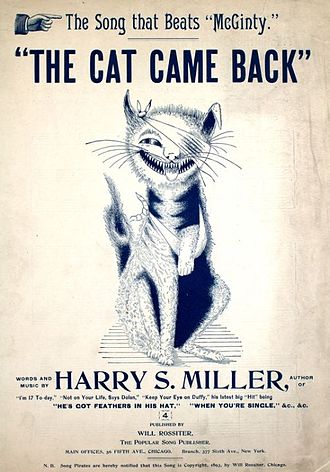

Sheet music cover for “The Cat Came Back,” written by Harry S. Miller in 1893.

In 1893, American lyricist and playwright Harry S. Miller–at one time a New Yorker–wrote a comic song titled “The Cat Came Back.” The original chorus to the whimsical ditty, which today is still a popular children’s song (or at least it was when I was a kid in the previous century), always comes to mind whenever I write about stubborn cats of Old New York that refused to leave their chosen home:

But the cat came back, he couldn’t stay no long-er,

Yes the cat came back de very next day, the cat came back—thought she were a goner,

but the cat came back for it wouldn’t stay away.

This song is especially appropriate for Minnie, the ship’s cat of the SS Fort St. George, which sailed out of Pier 95 on the Hudson River between New York and Bermuda in the 1920s.

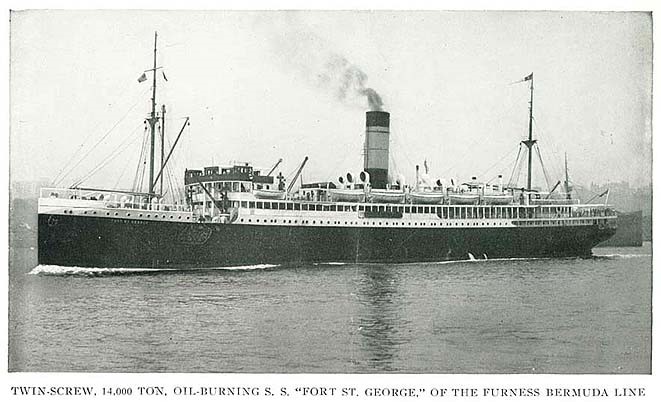

The Fort St. George of the Furness Bermuda Line

Originally built in 1912 for the Adelaide Steamship Company in Glasgow, Scotland as the SS Wandila, the steel, twin-screw steamship operated from Fremantle to Sydney, Australia until 1915, when she was acquired for military service and re-designated the HMAT Wandilla (His Majesty’s Australian Transport). Initially used as a troop transport for Australian soldiers, the vessel was converted to a hospital ship in 1916.

The Furness Bermuda Line’s Fort St. George was home to Minnie the cat for many years in the 1920s.

Following World War I, Wandilla was returned to the Adelaide Steamship Company and sold to Furness, Withy and Company, which had been awarded the mail contract for the New York to Bermuda run in 1919. The Furness Bermuda Line, which was under contract with the Bermuda Government, renamed the vessel the Fort St. George in 1921. Sometime around this time, Minnie chose this ship to be her home (I don’t know if she was born in New York or Bermuda).

The Fort St. George was modified by replacing her cargo holds with water tanks to supply fresh water to the hotels in Bermuda and also to accommodate 380 first-class and 50 second-class passengers in style.

The Fort St. George was known as a first-class vessel. All of the staterooms were fitted with electric lights, fans, and running water, and many rooms were equipped with beds as opposed to customary berths (in those days, passengers disembarked and stayed in Bermuda hotels.) A few private suites offered a sitting room, bedroom, and private bath. One of the big selling points were the full windows in the staterooms on the upper decks (as opposed to small portholes).

The Fort St. George and her sister ship the Fort Victoria (which sunk off the coast of New Jersey in 1929) sailed twice a week, leaving Pier 95 at the foot of 55th Street in New York City on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and returning from Bermuda on Tuesdays and Saturdays. The two ships were the only ones in the New York-Bermuda service that took passengers directly to the Hamilton Dock in Bermuda without a transfer tender.

Minnie, the Ship’s Cat

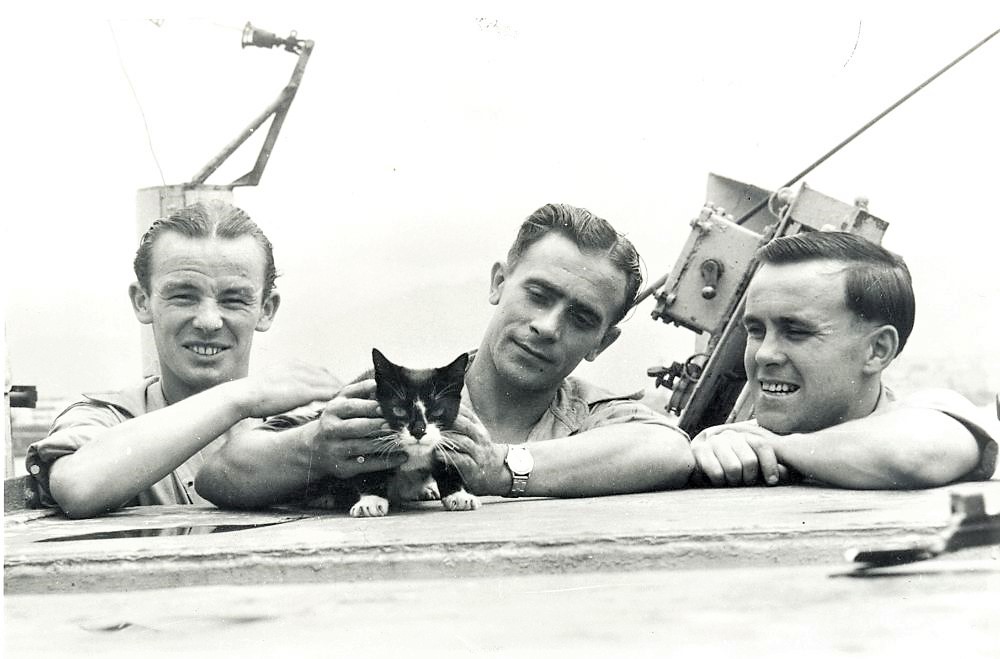

This is not Minnie, but I imagine this is what she may have looked like. This is actually Simon of the HMS Amethyst in 1949–also a great sea-cat story.

Minnie, the black-and-white cat of the Fort St. George, loved her home at sea, but she was also prone to flirting with the tom cats on Pier 95 in New York and at Hamilton Dock in Bermuda. In her years of service as the ship’s dedicated mouser, she was ejected from the ship at least 15 times. Not because she wasn’t loyal to her shipmates or good at catching rats, but because she gave birth to too many kittens.

Every time the sailors sent her packing with her kittens, she’d return as soon as her little ones were old enough to care for themselves.

One time a sailor reportedly took her all the way to Broadway and 72nd Street and bade her what he thought was a final farewell in front of the old Sherman Square Hotel. But when the ship entered Hamilton Harbor in Bermuda a few days later, Minnie miraculously appeared on deck. (My theory is that she hitched a ride to Bermuda on the sister ship, the Fort Victoria.)

They thought she were a goner, but the cat came back for it wouldn’t stay away…

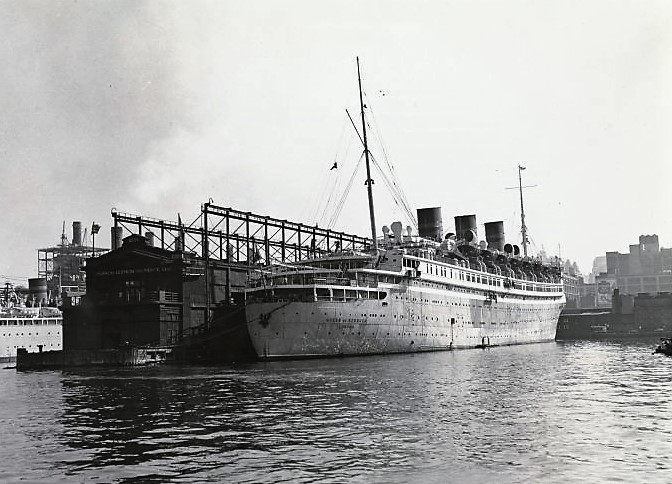

Pier 95 at 55nd Street

Pier 95 was a small city-owned dock constructed in 1916 at the foot of what was once part of the large estate of Cornelius Cosine. Only 60 feet wide and 700 feet long – considered a midget among the docks in later years — Pier 95 handled 100,000 passengers a year for the Furness Bermuda line.

The Furness Bermuda Line operated out of Pier 95 from 1920 to November 23, 1966, when the Queen of Bermuda, the last of the line’s ships, embarked for the final time. New York Public Library digital collections.

On August 31, 1925, a large fire damaged much of Pier 95. The fire began under the bulkhead at the far end of the pier, but it quickly spread. I’m not sure if Minnie was onboard at the time, but as the fire approached the Fort St. George, a pier watchman summoned some tug boats to quickly tow the vessel away.

The fire could be seen far up and down the river, and the smoke effected people as far east as Broadway. It took 350 firefighters, 35 pieces of apparatus, four fireboats, and several tug boats all day long to contain the blaze. Over a dozen firemen were overcome by smoke (a few were knocked into the river) and had to be treated at an emergency hospital station operated by Dr. Harry Archer, the Honorary Deputy Fire Chief. At midnight, flames were still making their way toward the shoreline and the appropriately named Burns Brothers coal dock.

Pier 95 was eventually repaired and continued to serve the Furness Bermuda ships until the line moved to Pier 88 at West 48th Street in 1966. The city then used Pier 95 for a municipal concrete plant and later as the city’s tow-away car pound.

Today it serves as a “get-down” pier as part of the Clinton Cove section of the Hudson River Park. It’s unique design allows people to get near the water in order to fish or just relax close to the river.

The Cornelius Cosine and Jacob Harsen Farms

Pier 95 was located at the foot of West 55th Street, which was once part of the vast holdings of the Cosine and Harsen families. (Where Minnie was dropped off 20 blocks north and several blocks east at Broadway and 72nd Street was also once part of the Cosine/Harsen estate, which shows you just how much real estate they owned.)

Born in New York sometime around 1718, Cornelius Cosine was the son of Jacobus Cosynszen and Aeltje Aumach Cosynszen. The Cosynszens (also referred to as the Anglicized name Cosine or Cozine) were early Dutch settlers who arrived in New Amsterdam around 1684.

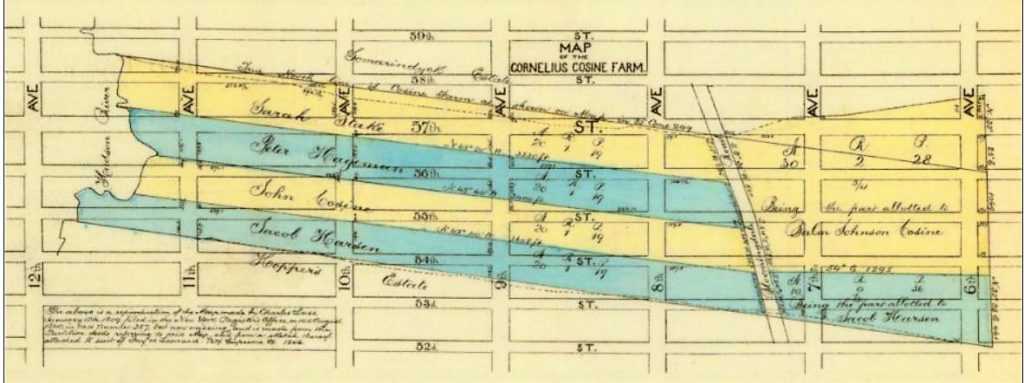

The 200-acre Cosine farm (1853 map) included lands under water at the foot of 53rd to 57th Streets.

Cornelius Cosine owned the family farm of about 120 or more acres between present-day 53rd and 57th Streets between the North River (Hudson) and the “common lands” near Sixth Avenue. (The family had reportedly received title to the land from James, the Duke of York.) Following Cornelius’ death in 1786, the land was deeded to his two sons, Cornelius Jr. and Balm Johnson.

In 1773, Catherine Cosine (1750-1835), the daughter of Balm Johnson Cosine, married Jacobus (Jacob) Harsen (1750-1835). The southern section of the Cosine farm was deeded to Jacob and Catherine in 1809. Over the course of the next eight years, the land went through a tangle of judgments, mortgages, and foreclosure sales, and eventually landed in the hands of John Jacob Astor for just $23,000.

Jacob Harsen was the eldest son of Johannas Harsen and Rachel Dyckman Harsen, who married in 1749. He was active in New York City’s political life, serving as both alderman and city magistrate, and he was also a ruling elder of the Reformed Dutch Church near present-day 68th Street and Ninth Avenue.

Both of Jacob’s parents were descendants of the Dyckmans, who were also early Dutch settlers. His father, Johannas, was the son of a farmer also named Jacob Harsen and his wife, Cornelia Dyckman. His mother, Rachel, was the daughter of Nicholas Dyckman (1692-1758) and Anneke Sevenhooven.

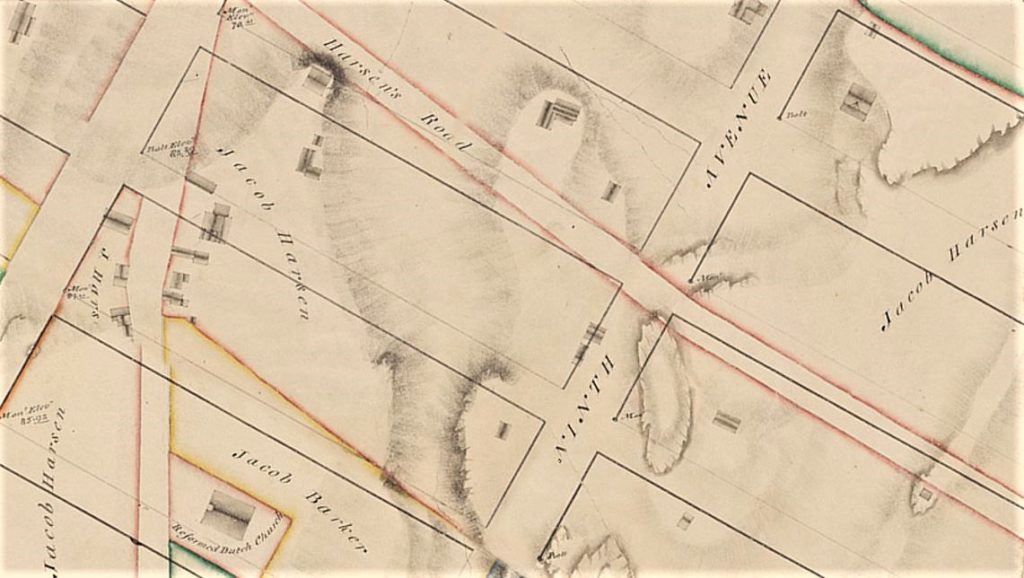

The Dyckman estate–later known as Harsenville–spanned 68th to 81st Streets between present-day Central Park and the Hudson River. Harsen’s Road (red) was a country lane that served as the main road for for the village and which ran parallel to present-day 71st Street. Jacob and Catherine’s homestead was located near today’s Tenth Avenue and 70th Street, as shown here on the Randel Farm Map, created between 1811 and 1820. Notice the nearby Reformed Dutch Church at bottom left.

Nicholas and Anneke Dyckman and their seven children lived on a 94-acre farm on the Upper West Side that had been in the family since 1701. The farm spanned 68th to 81st Streets between today’s Central Park West and the Hudson River. Following the death of her father, Rachel inherited the 94-acre Dyckman estate, which in turn passed to the younger Jacob and his wife, Catherine, sometime around the time of their marriage.

Jacob and Catherine moved into a homestead near present-day Tenth Avenue and 70th Street — only a few blocks from where the sailor took Minnie in the early 1920s.

The Village of Harsenville and Sherman Square

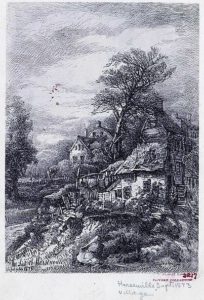

After Jacob and Catherine moved into their new home far away from nowhere, other tobacco farm families followed in their footsteps. Soon, a quaint village formed along Harsen’s Road, complete with schools, churches, and shops. At its peak in the mid-1800s, Harsenville had about 500 residents and 60 buildings.

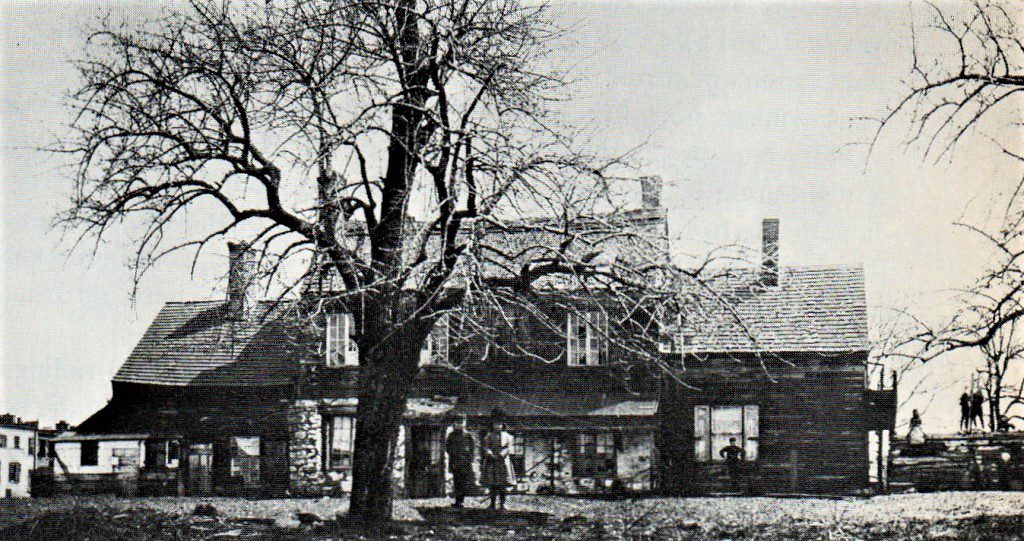

Jacob and Catherine Harsen lived in this homestead near Tenth Avenue and 70th Streets in the late 1700s and early 1800s. This photograph was taken 50 years after they had both passed, in 1888. We can clearly see two children by the tree, but also check out the silhouette of the woman in the window at right. New York Historical Society

Harsenville was still a bucolic village when this illustration was drawn in 1873, but development was just around the corner. NYPL Digital Collections

On March 31, 1849, as part of the widening of Bloomingdale Road (Broadway), the city acquired by condemnation a piece of Harsenville land wedged between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue between 70th and 71st Streets. The parcel was reduced in size in 1869 when 70th Street was opened from Eighth to Tenth Avenues, creating a small traffic triangle.

Following the death of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman in 1891, the Board of Aldermen voted to name the triangle Sherman Square, in honor of the man who had retired in New York and resided near the square.

It was from here that the abandoned but determined Minnie that cat set out to return to Pier 95 and her forever home, the Fort St. George.

By 1911, Harsenville was only a distant memory, its country lanes and farms replaced by brownstones and apartment houses in a part of Manhattan soon to be known collectively as the Upper West Side.

Development at Broadway between 71st and 74th Streets in Harsenville had just begun when this photo was taken in 1875. NYPL Digital Collections.

Here’s Sherman Square and the Sherman Square Hotel at Broadway and 72nd Street sometime around 1920, a few years before Minnie was left here to fend for herself (and fend for herself she did!). NYPL Digital Collections

I love this and thanks for writing it!

My grandparents sailed aboard the S.S. Fort St. George during their honeymoon in 1924. These new details about the ship and port are a gem.

Wow, I also used to love that song when I was a kid – I haven’t thought about it in years! Thanks for that moment of nostalgia, and also for another great animal tale – a feline working mom! I love it!

There’s a wonderful Canadian cartoon of “The Cat Came Back”.

[…] Road (today’s Broadway) between 70th and 71st Streets, before being reduced again in 1869 to create a traffic triangle. Soon thereafter, the Harsen family reportedly sold parts of their land in the 1870s and the end […]