Fanny Jane McAdam–aka Jane McAdam, Mary Jane McAdam, and Henrietta Snowden–had a reputation on the Lower East Side. Her neighbors in the three-story brick boarding house at 101 East Broadway called her a witch for her angry outbursts and physical attacks on them. The police knew the slender, tall lady (she was over six feet tall) as a problematic woman with a long rap sheet for disorderly conduct.

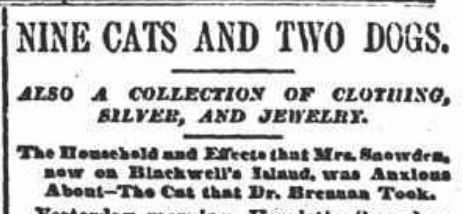

Her two dogs—Spitz and Flora—and nine cats knew her as the lady who took care of them and bejeweled them with coin-laden leather collars. They trusted her to feed them and provide water every day. That’s why she was determined to ensure their care when she was sentenced to prison for six months in February 1879.

The saga of Jane McAdam begins on February 11, 1879. That’s the day she stole a door mat from the residence of Officer Henry Q. Howe of the 26th Police Precinct.

Jane had been taking a stroll uptown when she noticed the decorative mat in front of 359 West 31st Street. A pawn dealer had told her he would offer her money for such an item, so she grabbed it. Unfortunately, Officer Howe caught her in the act and arrested her.

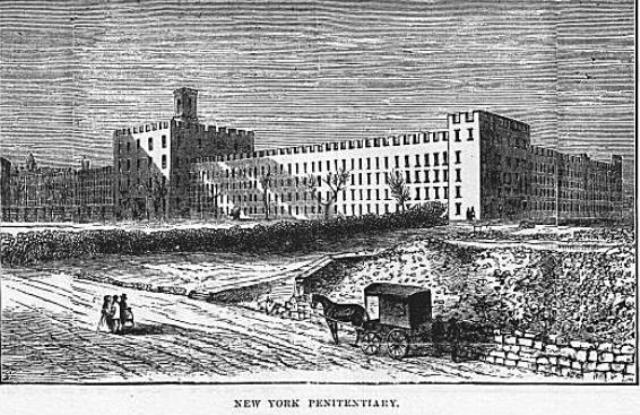

A few days after she arrived at the women’s prison on Blackwell’s Island, Jane wrote a letter to Henry Bergh of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). She begged him to come to Blackwell’s Island to get the key to her room, which was in the attic of the boarding house on East Broadway.

Jane told Bergh that she had many valuables in her room, including some cash for someone to take care of her pets.

By this time, the two dogs and nine cats—including 4 newborn kittens—had been stuck in the attic room on East Broadway for several days. Neighbors who heard their howls and meows pushed meat through a fanlight in the door. They also also lowered a bowl of water through the same small aperture.

At last, officers Smart and Lambert from the SPCA obtained the key from Jane. Accompanied by Captain McElwain of the Seventh Precinct police station on Madison Avenue, prison Warden Fox, and a dog fancier that Fox had made arrangements with to care for the animals, the SPCA officers entered the small room. The men must have froze in disbelief at what they saw.

Scattered all over the floor were valuable pieces of undergarments, stacks of chinaware, five trunks filled with silverware, and large quantities of jewelry, much of it in the original packaging. A large amount of cash—about $12—was also in the room. There was no real furniture in the room, save for some sleeping baskets for the pets.

The men also discovered a white dog named Spitz, a yellow dog named Flora, five adult cats, and four kittens. All of the animals wore leather collars laden with old Chinese coins and English sixpennies. One cat wore a collar embroidered with small Mexican silver pieces.

As the men began rounding up the animals for the dog fancier, Dr. Edward M. Brennan, who occupied a room directly across from Jane’s room, stopped by to take one of the adult cats. The other adults cats were placed in baskets, “but not without some very energetic resistance on their part.”

Sadly, the poor little kittens did not have a happy fate. According to the New York Sun, the kittens were “condemned to suffer death in as painless a way as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals can devise.” (The Brooklyn Union poured salt in the wounds by stating that while the adult cats and dogs were being well treated, “the kittens have paid the penalty of their youth and uselessness, and will never be afflicted with the life that cats are heirs to.”

(On a happier note. it was also reported that two “fashionably dressed women” called at the SPCA office on Fourth Avenue and 22nd Street to check on the kittens. One of the women left a request for Mr. Bergh to send her a coal-black kitten from the litter. Hopefully the other kittens were also adopted by some kind people.)

The Stash of Chinaware and Silverware at 101 East Broadway

After scanning the contents of the room, Warden Fox began making arrangements with Mr. Alexander, who owned the building, to take an inventory of Jane’s property. But when Captain McElwain found out that Jane had been arrested for petty larceny (and not for disorderly conduct) he took charge of the property. He needed to investigate whether or not it had been stolen.

Here is a list of the property, which was reportedly worth between $2,000 and $3,000:

6 butter dishes, 4 teapots, 2 milk pitchers, 1 sugar bowl, 3 mugs, 1 castor, 3 saltshakers, 8 oyster pans, 34 teaspoons, 17 tablespoons, 24 forks, 3 knives, 3 butter knives, 4 mustard spoons, 5 barroom spoons, 3 salt spoons, 2 sugar spoon, 2 berry spoon, 2 gravy ladle, 2 strainer. All of these items were silver plated and bore no marks.

There were also 6 knives with silver handles worth about $15 and 1 teapot, 2 teaspoons, 2 forks, and 2 knives, all marked “St. James;” 1 milk mug, 6 tablespoons, 3 forks, 2 knives, and 1 salt spoon, all marked “Central Park Garden;” 3 spoons marked “Amphytryon;” 2 spoons marked “Glenham;” 1 spoon marked “A;” 2 spoons marked “Nancy;” 1 spoon marked “A.J.D.;” 1 spoon marked “M.M.;” 1 sugar spoon marked “Bath Hotel;” and 1 knife marked “J.M. Shaw.”

The following day, Captain McElwain sent Sergeant Lonsdale to Blackwell’s Island to speak with Jane about the property. The sergeant had some difficulty finding her at first, because she had lied and said her name was Henrietta Snowden. On top of that, the court had sentenced her under the name of Henrietta Snowman.

Sergeant Londdale also did not recognize Jane when he first saw her. As the New York Times reported, “Instead of a dirty, ill-clad, gypsy-looking hag who had been arrested, he saw before him a woman clothed in a neat, though coarse prison dress with clean face and hands and carefully combed hair.”

According to news reports, Jane told the officer a “wild, rambling, and at times romantic story” when he questioned her. She said she was single, but that she also had a husband who had served as a paymaster in the US Navy. When he left her, she said, he stole $2,000 from her. This left her destitute and forced to take on a job as a steward of a steamship.

Jane also told the sergeant that she had once been very rich and powerful, and that she had traveled to many countries, including China, France, and England. She said she could speak fluently in five languages, and that she had once lived in Boston.

Sergeant Lonsdale was also able to obtain some important information that he thought could help in the investigation of the stolen the property now in her possession. According to Jane, she had received the china and silverware from three servant girls–Margaret Taylor, Johanna Barrett, and Eliza Murray. She had provided lodgings to these destitute women while she was living at 1 Battery Place; the women paid her with the china and silverware.

While Sergeant Lonsdale was interviewing Jane at Blackwell’s Island, Captain McElwain gathered additional information from Dr. Brennan, who had taken one the cats.

Dr. Brennan said Jane was 45 years old and had arrived at 101 East Broadway a month earlier with five trunks. She immediately started accusing her neighbors of stealing her property. John Clark, the home’s housekeeper, had her arrested.

The doctor also said her cats and dogs were “an abominable nuisance.” One day, he said, Flora walked into his room and stole a chop that he had just cooked from his table. He kicked the dog with his boot, which sent Jane bursting into his room.

Jane attacked Dr. Brennan and even threw an oil lamp at him, which hit the door as he was closing it. The doctor told the police captain that the cat he had adopted from Jane’s room snored and kept him awake night. (Good kitty.)

I don’t know what happened to Jane and her pets after she left Blackwell’s Island. Let’s hope her story had a happy ending.

A Brief History of East Broadway

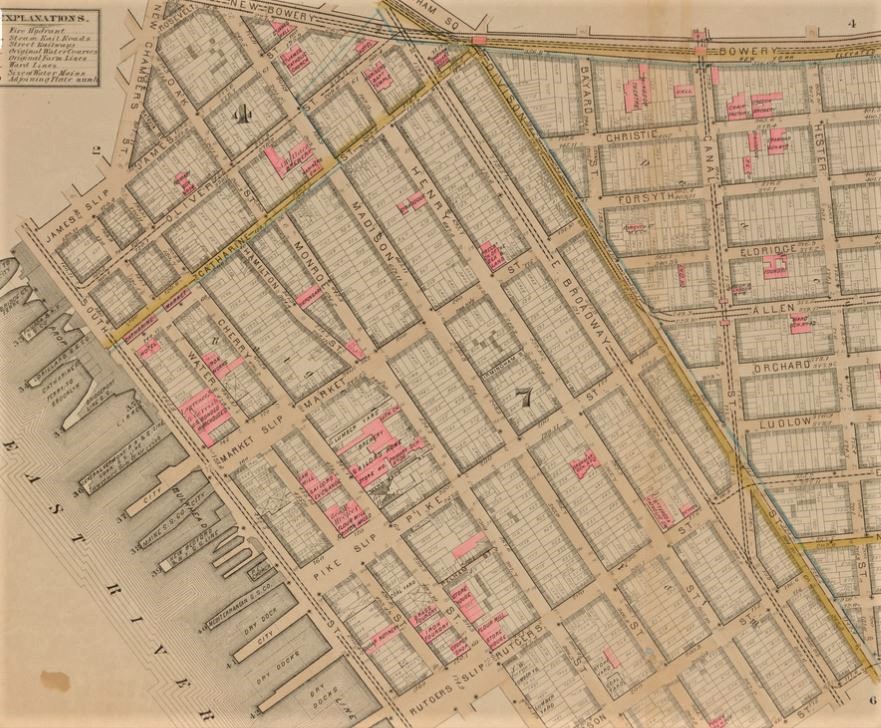

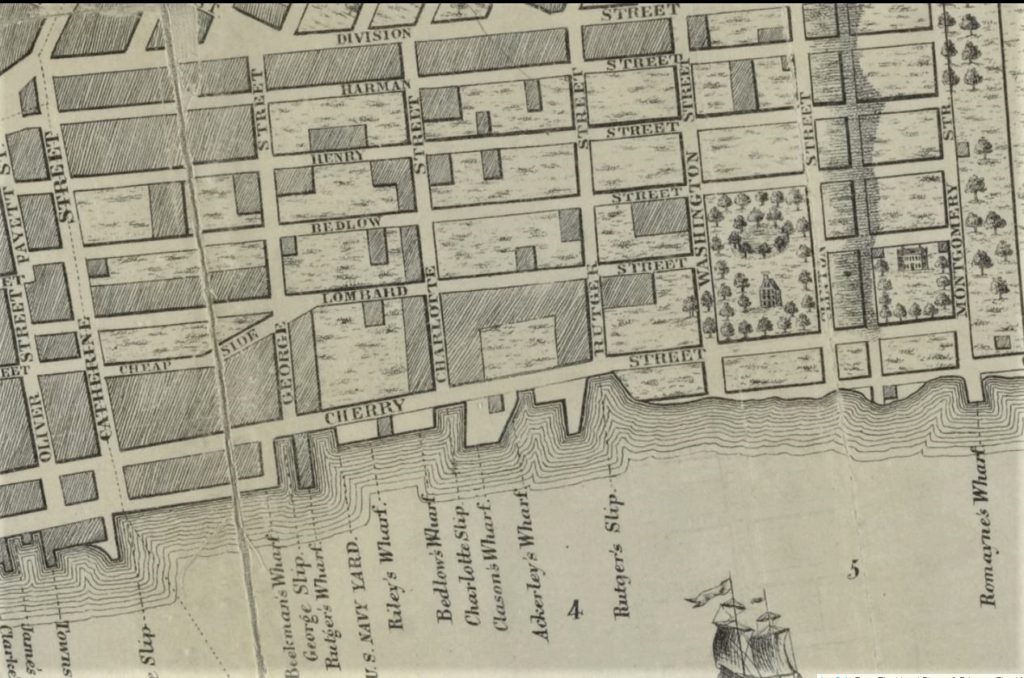

Prior to 1831, East Broadway was called Harman Street, in honor of Harmanus Rutgers (1663-1753), who owned a large, 100-acre farm in the Lower East Side along the East River.

The Rutgers farm comprised the 57-acre Bouwery No. 6 (formerly owned by the Dutch West India Company) and a parcel of upland along the East River just south of that bowery. It also included some land east of Catherine Street that was originally part of Wolphert’s Meadows (Wolphert Gerritsen was the first recorded owner of this land, dating back to 1630).

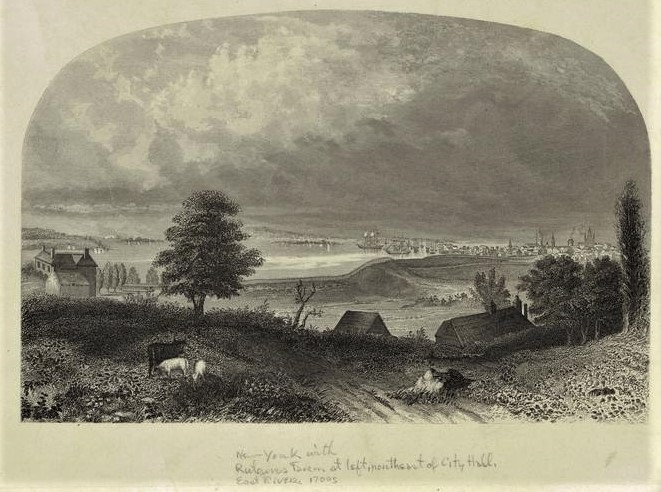

The farm was located in the city’s “out ward,” a sprawling area of the island that for decades remained a rural land of hills, marshes, gardens, and woods. New York Public Library Digital Collections

Hermanus and his wife, Catharina Meyer Rutgers, acquired the land in 1728, about 38 years after they had relocated to Manhattan from Albany. Hermanus was a descendant of Rutger Jacobse (d. 1665), who emigrated in 1636 from the village of Schoenderwoerdt in the Netherlands to Fort Orange (Albany) in the colony of New Netherland. The Rutgers made their fortune in brewing alcoholic beverages.

In 1753, the large farm passed onto Hermanus and Catharina’s son, Hendrick Rutgers (1712–1779), and his wife, Catharine DePeyster (1711–1779). Over the next 20 years, Hendrick built a large mansion (the original farmhouse was on the east side of Bowery Lane), a brew house, a malt house, a mill, a stables, and about a half dozen other buildings. He also laid out the farm in lots; by 1764, the farm had been divided into about 600 building lots.

The Rutgers Farm

The following account of the property comes from The Iconography of Manhattan:

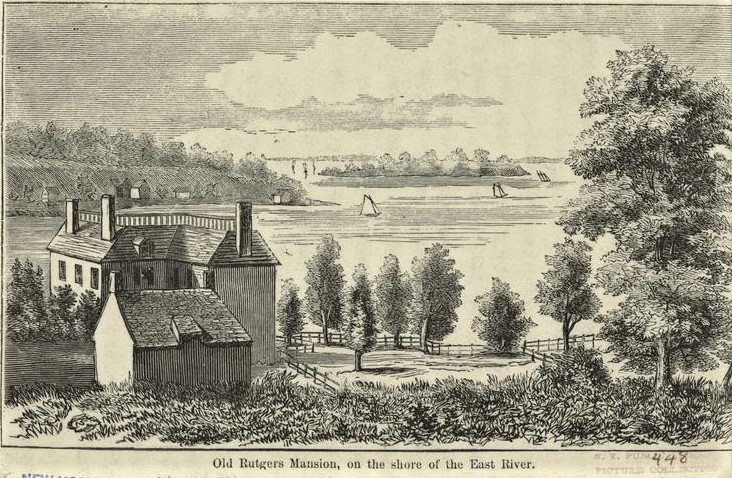

The house, the main part built of bricks said to have been brought from Holland (perhaps only a reference to size and bond), was erected in 1754-5 hy Hendrick Rutgers, who had a portion of his farm laid out in streets and lots, and, in 1765, agreed with James De Lancey on a boundary line between their farms, running along Division and Little Division (now Montgomery) Streets.

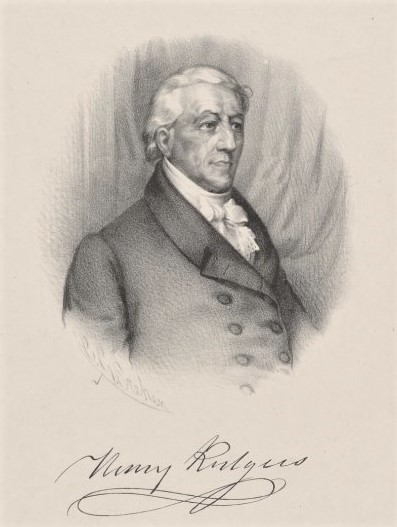

Rutgers died in 1779, and devised the farm to his only surviving son, Henry, including in his bequest the family mansion, which, during the occupation of New York by the British, was used as a hospital. At the close of the war, Colonel Rutgers, who had been active on the side of the colonies, reoccupied the homestead, and kept bachelor’s hall there until his death, nearly fifty years later.

He was a personal friend of Washington and Clinton and other prominent men of the period, and a benefactor of Rutgers College, at New Brunswick, N. J. (formerly Queen’s College), which was re-named after him in 1825. He died in 1830, leaving the greater part of the Rutgers farm, “including the mansion house and all the land attached thereto,” to his great-nephew, William Bedlow Crosby.

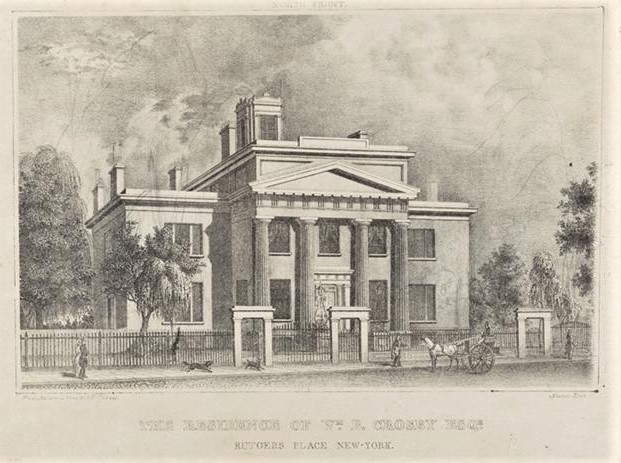

After Col. Rutgers died, Mr. Crosby had Monroe Street carried through the two blocks bounded by Madison, Cherry, Jefferson, and Clinton Streets, then surrounding the house grounds, and this portion of Monroe Street was named Rutgers Place. The house was remodeled at this time, two wings being added, and its north side made the entrance front.

It stood thus, with a block of ground in lawn and garden surrounding it and the carriage house, stable, etc., until Mr. Crosby’s death, in 1865, when it was sold, and shortly afterwards torn down. Its site is now occupied by tenement houses—Nos. 288 to 314 Cherry Street.

During the Revolutionary War, the Rutgers mansion reportedly served as a barracks and hospital for British officers and Hessian fighters. The brew house and stable were used for British naval stores.

Sadly, not only did the brew house burn to the ground; the gardens and crops were ruined, the trees were cut down, and the other buildings and fences were broken down for firewood.

The Demise of the Rutgers Farm and Mansion

Following the war, Henry began selling long-term ground leases to tenants, who built their stores, shops, and homes on Harman (East Broadway), Henry, Madison, and Monroe Streets. He also set off some of the land near Chatham Square for charity purposes (eg, for the construction of churches and schools). By about 1800, Henry’s own private property was reduced to about two city blocks.

Henry Rutgers died at home on February 17, 1830. He was initially buried in the Reformed Church cemetery on Nassau Street and then later removed to the Middle Church cemetery in Lafayette Place. In 1865, he was re-interred in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn.

In January 1831, the newspapers reported that Harman Street had been renamed East Broadway. That year, the widow of Dr. Valentine Seaman occupied the home at 101 East Broadway. Ten years later, in 1841, the house where Jane McAdam would live with her cats and dogs many years later was advertised as a private home with a few select boarders.