In Part I of this Old New York cat story, we met Dr. Hale, the superintendent of Brooklyn’s public baths who was arrested and charged with uncleanliness — that is, for having a messy house filled with way too many cats. In Part II, I’ll tell you why the fur was flying at 40 First Place after Dr. William Henry Hale placed an anonymous “cats for sale” ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1908.

We’ll also explore a brief history of the Brooklyn public baths. This is, after all, a blog that explores the history of New York City.

Overburdened by Cats in Brooklyn

In 1908, Dr. Hale placed an anonymous ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as follows:

$50 reward will be paid for satisfactory homes for twenty-five cats; or $2 for each cat separately. Address OVERBURDENED, Box 24, Eagle office.

Unfortunately, the ad backfired. I guess you can say Dr. Hall took a bath on the ad that he placed.

You see, Dr. Hale failed to tell his wife, Louisa, that he had placed the ad. Big mistake And although he asked the newspaper to keep it anonymous, a curious reporter did some investigating and found out that Dr. Hale–who was reportedly one of the most famous residents of Carroll Gardens–had placed the ad.

The reporter went to the Hale house and interviewed a very angry Mrs. Hale.

“I would never let one of my cats, when I do give some away as they grow too numerous, go away with anybody until I have met the persons personally!” Mrs. Hale told the reporter. “And then think of all the visits I have to make later to see that the cats are being well cared for! Why did the doctor ever do this?

“Once I thought—before I married—that I knew all about men. Alas! I’ve only begun to find out about them since I’ve married. Oh, such a man!”

Mrs. Hale said she was worried that someone who lived in a top-floor apartment with no backyard would take the cats, or someone would make the cat sleep in a drafty back shed. She also wanted to get collars for all the cats, and it was too warm to put collars on the cats at that time.

Louisa Hale said she didn’t know how many cats she had, but she thought it would cost her husband closer to $500 than $50 to get rid of them all at $2 apiece (if you do the math, that’s 250 cats!).

The day after the story appeared, a procession of people came to the Hale’s house–not to take cats away, but to bring them additional “bedraggled and offcast cats.” Here’s what one stranger reportedly said to Dr. Hale when he answered the door:

“I saw the newspaper article about your wife. No, I don’t want any of her cats. I wouldn’t think of taking any of your money. But we have a cat we want to find a nice home for. We love it too much to let the SPCA kill it. I thought I’d bring it around and ask your wife if she didn’t want it. If she has twenty-five already one more won’t inconvenience you any, will it?”

The Fur Flies at 40 First Place

In 1909, several Health Department officers responded to the Hale’s cathouse on another complaint from a neighbor. Dr. Hale reportedly refused to allow the officers in to the house, and so, for about a half hour, the Hales and the officers exchanged shouts through the locked door. As one news account reported:

“Figuratively speaking, the fur flew in front of the home for a good half hour. The merry war was watched with intense interest by cats of all conditions. Fine maltese cats and tabby cats of high and low degree, gray, yellow, cats that had once been white, feeble old grandmother cats and playful kittens romped and frisked about the spacious courtyard, and meowed their approval whenever Dr. Hale made a particularly telling point. A few fierce-looking, battle-scarred veterans looked daggers at the inspectors, and growled ominously in a way that meant that all Dr. Hale had to do was to say ‘sic ‘em Tom!’ and they would fight tooth and nail against the enemy. In the end, the cats won. The Health Department officers went back to their cars.”

Dr. Hale, who was about 65 years old at this time, told the news reporter that he and his wife would continue to defy the Health Department until the bitter end, and that the stray tabbies would still be welcome at 40 First Place.

The Hales’ Final Years

In March 1917, which was the month that Dr. Hale was found guilty of having too many cats, Brooklyn Borough President Edward J. Riegelmann “fired” Dr. Hale by eliminating the position of Superintendent of Public Baths from the payroll. According to news reports, the ousting was not in reaction to Dr. Hale’s messy cathouse, but to an incident in which Dr. Hale was caught entering the women’s section of the Fourth Avenue bath house.

Upon losing his position with the city, Dr. Hale placed another ad in the newspaper: Member United States Supreme Court bar and New York bar wishes employment.

I’m not sure if Brooklyn’s number-one cat man ever found another job, but if he did, it didn’t last long. On May 3, 1919, Dr. Hale died at his home at 452 Prospect Avenue. His estranged wife, who was still residing on First Place, reportedly went to check on him and found him dead in his bed. He was buried in a family plot at Rural Cemetery in Albany.

Five years after Louisa Hale’s husband died, Superintendent William G. Haven and three animal control attendants from the SPCA at 33 Butler Street broke down the barricaded door at 40 First Place. There they found 18 cats, who had all been abandoned when Louisa was taken to the Kings County Hospital about 10 days prior (the Court of Special Sessions had her committed to the hospital after neighbors complained about the cats again.)

The neighbors told reporters Louisa Hale had become a recluse shortly after her husband died, and was often seen bringing cats and food into the house. They described the house as in a “deplorable state of dilapidation.”

Hundreds of neighbors, reporters, and photographers gathered around to watch as the agents made their way through the house looking for the cats. The cats were taken to the Brooklyn Pound “for further disposition.” I don’t think I want to know what that means.

A Brief History of the Brooklyn Public Baths

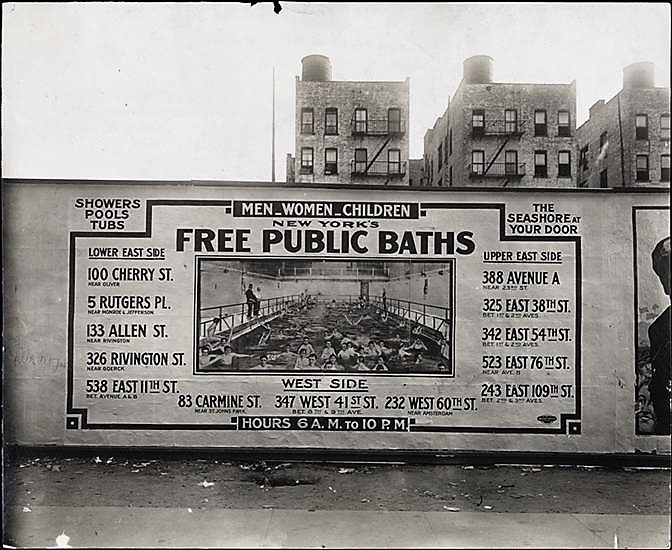

In the late 1800s, a survey found that there was only one bathtub for every 79 families living on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In response to this public health crisis, New York City introduced several city-funded bathing facilities to Manhattan and Brooklyn.

The city’s first funded bathing facility opened in March 1901 at 326 Rivington Street in Manhattan. With about 91 showers, it had provided more than 800,000 baths by the end of the following year. The city’s second and third public baths were constructed in Brooklyn.

The bath at the intersection of Hicks and Degraw Streets, which had 63 bathing units (showers and tubs), opened in September 1903. The Pitkin Avenue bath in Brownsville provided residents with another 96 bathing units when it opened a month later.

All of the public baths constructed in Brooklyn prior to 1906 (which included baths at Huron Avenue, Montrose Avenue, and Duffield Street) were designed by the Brooklyn architects Axel S. Hedman and Louis A. Voss. None of these structures are still standing. A second group of larger, more grandiose baths were constructed beginning in 1906, including the baths on Nostrand Avenue, Hamburg Avenue, and Fourth Avenue.

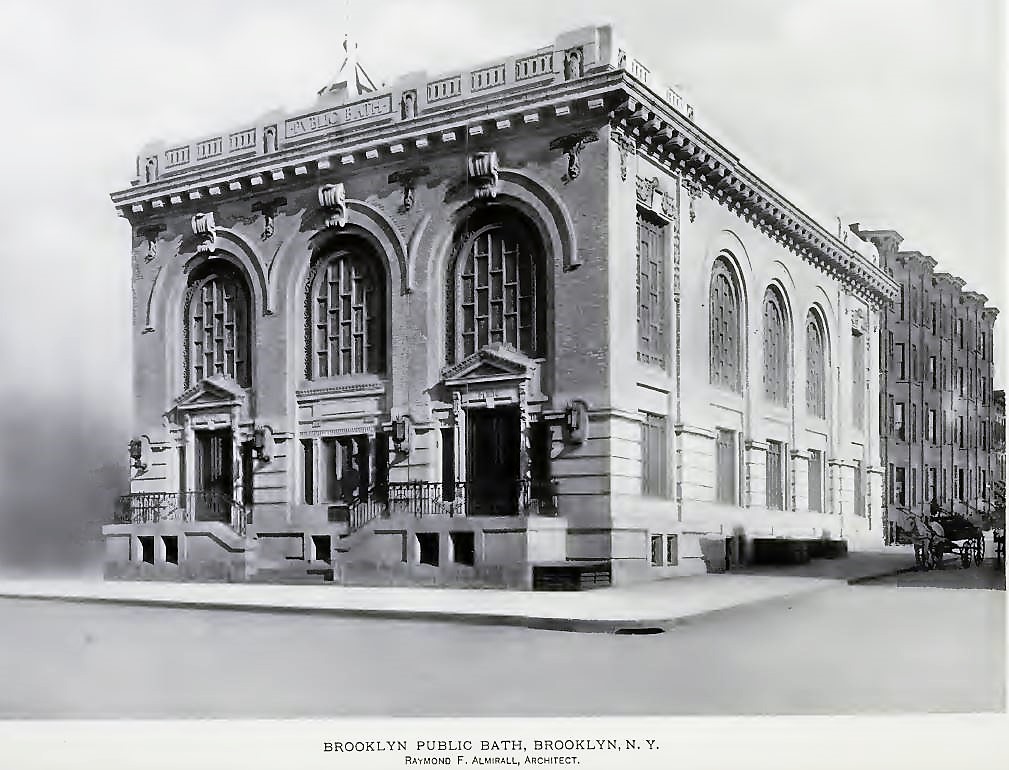

Public Bath No. 7 at 227 Fourth Avenue, which is where Dr. Hale was caught entering the women’s bathing section, was built to serve the densely populated neighborhood bordering the industrial and warehouse zone developed along the shores of the Gowanus Canal.

Described as the most ornate of Brooklyn’s public baths, No. 7 was also the first in Brooklyn to be equipped with a “plunge” or swimming pool (Dr. Hale was a huge proponent of swimming pools). It was designed by Raymond F. Almirall, a Brooklyn native and graduate of Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute and Cornell University.

Public Bath No. 7 closed for repairs in 1935 and later reopened as a gymnasium, which operated through the 1950s. The building was designated an individual landmark in 1984.

In the 1990s, the former bath house was home to a gym and a venue for concerts and events called the Lyceum. Today it is home to Blink Fitness.

Well, a sad outcome for both the Hales and the cats. Facinating story though, as always. I just wanted to say how much I enjoy the stories you dig up. I can see how much research goes into them. Thank you!

Thank you Noelle, I appreciate you responding, and I’m glad to hear that you’re enjoying my stories. I have a book coming out in the spring–all cat men stories–so you may be interested in that. I love digging up these stories and learning about so many people and places of Old New York, so it’s nice to hear when people appreciate my work.

I can’t wait for the book to come out. I’ll be buying it for sure!

I just found out that it was my great grandfather who caught Dr Hale going into the ladies bath. He was initially found to be guilty, but was later acquitted.