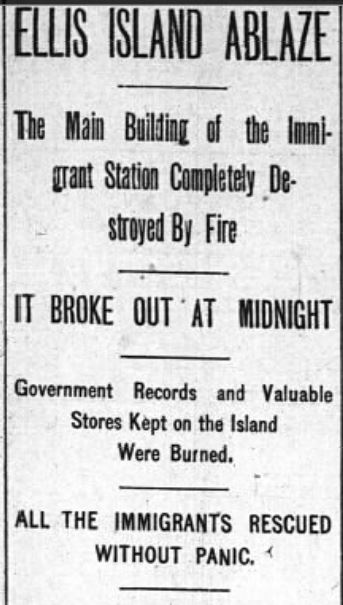

On the morning of June 15, 1897, a large fire destroyed the immigrant landing station that covered most of Ellis Island, causing a property loss of close to $1 million for the United States Government.

Every immigrant escaped unharmed, thanks to the watchmen, attendants, doctors, and nurses who came to their rescue. All of the employees were also accounted for, thanks to the heroic pet dog of Dr. Joseph H. Senner, the Commissioner of Immigration.

Dr. Joseph H. Senner was appointed Commissioner of Immigration in March 1893. Born in Moravia, Austria, in about 1847, Dr. Senner came to America in 1880 to work as the foreign editor of the New York Staats-Zeitung. The publication recommended Dr. Senner for the federal position.

At the time of the fire, there were about 180 to 250 immigrants at the station (news articles report different numbers). These people had arrived the day before on three ships: the Spaarndam from Rotterdam, the Alsatia from Genoa and Naples, and the Furnessia from Glasgow.

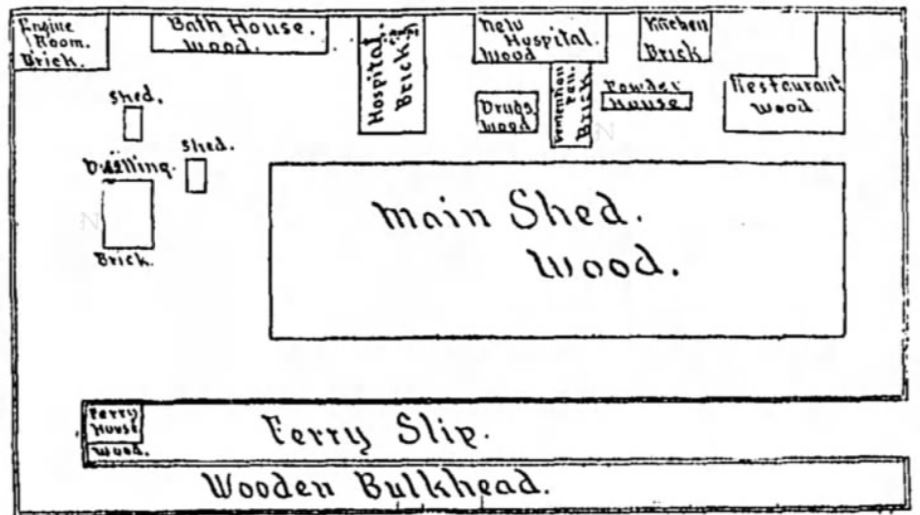

Most of the detained immigrants were sleeping on benches and wire cots in the large, L-shaped main building when the fire broke out (the single women were on the third floor, the single men were on the lower floor, and families were in the L wing). Another 40 people were in a hospital building near the rear of the main structure.

The fire was discovered at about 12:20 a.m. by night watchman William Gaines, who was making his rounds when he first noticed a reflection of flames in the window. News reports greatly differ on the origin of the fire: one report said Gaines discovered the fire in the office of Charles Ichlar, the chief clerk, which was on the second floor of the northeast tower. Another newspaper said it was Captain William J. Burke, superintendent of the watchmen, who had discovered flames in the northwest tower.

The New York Times reports that the fire originated in the restaurant and cookhouse just behind the main building. The New York Sun also noted that the first flames were observed on the western end of the building, near the restaurant.

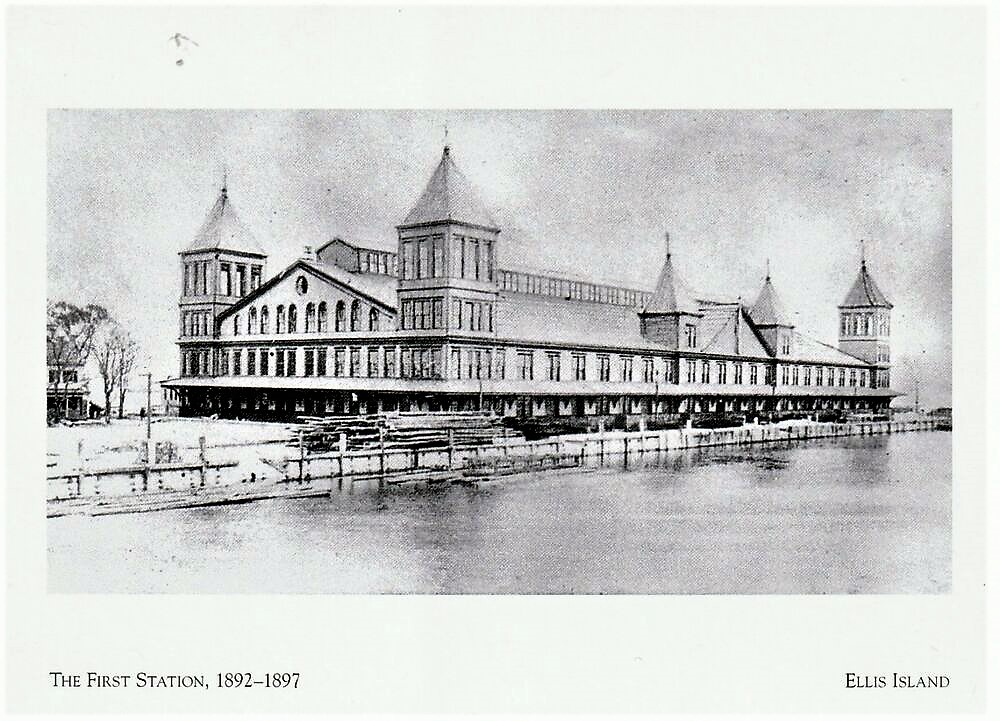

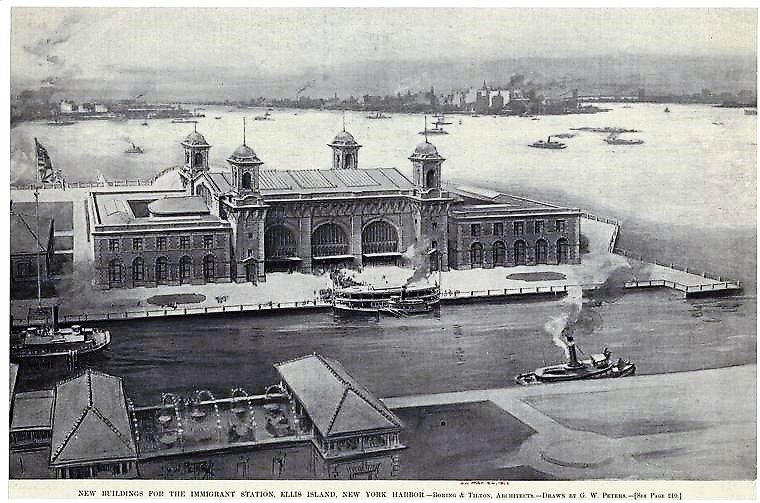

An illustration of the first Ellis Island Immigration Station in 1892. Reportedly, more than 4 million feet of lumber was used in its construction.

In any case, when the alarm for fire was sounded, Captain Burke immediately summoned the 15 men employed under him, including Joseph Kelly, Samuel (or William) Christensen, and Edward Goetty, who in turn unlocked the iron gates leading to the three-story “detention pen.” The gate man, engineer, four island-based firemen, several island-based policemen, and numerous hospital employees also assisted in rescuing the immigrants.

Hearing the cries warning of fire, many of the immigrants became hysterical or froze in fear and had to be carried out by the watchmen, doctors, nurses, and attendants. Many of the heroic rescuers were women: Mrs. Sophie Ruff, the matron, lined up all the women and children in the family ward and marched them to the ferry boat. Miss A. Holtz, a nurse, carried out four children from the hospital.

Once outside the burning building, some of the people tried to run back in to save their baggage (about 900 of the 1,400 pieces of luggage had been saved because it was stored at the Barge Office). Captain Burke and his men worked hard to keep the people out while deckhands lined up along the gangway to prevent the frightened immigrants from jumping into the river as they made their way to ferry boats, tugs, and barges that took them to the Barge Office at Battery Landing.

Everyone made it off the island save for about 15 people who were later found safe and sound on the north end of the island, where there was open space.

Jack the Newfoundland to the Rescue

While all this chaos was going on, one attendant who was not on duty that night slept right through the alarm and continued sleeping in an upstairs room. According to Samuel Peterson, he was sleeping in a room over the restaurant when he was awakened by Dr. Senner’s Newfoundland dog, Jack, who was trying to drag him out of bed.

Jack had reportedly run up the stairs and through the flames and smoke to wake Samuel, who had become overcome by the smoke. The dog also came to the rescue of one of the firemen who worked in the restaurant and slept in a room above Samuel’s room (again, news reports differ on the number of men who were rescued from the rooms above the restaurant).

Ellis Island Was a Fire Waiting to Happen

In 1892, shortly after the Ellis Island facility was completed, the New York World reported that the immigration station could never be salvaged in the event of a fire. Within a half an hour, according to the officials who were interviewed, any fire would destroy the brand-new Ellis Island buildings.

The large main building at Ellis Island had been constructed of Georgia and Florida yellow pine and northern white pine, all of which were very flammable. Although the building was sheathed in galvanized iron, experts predicted that this material could never act as a barrier to the intense heat that would be created in a fire.

Despite the upper-floor dormitories, there were no fire escapes, and no attempt was ever made to make the building fireproof. Also consider, the building was constructed on the site of an old ammunition storage facility used to store power and shells during the Civil War.

On the night of the fire, Chief Engineer James F. Bacon and Engineer Kelly, who were in charge of the engine house on the island, worked hard keeping two streams of water pouring onto the hospital building. Police officers from Pier A also assisted, and the fire boats New Yorker and Zephyr were put into operation, but every effort was to no avail.

As the New York World had predicted five years earlier, the buildings went up in flames “like a pile of old oil barrels.”

By the time the flames were under control, the main station, hospital, laundry, restaurant, doctors’ houses, and many other smaller outbuildings – a total of about 11 acres of property – were in ashes. In addition to the large monetary loss, all records dating back to 1840 were destroyed in the flames.

As The New York World reported the day after the fire:

“The United States Government did all it could to provide for a great fire. It constructed great piles of resin-soaked lumber, admirably arranged for burning, and they went up in flame and smoke almost as powder flashes in a pan. There is no regret for the Ellis Island buildings. They were a blot on the earth.

From the beginning they have been a scandal and a crying shame… If a private individual or corporation had put up huge buildings of inflammable pine on a little island in the bay which consists of about six acres, and had kept there as many as 3,500 persons from all over the earth, public opinion would have risen to its might. But the United States Government dared to do this thing.

Ever since the buildings were proposed the cry has been that they should be fireproof. As a matter of fact, they were simply material for a huge bonfire that risked more than two hundred lives.”

“The fire was the best thing that could have happened,” Dr. Senner told the press. “Not a single life was lost, nor was anybody injured in the slightest degree. So I am not grieving. A row of unsightly, ramshackle tinder boxes has been removed, and when the Government rebuilds it will have to put up decent, fireproof structures. I have been expecting something like this ever since I have been in office, but I never hoped it would be so little of a tragedy.”

Construction on a new, fireproof immigration station began in August 1898. The Ellis Island immigration center reopened on December 17, 1900; 2,251 immigrants were processed that day.

Two new islands created with landfill were added to Ellis Island in the early 1900s to house the hospital administration and contagious diseases ward and the psychiatric ward. By 1906 Ellis Island had grown to more than 27 acres — nine times its original size when Samuel Ellis purchased it in the 1770s. All 33 structures were closed in November 1954. The island was opened to the public in 1976 and continues to operate as the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration.

Castle Garden: New York’s First Immigration Station

While some people believe that all of our ancestors immigrated to the United States by way of New York’s Ellis Island, the island is only one part of the immigration story.

Prior to 1890, when immigration was still regulated by the individual states rather than by the Federal Government, millions of people arrived at other coastal and land borders.

Rules were fairly lax in early years: Immigration was at will, requiring newcomers only to report to customs and pay a fee. Under the Naturalization Act of 1790, all white males living America for two years were allowed to become citizens (you might call that white male privilege).

In 1847, as thousands of Irish and German citizens were coming to America via seafaring caravans in search of a better life or asylum (in the words of Thomas Paine, America was “the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe”), New York State lawmakers established the first immigration agency in the country. The agency was called the State Board of the Commissioners of Emigration (emigrant and immigrant being interchangeable back then).

Around this time, many states were practicing in nativist politics, but New York’s economic and political leaders viewed immigrant labor as a boon to the economy—and as a great resource worthy of protection. After all, the immigrants were the ones doing all the hard labor to build New York’s many railroads as well as the Erie Canal.

In effect, the Emigration Board created a quasi-socialist system that worked. Shipping companies paid a fee for each passenger out of fares received, and these monies provided for medical care, shelter, and, on occasion, monetary assistance as needed. The board supported immigrants who fell under hard times for five years after arrival, and it constructed hospitals and shelters on Ward’s Island. Naturally, not everyone was in favor of these handouts—some New Yorkers went as far as burning down structures that the board had purchased or constructed.

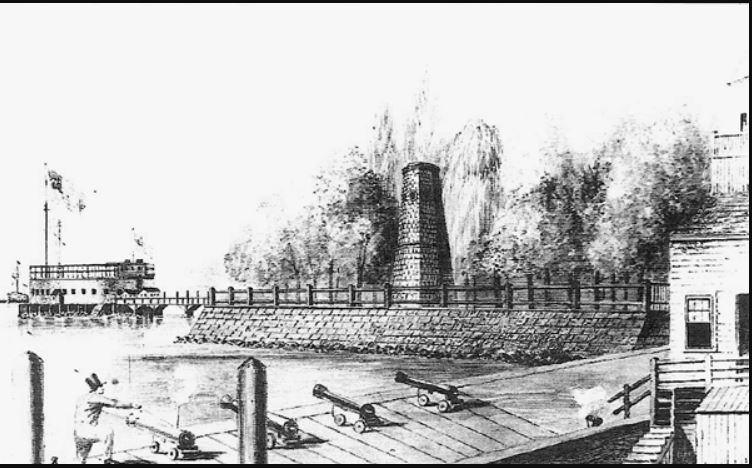

Ten years after its founding, the Emigration Board took possession of an old fort originally called the West Battery, which had been constructed on a small man-made island about two blocks west of the old Fort Amsterdam in 1811. The fort never saw action during the War of 1812, and was later incorporated into Manhattan Island when Battery Park was expanded with landfill. In 1817, the fort was renamed Castle Clinton in honor of DeWitt Clinton, governor of New York.

Designed by architects John McComb, Jr. and Jonathan Williams, the old West Battery was located on an artificial island just 300 feet off the southern tip of Manhattan. A long bridge connected it to the mainland.

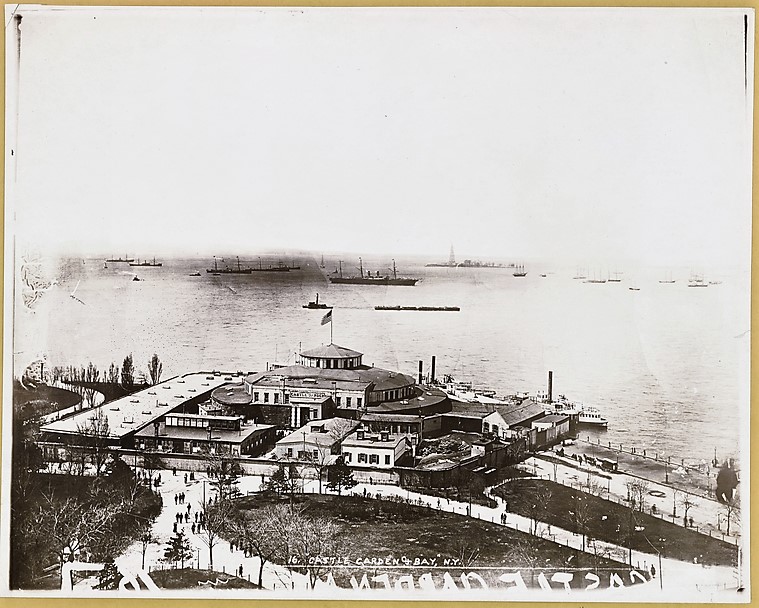

In 1823, the fort was deeded to New York City. The structure served as a public leisure center and restaurant called Castle Garden where vendors sold lemonade and ice cream, and later, when a roof was added around 1840, as a venue for Italian opera.

In 1855, a year after the Castle Garden’s lease had expired, the Emigration Board took over the building with some help from the New York Central and Erie railroads, which paid the monthly $10,000 rent in exchange for exclusive rights to sell tickets to the immigrants. Castle Garden processed its first three shiploads of steerage passengers on August 3, 1855 (most first- and second-class passengers were allowed to bypass inspection).

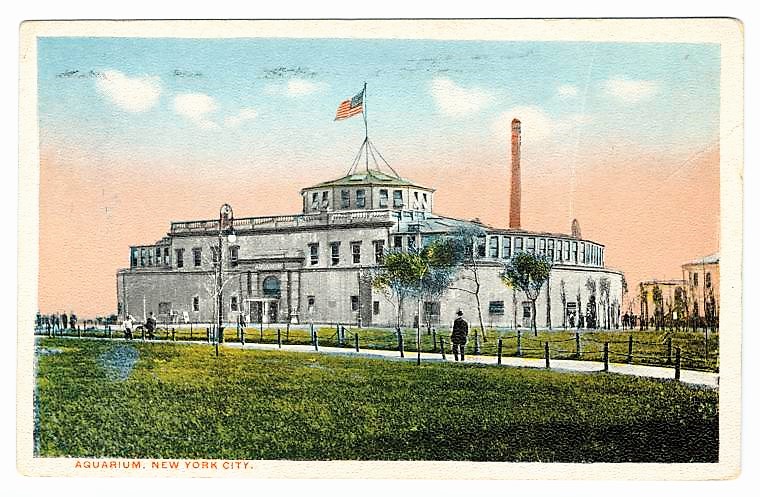

After Congress federalized immigration control in 1882, the U.S. Treasury Department subcontracted the Emigration Board to operate Castle Garden for eight more years. In 1890, a federal inquiry determined that the depot was inadequate and ordered its closure. Immigration processing was moved temporarily to the United States Barge Office at Battery Park until the all-wood, tinder-box facility at Ellis Island opened in 1892.