Most of the cat-women stories of Old New York were of two genres: outlandish tales of the proverbial “crazy cat lady” who had a dozen or more cats in her house or newsy stories about women who bred cats on a professional basis to sell to wealthy Victorian ladies or to show at the various New York cat shows.

The following cat story set on Fort Greene Place in Brooklyn falls under the former category.

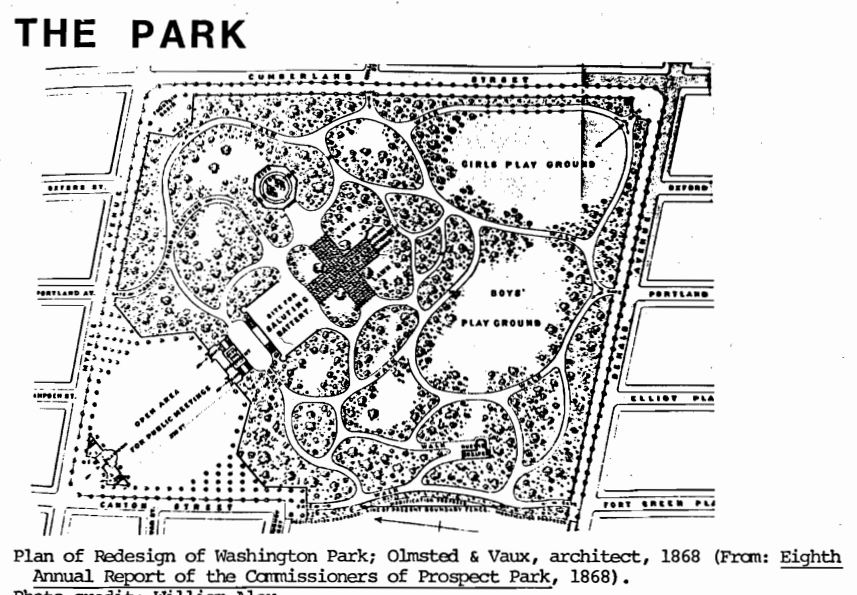

Originally the site of forts built for the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, Fort Greene Park began serving as a public recreational space for local residents shortly after the threat of the War of 1812 passed. By 1847 it was designated Brooklyn’s first park (called Washington Park). Famed landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux began designing a new layout in 1867, and in 1897 the park was renamed Fort Greene Park for Major General Nathanael Greene.

Lubomir Peter Saponapf was born in Bulgaria sometime around 1885. He and his German-born wife, Frieda, married on July 12, 1919, and moved into an brownstone apartment at 12 South Elliott Place, just a few doors away from Fort Greene Park.

Lubomir worked as the head of the Royal Stair Cushion Company at 303 Schermerhorn Street. Frieda worked as a nurse. They did not have children (Frieda was older than Lubomir and was about 40 when they married), which allowed them to operate their home as a boarding house for lodgers.

By 1924, when this story takes place, the Saponapfs had purchased a three-story Italianate-style row house with basement at 67 Fort Greene Place. Lubomir bought the carpet business, joined the art staff of a local newspaper, and began painting and designing magazine covers on the side.

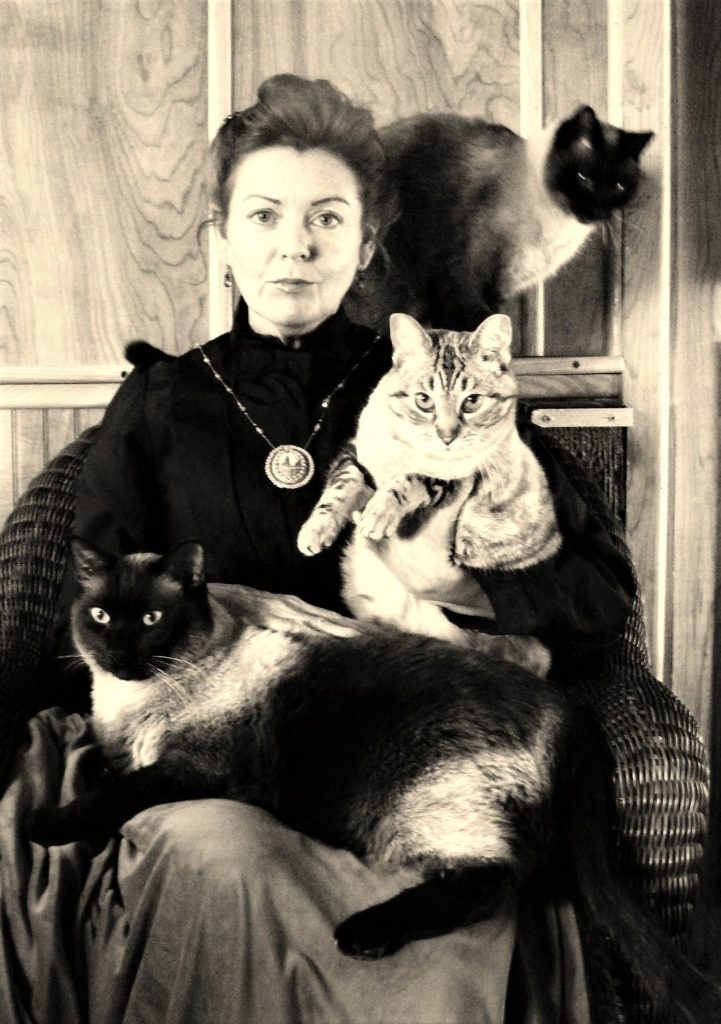

Frieda ended her nursing career and began spending all her time with her cats–all twelve of them. She purchased them special food and even allowed the stray cats to sleep in the bed.

In March 1924, Frieda filed a separation lawsuit against her husband on charges of indifferent treatment and abandonment. The case, in which Frieda sought alimony and counsel fees, made its way to the desk of New York Supreme Court Justice Edward Lazansky.

“The Old Ford No Longer Answered the Purpose”

In her affidavit, Frieda said her husband’s attitude had changed

after he became successful as an artist. He began to find fault with her and leave her alone more often.

With the rise of his fame as an artist and the acquisition of the sole ownership of an old and prosperous business, his conduct toward me changed. New worlds and visions had opened before his eyes. I was discarded and cast aside. Fault-finding became a ruling passion with him. He managed to find company elsewhere, and I had to live alone. The old Ford no longer answered the purpose; it was replaced by a high-powered car.”

Lubomir denied all his wife’s charges and countered with the story of his wife’s devotion to cats. According to Lubomir, Frieda kept about a dozen cats, which took over several rooms in their home and rendered the house “distasteful” to him. He said he gave her a choice: either the cats go or he moves out. The cats won.

It became impossible for me to continue living with my wife because of her desire and determination, in spite of my opposition, to acquire, nurse, keep and maintain cats of every kind, form and description. My wife would go hither and thither through the streets and pick up and carry stray cats to our rooms. My wife refused to give up her cats but even permitted two or three of her favorite ones to lie in bed with her at night.

She had as many as twelve cats at one time in our two or three little rooms. She refused to part with the cats. I, therefore, knowing she had a prosperous rooming house business, determined to leave her with her cats, as there were no children, and I knew she was amply able to care for herself. She had no rent to pay, it being my house, and I quite the premises.”

Lubomir Made Name Plates for the Cats

This is not Frieda, but Frieda was truly a crazy cat lady. Not only did she hoard cats in her home, she admitted that one time she chloroformed three kittens and placed the dead kitties on her husband’s picture canvas so that he could use their whiskers to make a fine paint brush.

Frieda countered her husband’s affidavit in court by telling the judge that Lubomir also loved the cats and enjoyed playing with them. She said that it was her husband, in fact, who had brought the first cat to their house. “He even made name plates for them. See, ‘Gerry, 67 Fort Greene Place.’ He liked yellow cats best.”

Justice Lazansky denied Frieda’s application for alimony, but he did allow her $75 for counsel fees.

According to the 1925 and 1930 census reports, Frieda and Lubomir were still separated. Frieda continued to operate a boarding house at 67 Fort Greene Place (at one time she had about 10 boarders) and Lubomir moved in with his brother and his family nearby at 32 S. Elliott Street.

The brownstone at 67 Fort Greene Place was sold by the Brooklyn Trust Company in 1939. I’m not sure if the sale included all the furniture and the cats or not. I wonder if any cats live there today?

A Brief History of 67 Fort Greene Place

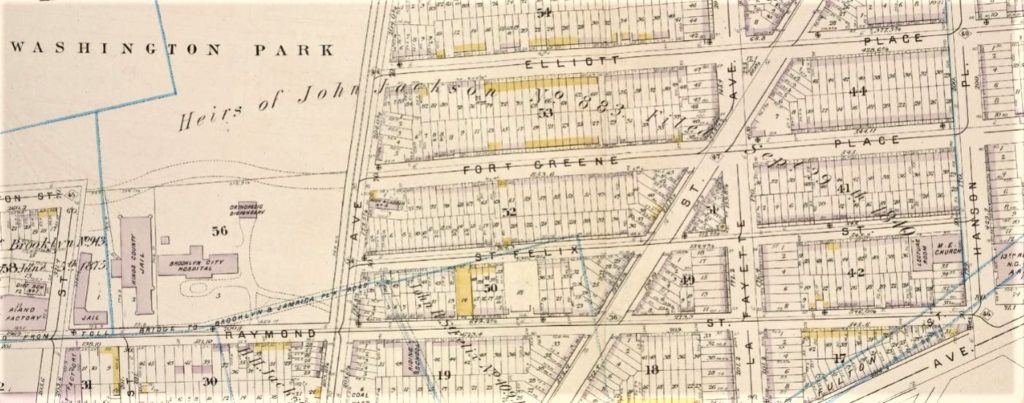

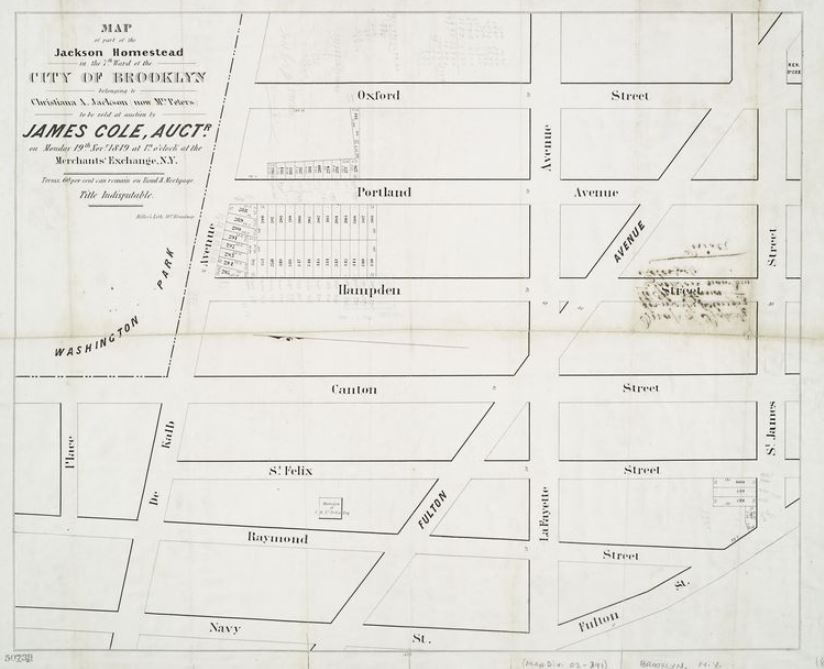

The three-story brownstone at 67 Fort Greene Place was constructed sometime around 1900 on the site of a large parcel of land once owned by Christiana A. Jackson, the daughter of shipbuilder John Jackson and Sarah Udall Jackson. This parcel was one of the 150 lots sold at two separate auctions in 1847 and 1849. (The second auction took place following the death of Christiana’s husband, William Peters.)

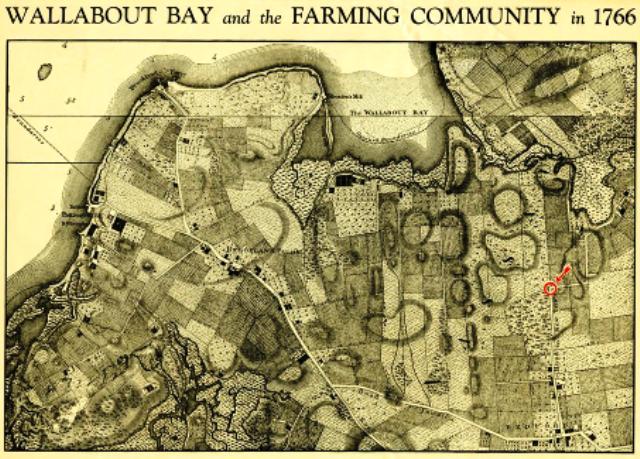

The ownership of this land goes back to the seventeenth century, when it was the property of Pieter Ceasar Alberti (reportedly Brooklyn’s first resident of Italian descent). By the nineteenth century, much of the Fort Greene neighborhood had been divided into four farm tracts owned by members of the Ryerson, Post, Spader, and Jackson families.

The Jackson tract dates back to 1791, when John Jackson and his brothers, Tredwell and Samuel, acquired a 30-acre estate south of present-day Dekalb Avenue between South Elliott Place and Carlton Avenue. Around this same time, the brothers also acquired a 100-acre crescent-shaped tract along the Wallabout Bay from the Commissioners of Forfeiture.

There, they took advantage of the existing dock on the property to construct their own small shipyard and about ten houses for their workers. (Today the Jackson lands are part of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.)

Prior to 1859, Fort Greene Place was called Canton Street. In 1859, Mr. Lake and other residents of Canton Street got an act passed changing the name of the street between Atlantic and DeKalb to Fort Greene Place in order to prevent the name Fort Greene from becoming “obsolete and the revolutionary reminiscences it recalls passing into oblivion” after Fort Greene was renamed Washington Park.

“This will preserve the name and also give a distinct designation to a very elegant and well located street.”– Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 25, 1859