Cats in the Mews: July 19, 1904

On this day in history, the New York Times and numerous other newspapers reported on a Maltese (all gray) mother cat who was caring for her kitten and five orphan puppies in Brooklyn’s Kensington neighborhood. According to the Times, residents living near Avenue C and East 8th Street took great interest in the efforts of the cat to raise such a large, mixed family.

The story began a few weeks earlier at 402 East 8th Street, where Captain Samuel Fergusen Fahnestock of the 47th Regiment lived with his wife, Grace Louise Fahnestock (nee Kemp) and two daughters. Nettie, Mrs. Fahnestock’s bat-eared French bulldog, had just given birth to five healthy and handsome pups. Nettie was reportedly worth $900, so Mrs. Fahnestock had high hopes for the tiny bulldog puppies.

Sadly, the registered pedigree mother dog died two days after her pups were born. Mrs. Fahnestock and her friend, Mrs. Irving N. Dodge, tried feeding the orphan puppies with bottled milk, but the two women could not keep up with the pups’ voracious appetites.

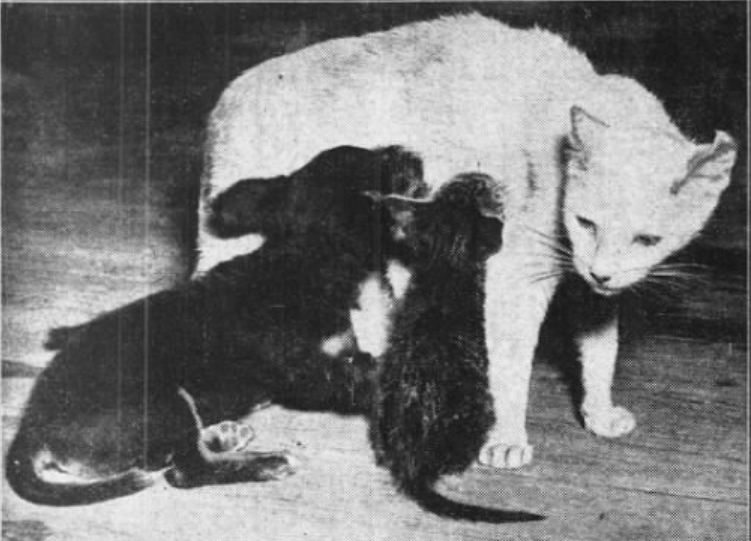

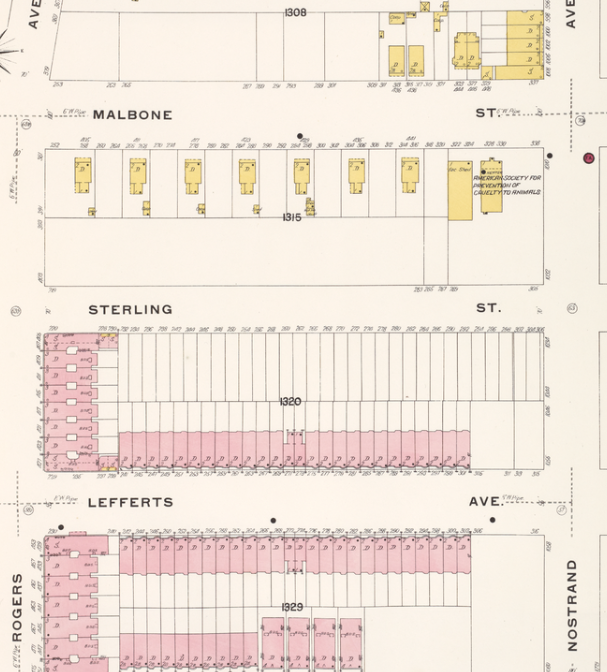

Mrs. Dodge suggested going to the ASPCA dog pound on Malbone Street (perfect street name for a dog pound) to find a canine wet nurse for the orphan puppies. Mrs. Fahnestock, the adopted daughter of James and Caroline Kemp, agreed to finding a foster mom to adopt the puppies.

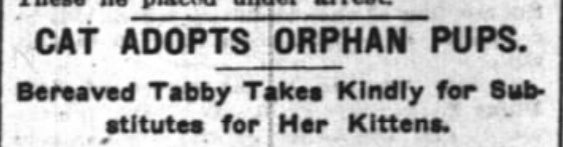

According to the news reports, the pound did not have a suitable dog to take on the important job. However, the superintendent remembered a stray cat that had recently been dropped off at the shelter with her newborn kittens.

He explained to Mrs. Fahnestock that all but one of the kittens had died, and the mother cat appeared to be grieving deeply over her loss. He thought she would accept the motherless puppies and nurse them.

Mrs. Fahnestock agreed to the experiment, and welcomed the mother cat and kitten into her home. The puppies accepted their new feline mother right away. The mother cat, in turn, purred joyously and seemed very happy to have these new fur babies.

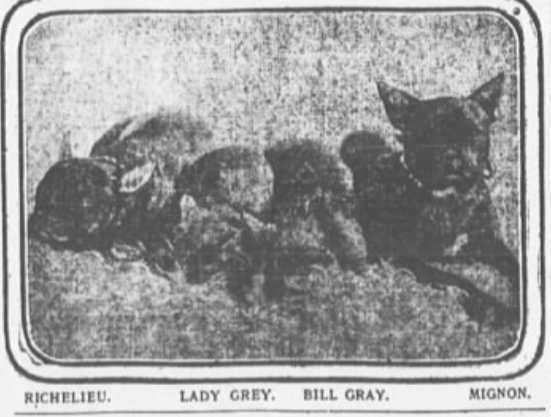

Mrs. Fahnestock named the all-gray felines Lady Gray and Bill Gray. To ensure adequate milk production, she fed the mother cat one pound of ground beef and all the milk she could drink every day.

As the Times noted:

Since then the cat has nursed and cared for the puppies with as much devotion as she shows to her own kitten. The kitten and pups are all thriving and all is peace and harmony in this strange family.”

Mrs. Fahnestock told the press she hoped to begin showing the orphan puppies at the kennel shows in the future. Sure enough, seven months later, two of the dogs–Migon and Richelieu II–won blue ribbons at the Long Island Kennel Club show. Apparently, as the commercial goes, milk does do a body good, even if it’s feline milk and the body of a French bulldog.

Richelieu and Mignon Protect Lady Gray

According to the New York Sun, which ran a follow-up story in April 1905, the puppies took part in numerous exhibitions. They missed their feline mother whenever they were away from her, and they were always happy to find her waiting for them at the front door when they came back home. “The way she purred and rubbed noses with her dog children while they jumped around her yelping with delight showed the affection existing between them.”

Richelieu and Migon were also very protective of Lady Gray. The three often strolled down the street together, and whenever “an ignorant dog” dared to bark at the cat, the two dogs would immediately come to their foster mother’s defense. “More than once she has seen Richelieu bristling all over at an insult offered her through the gate of her home and he has occasionally given an offending dog a good shaking,” the Sun wrote.

Lady Gray adored her extended family–according to The Sun, she seemed to adore the dogs more than her own feline son. The only problem with the arrangement, The Sun noted, was that she never taught her canine kids how to bury bones and dig them up again.

This is the end of Lady Gray’s story. If you also enjoy history, please read on for the history of Malbone Street and the Malbone Street animal shelter, from where Lady Gray and Bill Gray were rescued.

A Brief History of Malbone Street

Malbone Street is named for Ralph Malbone, a descendant of Rhode Island merchants who sold mahogany and, sadly, slaves. Malbone came to Brooklyn in 1809, where he worked as a grocer. He established a homestead and farm on land bounded by Montague, Joralemon, Clinton, Court, and Fulton Streets.

Shortly after his arrival in Brooklyn, Malbone met Jane Schenck, who was the daughter of Nicholas Schenck Jr., a descendant of prosperous landowners and slaveholders of Dutch heritage. Despite her family’s protests, the two lovebirds married in 1815 and had four children. Over the next 20 years, Malbone sold smallpox inoculations, insurance, carriage cushions, paving stones, and groceries (his store was at the junction of Fulton, Pearl, and Willoughby Streets).

During this time, Malbone also made a fortune in real estate—some of his holdings were along the old Clove Road (the main thoroughfare from Bedford Corners to Flatbush and Canarsie), a few blocks east of Prospect Park. In the 1830s, he developed a rustic neighborhood here, which was called Malboneville for many years.

In 1833, Malbone built a large, one-and-a-half-story, five-bedroom house fronting the Clove Road between Crown and Montgomery Streets. The Malbone family lived there until 1837, which is when Ralph and Jane moved to Fayette, in upstate New York.

Jane Malbone lived in Fayette until her death on May 28, 1843, at the age of 51. Ralph moved back to Brooklyn and opened a real estate office at 1 Front Street, where he worked until his death in 1860. Although Ralph had remarried, he was buried alongside Jane at the Dutch Reformed Church Cemetery in Flatlands, Brooklyn.

When the Malbone’s moved to Fayette in 1837, Tom French, an Irish grocer, purchased their home on the Clove Road. He opened a general store, which in later years became known as French’s Tavern.

According to an article published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1888, Mrs. Bridget French sold groceries, dry goods, and liquors at the country store, while Tom French traveled around the country peddling his wares.

French’s subsequently became a roadside tavern for sporting men before and during the Civil War; it also served as a stagecoach inn for the stages running from the Fulton Ferry to Carnarsie and as a halfway house for farmers from Carnarsie, Flatbush, Sheepshead Bay, and Coney Island–it was not uncommon to see 100 farm vehicles in the vicinity on any given day.

In its heyday, crowds would gather at French’s to participate in shooting matches, raffles, cock fights, horse races, and other amusements. But alas, when the old Clove Road ceased to be a thoroughfare in the late 1860s, the hotel shut down and reverted to a private dwelling.

In 1888, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the building was occupied by French’s only surviving daughter, Mrs. Welsh (Tom and Bridget French had 11 children). The outbuildings were also still standing, as was the pump where the horses were once watered. A row of trees indicated what used to be the tavern plaza.

Malbone Street Renamed Empire Boulevard

On November 1, 1918, a speeding Brooklyn Rapid Transit train derailed in the sharply curved tunnel beneath Willink Plaza, at the intersection of Flatbush Avenue, Ocean Avenue, and Malbone Street. Close to 100 people were killed, and about 250 other passengers were injured in what is still the deadliest rail accident in New York City’s history.

The wreck was so horrific, the city renamed Malbone Street (save for a one-block stretch) Empire Boulevard one month later. No one in Brooklyn wanted to live or work on a street associated with so much tragedy. The tunnel where the crash occurred still exists, but it is used only to turn around Franklin Avenue shuttle trains with no passengers aboard.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/f8/82/f8826072-4be8-4e74-914d-ada6189037aa/img_114322.jpg)

A Brief History of the Malbone Street Animal Shelter

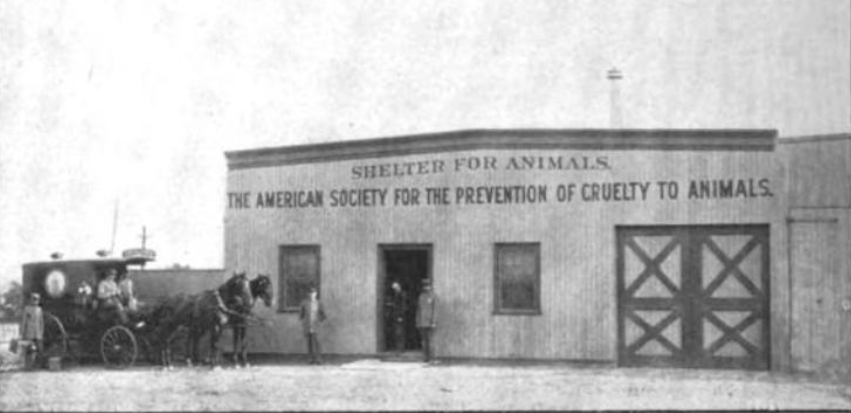

The ASPCA–founded in New York City in 1866–opened its first Brooklyn animal shelter on the corner of Malbone Street and Nostrand Avenue in 1895. That year, the control of stray dogs was transferred from Brooklyn’s mayor to the society, which also had the authority to capture stray cats. The shelter accommodated dogs in apartments on one side the building; the cats had small, tiered kennels on the opposite side of the building.

According to an article in The New York Times about the new shelter, the facility was “clean, convenient, airy, and spacious, although it is only a temporary wooden structure, which, it is hoped, will soon be replaced with a larger, better-constructed building worthy of the city.”

According to the paper, the building had been a car stable for the Brooklyn Heights Railroad Company, when its cars were drawn by horses. The president of the railroad company, Clinton L. Rossiter, and the treasurer, Col, T. T. Williams, joined several other prominent Brooklyn residents in making arrangements for the new shelter.

In 1913, a new animal shelter at 233 Butler Street replaced the outdated facility with a modern, sanitary, fireproof structure in a location more convenient for most Brooklyn residents. The building was greatly expanded in 1922 to accommodate offices and a garage for motorized rescue “ambulances.”

The ASPCA moved out of the Butler Street facility in 1979. The building was purchased by Steve Uhrik and Larry Trupiano, who operated a guitar shop–RetroFret Vintage Guitars–and a pipe organ business. Over the years, other various tenants occupied the former garage space for brief periods of time.

During the mid to late 1980s, people often brought animals to the building, thinking it was still a shelter owned by the ASPCA. Occasionally, the tenants would find animals abandoned by the front door.

In 2017, MacArthur Holdings, a real estate developer, purchased the building for $9.5 million. Most recently, the former shelter was occupied by a hi-fi record bar, sound room, and vegetarian cafe.