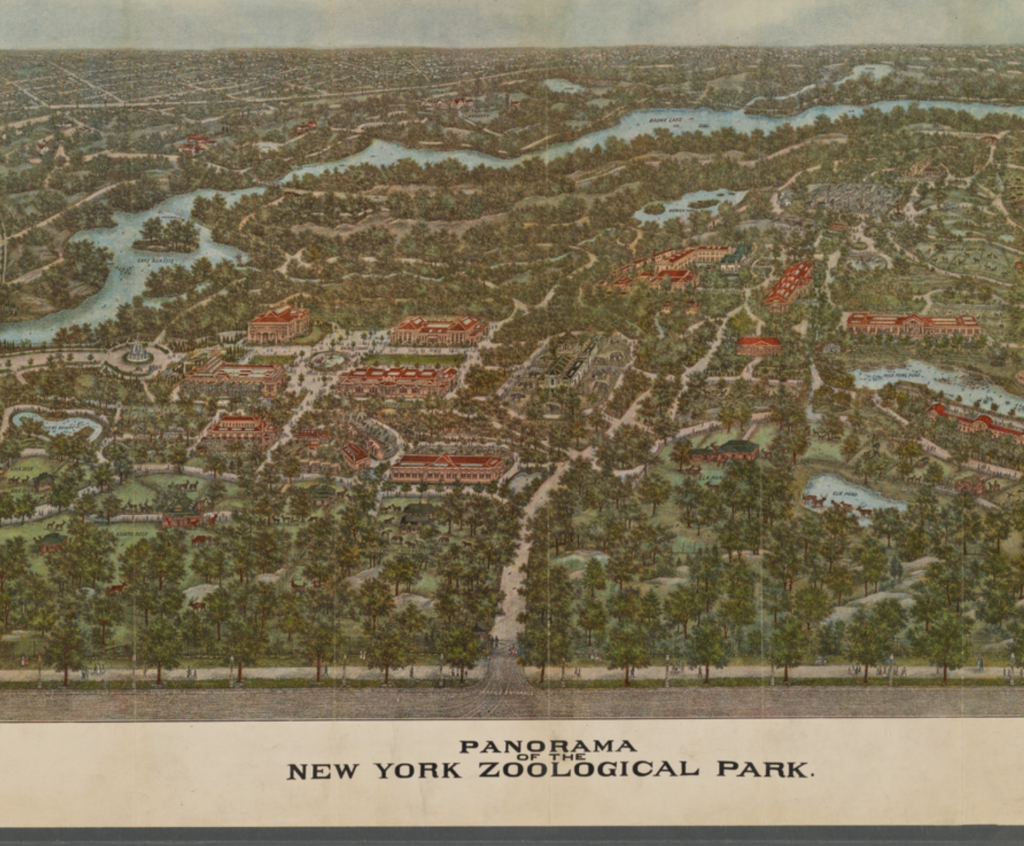

During a recent virtual presentation, someone in the audience asked me how I discover the animal tales that I share on my website. I explained that I often stumble upon new stories by accident while doing research for another story. I was working on a story about Oliver Herford’s cat when I discovered this tale about a panther hunt at the Bronx Zoological Park (today’s Bronx Zoo) in 1902.

As I read the news article, which was published on July 29, 1902, I realized that this report was about Day 2 of the great panther hunt. In other words, I had stumbled upon the middle of the story.

So, I still had to do some research to find the beginning and the end of the panther hunt story. My husband will attest to my loud burst of laughter when I discovered how this panther story ended. It has something to do with a pool table. Stay with me; I think you’ll enjoy the tale.

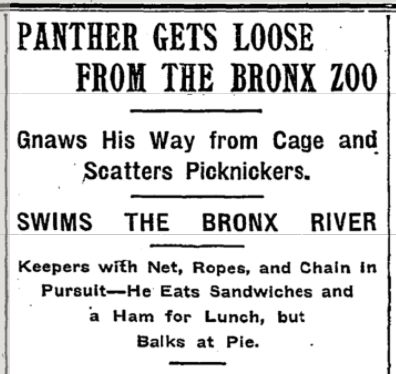

The Beginning of the Great Panther Hunt

On July 28, 1902, The New York Times reported that a seven-month-old, 45-pound, grey-brown panther had gnawed his way out of a large pine shipping box near the park’s Puma and Lynx House. It was the first time the captive cat–which had just been shipped via a Ward Line steamship from Mr. Charles Sheldon of the Mexican Zoological Society in Chihuahua to Director William Temple Hornaday of the New York Zoological Society–had ever experienced a taste of freedom.

One of the first things the cat did upon his escape was make his way toward a group of women and children who were having an early picnic lunch in the grass near the wild fowl pond. As they began running away, the panther leaped over their heads and landed about 20 feet from the ground in a chestnut tree. He then leapt to another tree deeper in the foliage, where he disappeared from sight.

Within minutes, everyone in the park had heard about the panther’s escape. News also spread to the adjoining Botanical Gardens, where about 2,000 people had gathered that day to hear an outdoor concert.

Zoo keepers, who were secretly alarmed by the panther’s escape, gathered up ropes, collars, and chains and set out to hunt for the young cat. Director Hornaday and curator Raymond Lee Ditmars gave orders for the zookeepers and the 10 men of the Bronx Park Police to capture the cat alive, and to inform all the patrons that the young cat was friendly and harmless.

Naturally, very few people in the two parks that day believed that the panther was harmless. Many families left their picnic blankets and baskets of food and ran for the closest shelter. According to the Times, the panther took advantage of this situation, devouring numerous sandwiches, an entire baked ham, and half a pie (he didn’t the pie too much).

The zookeepers were no match for the panther. Just as they closed in on him, he would leap into a tree or sprint through the woods. At one point, a group of men on the east side of the Bronx River watched as the cat jumped into the river and swam with “fine, vigorous strokes” to the east shore.

After hours of searching with no capture in sight, the men called off their hunt for the evening. Director Hornaday theorized that the panther would either be shot or would escape to areas further north where there were fewer people. Curator Ditmars told the press he was greatly concerned that the lost panther would only be fit to make a rug when it was captured.

The Middle of the Great Panther Hunt

On the day after the young cat escaped, the New-York Tribune reported that the great panther hunt was continuing “merrily” in and around the park.

Motorists raced up up and down the parkways while peering into bushes for the lost cat; bicycle and mounted policemen from three nearby police precincts patrolled the roadways hoping for something more exciting than the standard runaway horse; small boys with their dogs waited in the woods off Unionport and Boston Roads with air guns, slings, and bows and arrows; and timid women sweltered behind closed doorways in fear of every noise that resembled a growl in any way.

At one point, Director Hornaday requested the police to stop looking for the panther, and instead turn their attentions to the bands of young boys hiding in the woods. As the Evening World noted, “the opportunity to hunt a real, live, man-eating beast in the jungles of the Bronx may not occur again in their lifetime, and the youth of the Annexed District are not overlooking it.” Hornaday did not want any harm to come to the panther.

The panther was reportedly last spotted the following morning at 146th Street and Southern Boulevard. Several young boys told Mounted Policeman David Fanning they had seen the young cat in the bushes. A team of zoo keepers and two coon dogs were dispatched to the site.

It was hoped that the dogs could track down the panther and tree the small panther. Then the zoo keepers could work with their nets to lure the panther down.

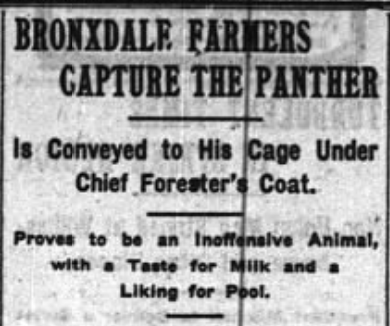

The End of the Great Panther Hunt

On Wednesday, July 30, the New York newspapers reported that the residents of the Bronx were able to breathe a little easier. Little children were once again able to play outdoors. The “ferocious” panther that had escaped from the Bronx Zoological Park had been captured and returned to his cage after three days on the lam.

According to The New York Times and Yonkers Herald, a farmer named John Spears discovered the panther in his stable yard on the Boston Road between Bronxville and Eastchester.

Spears was carrying a bucket of oats and had just passed his chicken yard when he noticed two green balls glaring at him through the dusk, from inside the chicken house. He threw the pail of oats at the animal and cried for help. Then he locked himself in his barn and waited for his wife and son to come to his rescue.

Carrying various weapons including a shotgun, Spears’ wife and son approached the barn. A nearby panther hunting party led by Clark Joslin also came to Spears’ aid. By that time, though, the panther had already run to the other side of the fields.

Using pitchforks, rakes, shovels, and sticks, the men beat through the tall grass approached the panther. At one point the cat attempted to charge his pursuers, sending most of the men in all directions. Spears, his son, and Joslin held their ground.

As the panther continued walking toward the men, Joslin called out, “Here, kitty, kitty” in a soothing voice. He was able to slip his belt around the cat’s neck while the other men placed a fishnet over the panther.

Now, here’s where the ending of the story gets a bit fuzzy. I’ll tell both accounts and let you decide which one is better.

According to the Yonkers Herald, after the men had captured the panther they telephone Director Hornaday. He instructed them to notify Herman W. Merkle, the park’s chief forester, who lived nearby in Bronxdale. Then the men carried their captive to the Bronx Park police station in the old Lorillard mansion, where they waited for Merkle to claim the panther and return him to the zoo.

The New York Times tells a very different story. According to this newspaper, the men carried the captured cat to a placed called Reisen’s roadhouse, where they removed his net and fed him a large bowl of fresh milk.

Noticing that the panther appeared to be playful, the men carried him upstairs, where there was an unused pool table. They placed him on the table and watched in delight as the small panther chased the balls into the side pockets.

Soon, playtime for the panther was over. Chief forester Merkle appeared at the roadhouse and returned the runaway cat to his new home at the Bronx Zoological Park. I have a feeling the panther had some amazing dreams for the rest of his life.

If you enjoyed this story, or you want to explore the history of the Bronx Zoological Park, check out my story about the iguanas that escaped from the park in 1908.