Van Amburgh is the man, who goes to all the shows

He goes into the lion’s cage, and tells you all he knows;

He sticks his head in the lion’s mouth, and keeps it there a-while,

And when he pulls it out again, he greets you with a smile.–

“The Menagerie,” song by Dr. W.J. Wetmore, 1865

Part 1 of a 3-part story about Isaac Van Amburgh, the Richmond Hill estate in Greenwich Village, and New York’s Zoological Institute in the Bowery

After years of pressure from its many critics, SeaWorld finally announced that it was no longer breeding killer whales in captivity. The announcement followed on the heels of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus’ decision to retire all of its performing elephants by May 2016.

Although news reports suggest these announcements reflect a shift in society’s attitude toward the treatment of wild animals, one could argue that the criticism has existed for at least 200 years, going back to 1833, when a 22-year-old lion tamer from Fishkill, New York, introduced his wild animal act to New York City audiences in Greenwich Village and the Bowery. He was the Lion King of Old New York.

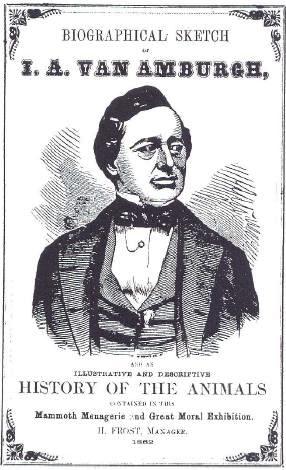

Much has been written about the lion tamer Isaac A. Van Amburgh, and I’d prefer to focus on the New York City ties to this story, but a quick introduction to the man who came to be known as the Lion King is warranted to paint the full picture.

In 1830, at the age of 19, Isaac Van Amburgh was hired as a cage cleaner for June, Titus, Angevine & Co., a large menagerie in North Salem, New York (later to become part of the New York Zoological Institute, founded in Somerstown Plains, New York in 1835 at the Elephant Hotel). Legend has it that Isaac was fascinated by the Biblical tale of Daniel in the lion’s den, and had always dreamed of being a lion tamer. He was a natural for the job.

That year, Isaac spent the warm months cleaning animal cages and the winter months training wild animals in various barns throughout upper Westchester and lower Putnam counties. By 1831, he was ready to take his traveling Van Amburgh Menagerie on the road. For the next forty years, Van Amburgh’s name would be synonymous with menageries, the circus, and daring wild animal acts.

The Lion King Takes His Act to Greenwich Village

In the fall of 1833, Isaac Van Amburgh announced his plans to step into a cage occupied by a lion, a tiger, a leopard, and a panther at the Richmond Hill Theatre, located at the southeast corner of Varick and Charlton streets in Greenwich Village. Strong appeals were made for him to cancel this performance, but he would not back down. He reportedly even offered to drive down Broadway and other main streets in a chariot drawn by lions and tigers, but the authorities interfered.

O.J. Ferguson wrote of the performance in Greenwich Village in his biographical sketch of Van Amburgh the Lion King published in 1862:

“The daring pioneer approached the door of the den with a firm step and unaverted eye. A murmur of alarm and horror involuntarily escaped the audience…The effect of his power was instantaneous. The Lion halted and stood transfixed. The Tiger crouched. The Panther with a suppressed growl of rage sprang back, while the Leopard receded gradually from its master. The spectators were overwhelmed with wonder…. Then came the most effective tableaux of all. Van Amburgh with his strong will bade them come to him while he reclined in the back of the cage – the proud King of animal creation.”

Dressed like a Roman gladiator in toga and sandals, Van Amburgh emphasized his domination of the animals by beating them into compliance with a crowbar. Oftentimes he’d thrust his arm into their mouths, daring them to attack. It’s no wonder that he had his share of critics, even in an era when four-legged creatures were called “dumb animals” and more often than not treated inhumanely.

When he came under attack for spreading cruelty and moral devastation, Van Amburgh responded to his critics by quoting the Bible: “Didn’t God say in Genesis 1:26 that men should have dominion over every animal on the earth?” To further make his case, Van Amburgh would act out scenes from the Bible, forcing a lion to lie down with a lamb or bringing a child from the audience to join them in the ring.

The Lion King performs. Does anyone else secretly wish these poor creatures would have attacked back?

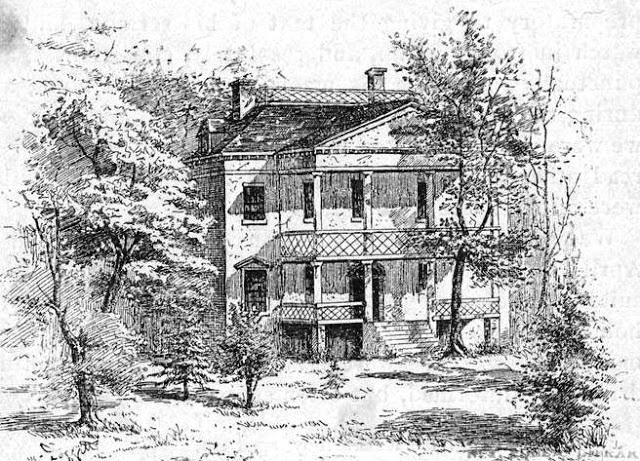

The Richmond Hill Theatre of Greenwich Village

I once took a walk along Charlton, Vandam, King, Macdougal, and Varick streets in Greenwich Village, to visit the former site of the old Richmond Hill Theatre, where the Lion King once performed. I first closed my eyes briefly and tried to imagine the scene 400 years ago, when the area was a favorite hunting ground for the Lenape, who came there to fish in the creeks and hunt deer, flying squirrels, and other wildlife.

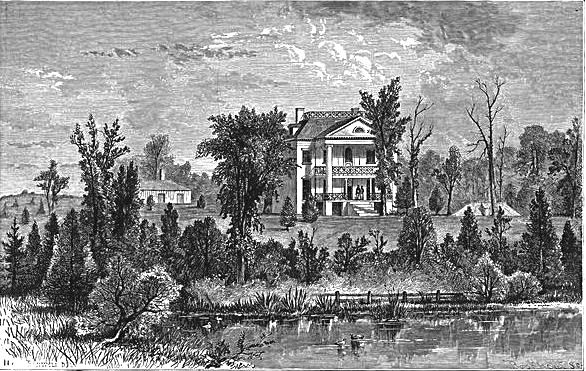

That proving a challenge, what with traffic police and taxis and buses and bicyclists, I next tried to go back 250 years, when the area comprised the 26-acre Richmond Hill estate, one of the finest and most famous in colonial New York.

The Richmond Hill mansion was built in 1767 by Abraham Mortier on grounds the British army’s paymaster general leased from the Trinity Church (99-year lease). The home of timber construction stood on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River, just west of today’s intersection of Charlton and Varick streets. (At that time, before the land was filled in, the property was very close to the Hudson River shore.)

In his book “A Tour Around New York and My Summer Acre” (1892), John Flavel Mines writes of the old Richmond Hill estate:

It was a beautiful spot then. In front there was nothing to obstruct the view of the Hudson. To the right fertile meadows stretched up towards the little hamlet of Greenwich Village, and on the left the view of the little city in the distance was half hidden by clumps of trees and rising hills. There was a broad entrance to the house, under a porch of imposing height, supported by high columns, with balconies fronting the rooms of the second story. The premises were entered by a spacious gateway, flanked by ornamental columns, at what is now the termination of Macdougal Street. Within the gate and to the north was a beautiful sheet of water, known to men who are still living and who skated on its frozen surface when they were urchins of tender years, as Burr’s Pond.

During her brief stay there, Abigail Adams wrote about Richmond Hill in a letter to a friend:

On one side we see a view of the city and of Long Island. The river [is] in front, [New] Jersey and the adjacent country on the other side. You turn a little from the road and enter a gate. A winding road with trees in clumps leads to the house, and all around the house it looks wild and rural as uncultivated nature. . . . You enter under a piazza into a hall and turning to the right hand ascend a staircase which lands you in another [hall] of equal dimensions of which I make a drawing room. It has a glass door which opens into a gallery the whole front of the house which is exceedingly pleasant. . . .There is upon the back of the house a garden of much greater extent than our [Massachusetts] garden, but it is wholly for a walk and flowers. It has a hawthorne hedge and rows of trees with a broad gravel walk.

Traveling back in my mind to the 1700s also proved difficult, as you can imagine, so as I tried to take photos in between bouts of traffic, I decided to ponder on the demise of Richmond Hill and the events that led to present-day Charlton and Varick streets.

Stay tuned for Part II of this Old New York lion tale, in which I’ll share what I’ve discovered about the final years of the old Richmond Hill mansion/theater where the Lion King once dominated a lion, tiger, leopard, and panther. And then in Part III, I’ll explore the old theater and Zoological Institute on the Bowery, where Van Amburgh developed his career as a formidable lion tamer and circus man.

Can’t help but wonder what was the power that Van Amburgh had over those poor animals. I’m awaiting to see his demise.

Can’t help but wonder what was the power that Van Amburgh had over those poor animals. I’m awaiting to see his demise.

[…] 1833: The Lion King of Greenwich Village and the Bowery, Part I […]

[…] 1833: The Lion King of Greenwich Village and the Bowery, Part I […]