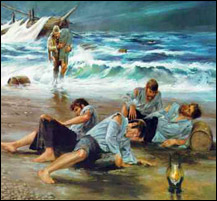

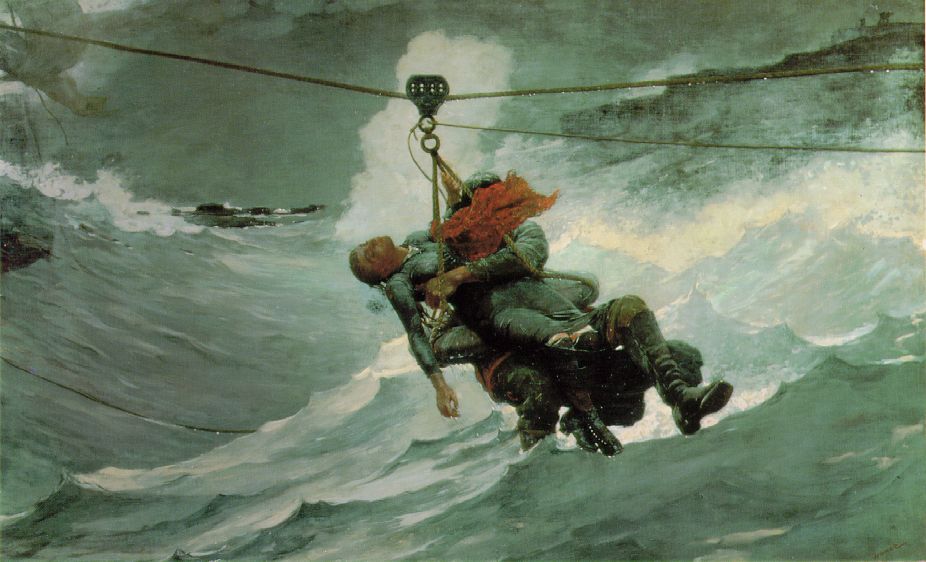

“Here are people who have been on the ocean for a week at least, no land seen, and nothing seen on the coast yet but the red light on shore, in trouble now, in danger of their lives, and here comes a man from the unseen world, in a pair of short canvas trousers, riding on a rope, to tell them of the succor near and bid them be of good heart.”– William Drysdale on the U.S. Life-Saving Services, November 16, 1890.

On July 28, 1988, President Ronald Reagan spoke to representatives from the Future Farmers of America in Room 450 of the Old Executive Office Building. About five minutes into his speech, Reagan told his audience, “There seems to be an increasing awareness of something we Americans have known for some time: that the 10 most dangerous words in the English language are, ‘Hi, I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help.’” (Cue laughter.)

The anti-government, anti-socialist, pro-market politicians may be having a field day with this famous quote today. But for more than 177,000 people who were rescued by the U.S. Life-Saving Services between 1871 and 1915, those 10 words were a gift from the heavens above.

The U.S. Life-Saving Services – a forerunner to the U.S. Coast Guard — was established by Congress in 1871 in response to the high loss of life in ship wrecks along America’s coastlines, particularly on the Atlantic coast. Not only were thousands of people killed in wrecks, but survivors often succumbed to their injuries because there was no one to help them. Many survivors also fell prey to pirates who would rob and attack them.

By 1880, the U.S. Life-Saving Services had 183 live-saving stations: 7 along the coasts of Maine and New Hampshire; 15 in Massachusetts; 37 along the coasts of Rhode Island and Long Island; 40 in New Jersey; 44 south of Cape May, N.J. and in the Gulf; 34 on the Great Lakes; and 6 along the Pacific Coast. In its ninth year of operations, the U.S Life-Saving Services responded to 250 ship disasters in which 1,854 people were rescued and only 24 lives were lost.

A Day in the Life of a Surfman

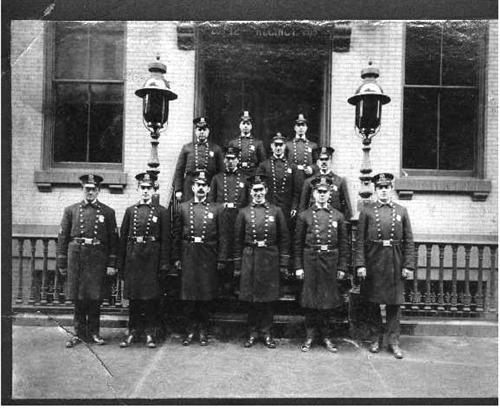

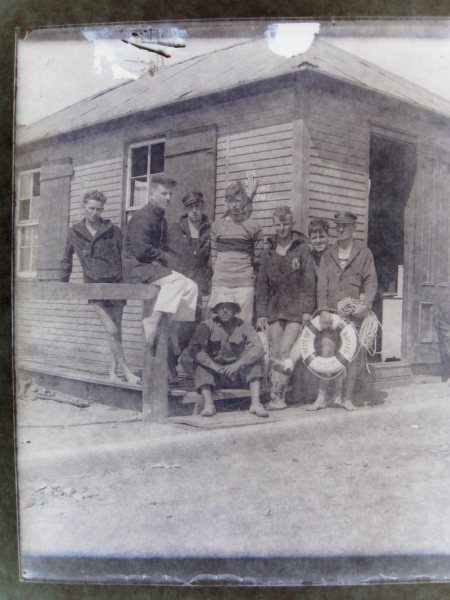

Each life-saving station was manned by a crew of surfmen who lived at the station for eight to ten months a year (usually from November to April, which was called the “active season”). Station surfmen were paid $40 a month; the keeper, also known to the men as the captain, was employed all year and paid $400.

These men of the U.S. Life-Saving Services patrolled the shores either on foot or on horseback to look for ships that were in distress or coming too close to shore. When faced with an ocean rescue situation their motto was, “You have to go out. You don’t have to come back.”

In the Spring 1992 issue of Naval History, Lieutenant Commander Robert V. Hulse of the Coast Guard vividly describes the typical duties of a surfman and his 16-year-old horse, Bill, at Blue Point Station on Fire Island. Commander Hulse worked at this station in the 1930s, shortly after the U.S. Life-Saving Services and the Revenue Cutter Service merged together to form the Coast Guard.

“Sitting atop the roof of each two-storied lifesaving station was an observation tower. There a lookout was stationed during the daylight hour to note in his log every vessel that passed. He had a pair of binoculars as well as a spyglass to aid in his observations. Once night had fallen, foot patrols would start out from each station to keep a watchful eye on any ship passing by. If we saw red and green running lights too clearly, it usually indicated that the vessel had strayed in too close to shore. If the ship kept on her present course she was bound to plow right into the outer sandbar.

In such a case you had to quickly haul a Coston flare out of your knapsack. A few seconds sufficed to twist off the outer cover and ignite the light. You held it aloft so that the reddish-orange glow would clearly be seen out at sea. The signal burned for a good five minutes. Its clear message was: “You are coming in too close to shore. Change course immediately. You are in danger.”

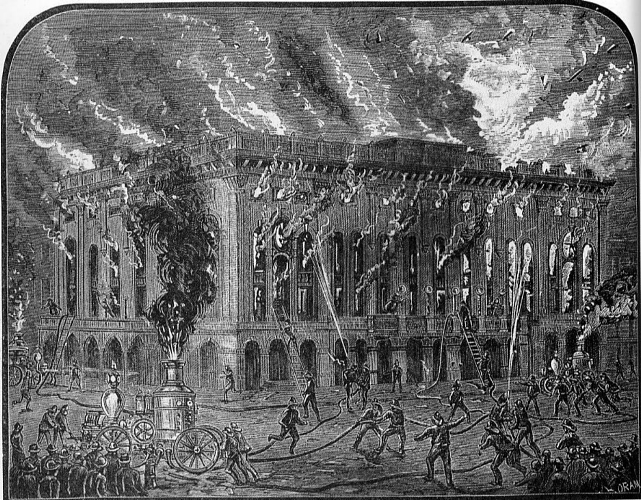

Rushing topside to the crew’s dormitory, you go from bunk to bunk to wake up your shipmates. A minute later and you are outside putting the harness over old Bill. Rolling the cart out of the boathouse is easy. Just ahead, however, is deep, loose sand, and all eight surfmen are now positioned on either side of the cart to keep it moving forward. Poor old Bill would never be able to drag it over to the water’s edge without such help. The surfboat weighs a good thousand pounds, and that’s not counting the gear.

Finally, you and your mates have drawn abreast of the shipwreck. The rescue attempt is about to begin. Captain Bennett, of course, is in total command; many lives depend on his experience and judgment.

Carefully, you help slide the surfboat off the cart into the freezing cold water swirling around your feet. Captain Bennett is studying the sea. It is he who must decide on the most propitious moment to launch. You and the others are knee-deep in the numbing cold water, steadying the surfboat whose bow is pointed straight out into that ugly, unforgiving ocean. After a split second more of appraisal, your gruff old skipper suddenly roars out, “All right, men, let’s go!”

1896: The Wreck of English Steamship Lamington

In the 19th century, the number of ships that wrecked along the beaches and sandbars of Fire Island were almost countless. Raging gales drove ships of every type and nation onto the outer bar, some never to return to the sea again.

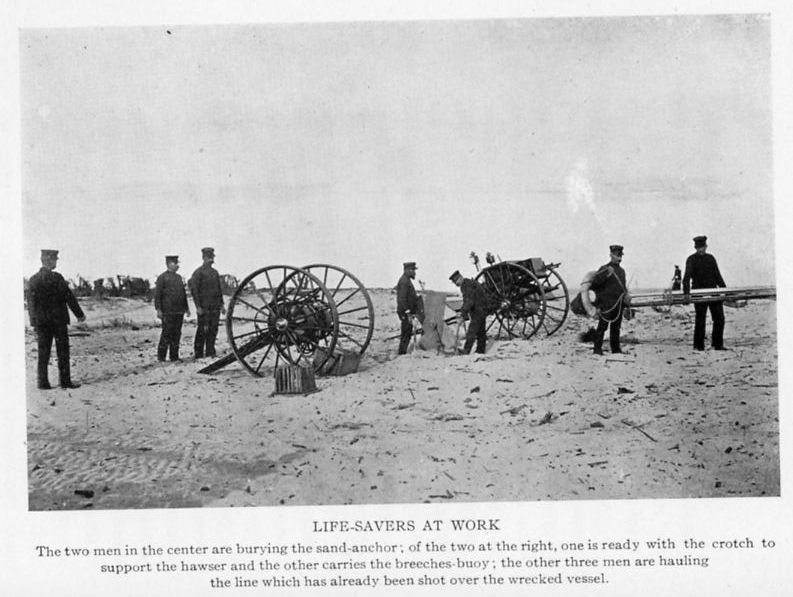

On February 4, 1896, the English steamship Lamington, with a cargo of fruit from Valencia, Spain, forged at full speed through the dense fog into the sand bar of Great South Beach, two miles east of the Blue Point Life Saving Station. Jetur Rose Payne, the number-one surfman at Blue Point, saw the lights of the ship at 8 p.m. as he was returning from the sundown patrol. The ship was moving too fast, though, and it crashed before he could warn the ship’s captain. Payne ran to the station and notified Captain Frank Rorke and the crew. A telephone message was also sent for assistance to the Bellport, Long Hill, and Patchogue stations.

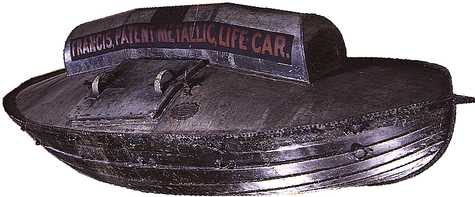

Launching a lifeboat was out of the question, so the crew used a Lyle gun to fire a line about 150 yards to the ship in distress. The first sailor to be rescued by the breeches buoy was 16-year-old Jimmie Holbrook. One by one, 17 more crew members were brought ashore, including James Brady of Buffalo, New York, who paid his way home from London by working on the ship.

The crews worked for almost 48 hours trying to rescue the remaining crew on board, including Captain G.W. Duff, the master of the freighter, the chief officer, and three engineers. Two days after the wreck, the newspapers reported that the men were still on board the doomed ship. Tremendous breakers were making rescue impossible, and it was feared all six men would perish as the ship continued to fall apart in the turbulent seas.

As it was, all of the crew survived, albeit, Captain Rorke and his life-saving crew had to make two more rescues in the following weeks to save some wreckers and engineers of a wrecking corps that were trying to salvage the steamer.

A Cat and Dog Are Rescued

In addition to the 18 rescued sailors, several animals were also onboard the Lamington. A large cat weighing 18 pounds, which had been the sailors’ pet, was carried ashore by one of the sailors on the breeches buoy (I’d love to see them try this with my cat). The cat was presented to Harrison Craig Dare, a newspaper editor from Patchogue, Long Island. A terrier was also rescued via the breeches buoy and given to Frank Soper of Ocean Beach, Fire Island.

Four Trick Ponies Are Lost

On board were four trained ponies that were being transported from Spain to Jose Aymor of the Cambridge Hotel in New York. (There had been five, but one died shortly before the ship struck the sand bar.) Unfortunately, all four ponies drowned two days after the ship crashed into the sandbar.

Life-Saving Stations of the Long Island Coast

In the late 19th century, there were 30 life-saving stations scattered along the Long Island Coast from Montauk Point to Rockaway Point. The following is a list of those stations and the keepers in about 1880:

Ditch Plain, William B. Miller

Hither Plain, William D. Parsons

Napeague, John S. Edwards

Amagansett, Jesse B. Edwards

Georgica, Nathaniel Dominy

Mecox, John W. Hedges

Southampton, Nelson Burnett

Shinnecock, Alanson G. Penny

Tiana, John E. Carter

Quogue, Charles H. Herman

Potunk, Isaac Gildersleeve.

Moriches, Gilbert H. Seaman

Forge River, Ira G. Ketcham

Smith’s Point, John Penny

Bellport, Henry Kremer

Blue Point, Frank Rorke

Lone Hill, George E. Stoddard

Point O’ Woods, William H. Miller

Fire Island, J.T. Doxsee

Oak Island, Edgar Freese

Gilgo, William E. Austin

Jones Beach, Steven Austin

Zach’s Inlet, Philip K. Chichester

Short Beach, John Edwards

Point Lookout, Andrew Rhode

Long Beach, Richard Van Wicklen

Rockaway, William Rhinehart

Rockaway Point, Daniel B. Abrams (today this is Beach 129th Street)

Eatons Neck, Henry E. Ketcham

Rocky Point, Harvey S. Brown

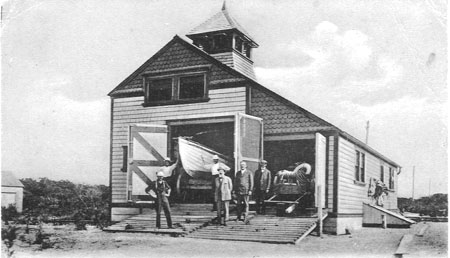

U.S Life-Saving Services Station #22, Third District: Blue Point

The Blue Point Life-Saving Station, constructed in 1856, was located on the beach of Great South Bay near the community of Water Island (about 10 miles east of the Fire Island Lighthouse and about 4 miles south of Patchogue). In its first year of operation, Charles R. Smith was appointed keeper.

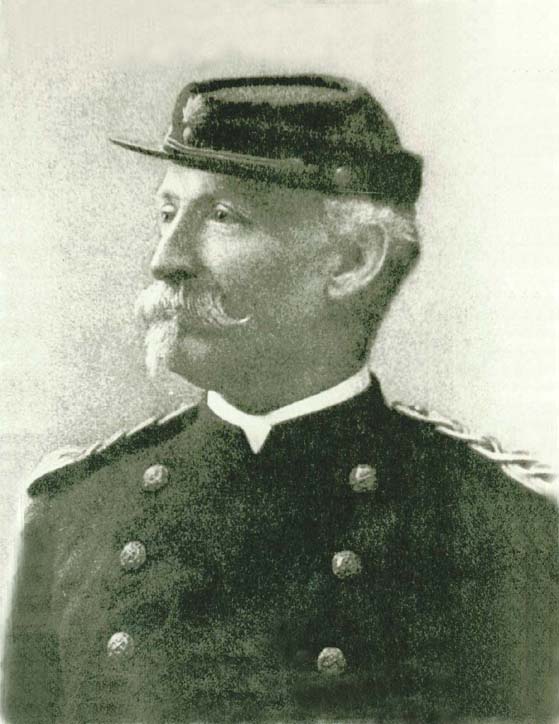

In 1896, when the wreck of the Lamington took place, Frank Rorke was the keeper. Rorke was appointed to this position on July 5, 1887, and remained at Blue Point until his retirement with thirty years of service on May 31, 1919. Although the U.S. Life-Saving Services merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the U.S. Coast Guard in 1915, Blue Point stayed in operation until 1937.

The End of an Era

The era of rescuing shipwrecked sailors by surfboat and breeches buoy ended in 1915, when the U.S. Life-Saving Services merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to create the U.S. Coast Guard. Some of the old stations, however, continued to be manned by surfmen who helped rescue mariners until the end of World War II. Improvements in navigation, radar, sonar, and the helicopter combined to render these stations obsolete. Unfortunately, most of them were sold at auction or torn down.

The good news though, is that while the U.S. Life-Saving Services only existed as a separate entity for 44 years, during that time the brave surfmen and their horses came to the rescue of 178,741 men, women, and children — 177,286 of whom were saved. That’s an outstanding record, considering the limited equipment they had.

If you enjoyed this story, you may like reading about Tim, the shipwrecked cat rescued by the men of the Eatons Neck Life-Saving Station on Fire Island.