“Then all of a sudden I strikes water and opens my eyes. I was flying through the air, and before I comes down I had a fine view of the city.”–Joralemon Street Tunnel worker Richard Creeden, March 27, 1905

The following story is about a little kitten who arrived at the Joralemon Street Tunnel in Brooklyn at the same moment a miracle took place.

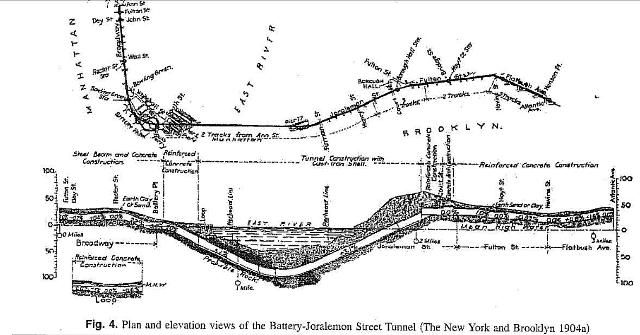

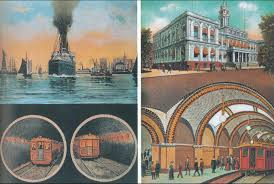

In May 1900, a committee of 50 Brooklyn men appeared before New York’s Rapid Transit Commission to advocate for a full extension of the subway system to Brooklyn. The committee suggested a route that would extend down Broadway to the Battery in Manhattan, go under the East River and Joralemon Street in Brooklyn, past Borough Hall, up Fulton Street to Flatbush Avenue, and then to the Long Island Railroad Station at the junction of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues.

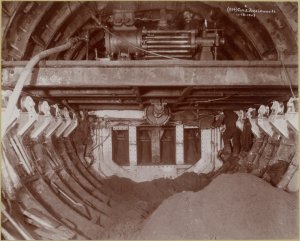

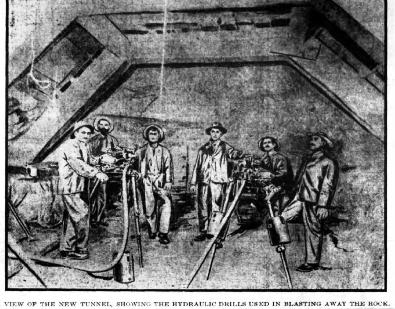

On July 24, 1902, the contract to build this extension was awarded to the Rapid Transit Construction Company. Work on the first underwater tunnels between Manhattan and Brooklyn took place between 1903 and 1907, starting simultaneously from excavated shafts at South Ferry on the Manhattan side and at Henry Street in Brooklyn.

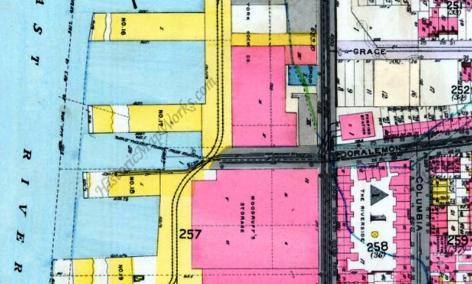

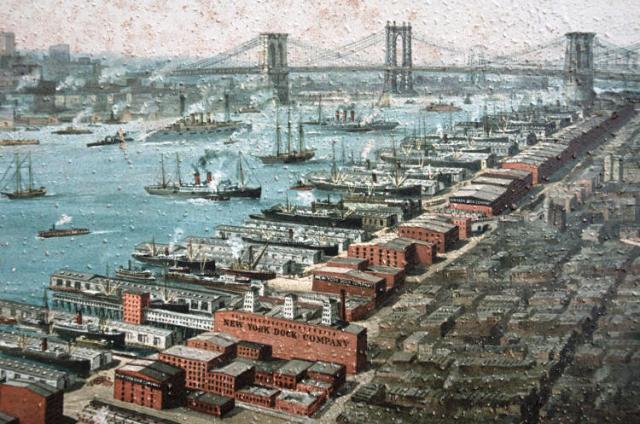

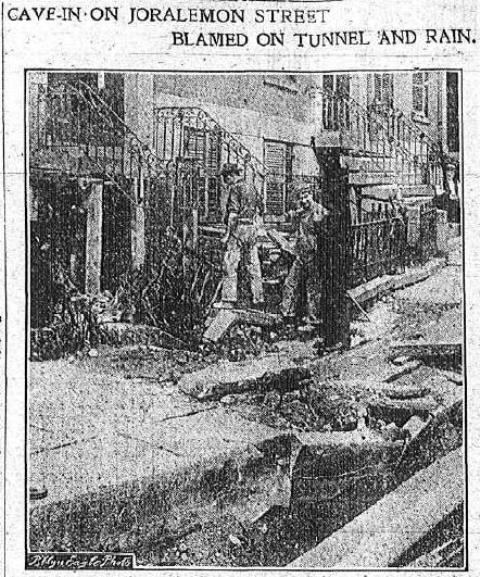

By March 1905, the excavation work on the Brooklyn end of the tunnels had reached just beyond Piers 17 and 18, then owned by the New York Dock Company. For Richard Ambrose Creeden, a 25-year-old tunnel worker from Jersey City, it was a very good thing that the excavation work had already cleared the long wooden docks by this time.

Monday Morning, March 27, 1905

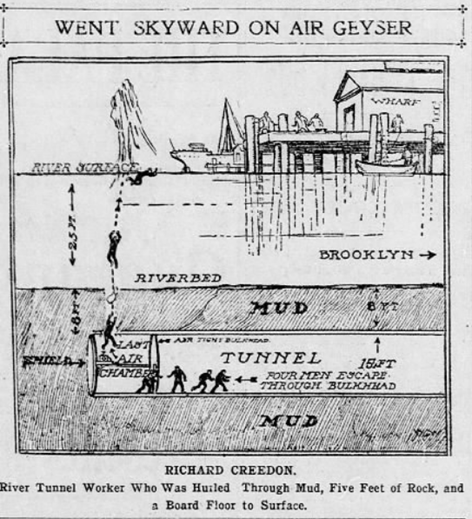

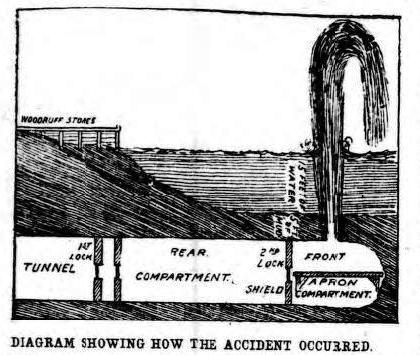

At about 8 o’clock on March 27, Richard and Jack Sheehy were on the apron, a platform for the workers to help them reach the top of the mechanical shield. Three other laborers — John Hayes of Manhattan, John Bridey of Hoboken, and John Egan of Jersey City — were also working in the north tunnel air chamber on the Brooklyn side.

Richard, described as a “small, pale, wiry Irishman” with blue eyes and brown hair, noticed a small fissure at the top of the tunnel. He immediately ran to the pile of bags filled with sawdust and shouted out a warning to his fellow workers. Then he climbed a ladder and attempted to push the bags against the widening aperture as the air pressure continued to build.

Up to this point, Richard Creeden had not much luck in his life. Born August 27, 1880, in Jersey City, he was the fourth child of Bridget Welsh Creeden and John Creeden, both Irish immigrants. He had two older sisters, Maggie and Mary, and one older brother, Cornelius. His father supported the large family by working as a laborer. By 1895, Richard and his mother were the only surviving members of the family.

According to census records, Mary died on October 11, 1884, when she was just eight years old. Cornelius died just two weeks later on October 29 at the age of six. (The cause of death is unknown, but the fact that two young children died just weeks apart leads me to believe that they succumbed to either an illness or an accident.) Then on April 26, 1890, when Richard was only 10 years old, his 20-year-old sister Margaret passed away. His father passed sometime before 1895 and his mother had also died before March 1905.

The Joralemon Street Tunnel Miracle

As the pressure in the tunnel increased, Richard was pinned to the roof of the tunnel. Within seconds the roofing and earth gave way, creating a four-foot-wide hole. He was pushed through the hole and into the earthen riverbed, where he had to struggle with shoring timbers while choking on mud and stones. With the air keeping the water back, and Richard’s body blocking the hole like a cork, the other workers were able to escape the tunnel.

Finally, the pressure propelled Richard like a rocket completely through the 17 feet of river-bed silt and 10 feet of water. Witnesses on the docks said they saw the two bags come out, followed by a geyser of water and then Richard. They said he shot up about 20 feet, “performing acrobatics” in the air for a few seconds before falling into the water.

Following his amazing flight through the air, Richard came to rest just beyond the Floating Bethel, a former Erie Canal boat that had been converted into a place of worship for sailors, and which had been moored at Pier 18 since 1893. Although he was wearing heavy clothes and boots, he was a good swimmer and was able to stay afloat while awaiting rescue from a policeman and some men on a boat.

Freezing cold, Richard made his way to the “sandhouse” (engine room and storeroom) at the corner of Furman and Joralemon, where he was attended to by a surgeon from the Long Island College Hospital. There, he joked with the press, stating that he had just asked the boss for a raise that day, but he didn’t expect it to come so quick.

Although he refused to go to the hospital, Richard reportedly asked to smoke his pipe before a carriage took him to the home he shared with his aunt, Mrs. Ellen Driscoll, of 611 Henderson Avenue (today’s Marin Boulevard) in Jersey City. He asked to return to work the next day, but he spent several days at home recovering from shock.

Bright Eyes Moves Into the Tunnel

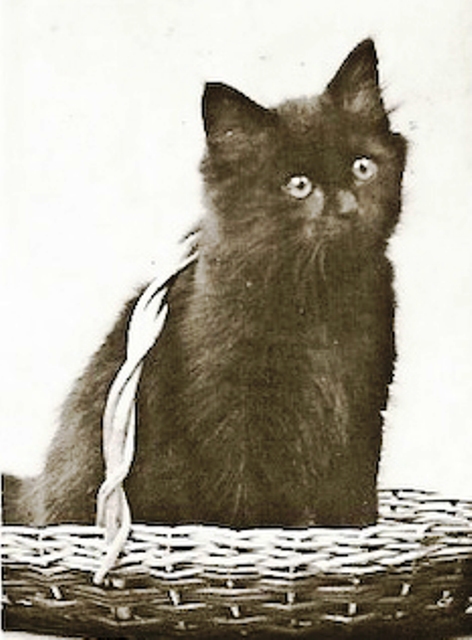

According to a story in the Brooklyn Daily Standard Union on May 14, 1905, it was while Richard was smoking his pipe that Bright Eyes first made his appearance at the Joralemon Street Tunnel.

The tiny black kitten, about three months old, peered 60 feet down the shaft and decided to go exploring. The workmen tried shooing him away, “But, law sakes!” as one workman noted, “dat coon kitten jist cocks his tail and keeps agwine down.”

Several workmen who were going down into the tunnel on the “elevator” cage also tried to give the kitten the boot, but he simply jumped into the cage and gave a farewell meow to the world above. The tunnelers agreed to adopt the kitten, believing the cat brought good-luck to the five men who miraculously survived the blowout.

No one knew where the brave little kitten came from, but the fact that he was well groomed led the men to believe that he had been living the good life in Brooklyn Heights. He seemed to take very well to tunnel life, and for about eight months, until Nellie the Subway Dog appeared, Bright Eyes was the only mascot of the tunnel workers. The cat took his job as mascot very seriously, especially when it came to begging for his portions of the workers’ food rations.

Two months after what most would consider a life-changing event, Richard sued his company for $26,000 in damages, claiming he had not been able to work since the accident occurred. However, he did eventually get back to work; on a draft registration card for World War I, he claimed to be working as a pipe fitter for P. McGovern & Contractor (the contractor for the 60th Street tunnel) and living at 1126 Third Avenue in Manhattan.

From New York he moved to Detroit, where he worked as a laborer in the compressed air industry in the 1920s and 1930s. When he registered for the draft for World War II at the age of 61, he was retired and living in San Francisco.

I guess one could say he found the light at the end of the tunnel.

[…] 1905: Bright Eyes, the Kitten Mascot of the Joralemon Street Tunnel […]