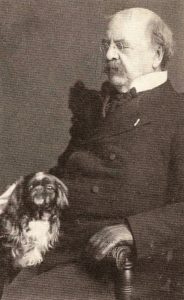

General Sickles with his Blenheim spaniel, Bo-Bo, sometime around 1904 in New York City.

“It is not surprising and will scarcely cause any comment if some soft-hearted or soft-brained woman goes into hysterics over the death of her pet dog or cat, and gives herself up to the most extravagant grief over his demise, but the spectacle of a veteran soldier who fought with distinction in the Civil War, doing the same thing, is rather strange.”—Arkansas Democrat, September 2, 1905

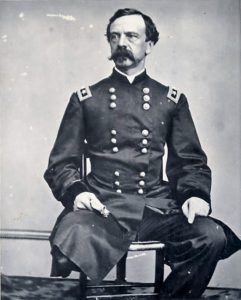

Born on October 20, 1819 (the birth year is not absolute), Daniel Edgar Sickles was the son of Susan Marsh Sickles and George Garrett Sickles, a New York City patent lawyer and politician. Much has been written about General Sickles, so for the purpose of this story, I’ll sum it up in one paragraph as follows:

General Daniel E. Sickles was a Tammany Hall politician; a murderer (in 1859 he shot and killed Philip Barton Key, the son of Francis Scott Key, but he was acquitted on the grounds of temporary insanity); a Civil War hero (he was awarded the medal of honor for his services at Gettysburg); a two-time Congressman; a good friend of the Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy (he purchased a lion cub for her in 1908 when she was living at the Plaza Hotel); and the owner of a purebred Blenheim spaniel named Bo-Bo.

Bo-Bo was a royal dog from the kennels of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, England. Born in 1902, he was reportedly purchased by one of Daniel Sickles’ relatives from Charles Richard John Spencer-Churchill, the 9th Duke of Marlborough. When this relative died a few months later, Bo-Bo was gifted to the general. The little dog spent the next three years living in luxury at General Sickles’ mansion at 23 Fifth Avenue, on the northeast corner of East Ninth Street.

During the Battle of Gettysburg, General Sickles was severely injured and had his right leg amputated. Although he had an artificial leg, he preferred to use crutches, with the empty pants leg pinned up slightly to show what he’d sacrificed for the country.

Although they had only a few years together, General Sickles and Bo-Bo were inseparable. They ate at the same table, slept in the same bed, and even went to work together.

According to reports, Bo-Bo would often accompany General Sickles to the Aldermanic Chamber at New York City Hall (Sickles was an alderman for the city’s Fifth District). There, he would lay quietly upon his master’s desk during the proceedings. Bo-Bo was quite popular among the aldermen, and even had a calling card that read “Master Bo-Bo Sickles, Assistant Alderman.”

The Passing of Bo-Bo

In August 1905, Bo-Bo was stricken with distemper and pneumonia. A few weeks later, he took a turn for the worse. General Sickles called in veterinary surgeon Dr. Thomas Sherwood, who remained in constant attendance. Two nurses from a New York hospital were also called to the house to administer oxygen and provide other services for the dying dog on a 24-hour basis.

Just before he died on August 22 at 4 a.m., Bo-Bo crawled from the pillow where he had lain to General Sickles, who was keeping a constant vigilance next the bed. Bo-Bo licked Sickles’ hand, put his head against the general’s hand, and passed away.

Following Bo-Bo’s death, General Sickles was inconsolable. For two days, he sat beside his companion, refusing to leave the dead dog’s side. During this time, he made plans to give Bo-Bo a burial fit for a king. He ordered a magnificent wood coffin lined with tufted satin, which he topped with a small American flag and numerous roses and cut flowers. For several days, Bo-Bo lay in state in the front parlor at 23 Fifth Avenue.

Bo-Bo’s burial was originally scheduled for August 24, but the general had to postpone it because it took him some time to find a cemetery to accept his dog. He first approached the trustees at the Beechwoods Cemetery in New Rochelle, New York, where his father had purchased a family crypt prior to his death in 1887. They turned him down. He looked into several other cemeteries, but no one wanted to accept the general’s beloved dog.

Then a friend told General Sickles about the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery in Westchester County, where numerous dogs, cats, and other pets were buried. He was reportedly just about to investigate this option when the trustees at the Beechwoods Cemetery reversed their decision and allowed him to bury Bo-Bo in the Sickles’ family crypt.

Bo-Bo is buried in the Sickles’ family crypt at Beechwoods Cemetery. A staircase leading to a large underground vault is located just under the granite slab. The crypt is located in a prominent section of the cemetery, and is near the grave of the first wife of Daniel Webster.

Bo-Bo’s burial at Beechwoods Cemetery outraged numerous plot owners, who felt the dog’s presence would tarnish the cemetery’s reputation and dishonor all of the prominent New Yorkers buried there. Henry M. Lester, president of the cemetery’s board of trustees, said he received numerous letters from plot owners who demanded that the trustees hold a meeting at once and have the body of the dog removed from the cemetery.

“I’m very sorry that the dog was buried in the cemetery, but I don’t see what can be now,” Lester told the New York Tribune. “There is apparently no section of our charter which forbids the burial of animals, and if we dig up the body on our own responsibility and throw it out, I am afraid General Sickles might have a suit against us.”

One plot holder was particularly upset, and that was George Sawyer, the stepbrother of General Sickles. Sawyer’s mother, Mrs. Mary Sheridan Sickles, was the second wife of George Sickles. At that time, Mary was buried in the crypt alongside her daughter Pera Abou Quinn (George and Mary’s two other children and a niece are also buried there).

Sawyer accused General Sickles of burying his dog there out of spite, and threatened to take the case before the District Attorney and a grand jury. “All this talk about General Sickles wishing to be buried beside his faithful dog is nonsense. He owns a plot in a cemetery in Brooklyn, where his first wife and daughter are buried, and in all probability, he will have his grave beside them.”

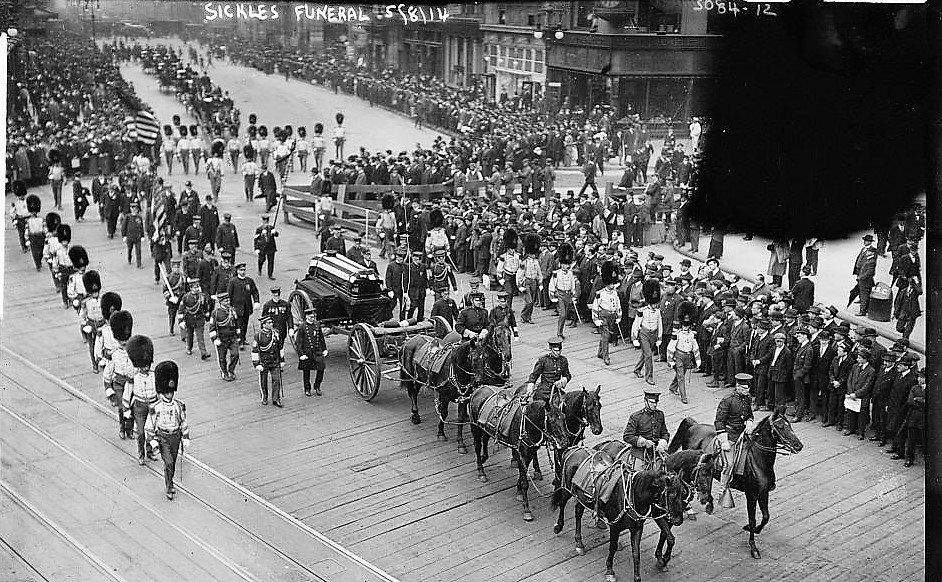

George Sawyer didn’t win the fight, and General Sickles wasn’t buried in Brooklyn. The general died in his home at the age of 91 on May 5, 1914. His funeral took place at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and he was buried at Arlington Cemetery.

On May 8, 1914, New York residents lined the streets along Fifth Avenue to St. Patrick’s Cathedral to mourn the passing of Daniel E. Sickles. The general is buried in Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery.

General Sickles’ Home at 23 Fifth Avenue

General Sickles moved into the four-story with basement townhouse at 23 Fifth Avenue after returning from Europe in 1879. At this time, the large house on the double-wide corner lot had been serving as the headquarters for the Northern Pacific Railroad Company (in the 1860s, it was a boarding house).

General Sickles lived in the corner house at 23 Fifth Avenue from 1879 until his death in 1914 (he also owned the adjoining house at 1 East Ninth Street). This photo was taken around 1920. New York Public Library Digital Collections

From 1905 to 1908, Mark Twain and his cat Bambino lived across the street from General Sickles at 21 Fifth Avenue, pictured here (far left) in 1935. All of these buildings, including the old Brevoort Hotel at right, were razed in 1952 to make way for the Brevoort, a large apartment complex that occupies the full block bounded by Fifth Avenue, East Eighth Street, University Place, and East Ninth Street. Museum of the City of New York

The home at 23 Fifth Avenue was constructed sometime around 1850 on a small section of what had once been the Brevoort farm, which comprised about 86 acres bounded by Ninth and Eighteenth Streets, Fifth Avenue, and the Bowery. A portion of the farm dates back to December 18, 1667, which is when Bastiaen Elyessen received the land from Richard Nicolls, the first English governor of New York.

The land passed from Elyessen to his son-in-law, John Hendricks Kyckuyt, on November 15, 1701. By that time, Kyckuyt had changed his surname to Brevoort (sometimes written as van Brevoort). Hence, the land became known as the Brevoort farm. Sickles’ house was on a portion of the land that had been deeded to Elias Brevoort, who was one of eight children born to Hendrick and Catherine Brevoort.

The Demise of 23 Fifth Avenue

When General Sickles’ father died in 1887, Sickles inherited about $5 million. However, by 1912 he had blown through the money and just narrowly escaped foreclosure on the house (his estranged wife of 27 years reportedly pawned her jewelry to prevent a sale at auction). The aging general was forced to rent out the top two floors. Bohemian art patron Mable Dodge Luhan rented the second floor (where she established one of the most famous salons in American history) and William “Plain Bill” Sulzer, an old Tammany politician, took the third floor.

Following his death in 1914, Sickles’ house and the neighboring house at 25 Fifth Avenue were sold in foreclosure proceedings brought by the Bowery Savings Bank. Sickles’ house was purchased by the bank for $104,850 and the adjoining dwelling went for $37,400.

Two years later, the Oak Point Corporation bought both properties with plans to construct a cooperative apartment building. The plans were put on hold due to World War I.

In 1919, the new Twenty-five Fifth Avenue Corporation purchased the two houses in addition to four neighboring townhouses. In 1921, the townhouses were demolished and replaced by a 13-story apartment house that still stands today.

The 13-story, full-service condominium building at 25 Fifth Avenue has about 90 apartments, a 24-hour concierge, gym, landscaped garden, and many other amenities. Cats and dogs are allowed.

Very interesting site and Facebook page…

A couple of corrections though:

Sickles was 94 when he died (October 20, 1819-May 3, 1914)

Francis Scott Key’s son was named Philip Barton Key.

Source: Wikipedia

Harriet, I am glad you enjoyed the story. You are absolutely correct when you do the math. The problem is, we really don’t know how old Sickles was at the time of his death because there are conflicting birth dates. According to the Civil War Trust, he was either born in October 1819 or October 1825. Here is what is reported on that site:

“Few figures of the American Civil War are more dubious than Daniel Edgar Sickles. His self-motivated actions on and off the battlefield have been debated by historians and buffs to this day. Even his date of birth elicits controversy. Daniel Sickles was supposedly born in New York City on October 20, 1819—although it is quite possible he was born on October 20, 1825.”

The article announcing Sickles’ death in the New York Times and other newspapers stated he was in his 91st year, so that’s what I went with that, even though it contradicts both birth dates. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=980CE6DB1438EF32A25757C0A9639C946596D6CF

And yes, that was a typo on my part regarding Philip Barton Key — good catch. I will fix that right now. Thanks!