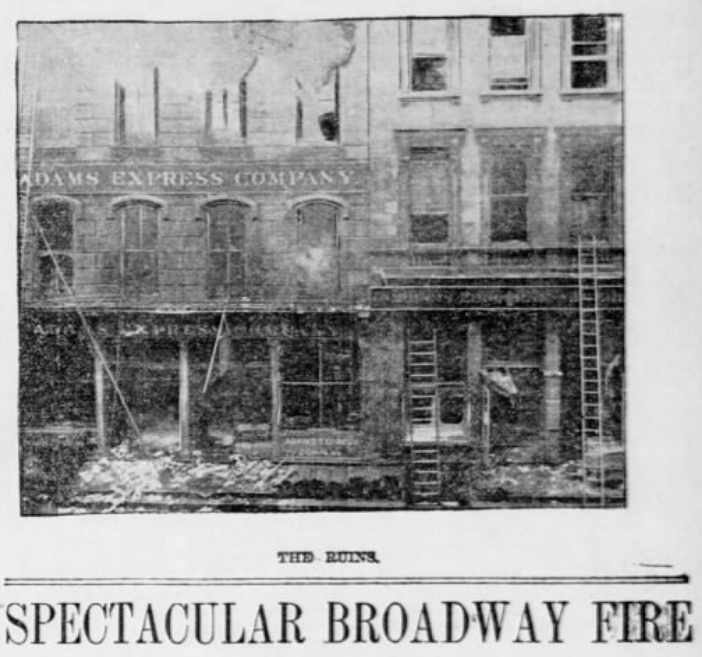

On Saturday, March 26, 1904, a fire gutted two large office buildings at 59 and 61 Broadway. The buildings were occupied by the Adams Express Company (#59) and the Morris European and American Express Company (#61). Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency was located at #57 and Wells-Fargo was at #63-65 Broadway.

Although the fire was not nearly as large as other city conflagrations, the Fire Department sounded the “two nines” alarm, to which every engine and truck south of 58th Street responded. A total of 32 engines, 10 trucks, and two water towers responded to the 11:00 a.m. blaze, which was extinguished in about two hours.

The fire, which started in the basement of 61 Broadway (possibly due to a careless employee with a lit cigar or matches), destroyed or damaged most of the Adams Express Company’s waybills, records, and other papers. All the currency, bullion, and other valuables in the fireproof safes and strongboxes were salvaged, albeit, water damaged.

Included in the saved items was a box containing numerous artificial skulls belonging to a theatrical company. The life-like skulls presented a ghastly sight when they fell out of the box and scattered along Broadway as the firemen were hosing down the building.

Although no civilians were killed or severely injured in the fire, six clerks—T. Edgar, J. Cavanagh, Henry Haas, Thomas Claire, A.J. Wilson, and James Schiebles–had to escape the burning building by tossing a rope fire escape out a second-floor window and sliding to the ground. Fireman Charles Beckingham of Engine Company No. 4 on Maiden Lane was injured when he was struck by falling glass. Other firemen just barely escaped injury when the rear wall of #59 collapsed onto Trinity Place.

Smoke the Fire Dog

One other “firefighter” injured during the incident was Smoke, a fire dog attached to Engine Company No. 32 at 108 John Street. Smoke was reportedly urging the horses to run faster when one of them kicked his right paw while the engine was approaching Wall Street.

Smoke limped into Wilson’s drug store, where he a clerk by the name of John Ralphs treated him for his injured paw. He then returned to his engine company and remained on duty for the rest of the day.

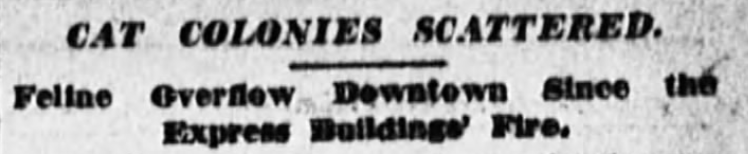

The Stranded Cat Colonies of Express Row

One week after the Adams Express fire, cats of all colors and sizes began prowling around the financial district. Tenants in neighboring office buildings, occupants in boarding houses on Greenwich Street, and tenement dwellers west of Trinity Church all started receiving visits from these strange cats, who were in turn tried to make new deals to be adopted and furnished with food and lodging.

This overflow of felines puzzled most people, who were not aware that a large cat colony was on the payroll of Adams Express and all the other big express companies occupying the buildings of “Express Row.” The cats lived in the cellars and sub-cellars of these buildings, and prior to the fire, most of them had never seen the light of day before.

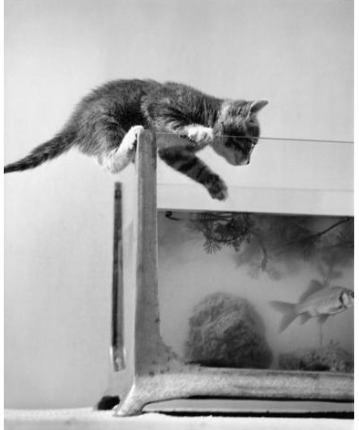

Just like the feline police force of New York’s Post Office, the Express Row cats were responsible for keeping the rats and mice at bay. Thousands of waybills between shippers, express companies, and railroad officials were stored in the cellars, and it was the cats’ job to keep the rodents away from these important papers. As The New York Sun noted, “One healthy rat with a voracious appetite to banquet on waybills would cause all kinds of trouble.”

In addition to their rat duty in the cellars, the cats were also responsible for patrolling the stables in the rear of the office buildings. These stables were breeding grounds for rats and mice, so a full complement of cats was needed for this job.

The Cellar Cats

Most of the Express Row cats were cellar-born, and thus, could start training during early kittenhood. On those rare occasions when the feline workforce started to decline, street cats were recruited from the outside world. It was the janitors’ responsibility to feed the cats at regular intervals, and to ensure the supply of cats did not diminish.

The cats employed at Adams Express and other shipping companies were all feral, so they often frightened the young clerks who had to venture into the dark underground storehouses in search of waybills.

Cats such as Speckled Pete, the Bold Trapper and Wild Bill, the Avenger took their jobs seriously, and did not appreciate when the young clerks entered their territory. Several clerks had to learn their lesson the hard way.

According to The Sun, all of the Express Row cats had escaped the burning buildings unharmed, but they were now scattered throughout the neighborhood. The hope was that when the companies re-established their offices in new buildings, some of the cats would return to the force.

If the janitors had to recruit new street cats for the waybill departments, the plan was to “borrow” working cats from other express companies “to act as instructors in organizing a rat police force to keep away four-legged marauders.”

Considering the size of the new Adams Express Company building erected eight years later, I have a feeling many cats found employment in this new building.

This end the cat portion of this story. If you are interested in history, please continue reading. There is a fishy surprise at the end.

A Brief History of Adams Express and Express Row

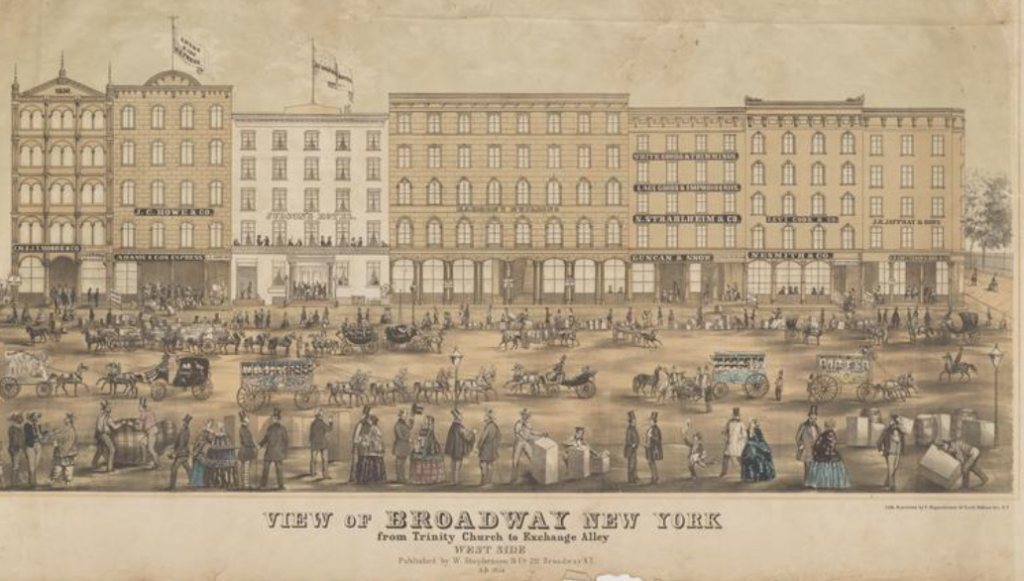

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the southern portion of Broadway between Exchange Alley and Rector Street was home to Adams Express, American Express, Wells Fargo, and other smaller express shipping firms. Most of the companies of “Express Row” occupied old, mid-19th-century buildings, which The Sun described as “seasoned tinder boxes.”

Adams Express began in 1839, when Alvin Adams, a produce merchant whose business collapsed during the Panic of 1837, began carrying letters, small packages, and valuables for clients between Boston and Worcester, Massachusetts. Adams quickly extended his territory to New York City (with offices at 16 Wall Street), Philadelphia, and other eastern cities.

The company moved into the Broadway offices sometime during the early 1850s.

Adams Express had many interesting clients over the years.

For example, abolitionist groups used the company in the 1840s to deliver anti-slavery newspapers from northern publishers to southern states. In 1849, a Richmond, Virginia slave named Henry “Box” Brown shipped himself to Philadelphia and freedom via Adams Express.

Following the fire in 1904, Adams Express continued to occupy the site on Broadway. In 1906, Adams Express began planning a new, fireproof building to be constructed on the site of 57-61 Broadway. The ram-rod straight, 32-story behemoth would be designed by architect Francis H. Kimball and have an official address of 61 Broadway.

When construction began in 1912, The New York Times and city planners expressed concerns about the skyscraper’s effect on sunlight and airspace. As with the Equitable Life Building (which was constructed a few years later after a fire destroyed the original building), they feared that the tall, straight building would block sunlight and cast shadows on nearby smaller buildings.

Unfortunately, construction began four years before the 1916 Zoning Resolution was enacted, requiring new buildings to have setbacks at certain heights, based on lot size.

The Fish at 61 Broadway

In 1998, Crown Properties purchased the 652,000 square-foot office building at 61 Broadway. At that time, the building was occupied by Merrill Lynch and MetLife. Oh yeah, and some fish.

According to Davar Rad, president of Crown Properties, the Adams Express building used to provide heat for surrounding buildings through huge boilers in its basement. The soot from these boilers was cooled by the high water table located directly under the building, which created a warm pool of water. The pool became a breeding ground for goldfish.

Apparently, a building engineer first spotted the goldfish in 1988, when Met Life purchased the building. Ten years later, the engineer was still feeding them through a trap door in the basement floor.

I can’t determine if the fish are still living under the building. Maybe we need to send in a few cats to find out and take a survey?