New York Sun, June 30, 1907

When I discovered this Brooklyn cat story while doing research for my story about political cats Lem and Tiger, I couldn’t stop smiling. The story was so colorfully written! And the history of the old Bedford Corners is fascinating, too.

I realized I would have to share most of the old news article word-for-word so that my readers could enjoy it as much as I did. I could not do it justice by paraphrasing the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter.

The story is rather long (almost two full columns of newsprint), so I’m going to break it up into two parts. I’ll incorporate a brief history of Bedford Corners into both sections to set the scene and provide additional information for those who are interested in exploring the history of the neighborhood in which this fabulous feline story took place.

18th-Century Bedford Corners

Before I share this delightful story of spilled milk set in 1907, let’s go back in time another 110 years. Prior to the late 1800s, much of the area along the old King’s Highway between today’s Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights comprised open fields, woodlands, and large farms owned by some of Brooklyn’s oldest families of street-name fame, including the Remsens, Lefferts, and Brevoorts.

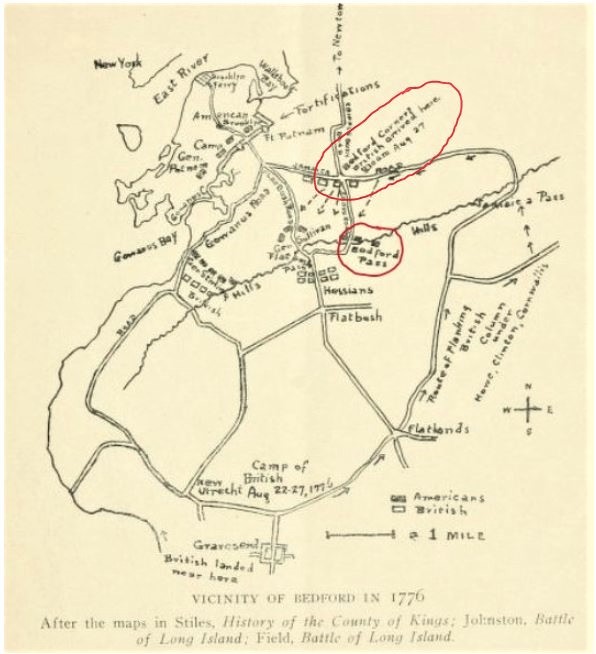

Back then, the area was an independent hamlet of Breukelen called Bedford. The hamlet, which featured prominently during the Battle of Long Island in 1776, was likely established during the last years of Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s administration (1647-1664). Bedford Corners, illustrated above, was at the center of Bedford.

Bedford Corners had a 17th-century tavern and a cluster of 17th- and 18th-century Dutch houses, many of which were occupied by members of the Lefferts family (more on this in Part II). Following the Revolution, Bedford Corners became a thriving village that served as a midway point for people traveling between Flatbush, Long Island, and the Brooklyn waterfront.

A September 1897 article and interview with John Lefferts Jr. in the Brooklyn Citizen summarizes late 18thh-century Bedford Corners:

It is afternoon, Sept. 9, 1797. A farm-dog barks lustily on Bedford Corners, at a casual passer-by. A quiet country scene, interspersed with a cluster of old colonial houses, greets the view. The squirrel trickles through the stone fences, by the Cripple Bush road; the clearings in the woods are tinct with the songs of birds; the brush fires burn in the fields dotted with turbaned slaves; the red Indians in small squads still come sometimes about the place; the white covered wagons wind slowly along the dry dusty country road, to the small town on the bank of the river;

no ferry, save a rude one; no telegraph, no trolley, no electric motor, no modern improvements of any kind whatsoever; no policemen, no pavements, no taxes, worth disputing; no intermixture of races as yet, save the English and the Dutch, and only Dutch just about here; no small holdings, but everything on a large scale; no newspapers worth recording, save occasionally a New York, English or Holland packet; no news, save that one Dutch family had married into another; no noise, save a gun discharged at the game, or wild fowl that infested the island;

no adulterated brands, but plenty of good living and Holland hospitality, and well-to-do thrifty and tanned farmers, whose great-grandchildren have left the fields where their fathers ploughed the red coppers out of the red furrows, and no danger, save from mosquitoes, if your blood was bad, and no watchman’s rattle, save a rattlesnake. Such was Bedford Corners in 1797.

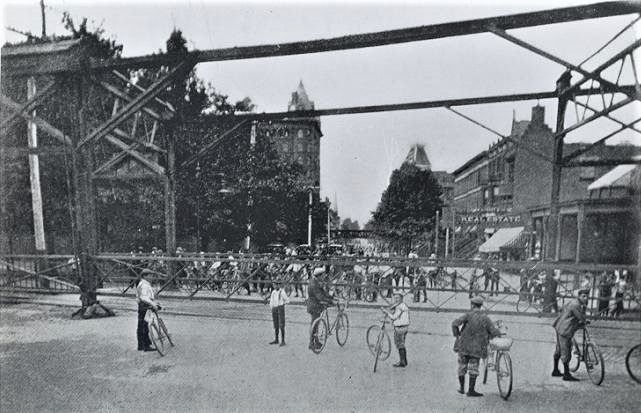

One hundred years later, at the intersection of Bedford Avenue and Fulton Street, only two of the old houses were still standing. As the Brooklyn Citizen reporter noted, a century of progress had reared its ugly head at Bedford Corners.

Elevated trains now “thunder by faster than at any other time” above while the “trolley cars tread on each other’s heels as they run the gamut of the chromatic scale on the gleaming wire,” the reporter said. An endless procession of horse-drawn vehicles and “wheelpeople” on bicycles jockey for space on the thoroughfare.

In an endless attempt “to save life and limb from a terrible fate,” police officers Henry C. Frohne and Andrew Wooldridge pluck people wedged between cars and carts, chase after frantic, runaway horses, and grab children before they step off the curb…

1907: Trolley vs Milk Truck

With all this activity going on, it’s no surprise that a milk wagon was struck by a Bergen Street streetcar only a few blocks from the dangerous Fulton-Bedford intersection. It’s also no surprise that the accident attracted a large crowd of active feline spectators.

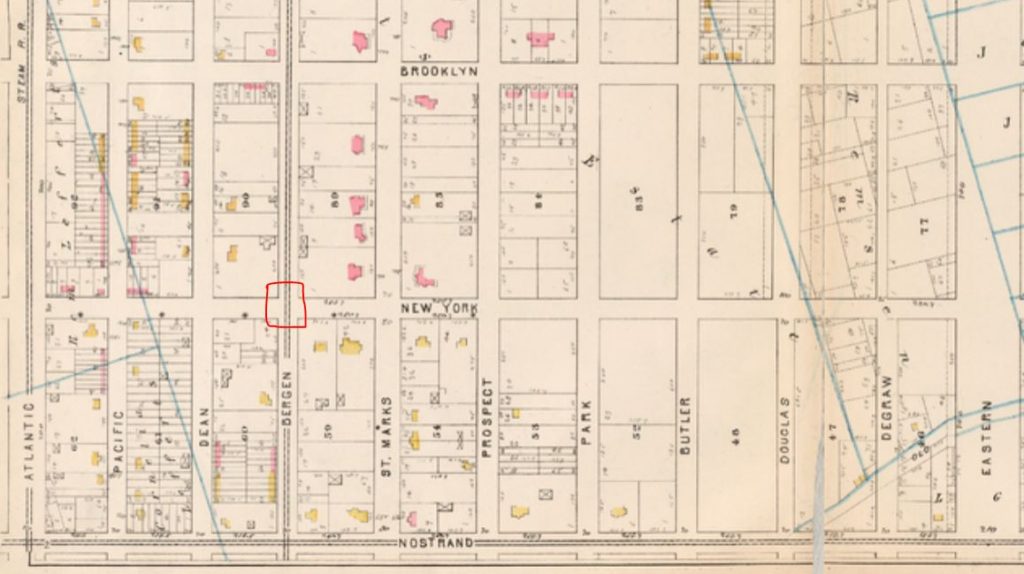

On Saturday morning, June 29, 1907, Charles Wolfert was driving a milk truck owned by William Evans of 250 Herkimer Street when he was struck by a streetcar on the Bergen Street line. The impact tossed Wolfert to the ground, causing him to sustain a scalp wound and bruised wrist.

The violent impact also overturned the wagon, sending all the glass milk bottles to the hard pavement. Within seconds, gallons of milk began pouring into the intersection of Bergen Street and New York Avenue on the northern edge of what is now the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn.

A Dream Come True for Street Cats

From this point on, I will be quoting directly from the colorful article from the Brooklyn Citizen:

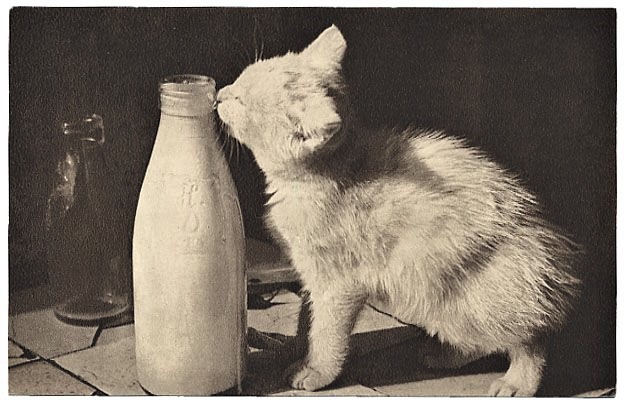

A vagrant cat was about the cross the street when she was stopped at the brink of the white lake. She looked, smelled, than snarled at what she thought was a hallucination brought on by an empty stomach. She looked and smelled again, and to enjoy the vision even it was a dream she literally fell into it. It tasted like milk and she found the ocean a reality. Other feline tramps saw her apparent enjoyment and went to investigate the cause. The same doubt possessed them until they tasted the fluid and then they followed the example of the first cat.

From near and far, more of them arrived on the scene. The first arrival greeted the newcomers with evident displeasure. The instinctive selfishness arched their backs, bristled their fur and made their tails appear as brushes, but as the supply seemed unlimited and time was fleeting, they applied themselves to the work.

Working their way inward from all the sides were cats of every description. Spotted cats, cats with Tammany stripes, cats of maltese color, cats of jetty black, and others of spotless white, cats whose outer skin hung close to their ribs and others who showed more plumpness; cats who eked out their daily sustenance by thievery and those which were cast on their own resources by the family leaving for the summer, all were busily engaged in stemming the flood of the white fluid.

The pungent sweetness of the milk permeated the air, and the house cats in the neighborhood sat up and sniffed. Sniffing brought temptation, and cats who had never before strayed from the paths of rectitude stole out to “The Great White Way.” Kitchen corners were deserted, the pussies came forth from under the bed and off the chair. The solaces of old maids forgot everything to wander out whence to the place where the smell arose. In all the finery of belled collars and pink and blue throat ribbons, they left their homes and joined other wayward Toms and Tabbies.

Those already on the scene gazed with indifference at the pampered new arrivals and after blinking a welcome made room for them. A beautiful Angora with silky fur crowded in between two mangy tramps, and another of dreamy eyes took his place beside and old and grizzled survivor of flying missiles. In the plenitude of the fluid there was enough for all, and time was too precious to spend in fighting.

The purring murmur of contentment sounded the dull hum of machinery. Shades of Dick Whittington’s puss and holy cat of Babastas! Had ever such good fortune come upon earth since the golden pagan days when the cat tribe was deified?

At last their midnight-directed orisons had been heard.

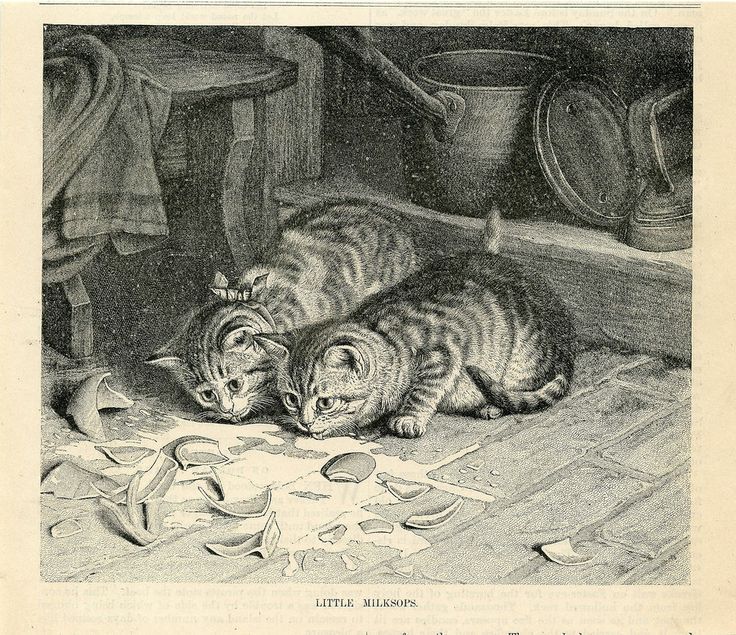

The ecstasy of it began to become commonplace. They waded in the milk, they wallowed in it, they rolled, they reveled in it, they rioted in it. One of them became so tired of the mere pleasure of it that she rolled over on her side and continued to her lapping….

Stay tuned for Part II, in which I will finish this tale of spilled milk and explore some more history of Bedford Corners.