Tommie Blackberry was a cat who owed his life as the mascot of the Jewell Day Nursery on MacDougal Street to the leader of the anti-suffragist movement in New York City.

“It seems almost a misnomer to speak of it as a ‘charity’ in the accepted meaning of the word. Far rather is it an expression of the true and highest signification the term can bear; the impulse which takes these little ones from their pitiful and often squalid surroundings, at the same time enabling their mothers to do their daily work with no care for the babies who too often, before the days of ‘nurseries’ were left locked in fireless rooms that the bread-winner might earn her pittance, is surely an outcome of love for one’s neighbor in its most beautiful shape.”–East Hampton Star, August 4, 1899

In May 1892, a law passed in New York City (the Act of May 17, 1892, Chapter 655) prohibiting all but immediate family members from making clothing and cigars in tenement apartments. As a result, many aunts, cousins, and nieces who were accustomed to working in the homes of relatives had to leave their children while they went outside of the household to find work to supplement their husband’s or family income.

Although New York City already had at least one day nursery at this time (for example, the Hope Day Nursery at 226 Thomson Street was established in 1888), the 1892 law helped feed a growing need for additional day nurseries throughout the city.

One woman in particular—Mrs. Arthur Murray Dodge (nee Josephine Jewell), a Vassar-college-educated activist and philanthropist—made it her mission to meet this need by sponsoring and founding several nurseries for children (and cats) in the 1890s.

The Jewell Day Nursery on MacDougal Street

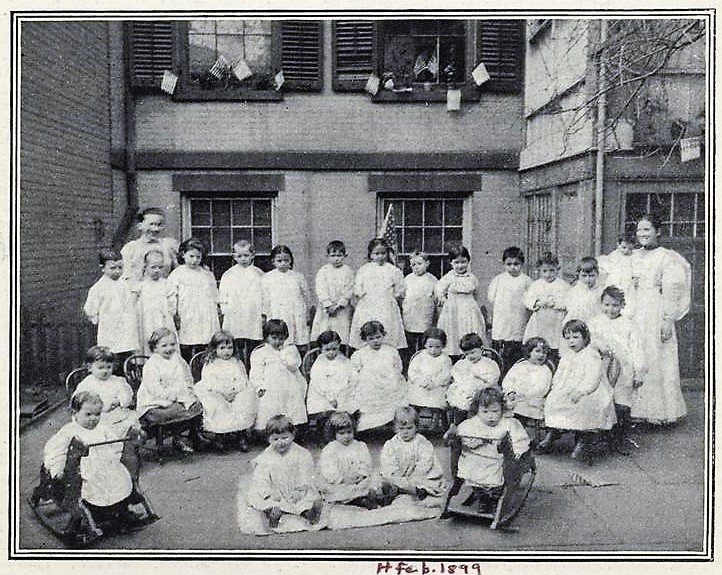

The children and matrons of the Jewell Day Nursery at 20 MacDougal Street in 1899. There was reportedly a large tree in the backyard, visible at right. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

A year after the Nursery Committee of the woman’s branch of the New York City Mission established a day nursery on the upper floor of 226 Thompson Street, the committee began looking for larger quarters to accommodate the demand. In May 1889, Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Murray Dodge purchased a large three-story and basement brick house at 20 MacDougal Street, and, after having thoroughly renovated it, presented it to the committee.

They requested the nursery be called the Jewell Day Nursery in honor of their four-year-old son Pliny Jewell, who had died only four months earlier. The mission of the day nursery was not simply day care, but also to educate immigrant children in “American” family values.

The new nursery opened on December 19, 1890, with 36 babies and toddlers (mostly the children of Italian immigrants) in attendance.

Arthur Murray Dodge died at the age of 44 in 1896 at the Dodge’s country home in Sinsbury, Connecticut, following a yearlong illness.

The Jewell Day Nursery was described as one of the finest in the city. In the basement was a kitchen with a large brick fireplace where chef Miss Bridget worked preparing the daily meals. The kitchen had an adjoining dining room that was furnished with long, low tables and little chairs.

On the first floor were two large playrooms filled with doll houses, rocking chairs, and other toys. Two rooms on the second floor were furnished with 20 cots for afternoon naps. There was also a reception room on the second floor. The servant’s rooms and matron’s apartments were on the third floor.

Outside, a backyard with a large tree had a space roofed over for playtime in the summer months. There was also a roof garden with a striped awning and bright flowers supplied by the Fruit and Flower Guild to help bring a little bit of country to the tenement children.

Working mothers drop off their children at the West Side Day Nursery and Industrial School in 1901. NYPL Digital Collections

The children would arrive at 7:00 a.m. and, if necessary, were bathed. They were then placed in clean gingham garments and allowed to play until lunch time at 11:00 a.m.

The afternoons were dedicated to kindergarten lessons for the older children or play for the toddlers. A second meal featuring fresh milk from a New York State farm was provided at 4:00 p.m.

Following dinner, the children were allowed to play again until their mothers–described in one newspaper as “an over-worked, under-paid boxmaker, or washerwoman or maker of ladies’ underwear—returned to take them home.

Sometimes, the children were treated to field trips to Coney Island or to the country farms in Montclair, New Jersey. The field trips provided opportunities for the children to get some fresh air and to see farm animals, fruit trees, flowers, and other things that did not exist in their part of the city.

The cost for all of this was 5 cents a day per child (which was fairly expensive for the working immigrant mothers, especially for those with several children). Numerous charity events such as an annual doll sale and musical performances were held throughout the year to raise additional funds for the nursery.

Tommie Blackberry Enrolls in the Nursery

The Jewell Day Nursery was more than just a refuge for children. It was also a temporary sanctuary for maimed animals, and in particular, stray cats.

Apparently, one day a small child brought in a starving kitten. Finding it kindly treated by Miss Miles, the matron, the child told his mother about the kind deed. From that point on, the nursery became a reception station for decrepit and anemic cats of the neighborhood until they could be passed on to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (where, sadly, they were probably placed in the gas chambers).

The Jewell Day Nursery at #20 MacDougal Street was in the three-story building to the right of the large six-story tenement buildings constructed in 1900 (extant) and the Eighth Police Precinct station house at #24-26 (the large building with the American flag, extant). Also pictured in the forefront of this 1926 photo are the home of the Second Assembly District Republican Club at #30 (with the awnings) and the former Richmond Hill settlement house next door at #28 MacDougal (both these buildings are extant). NYPL Digital Collections

One time a woman on nearby Varick Street gave a young boy a box filled with kittens and ice (it was a hot day, so she wanted to keep the kittens cool). She paid the boy 50 cents to bring the box to the nursery. One of the kittens so endeared himself to Miss Bridget, the nursery cook, that they decided to make him the nursery’s feline mascot rather than passing him on to the SPCA.

The children named the kitten Tommie Blackberry. I wish I knew how they came up with that name.

One day Tommie Blackberry went missing. Miss Bridget, “in dire distress,” walked down the street asking the neighbors and policemen if they had seen the nursery cat. For several days, numerous children brought stray cats to the nursery and asked Miss Bridget if it was Tommie.

Finally, four days after he went missing, a policeman returned the mascot, having found him “consorting with cobwebs beneath a porch up the street.”

Mrs. Arthur Murray Dodge and the Anti-Suffragist Movement

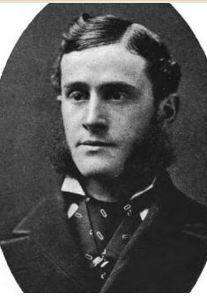

Mrs. Arthur Murray Dodge

“Never has there been a propaganda so destructive of great values as that which women now are preaching, marching, dancing, dressing. While suffrage must inevitably lead to the destruction of the old home idea, it offers for it not the slightest substitute. Even the word ’home’ is becoming a rare joke among the suffragists. From their platforms they continually ridicule us—the anti-suffragists—because we talk of it. That is a sad state of things, isn’t it?”—Mrs. A.M. Dodge, 1916

Born in 1855, Josephine Jewell Dodge came from a prominent family with strong political ties. Her father, Marshall Jewell, had been the governor of Connecticut, and was once considered for the Republican nominee for president. She was educated at Vassar, one of the few women’s colleges of the era (although she left college without a degree in 1873 to accompany her father to Russia, when he was serving as a diplomat there.)

On October 9, 1875, she married Arthur Murray Dodge, a graduate of Yale and a member of the lumber company Dodge, Meigs & Company. She and her husband had six sons: Marshall Jewell, Murray Witherbee, Arthur Douglas, Pliny Jewell, Geoffrey, and Percival. Three years after their marriage, she became the leading sponsor of the Virginia Day Nursery on Thompson Street.

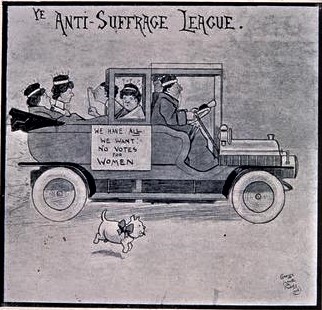

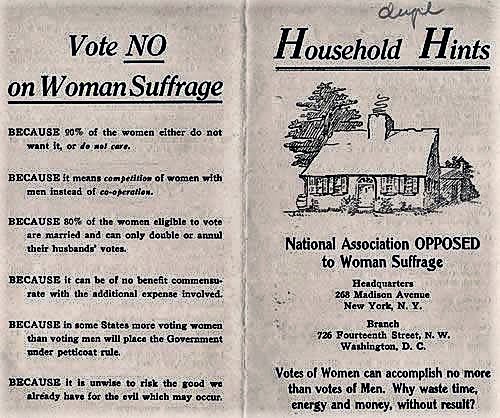

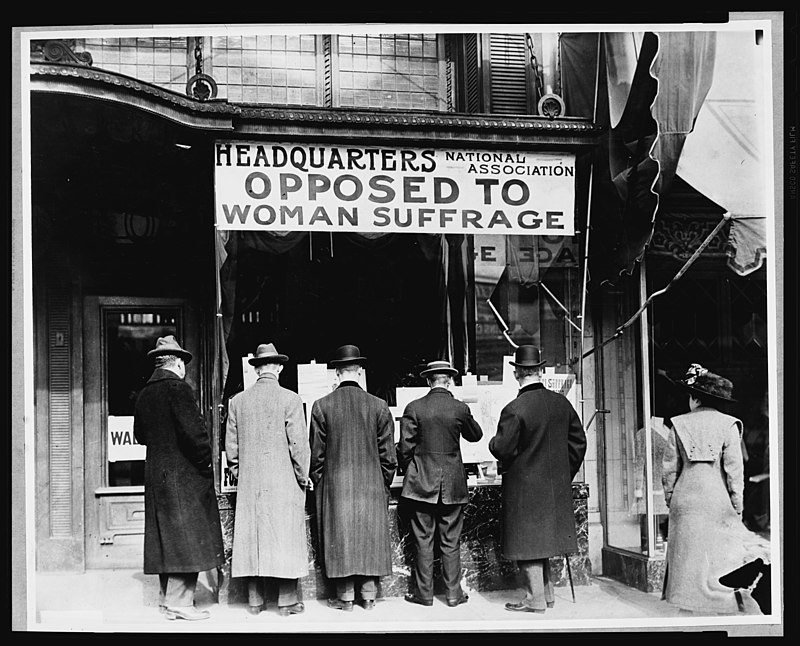

In addition to the day nursery movement, Mrs. Dodge was also very active with the anti-suffragist movement. From 1911 to 1916, she led the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS), which had its headquarters at 268 Madison Avenue in New York City. She also edited their newspaper, Woman’s Protest.

The anti-suffragists were against giving women the right to vote for several reasons. Maybe if women had been given the right to vote earlier, they wouldn’t have been making slave wages in the 1800s — or they could have voted for candidates who supported living wages for their husbands… Just saying…

Mrs. Dodge was against giving women the vote because she thought women would be better putting their efforts toward helping the greatest social problem, the child. More old-fashioned home training, she explained, was what was needed to prevent juvenile crime and other problems.

“It is not that women could not take up politics, but that there is no one left to do women’s work if she does,” she told the New York Times in 1915. “The extent to which suffrage agitation detracts from charitable enterprises and relief work is appalling, and the chief aim of the “antis” is to remove the political occasion of such a deplorable deflection of women’s duties from her field of highest efficiency and greatest service to the state.”

The national headquarters of NAOWS was at 268 Madison Avenue until it moved to Washington, DC in 1917. Looks like the men are more interested than the women…

Here are some other thoughts Mrs. A.M. Dodge shared with the press during this time (my eyes are rolling as I write this):

“No man ever made a home. It has been ever women’s work. If she refuses to accomplish it, then it must remain undone; if it remains undone, what can ensue but something close related to a social reign of terror?… I don’t want to seem discourteous toward my sisters in the suffrage movement. I believe the greater portion of them are not really aware of what they do. I am certain the majority of them do not desire to bring about destruction of the home, with all that must imply of loose or no domestic life; I believe many of them to be good mothers, and that among their younger workers may be many girls who are not infected and who will not become infected with a horror of the highest function given to woman by her God, that of motherhood… These things being true, is it not obvious that anything which takes woman from her home is dangerous? May I call attention to the fact that immigration of undesirable Europeans is coincident with our own decreasing birth-rate?”

Mrs. Dodge continued as president of the group until June,1917, when the organization shifted its headquarters to Washington, DC. She died in Cannes, France, in 1928 at the age of 72. I wonder whom she would have voted for in today’s world?

Following her death, the Jewell Day Nursery was combined with the Kip’s Bay Nursery. In October 1928, William D. Kilpatrick purchased 20 MacDougal Street from the Jewel Day Nursery.

20 MacDougal Street

Prior to its life as a day nursery, the three-story brick building at 20 MacDougal Street, constructed on the former Bayard Farm West, was home to James and Elizabeth Swan from about 1858 to 1883.

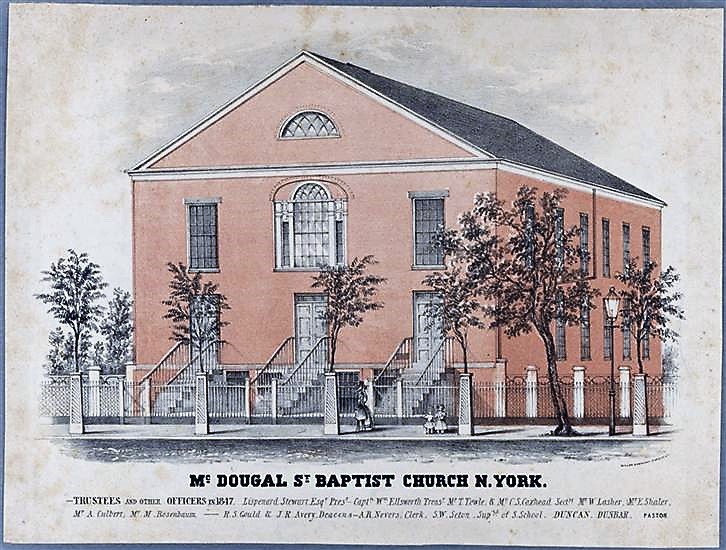

In early years, the home was adjacent to the North Beriah Baptist Church, which was organized in 1813 on lots 22-26 MacDougal Street at the intersection of “Van Dam” Street (previously called Budd Street until 1807).

In 1859, the church was renamed the Macdougal Street Baptist Church. The church merged with the North Baptist Church on West Eleventh Street in 1899 and in February 1900, Jackson & Stern bought the church and replaced it with three six-story brick tenement buildings that are still standing today.

The MacDougal Street Baptist Church was just north of the Jewell Day Nursery at 22 MacDougal Street until 1899, when it was torn down to make way for the tenement buildings still standing today at what is now 188-192 Avenue of the Americas. NYPL Digital Collections

Just north of the Baptist church were two similar three-story brick homes at 24 and 26 MacDougal Street. These were torn down and replaced by the new five-story brick station house and prison for the Eighth Police Precinct (later the Tenth Precinct) in 1893. This building is also still standing.

In 1918, Dr. Carlo Salvati purchased the house to the south of the Jewell Day Nursery at 18 MacDougal Street from Antonio Veniero. Sometime after 1928, he purchased 20 MacDougal Street and the two homes adjacent to the south, which were owned by Emido Repetto and Mary Mariscano.

In 1926, the buildings on the west side of MacDougal Street from Charlton to Vandam Streets were demolished to make way for the Sixth Avenue extension. On the east side, the brick building at 34 MacDougal Street, at the southeast corner of Prince Street (on the left of the photo above) was renumbered 204 Sixth Avenue. The former nursery at 20 MacDougal was renumbered 186 Sixth Avenue. The large, six-story tenement buildings were renumbered 188-192 MacDougal Street.

Fast-forward to 2007, when the four low-rise apartment buildings south of the large tenement buildings (180, 182, 184, and 186 MacDougal Street) were purchased by Gary Barnett, a real estate mogul and CEO of Extell. The purchase was made through the corporate name of SoHo Love, LLC.

Soon thereafter, demolition of the former nursery and its neighboring buildings to the south began (it was slow going due to asbestos concerns).

This Google Earth capture from 2007 shows the former Jewell Day Nursery building at 20 MacDougal (left) and its neighbor at #18 just before they were demolished to make room for an ultra-modern 14-story condominium tower. Just to the right and out of view was a Dunkin Donuts shop that was also torn down. One of the three six-story tenement buildings constructed in 1900 is at left.

For almost seven years after the former nursery and its neighbors were demolished, the lots sat empty while SoHo Love went through tons of red tape to get some love and approval for its proposed project, One Vandam. Built in 2013, the limestone and glass luxury condominium building features ultra-modern apartments and penthouses with prices starting at $1.54 million for a 737-square-foot one-bedroom and $15 million for a four-bedroom duplex with three terraces.

In this Google satellite view, One Vandam is on the right. The three, six-story tenements are to the left, followed by the former police station (dark brick) and the former Richmond Hill settlement house and Second District Assembly Republican Club headquarters building (both covered by foliage).

It was fascinating to see how many of the buildings from the earliest photograph are still standing. Thanks yet again for a great read!