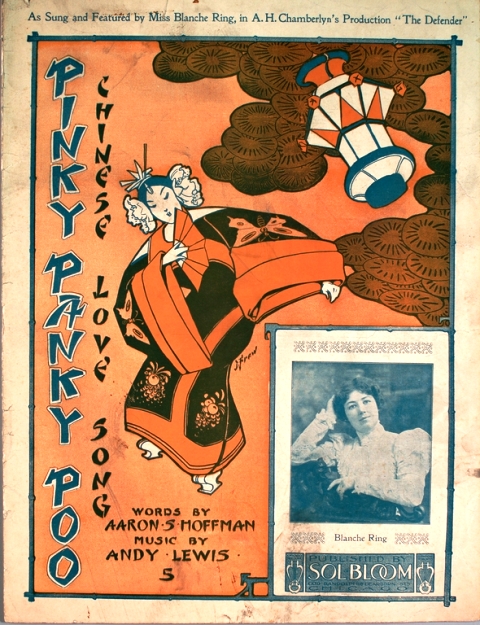

One published report suggested that it was Worm who gave the dog his ridiculous name — newspaper editors and the American public just loved it, so it stuck. If this is true, he no doubt got the idea from “Pinky Panky Poo; Chinese Love Song,” which was featured in “The Defender” at New York’s Herald Square Theater in the summer of 1902.

(And speaking of silly names, Worm’s actual name was Conrad Henrik Aage Toxen Worm.)

In the fall of 1902, Mrs. Pat arrived in New York aboard the Oceanic from Liverpool. According to several news reports, Pinky Panky Poo was cordially disliked by many passengers due to a disturbance he created one night when a bagpiper was playing.

Mrs. Pat had disrupted the performance by calling to her secretary to attend to the dog because she thought he must be frightened. Several passengers reportedly plotted to send Pinky overboard, but they obviously never carried out the act.

During her 1902 tour, Mrs. Pat and Pinky Panky Poo stayed at the Fifth Avenue Hotel. One day while bathing Pinky in imported cologne, she applied a little much, which made him quite ill. She got a call from the hotel while she was rehearsing for the play “Aunt Jeannie” at the Garden Theater, and immediately put the rehearsal on hold.

Mrs. Pat thought for sure the little dog had been poisoned by a flea repellant, but when she told the “host of medical experts” who were summoned to the hotel about the dog’s routine cologne bath, they were able to find a remedy to cure him (probably a bath in soapy water).

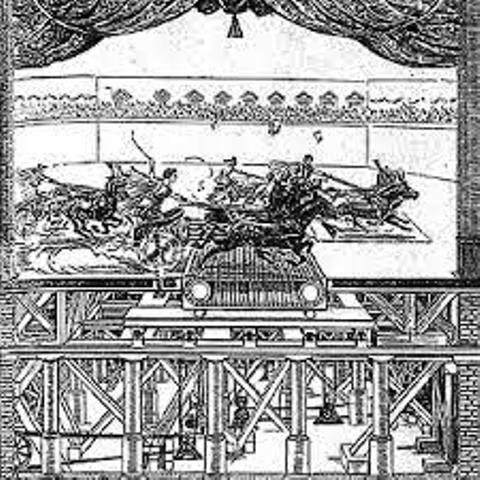

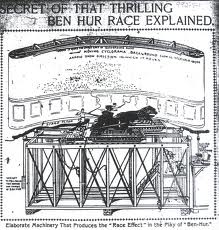

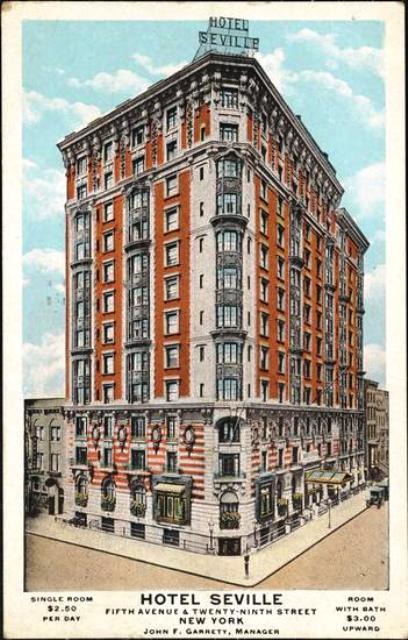

Another time, when Mrs. Pat and Pinky were staying at the Hotel Seville, the tiny dog swallowed a grape seed. The renowned Dr. Martin J. Potter of the Ben-Hur Stables was summoned to the hotel to perform minor surgery on the dog. Dr. Potter obviously had a good sense of humor (or was mean-spirited, depending on your point of view), because he told Mrs. Pat:

“I was called upon in a similar case only a few days ago. I operated on one of the elephants at Luna Park, and found that the pain was caused by overindulging in peanuts. The operation was successful from a scientific point of view, but the elephant died next day.”

This proclamation sent Mrs. Pat into hysterics, but Dr. Potter quickly assured her that the elephant would have survived had it followed the advice of the attending nurse. Pinky Panky Poo spent his recovery time on a silken couch in a special suite at the hotel with a trained nurse in constant attendance. Dr. Potter said it would not do him well to get excited, and thus, banished Mrs. Pat from the room until the dog had completely recovered.

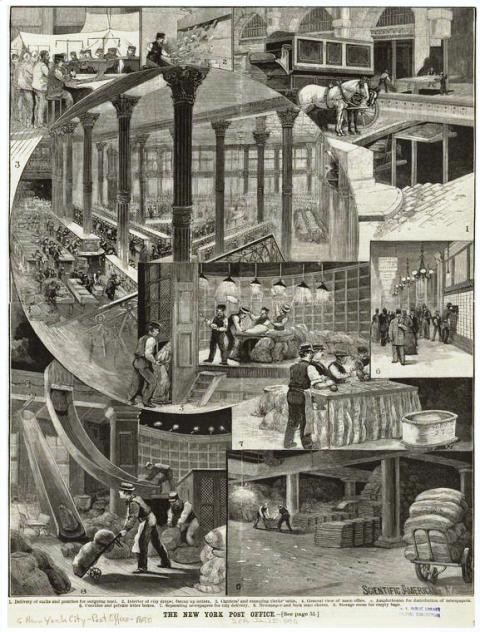

The Doggie Check Room: A Modern Exigency

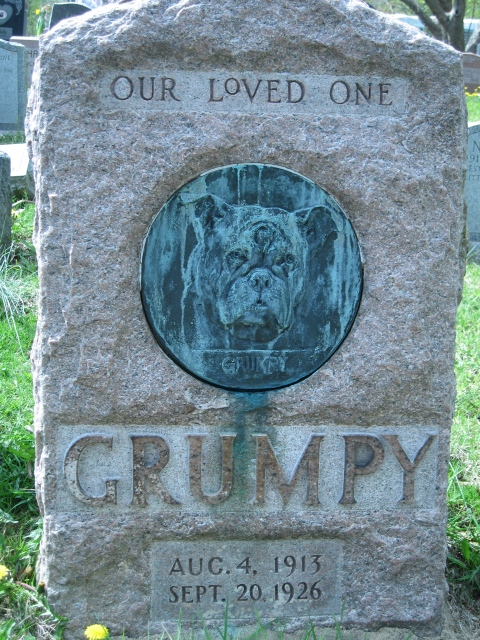

So if it weren’t for Pinky Panky Poo, the tiny Poms and Yorkshire Terriers and other canine guests who accompanied the high-society ladies at afternoon tea may not have been welcome at all. But as it was, Fred Sterry had let the cat out of the bag, so to speak, and thus had to find a quick solution to the delicate situation. Thus, a check room for dogs was established at the hotel.

According to The New York Times, the doggie check room was located in the main corridor of the hotel. A young man named Sammy who worked in the Plaza’s livery was put in charge as canine custodian.

Even though Sammy was quite young, he was “so careful with the dogs…that no owner need fear Fifi is exchanged for Fido or that her ruby spaniel has been mixed with a bat-eared bulldog from Paris. He knew when to separate the bull dogs from the Pomeranians, and he knew that an actress’s King Charles spaniel had to be held aloof from the patrician Yorkshire of the society leader.”

The plan for making the check room work was as follows:

A richly gowned woman, ladled with sables and holding a small dog under her arms, starts for the tea room. The Secret Service recognizes that the furry mass is a dog, and not part of her attire. A courteous bellboy approaches the woman with a bow. “I shall check the dog for you,” he says. “Where?” the lady demands. “We have a check room on this floor for the dogs. They will be safe and comfortable.” The woman usually goes along to make sure her pet is going to be comfortable. When she sees the smile on Sammy’s face, she is put at ease.

“It was necessary to provide a place for the transient dogs,” Mr. Sterry told the Times. “We simply couldn’t have them running about, and how we realize how deeply attached their mistresses are to them, we have opened a check room. The boy is careful, and the dogs have bits of carpet on which to lie down. It is so much the fashion for smart women to take their dogs to tea that we have been obliged to make the afternoon comfortable for them. It is simply a case of meeting a modern exigency.”

Pinky Two and Woosh-Woosh

Sometime around 1909 or 1910, Pinky Panky Poo died, reportedly after consuming some flea powder. In October 1911, the Brooklyn Daily Star reported that Mrs. Pat had a new dog named Pinky Panky Poo Two.

Mrs. Pat returned to New York in the fall of 1931, this time to perform as Countess Polaki in Edouard Bourdet’s comedy “The Sex Fable” at Henry Miller’s Theater. On this visit, she was accompanied by a rare Pekingese known as the Chinese chinchilla breed.

The dog was called – I’m not making this up — Wung-Wung Wah-Wah Woosh-Woosh Wish-Wish Bang (he was known more affectionately as Woosh Woosh Wishwoosh). The dog had been left to her in the will of Mrs. Benjamin S. Guinness, a popular New York hostess and intimate friend of Mrs. John Jacob Astor.

Mrs. Pat described the dog:

“She’s pure Chinese. She has feathers on her toes and the most marvelous lingerie. There’s nobody like her in the world. She’s almost as nice as Pinky Panky Poo, my famous griffon.”

Mrs. Pat was finally reunited with her beloved Pinky Panky Poo when she passed away on April 9, 1940 in Pau, France, at the age of 75.

An Aside

In her memoir, My Life and Some Letters, Mrs. Pat speaks of her impressions of New York: “As everyone knows, New York is built upon a rock. During this visit of mine they were constructing the subway, and every inch of the tunnel had to blasted with dynamite. The din of New York—the rush, the tall buildings, and the strange-coloured people; Italians, Russians, Chinese–all sorts everywhere–the noise of the elevators, the nasal twang–black boys, bell boys, and the noise of the street cars–I do not want to be unkind, but to me it was demoniacal.”