I recently wrote about Robert Bruce MacMurray, a horse-saving fire dog of the New York Fire Department. This cat tale of Old New York, about a blacksmith feline who gave the alarm of fire, proves that the cats of Gotham were also heroes.

“Thomas, a big cat, was the hero of a fire that destroyed the upper part of a stable at 426 and 428 East Seventy-fifth Street early yesterday morning.” So begins a story about the cat in The Sun on November 26, 1906.

According to the report, Aloysius (Alois) Dill, a blacksmith, was asleep on the second floor with his wife Anna and two of their three children when Thomas began scratching at his bedroom door. The cat continued to meow until Dill got out of bed to see what was wrong.

Smoke was pouring up from the first floor, where Dill had his blacksmith shop. He quickly aroused his family and got them safely outdoors. Thomas the cat disappeared.

Two alarms were sounded, owing to the size of the fire and the danger to the adjoining tenements. Within a few minutes, the entire upper part of the building was in flames.

When the first fire engine arrived, ten families living in a five-story building at 424 East 75th Street had become panic-stricken. Policemen O’Brien and Walsh of the East 67th Street police station were able to get all the family members to the street without harm.

After about an hour of hard work, the firemen got the blaze under control. They assumed that the 21 horses in the basement stable under the blacksmith shop had all burned to death.

When the men went down into the basement, they found all the horses standing in their stalls, apparently unaware of the flames that had raged overhead. It turns out that the water used to put out the fire had poured into the basement and the animals were knee-deep in water.

On the back of a large gray mare was Thomas the cat, meowing piteously and seemingly giving an alarm that danger was at hand. He had apparently jumped up on the horse to stay dry after saving his human family.

The fire did $20,000 in damages. Captain Nat Shire of the East 67th Street police station was the only one injured: he tripped over a fire hose and wrenched his right knee.

A Brief History of the Henry Bock Building

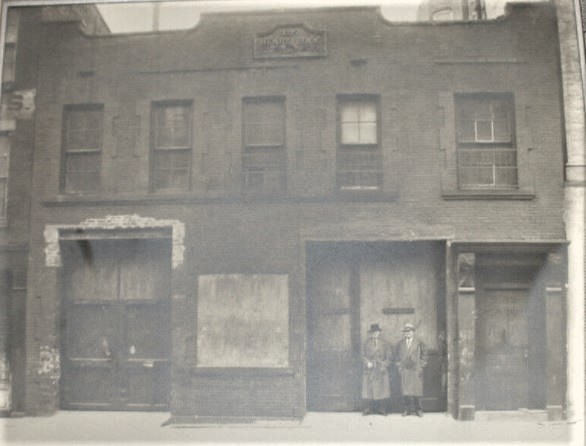

The two-story brick stable, dwelling, and blacksmith shop where this story took place was purchased by Philippine E. Lattemer Bock in October 1895 for $11,000. Philippine and her husband, Henry Carl Bock, lived on the top floor with their children Frederick, Henry, Elfrieda, Dora, and Edward. Henry Bock was a blacksmith who made horse shoes.

Henry Bock and Philippine E. Lattemer were both born in Germany about 1863. They were married on November 7, 1885–about three years after coming to America. The couple was living at 406 East 75th Street when they purchased the home and blacksmith shop.

One month before the fire, in October 1906, the Bock family moved to Seattle, Washington, and the Dill family purchased the property for $17,000. Born in Germany in 1880, Aloysius Dill married Anna Roeder in 1901. Like Bock, Dill was also a blacksmith who made horse shoes.

The Dill family remained in the home until moving to Hempstead, Long Island, sometime between 1925 and 1930.

The Henry Bock building was altered in 1917 and again in 1957. Over the years, the building has been occupied by a lumber company and an auto shop. Today, appropriately, the building houses Country Vets and the American Youth Dance Theater.

The Richard Riker Farm and Arch-Brook Mansion

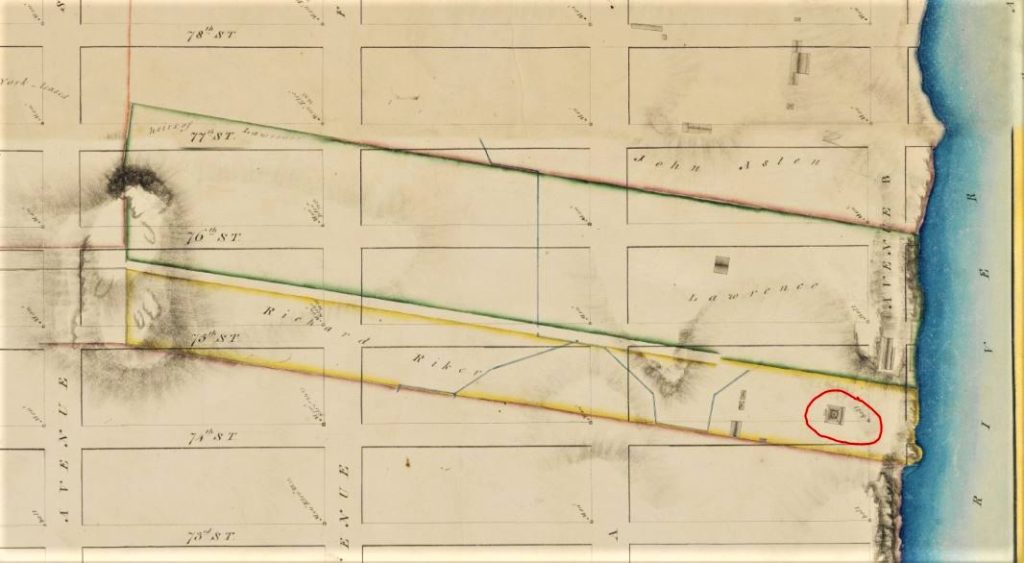

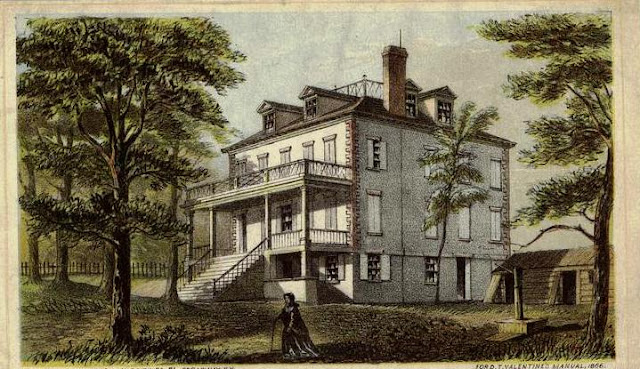

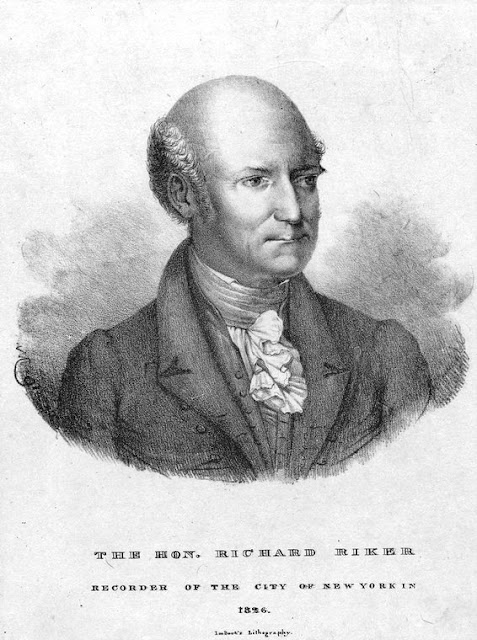

The Henry Bock house was built on what was once the 12-acre farm of Richard Riker, a city recorder for New York. The farm straddled East 75th Street from the East River to about Second Avenue. Riker’s home, Arch-Brook Mansion, was on the East River.

The property goes back to the 1630s, when Dutch settlers used a rushing stream called the Saw Kill to power a saw mill on the East River. In 1677, George Elphinstone and Abraham Shotwell purchased the mill and converted it for leather manufacturing. It then passed on to Sarah Bradley Cox, a widow who married the famous Captain William Kidd.

The Kidds used the mill farmhouse in summers for a few years until Kidd was hanged for piracy and murder in 1700. The land passed through several families until March 6, 1806, when it was sold at $30,000 in foreclosure to three brothers-in-law—Richard Riker, John Lawrence, and John Tom.

Following Tom’s death a year later, Riker and Lawrence divided the large farm in half, with Lawrence renovating the old farmhouse on his section and Riker building a stone, Georgian-style dwelling on his land in 1891.

According to Matilda Pratt Despard, author of “Old New York, From the Battery to Bloomingdale” (1875), “A brook ran through the grounds, and wound its way through the lawn to the river; and after he had built his house, Mr. Riker, in order to make a wide slope of unbroken lawn, threw over this brook an arch of solid masonry.” Reportedly, Riker named his mansion Arch-Brook for the stone arch.

Richard Riker died at Arch-Brook at the age of 69 on October 16, 1842. The Riker family divided the estate into city lots, two upon which the Henry Bock house, blacksmith shop, and stables were constructed. Arch-Brook was preserved for many more years, situated within the city block of 74th and 75th Streets, between Avenues A and B and a stone wall was built to protect it.

During its final years, the home was occupied by the family of John Matthews, a wealthy businessman who made a fortune in the soda water business.

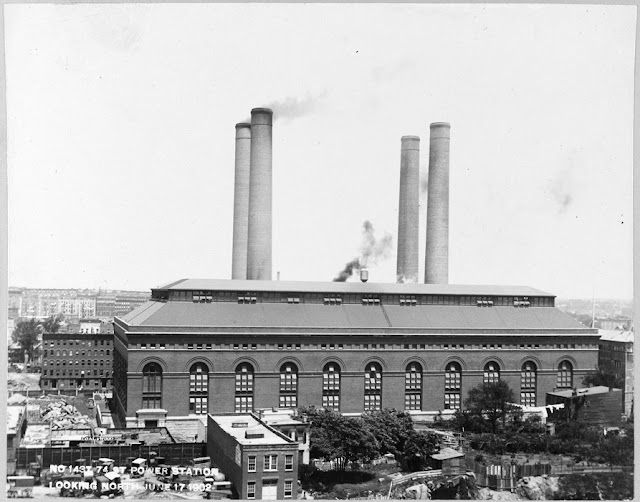

When Elizabeth Matthews died in the late 1890s, the house sat vacant, its high stone wall slowly eroding until there was little left of them. On July 7, 1899, The Sun announced that the building was going to be demolished to make way for a powerhouse for the Manhattan Elevated Railroad Company.

Now owned and operated by Con Edison, the powerhouse was completed in 1903.