How far would your cats be willing to go to catch a rat? Would they be willing to jump in a river like this barge office cat Old New York once did?

My two cats live indoors, and I’ve yet to see any type of rodent in my house, but I’d make a pretty high wager that neither Boo nor Misha would jump into a lake or river to catch a rat. In fact, I can easily picture them putting on the jelly-bean brakes at the edge of the water and watching the rodent swim away.

Richard II the Barge Office cat was an extraordinary exception to the feline rules. According to his owner, policeman Richard “Dick” Ganley, Richard II would do anything to catch a rat—he’d even jump into the Upper Bay and swim toward Governors Island or the Statue of Liberty in hot pursuit. Richard II could swim better than any duck, and it never took him long to catch up with the swimming rodents. According to Dick, his namesake always came out the winner, whether hunting rats by land or by sea.

A Brief History of the U.S. Barge Office

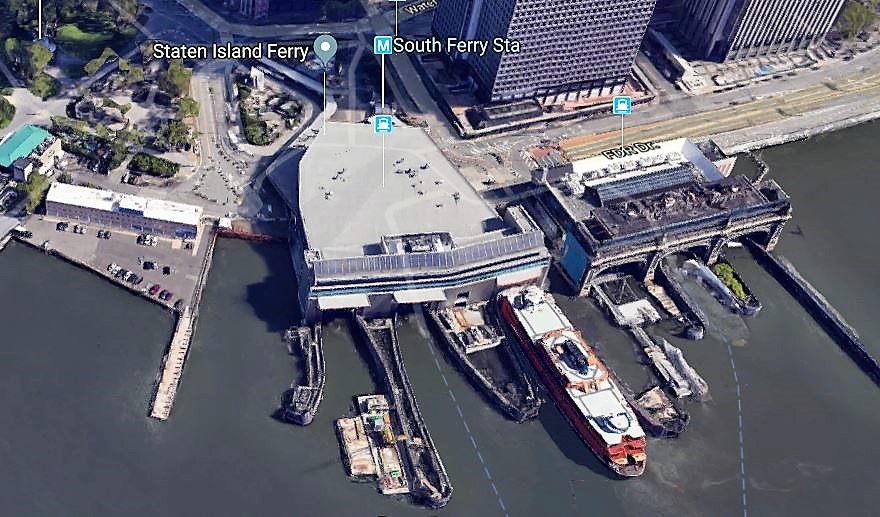

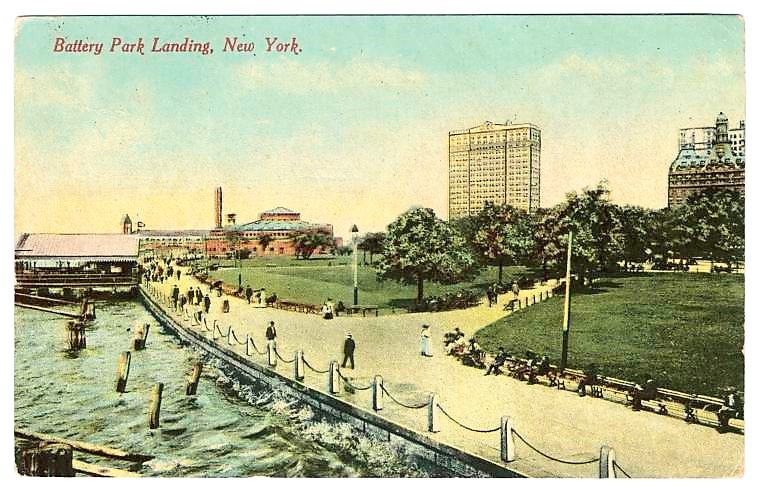

Dick Ganley was a veteran police officer detailed to the United States Barge Office located in Manhattan’s Battery Park near the foot of Whitehall Street. The Barge Office fell under the New York City Police Department’s First Precinct, which was then bounded by Battery Place, Bowling Green, Broadway, Fulton Street, Castle Garden, and the Battery.

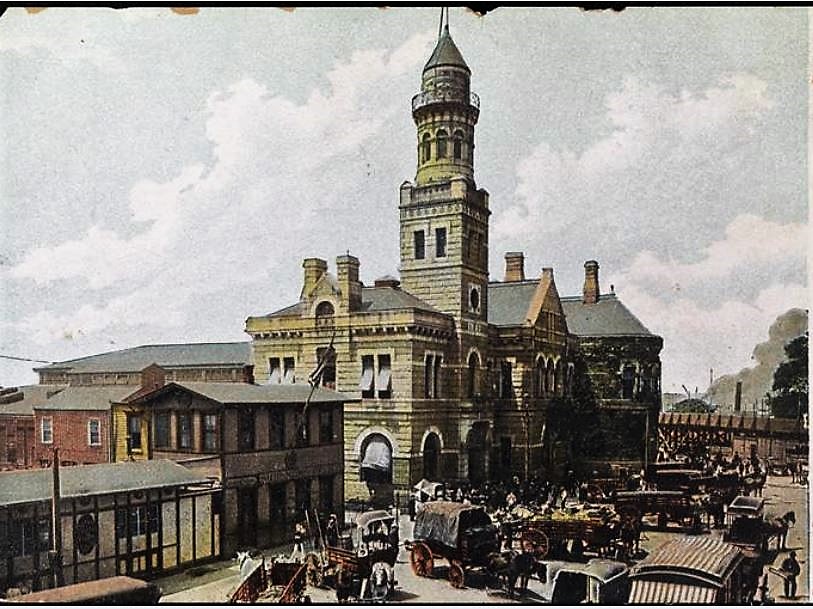

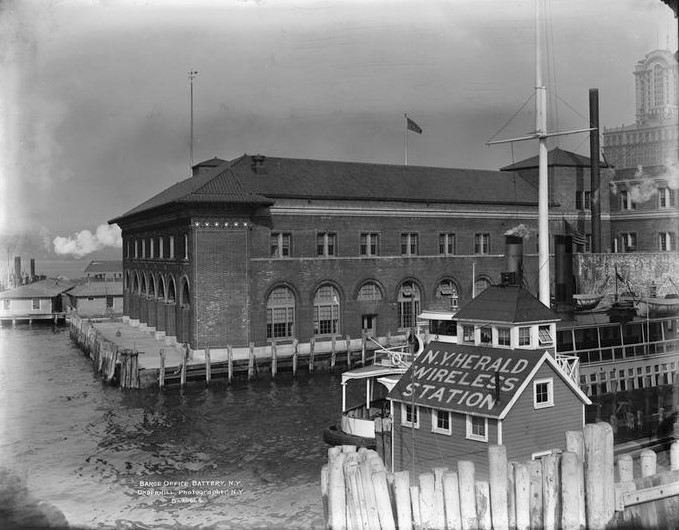

The original Barge Office was a frame building located on a strip of land formed by the junction of the East River and two water inlets — one running up Whitehall Street and one up Broad Street. After the War of 1812, the building was moved to the foot of Whitehall Street, as pictured here in 1860. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

In the early 1800s, transatlantic cabin passengers were literally treated like cattle, and were transported from their steamers to the Barge Office with their baggage on large barges–hence the name. In the late 1800s, a long, low iron structure was added to the stone Barge Office building to accommodate these passengers.

The Barge Office contained branch offices of the Custom Service, Coast Guard, and Immigration Service. It was also here that ship-news reporters gathered to meet incoming liners (notice the ship-news building in the 1860 photo above).

One of the primary functions of the Barge Office during the late 1800s and early 1900s was to assist immigrants who had just arrived at the Castle Garden receiving and processing center. Barge Office employees would help immigrants make arrangements for transportation and housing or locate friends and family in the city, and offer other assistance as needed to those either arriving in or leaving the country. Customs cutters also left from the Barge Office to meet those ships sent to Quarantine.

As one of the few policemen assigned to Battery Park in the early 1900s, Police Officer Ganley’s main job was to protect the newly arrived immigrants from the pickpockets and thugs who preyed on them. At this point in time, immigrants were required to have at least $50 in their possession; unscrupulous men called “runners” would threaten or even assault immigrants if they refused to pay them exorbitant rates to escort them to hotels or train stations.

Officer Ganley began working at the Barge Office in 1883, one year after the United State Congress federalized immigration control under the 1882 Immigration Act. Although the U.S. Treasury Department subcontracted New York’s Emigration Board to continue operating Castle Garden for several years, in 1890 a federal inquiry determined that the depot was inadequate and ordered its closure.

While the new facility was being constructed, the immigrant reception center was moved to the Barge Office. The small Barge Office received and processed all immigrants from 1890 until the U.S. Office of Immigration opened its brand-new Ellis Island facility in 1892.

Even after Ellis Island opened, some immigrants still came to the Battery after examination at Ellis Island. (A Department of Labor ferry was used to transport the immigrants.) Additionally, the iron structure located behind the main stone building was used as a storage place for immigrants’ baggage and as a temporary waiting room for ferry passengers.

The 1911 Barge Office building almost saw its final days in 1939, when Park Commissioner Robert Moses announced plans for a Battery-Brooklyn Bridge. The plan was for the Secretary of the Treasury to grant New York City an easement over the Barge Office site in exchange for a strip of land 105 feet wide to be taken from Battery Park for a new Barge Office site.

Plans for a suspension bridge between the Battery and Hamilton Avenue in Brooklyn were approved by the City Council in 1939 at an estimated cost of cost of $41.2 million. This plan was later scrapped for a Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, so the Barge Office was saved.

However, in 1942 Moses announced plans to revamp Battery Park by razing the Barge Office and the old Fort Clinton (Castle Garden), and replacing the sites with trees, shaded walking paths, and a promenade. Although the foundation of the old fort was preserved as Castle Clinton Monument, the Barge Office was demolished.

The Boss of Bedloe’s Island

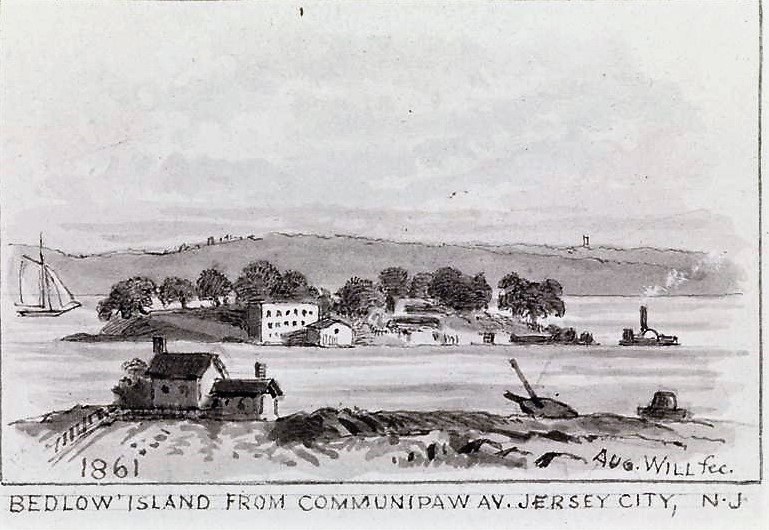

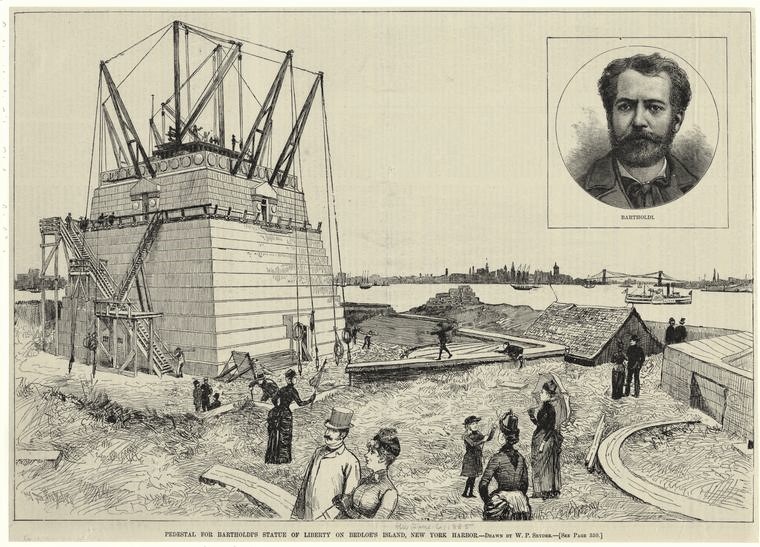

The year that Dick Ganley started working at the Barge Office is significant, because it was three years before the Statue of Liberty was placed atop her pedestal on a small island in Upper New York Bay called Bedloe’s Island, now known as Liberty Island. Dick was one of the very few civilians to have a front-row seat to the erection of the Statue of Liberty.

According to articles published in the New York Times in 1886 and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1938, Dick had been living with his family in a little government-owned house on the island before Lady Liberty arrived (the Ganley family and a watchman and his wife—Mr. and Mrs. Swords–were reportedly the island’s only inhabitants at this time). Dick, who raised roosters and engaged them in cock fights on the island, was known as the Boss of Bedloe’s Island.

Every day Dick would row a small boat to and from the Barge Office. The boat belonged to Battery boatman Bill Quigley, a Brooklyn resident who used his small rowboat to meet ships and haul in their lines to the pier.

Barge Office Dog Man Turns Cat Man

Dick Ganley was not really a cat man. In fact, the well-known “sporting cop” was quite active with the American Kennel Club. In addition to raising roosters, Dick had a large Newfoundland dog named Jumbo (not this Newfoundland named Jumbo), and he also bred stud dogs at his kennels when he lived in Brooklyn. Dick also kept a hunting rifle on the island, which his wife once used to shoot at some seals in the river (she reportedly missed all three shots).

Perhaps his sporting ways is why Dick did not hesitate to clip his cat’s ears and tail (Dick said he did this in order to be able to identity Richard II “beyond the shadow of a doubt” should the feline stray or be stolen). But I’m sure you agree with me that clipping the ears and tail was a very cruel thing to do.

Dick found Richard II under a bench in Battery Park in 1901. The tiny kitten, which Dick called “the finest, smartest, and the ugliest cat in creation,” had already lost eight of his lives by the time Dick came to his rescue.

As one article in the New York Times noted, “no cat or any other animal was so near death from starvation as this one when he discovered him and took him in charge.” After just a few days of food and loving care, Richard II quickly recovered and became “greatly attached to his preserver.”

The police officer was very proud of his cat, and he believed that the cat was just as proud of him. Every time Richard II caught a mouse—which was quite often—he would bring it straight to Dick to show that he was doing his job while on duty. In addition to jumping into the water after rats, Richard II would also hunt inside the steamships and other vessels tied up at the piers.

“Sometimes when there’s nothin’ doing at the office or in the park, he’ll take an hour or so off and go for a stroll up the river,” Dick told the Times reporter. “You can gamble that he’ll bring back one or two big ones and you’ll never lose.”

In April 1901, when the Times reporter interviewed him, Dick said he was going to exhibit Richard II at the next cat show, adding that if he didn’t win a ribbon he would “take the matter to law.” Dick added, “I wouldn’t swap him for any Maltese or angora in existence, and Pierpont Morgan hasn’t got enough money to buy him.”

Tozer, the Barge Office Dog

The same year that Dick Ganley rescued Richard II, he also rescued a half-breed fox terrier whom someone named Tozer. When Dick found the dog in 1901, he was so hungry that he could barely stand. The police officer hurried to a nearby delicatessen and purchased a banquet for the dog. Then he brought Tozer into the Barge Office building and placed him on a horse blanket no longer in use.

For the next five years, Tozer lived along the docks on South Street by night and in front of the Barge Office by day. According to one news article (the story was covered in a few dozen newspapers across the country), “Every policeman, every tramp, every longshoreman, every newsboy, and for that matter everybody who had business that took him to South ferry and South Street more than once a week knew Tozer, for Tozer was the smartest, sleekest little tramp of a dog that ever begged a meal from a free lunch counter.”

Tozer disappeared from the Battery Park area in September 1906. Some of his friends thought he may have found passage on a Nova Scotian schooner to the West Indies and would eventually show up again. No one believed he had been killed (unless by accident).

A New Barge Office Cat: Richard III, the Vegetarian Cat

In June 1901, Dick acquired another cat from a sailor from Cuba (or as Dick pronounced it, Cuber). Dick named the cat Richard III. According to Dick, Richard III was a mean cat who could “give ‘em all the cards in the pack an’ still beat ‘em out.”

Dick said he came upon this new cat after telling the sailor about his swimming cat. As was reported in the Dietetic and Hygienic Gazette, the Cuban sailor told Dick, “Your cat may be all you say, but if it’s a mean, fightin’ reglar champion-of-the-world anermal that you’er lookin’ for, I kin trot out a anermal from Cuber that kin whip any cat that was ever born.”

Dick replied, “Now, don’t git gay. If you’ve got a cat thet kin whip mine, I won’t do a thing but git off the force and spend ther rest of me life takin’ in ther sights o’ Brooklyn.”

The sailor led Dick up the gangplank and into his ship, where Dick came upon “a cat the likes of which no man on this earth, onless he seen thet perticklar one, ever seen. White and black, with spots of gray here an’ there, with eyes a color thet made him seem to all appearances a albiner, the cat made er sight fit to scare all ther cats in New York ter deth. He has ther shape of er tiger, ther eye of a lion, an’ ther spots of ther leopard.”

When the sailor offered the cat to Dick, the police officer jumped at the deal. He soon discovered that Richard III did not like meat. In fact, Dick said he was a vegetarian cat that only ate cabbage leaves, watercress, turnips, and carrots.

Dick said he planned on entering both cats in the cat show and that he expected two prizes: “One’ll be for the ugliest cat, that’s Richard II, an’ one fur ther meanest cat, that’s Richard III.”

The Ugly Side of Immigration at the Barge Office

Before my God, I might not this believe,

Without the sensible and true avouch

Of mine own eyes.

By what right or law is there in this city a typical bully…with a rawhide whip (I mean a rawhide whip three feet long) teaching the immigrants at Battery Landing the language of this land, thus:

One lash—Get back!

Two lashes—Get back quick!

Three lashes—Get back and run!—

Pegram Dargan, Letter to the Editor, New York Times, March 26, 1902

Policeman Ganley may have been kind to animals (excluding the incident with clipping his cat’s ears and tail), but I’m saddened to think that he may have been cruel to the human immigrants. In 1902, much attention was directed to the police methods at the Barge Office landing. The news articles do not name specific officers, but I think it’s important to share the content of these stories, especially in light of recent events in our world.

On March 26, 1902, a poet named Pegram Dargan wrote a letter to the editor describing a beating he had witnessed at the Barge Office. His letter would be viewed as greatly offensive today; I’ll share part of it here:

These people are pitiably innocent and manageable; yet this ruffian, glaring like a bull, falls upon them as sheep or dogs, and beats them at his own will and pleasure. If they are so many cattle, keep them out; if citizens, disgrace them not at their very entrance upon their citizenship…I yesterday saw a man slashed three times, though hurrying out of the way as fast as he could. This is a rather peppery sauce, at least, to the dish they have traveled some thousand miles to taste… I have no objection to these ‘know-nothings’ being pushed and cuffed, which they are from the time they touch the wharf till they vanish; let them be clubbed, this is no matter; but a lashing with a whip is no more in these states ‘American.’

(Apparently clubbing innocent people was considered “American” back then?)

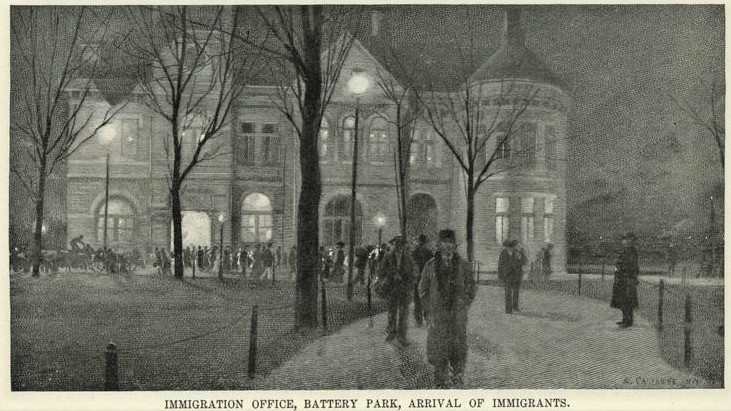

In response to this letter, the New York Times published a lengthy article about the Barge Office, which at this time was being used as a landing place for “such foreigners as are adjudged competent to enter the country as prospective citizens.”

According to the article, on busy days there were from 500 to 1,000 immigrants processed at the Barge Office, and about four to seven police officers (a few in uniform and a few in plain clothes) on duty to protect them. It was the police officers’ duty to prevent fights, keep the roadway clear for traffic, and force back the pickpockets and runners preying on the immigrants.

Here’s what a typical scene looked like, as reported by the newspaper:

After stepping upon the landing from the immigration tug, the immigrants file out toward the gate, herded together like droves of cattle. They are tired from their travel. There are men, women, and children: Italians, Orientals, Scandinavians, Englishmen, Irishmen. From the boat to the gate they are urged forward by immigration employees, who do not stand on ceremony, but shout ferociously and wave their small sticks, sometimes striking men or women who move too slowly… When the immigrants are few, they are not treated so very badly, although the shouts at them are always harsh. When they are numerous, the sticks of the officers and bureau employees are plied freely…

The writer of this has seen the police officers—not very often, to be sure—strike women until the latter sunk sobbing on the sidewalk… The sticks are not heavy, and it is more than probable that those who weep over their blows are more grieved by the indignity (though they are but immigrants) than over the physical pain. The argument of those who do the beating is that they cannot keep the crowd in order in any other way. It was suggested to one of them the other day that more policemen and employees might be placed on duty at the landing. ‘What’s the use?’ he responded. ‘You can’t manage these folks unless you treat them like dogs. They’re used to it on the other side.”

I’ll leave it at that for now.

In my next post about a dog that saved a man’s life during the great fire at Ellis Island, I’ll write some more about the history of Castle Garden and immigration in New York City.