In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States government allocated funds to feed hundreds of cats that were “hired” to catch rats at post offices and other federal buildings.

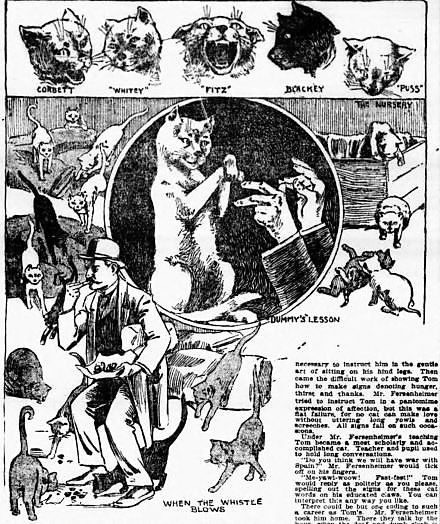

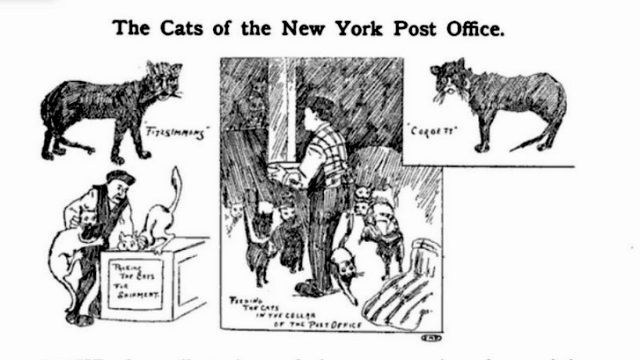

New York City’s Post Office cats were featured in a news article in 1898

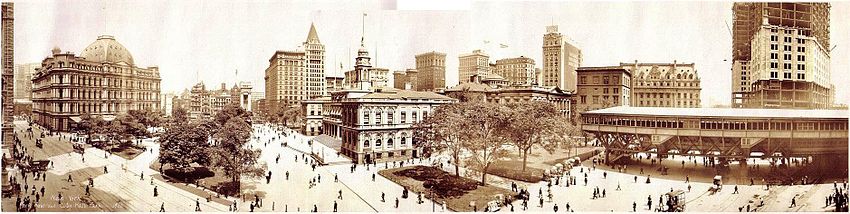

On November 5, 1904, New York City postal clerk George W. Cook celebrated his 54th anniversary working for the U.S. Post Office Department with a special dinner. The banquet took place at 2 p.m. in the basement of the General Post Office building, also known as the Mullet Post Office, which was then located at the intersection of Broadway and Park Row in New York’s City Hall Park.

The menu was simple, and included raw calves’ liver and lambs’ kidney heaped high in four piles and served on clean white paper. In attendance were George, two “boss” sergeant cats named Bill and Richard, one bow-legged, brindled Roundsman cat, and 57 patrol cats.

The entire dinner was funded by the United States government.

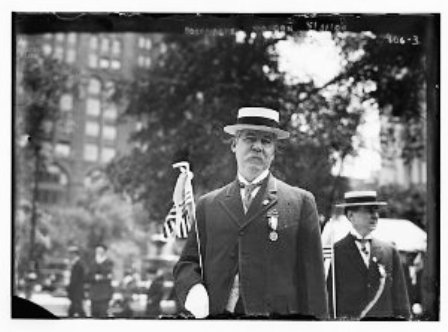

George Cook’s 54 years of service topped that of Acting Postmaster Edward M. Morgan, shown here, who had 45 years with the Post Office in 1904.

Superintendent of Federal Cats

When he wasn’t sorting letters in the Mailing Department, 81-year-old George Cook was also (unofficially) the Superintendent of Federal Cats. Under Postmaster Edward Morgan, it was George’s responsibility to feed the almost 100 New York mousers who were “employed” by the U.S. Post Office Department to kill the rats that were attracted to the glue used on envelopes and packages.

George was provided a budget of about $5 a month — allocated through the department’s Salaries and Allowance Division — which he used to purchase cat’s meat from a restaurant on Ann Street. The budget allowed for one meal a day. (George told reporters he thought the budget should have been at least $10 a month in order to accommodate his growing feline police force.) The budget was reportedly necessary: Many of the cats had become lazy and started nibbling on leather mail bags and stealing postal clerks’ lunches, so the meat kept those bad habits at bay.

The Mother of New York Postal Cats

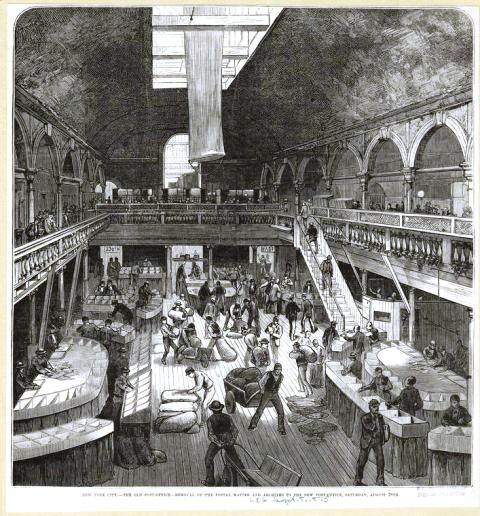

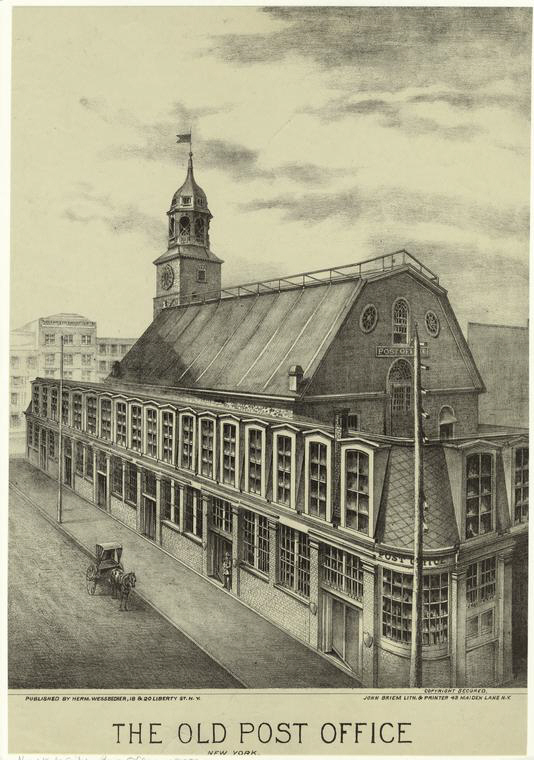

On the evening of August 28, 1875, the transfer from the old post office building on Nassau Street to the new building in City Hall Park commenced. One of the items included in the transfer of property and effects was a female tabby mouser. New York Public Library Digital Collections

George Cook, a father of five daughters (Carrie, Jennie, Lilly, Laura, and Annie) and a resident of Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side, began working for the Post Office Department in 1850, when New York’s general post office was located in the former Middle Dutch Reformed Church on the corner of Liberty and Nassau streets. When the new General Post Office at City Hall Park opened in August 1875, George brought one postal tabby with him and put her to work as the new building’s first rat catcher.

“That darned low critter would never stay on post,” George told several New York reporters during his grand anniversary dinner. “She used to go a stravagin’ all over town. I tell you, mister, in a few months there were more cats in this office than letters. Every corner I turned it seemed as if I stumbled on a nest o’ kittens.”

According to George, one day the Superintendent of Mails asked him to get six strong mail bags. “He just stuffed them bags full o’ big and little cats and registered them, yes, mister, an’ sent ‘em to a little post office in New Jersey. Gosh! I wonder what the feller said when he got ‘em.”

Built in 1729, the Dutch Church on Nassau Street was used as a house of worship until 1776, when British troops converted the 100 x 70 foot building into a military prison and riding school. Worship services resumed in 1790 until the United States government stepped in to lease the property for a post office in 1844. Incidentally, Benjamin Franklin conducted experiments with lightning from the belfry in 1750.

As you can guess, transferring a few cats across the river did not solve the problem. By 1897, there were about 60 cats in the New York Post Office (I’m sure it was one of these cats that took a ride through the pneumatic mail tubes in October 1897). Most of them were born in the building, but others came from the restaurants on Park Row or gave up catching sparrows in City Hall Park for a more secure job on the feline police force.

That year, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) was called in to remove about 30 of the 60 cats and have them “humanely” destroyed. Some of the cats taken away included Fitzsimmons, a long-legged cat who could stand on his hind legs, and Tim McCarthy, a big grey cat who was a known lady-killer. Those cats spared from the SPCA’s wagon included Nellie, a champion mouser and Jim Corbett, a large black and white cat.

Of course, the surviving cats continued to breed, so every so often the post office allowed human employees to take their favorite cats home when the ranks were full. Unfortunately, the SPCA also continued to raid the cat colony when things got out of hand. The old cats that were born in the building knew to stay away from the cat catchers. But the kittens and the cats from the restaurants, which were used to being petted, were often captured and taken away to the death chamber.

If the population really got out of control, the postal clerks would “mail” some cats in the newspaper mail sacks. The sacks would then be carefully placed on the wagon with the other mail and quietly deposited at some other sub-station. (Occasionally, a cat would accidentally get into a mail bag and be delivered to a distant city if the railway post office clerks didn’t intercept.)

The Newspaper and Registry Cats

Second-class cats that worked in the newspaper department could be promoted to first-class cats in the Registry Division on the top floor.

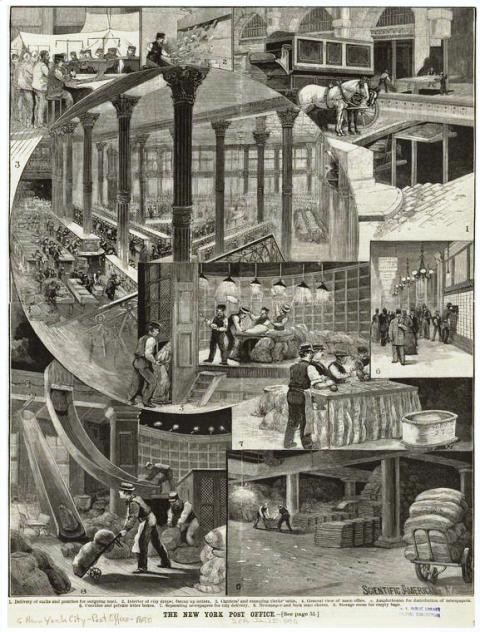

At the General Post Office building in New York, most of the cats started their policing careers at the ground level, or more specifically, the newspaper department. This department, which was responsible for sorting and distributing newspaper mail (second class) and mail from the ocean steamships, took up the entire basement of the enormous building.

The basement offered numerous patrol and napping posts for the cats, including 700 closets where the employees stored their street clothes and a large storage area for all the U.S. mail bags not in use. Each patrol cat had a favorite spot to sit for hours and wait for a rat to pass by.

Hard-working cats that went above and beyond the call of duty could be promoted to the Registry Division on the top floor of the building. Registered mail required extra care to safeguard it, and all persons handling this mail had to account for it as it passed through their hands along its route. The postal cats had to be extra diligent in their rat-catching efforts to protect this valuable class of mail.

This 1890 engraving from Scientific American depicts the many departments of the General Post Office, including the large area in the basement dedicated to the distribution of newspapers (circular image) and the newspaper and bulk mail chutes (bottom left). I wonder how many curious cats went down those chutes? New York Public Library Digital Collections

George said he used what he called “a two-platoon system” in order to ensure there were always enough cats on duty at one time to catch the rats and mice. He said he set up this system one day when he didn’t have enough cats on reserve to handle a massive rat attack. Apparently a cheese house had mailed samples of its most powerful Limburger cheese, and the mail bags were attacked by the rats. A riot ensued, and there were not enough cats on duty to arrest all of the perpetrators.

The Daily Lunch Hour and Furlough

Every day at around 2 p.m., George, like the Pied Piper, would blow a whistle to summon the second-class cats to their lunch. Cats would come running to the feeding area near the lockers from every corner where they were mousing (or sleeping on the job). They’d scramble under and over hand trucks, through people’s legs, over counters, or whatever they had to do to get to the food the fastest.

The cats ate in “assigned” groups of six, and if a cat from another table went to the wrong place by mistake, the boss of the group would box his ears and chase him back to where he belonged. In addition to strips of meat (usually lamb, beef, or calf livers and hearts), sometimes the cats would get fresh catnip for desert or some green grass from outdoors.

Postal laborer William Dixon helps feed the cats, most of whom ran away when the flash fired on the camera. The New York Press, September 11, 1910

In order to keep the second-class and first-class cats separate so they wouldn’t fight, George would serve the top-floor cats separately. All those cats detailed for duty in the Registry Department would gather around the elevator door at the designated hour and take it down to the basement. When they were done eating, they’d take the elevator back up to work. (I am not making this up.)

In the summer months, the newspaper department cats were allowed to take an afternoon break outdoors in City Hall Park. They’d catch some sparrows, or maybe swap stories while soaking up the sun with the park cats or with Old Tom, the official cat mascot of City Hall. (Naturally, the park cats wanted to win a job at the post office, so they were on their best behavior with the postal cats.)

After sunning themselves, the post office cats would stroll back to the basement and resume their duties.

A view of City Hall, Park Row and City Hall Park in 1911. The General Post Office is on the left.

“Please Adopt Our First-Class Cats”

On December 10, 1906, an article in the New York Herald reported that due to overpopulation, the post office was going to have to lay off some employees in the “Department of Mouse Catching.” The public was invited to come to the post office to adopt some first-class cats. According to the article, some of the cats were descendants of the original tabby from the Nassau Street post office. “Never was a greater variety of breeds under one roof than that which may be found in the basement of the Post Office,” it stated.

The New King of the Cats

In the spring of 1910, Policeman John Foley, shown here, told a reporter for the New York Press that a black and white cat named Mollie (also shown here) was at the head of the Civil Service list. Her specialty was hunting sparrows by hiding under newspapers, and she held the record with two in an hour and 12 in a week.

By 1910, there were about 200 cats on Uncle Sam’s payroll in New York City. Most of these felines worked for the Post Office Department — nearly 100 in the General Post Office building and the rest at the various sub-stations.

In 1910, 87-year-old George Cook was living with his daughter, Carrie, her husband, James E. Walker, and their son, Fred, in a brand-new townhouse at 177 Rogers Avenue in Brooklyn, shown here.

Although George Cook was still working as a clerk, a much younger man named William W. Dixon was now in charge of the cat police force. Dixon was making $700 a year as a laborer, but one of his primary duties was caring for the mousers. His fellow employees called him “King of the Cats.”

One of the people who kept in contact with William was Policeman John Foley of the City Hall Park police. Policeman Foley looked out for the park cats, and he would always try to persuade William to take one of them whenever there was an opening on the United States postal force.

By 1910, construction of a new General Post Office on 8th Avenue (31st to 33rd Street) had already begun. In that year, 87-year-old George Cook was a widower, but he still listed his occupation as “postal clerk” on the 1910 Census report.

Postal services continued on the first floor of the Mullet Post Office through the 1920s, but the building was demolished in 1938 as part of the city’s efforts to beautify the city for the 1939 World’s Fair. I could find no mention of New York’s post office cats after 1924, so one might assume their skills were no longer required in the brand-new building.

[…] 1904: The Feline Police Squad of New York’s General Post Office […]

[…] 1904: The Feline Police Squad of New York’s General Post Office […]

[…] U.S. had actually allocated about $5 per month to feed and shelter cats for the purpose of keeping vermin out of the post offices. George […]

Splendid! I will be linking to this post in an upcoming one I am doing on Old Tom in the Washington Post Office!

Glad you enjoyed it — it’s one of my favorite cats-in-NYC history! I look forward to reading about Old Tom.

[…] this splendid blogging colleague, The Hatching Cat, (I subscribed immediately) wherein his post, 1904: The Feline Police Society he outlines the fascinating society specifically of the New York post office cat force. It is a […]

[…] church constructed a parsonage on the site, which served as a residence for the minister of the Middle Dutch Church on Nassau Street between Cedar and Liberty […]