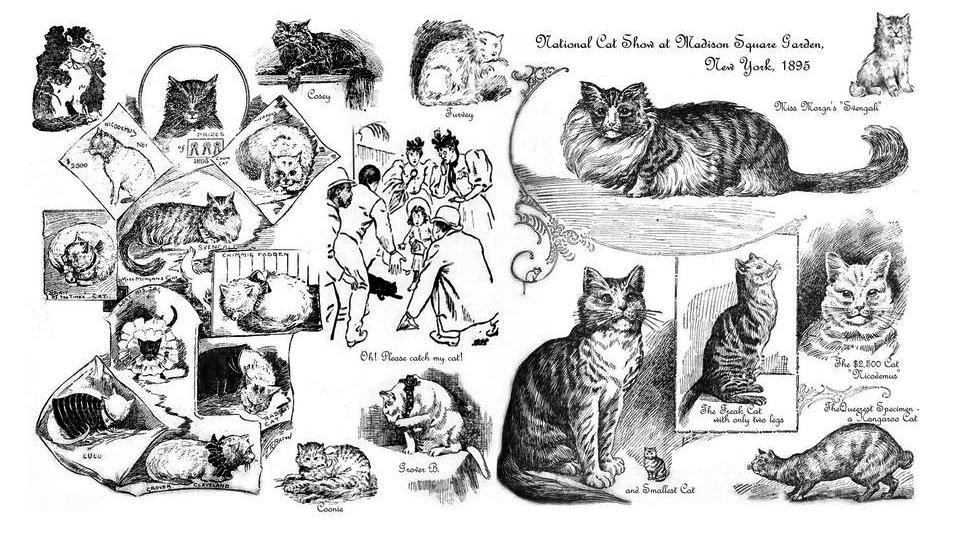

Scenes from the 1895 National Cat Show at Madison Square Garden II. One of the cats that caused the biggest stir at this show was Nicodemus, owned by New York prankster Brian G. Hughes.

Manager Bunnell stood in the center of his museum on Broadway, his hands in his hair, utterly perplexed… He was surrounded by cats in cages, cats in wooden boxes, cats in band-boxes, cats in bags, half of them yelling, spitting, and scratching, as mad as cats can be in uncomfortable quarters and in a strange place. A deep scratch on his nose… told how inexperienced he was in the ways of cats.– The New York Times, March 6, 1881

Although the first National Cat Show at Madison Square Garden II in May 1895 is often cited as the first cat show in America, there were actually quite a few cat shows in New York City and other American cities before this “official cat show” took place at the Garden.

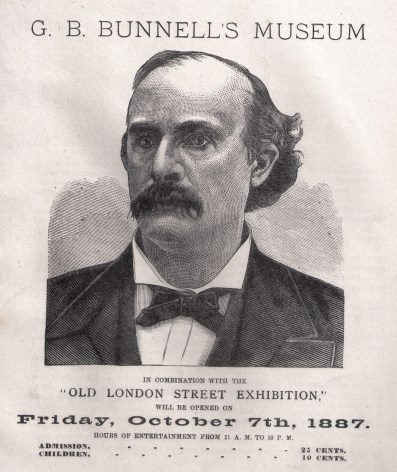

For a brief time, George Bunnell operated his museum at the Old London Street Exhibition, which occupied the old Church of the Messiah at 728-730 Broadway.

In fact, 18 years earlier, in 1877, a feline exhibition called the Cat Congress took place at George B. Bunnell’s New American Museum on the Bowery (not to be confused with P.T. Barnum’s old American Museum on Broadway, which burned down in 1865).

The impromptu Cat Congress also took place at Bunnell’s Museum in 1881 and 1882, when his dime museum was located on the northwest corner of Broadway and 9th Street.

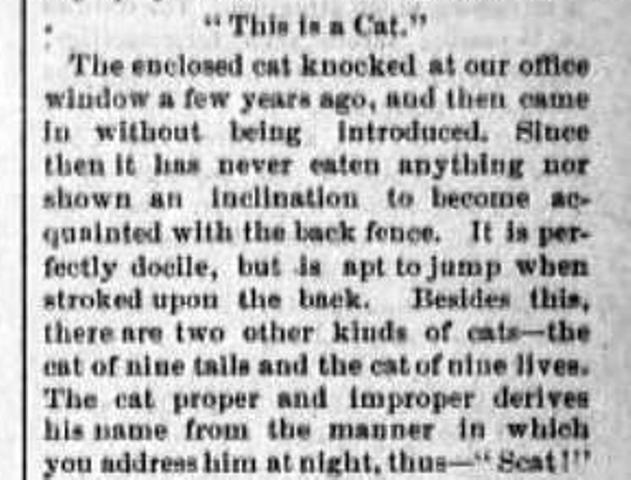

To kick off the 1881 Cat Congress, proprietor George B. Bunnell announced that he would offer a $10 prize for the best short essay on cats. The response was overwhelming: Within days, his office floor was covered with 557 funny, serious, and poetic essays about cats.

Here is a portion of Walter C. Quevedo’s clever winning cat essay, which he attached to a small wooden block called a “cat,” which was used in a child’s game called tipcap.

The briefest of the entries came from a man who said he hadn’t had a good night’s sleep in a long time: “Damn all cats anyway,” was all he wrote. The winning essay was written by New York World journalist Walter C. Quevedo of 127 Eleventh Street, Brooklyn, who attached his page-long essay to a little wooden “tipcat” game piece.

The Featured Felines of the Cat Congress

Some of the cats are remarkable for their size, color, stripes, and weight. By far the greater number possess all the characteristics of the back-fence tenors.–NYT, March 8, 1881

One of the felines featured at George Bunnell’s Cat Congress was a 13-year-old Tom cat named Humpty Dumpty. According to The New York Times, Humpty had previously been owned by the late George L. Fox, an American actor and comedian who had created a comical clown character called Humpty Dumpty in 1867.

The cat had reportedly won a life-saving medal for saving his owner’s life. As the story goes, Humpty Dumpty jumped up on George’s bed and started scratching his face to awake him one night after his house had caught fire. George had trained Humpty to do several tricks, and the senior cat was still able to perform a few of them in his old age.

Known as America’s first white-face clown, George Washington Lafayette Fox was famous for his clown character, Humpty Dumpty. Fox performed as Humpty Dumpty in over 1,200 shows over 10 years. He died at the age of 52 in 1877 — some reports state he lost his mind and suffered from paralysis as a result of lead poisoning from the white makeup he used every day on his face.

Another favorite at the show was a cat named General Washington. As reported, “General Washington was a black and white gentleman cat, with an intellectual breadth of forehead and a frank open face. His great-grandfather is alleged to have witnessed the surrender of Cornwallis some years ago. There may be some mistake about his ancestry, but it will not be denied that he himself is a handsome specimen.”

George Bunnell’s New American Museum

We first met dime museum proprietor George Bunnell in my post about a wolf that escaped on the Bowery in 1891. A protege of P. T. Barnum, George Boardman Bunnell played a large role in the development of the American dime museum after the circus man got out of the museum business. (It was Bunnell who first had the idea to reduce admission from a quarter to a dime.)

In 1876, George Bunnell purchased the collection of George Wood’s Museum and Metropolitan Theatre at 1221 Broadway, and opened his own New American Museum at 103-105 Bowery.

Three years later, he secured a lease for a brand-new four-story museum/music hall and lodging house at 298 Bowery. As with many theaters and museums of that era, Bunnell’s museum caught fire in June 1879, forcing him to find another location.

Despite a fire that destroyed Bunnell’s museum in 1879, No. 298 Bowery (white building, missing cornice), built in 1878, is still standing. The building was once identical to its neighbors to the right at Nos. 300 and 302, but time and use has taken a toll on the old building.

In 1880, George signed a 10-year lease at 771 Broadway, a four-story brick building owned by the Felix Effray estate. This building had previously been home to Effray’s French chocolate shop and L. Leroy’s drug store (1850s), and Wilson & Greig’s clothing and dry goods store (1860s-70s). It was here the Cat Congress of 1881 and 1882 took place.

Although the cat shows, dog shows, bird shows, and other events that took place at the New American Museum were quite successful, George Bunnell’s run at 771 Broadway didn’t last long. In 1883, the Sailor’s Snug Harbor Corporation, which owned much of the surrounding property, purchased the building from the Effray estate and cancelled Bunnell’s lease in order to replace the dime museum with shops.

For about two years, George B. Bunnell’s New American Museum occupied the four-story building at left. In October 1897, two men were killed in a fire at No. 773, to the right. Nos. 771 and 775 were heavily damaged by smoke and water.

Bunnell headed north and established a museum in Buffalo, New York. After this building was destroyed in a large deadly fire in March 1887, he took his museum to New Haven, Connecticut, which is where he stayed until his death on May 3, 1911.

The Randall House at 63 E. 9th Street

In 1955, a new 14-story apartment building called the Randall House was constructed on the northwest corner of Broadway and 9th Street, on the very spot where George Bunnell had his dime museum. This large apartment house fronts 9th Street, hence the address.

The Randall House is named for Captain Robert Richard Randall, a former sea captain who owned most of the land bounded by 9th Street, Waverly Place, 5th Avenue, and the Bowery Lane (4th Avenue)

Born in New Jersey in 1790, Robert Richard Randall inherited his father’s vast estate when the elder Tom Randall died in 1790. He used some of his inheritance to purchase the former Andrew Elliot 21-acre estate in the then-rural Greenwich Village for a sum of 5,000 pounds.

The “recent” history of this land goes back to 1766, which is when Andrew Elliot (acting colonial governor of the province of New York in 1780) purchased 13 acres extending from the Bowery westward to the present Sixth Avenue. Over the next few years he acquired eight more acres, on which he established an estate he called Minto, in honor of his father, Sir Gilbert Elliott, who was 2nd Baronet of Minto, a village in Scotland.

The Andrew Elliott estate is shown on this 1776 map created by Lt. Bernard Ratzer during the Revolutionary War. It’s to the west of what was then the Bowery (the main roadway running through the middle of the map), just north of the Sand Hill and south of the road leading east to the Peter Stuyvesant farm (present-day 10th Street).

After Andrew Elliott fled the city during the British evacuation in 1783, the property came into the possession of Frederick Charles Hans Bruno Poelnitz (commonly called Baron Poelnitz). The Baron in turn sold the property to Captain Richard Randall.

Captain Randall had no heirs, so at the suggestion of his attorney, Alexander Hamilton, who reportedly drew up Randall’s will, the old sea captain requested that his home be used as a “snug harbor” — a marine hospital for “the purpose of maintaining aged, decrepit, and worn-out sailors.” The land was good farm land, and Randall thought that the residents living at Snug Harbor would be able to grow grain and vegetables to help sustain themselves.

The Washington Mews homes and stables, on the southern edge of Randall’s 21-acre Greenwich Village estate, generated much income for the Sailors’ Snug Harbor trust fund.

Following Randall’s death in 1801, his will was immediately contested by relatives, and it was not until 1831 that the matter was settled by the Supreme Court of the United States. By this time, the property — which included the northern edge of Washington Square Park — had become so valuable that the Trustees of the Sailors’ Snug Harbor thought it better to subdivide the land into 253 lots and lease it out. The trustees used the money from the leases to purchase a 130-acre from on the north shore of Staten Island from Isaac Houseman for about $10,000.

The Sailors’ Snug Harbor opened on Staten Island on August 1, 1833, and continued to house aged sailors until the mid-1950s. Today, it’s part of the Snug Harbor Cultural Center and Botanical Garden. The Trust, considered to be one of the oldest secular philanthropies in the country, continues to assist mariners throughout the country.