Dolph the cat could do many tricks, but his skills did not come in handy when he got stuck in the Ice Palace Skating Rink on East 107th Street.

Dolph was the pet of Wolf Falk, an East Harlem resident who worked as the manager for comic opera comedian Thomas Q. Seabrooke. Dolph (perhaps named for John Henry Dolph, the famous cat painter of that time period?) was reportedly not as clever as Snooperkatz, the silk shop mascot cat who stole postage stamps from his master’s desk to exchange them for milk from the milkman. However, he was quite skillful at walking on his hind legs, jumping through hoops, and doing other tricks that ordinary cats could not do.

In his prime, Dolph was described as a “nice, plump sleek animal” who pretty much kept to himself. He never associated with any other neighborhood cats, albeit, he was friendly with a Harlem goat. It was this goat that got Dolph into some serious trouble.

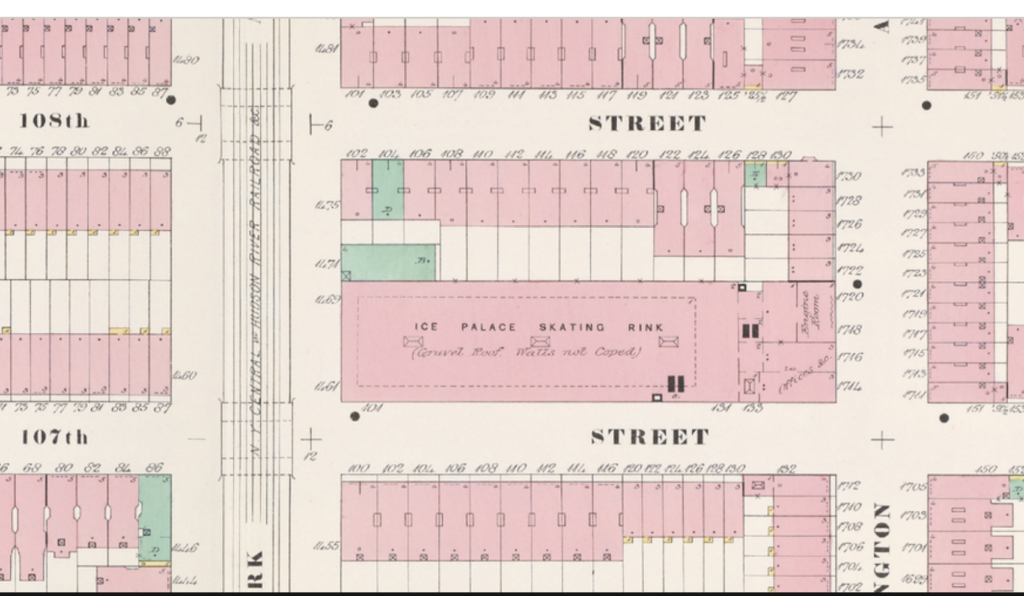

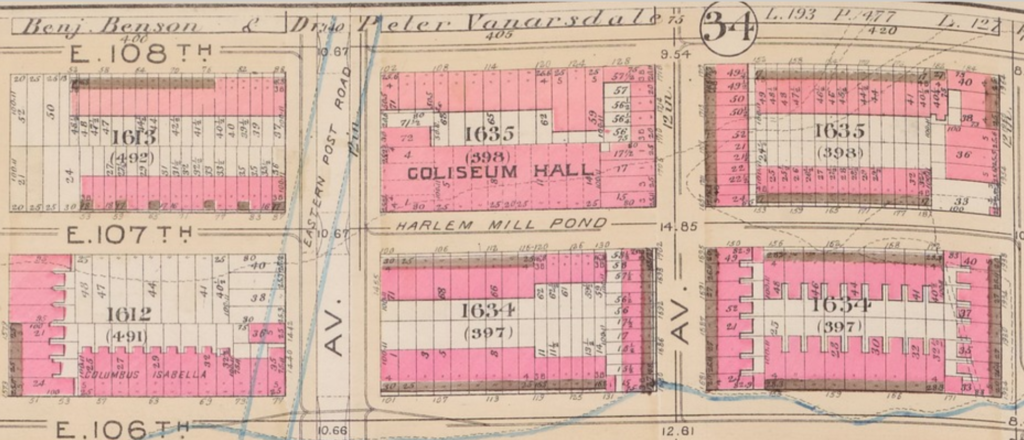

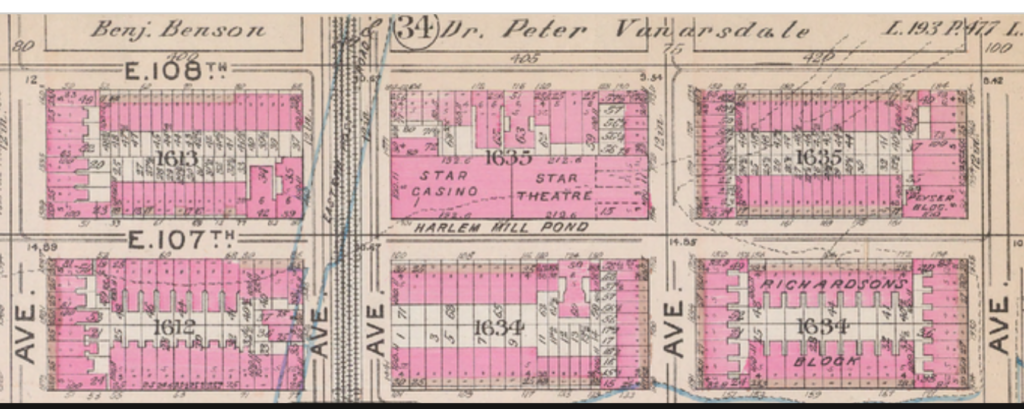

According to the tall tale, as reported in The Sun, the trouble centered around the Ice Palace Skating Rink, which was constructed in 1895 in the old Coliseum Hall and armory building on 107th Street between Lexington and Park Avenues.

After construction had been completed, truckloads of brilliant papier mache icicles for interior decoration began to arrive. The icicles were to form a sort of sub-ceiling, and plans called for a space of just under two feet between the two ceilings. (Can you start to see where this is going?)

The goat, who had been living on tomato cans, nails, and broken glass for months, could not resist the smell of papier mache. Following his nose, he ran to the new Ice Palace Skating Rink, only to find that the ice ceiling was almost complete and out of his reach.

As The Sun noted, “He stamped about for an hour, keeping his eye all the while on one particularly appetizing icicle that looked so much like the real thing that the thought that it might ultimately melt and fall off was pardonable even in so wise a goat.”

The goat ran down Lexington Avenue and stopped in front of Mr. Falk’s house, where he bleated a special signal to summon his feline friend. Dolph saw his goat friend through the window and exited the basement door to join him. “There was consultation and then off the two started, and a few moments later halted in front of the ice palace.”

The goat gave Dolph a few instructions, and the cat took off, scrambling up the felt-covered walls toward the ceiling. He then dodged into a hole that marked the uncompleted part of the sub-ceiling. According to The Sun reporter–who noted that details of the story were not all necessarily true–Dolph bit off a few icicles for his goat friend.

After satisfying his friend’s hunger, Dolph decided to satisfy his curiosity by prowling around between the two ceilings. Meanwhile, workmen continued building the icicle sub-ceiling, eventually sealing the hole through which Dolph had entered.

Like Dan, the fire cat that got stuck between two ceilings in his firehouse only a year earlier, Dolph was stuck for good.

A few days later, a watchman happened to look up at the ceiling. He noticed that it seemed to be swaying up and down in a wavy motion. He rubbed his eyes and looked again. Yes, the ceiling appeared to be moving.

The watchman reported the moving ceiling to the workmen, but they just laughed at him and attributed the movement to the wind. The watchman continued to watch the ceiling every night, and every night it continued to move.

Then one night he heard a large commotion followed by a scratching noise. When he told the workers about it the next day, they agreed to remove a portion of the ceiling. A few seconds later, a little cat face appeared at the edge of the hole and made a faint “meow.” The workers reached in, grabbed the cat, and carried him down the ladder.

After spending eight days trapped in the ceiling without food and water, Dolph was no longer recognizable. Like Kelly, the poor kitty who was trapped in a mail sack for eight days, Dolph had lost a lot of weight and was weak with hunger.

The news of the rescue spread about the neighborhood, and many children came to visit the cat to bring him food. As for the goat, Mr. Falk told the reporter that Dolph and the goat were no longer friends. Apparently, the two met up on Lexington Avenue, but while the goat bowed, “Dolph cut him dead.”

A Brief History of the Ice Palace Skating Rink

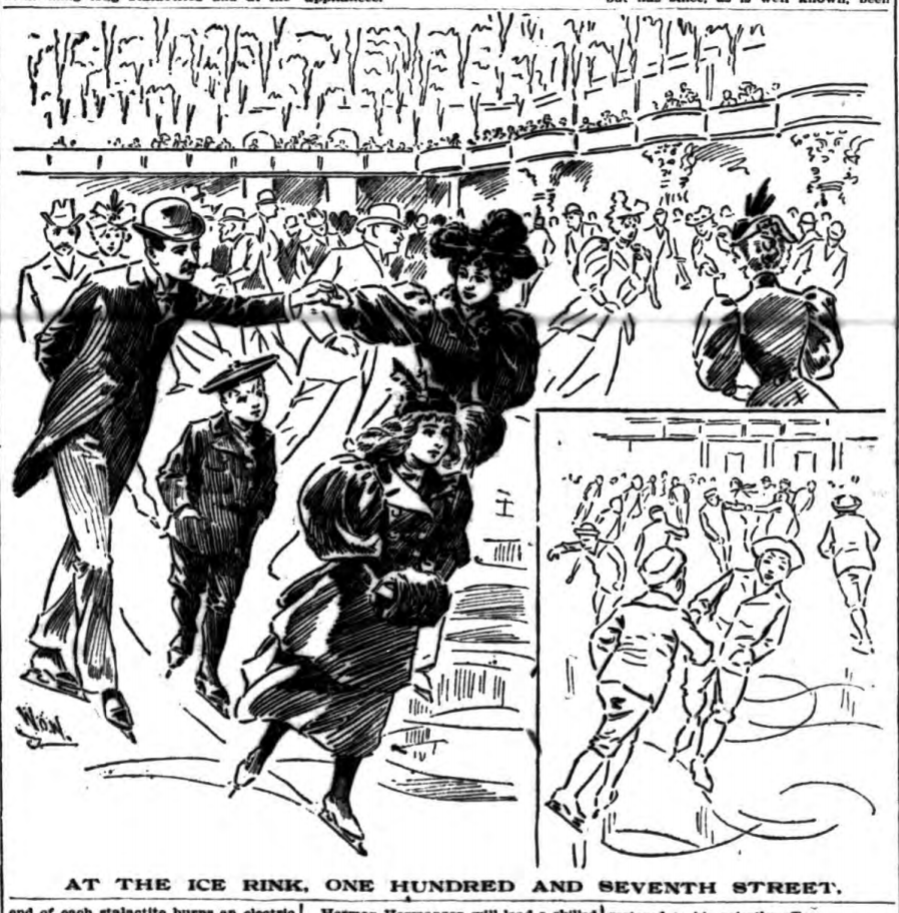

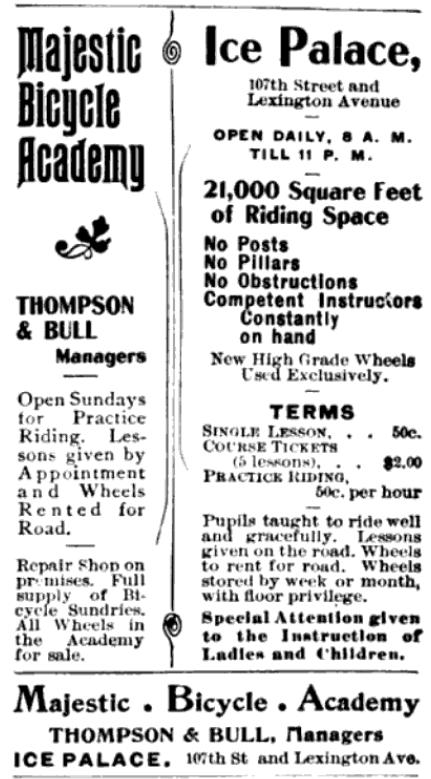

The Ice Palace Skating Rink on the northwest corner of Lexington Avenue and 107th Street opened in December 1895. With a large ice surface of 20,000 square feet (265 long by 71 feet wide), it was then the largest indoor ice skating rink in the world.

The smooth ice surface was five inches thick and comprised about half an acre of dry ice with temperatures of 40 degrees on the rink and about 70 degrees around the galleries and in the lobby. There were 15 miles of one-inch pipe beneath the surface into which immense ice machines pumped a brine mixture.

The rink could accommodate about 2,000 skaters at a time. The building also featured a café, restaurant, cloakroom, and six club rooms, which were occupied by members of the Ice Palace Skating Club, Knickerbocker Skating Club, Ice Palace Polo Club, and the New York Hockey Club of the American Amateur Hockey League. All sorts of ice-related athletic events took place there, including hockey, figure skating, ice lacrosse, and ice polo.

According to The New York Times, the arena was “one of the most entrancing sights in Gotham.” All the walls above the gallery and the roof were decorated in icicles and stalactites “and frost everywhere so natural as to be very deceptive—while studded around in all sorts of obscure places are brilliant electric lights.” As the Times noted, “Jack Frost has been completely knocked out by the Ice Palace Skating Rink.”

The Ice Palace was constructed within the walls of an older building called Coliseum Hall, or the Coliseum building. Constructed in 1885 on land that had once been under the Harlem Creek, the Coliseum also served as a skating rink, albeit, for roller skating. The stone and brick building was 440 x 130 feet, and said to be the largest rink in the world at that time.

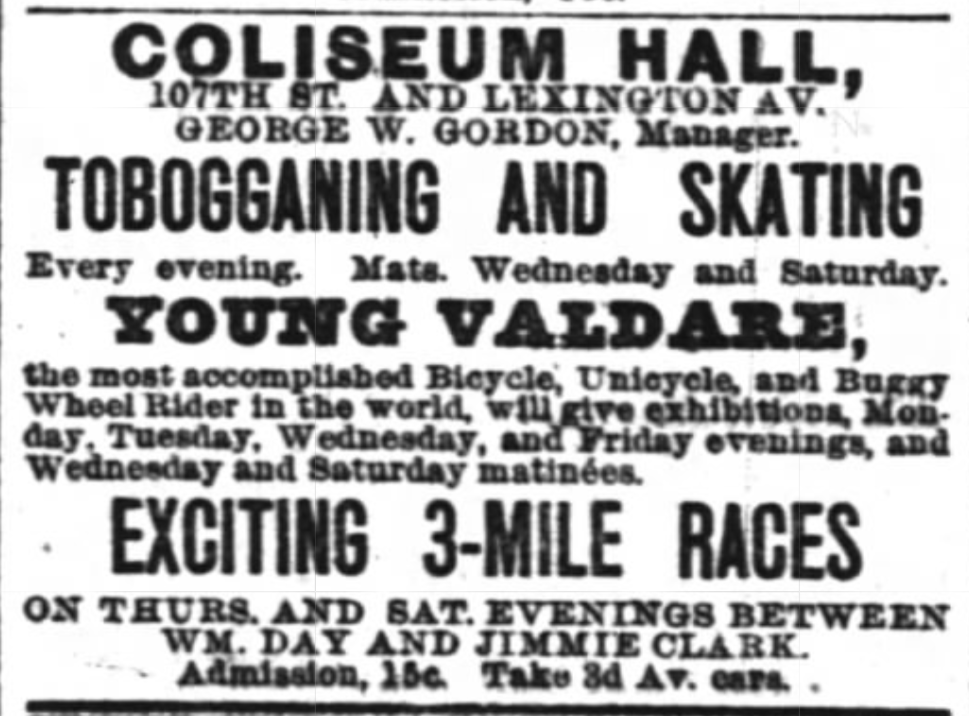

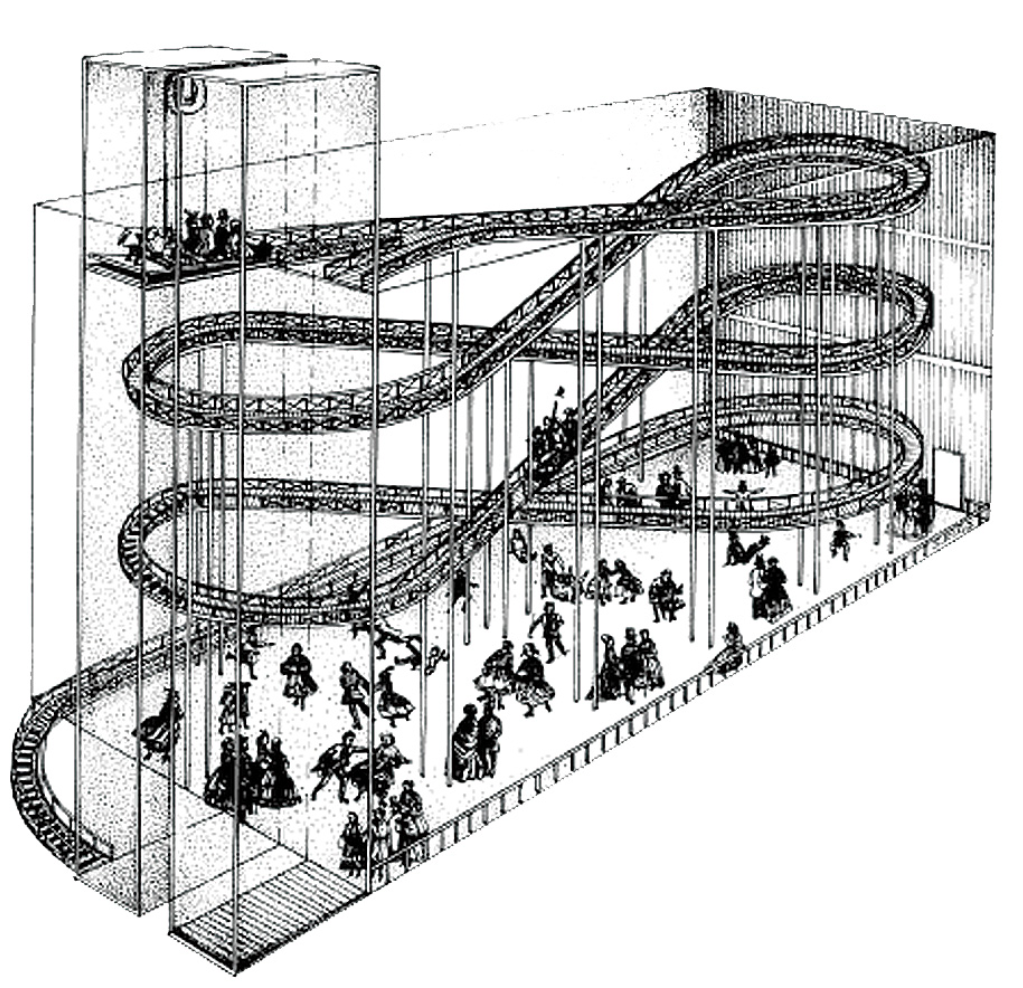

Coliseum Hall featured some unusual events, including skating races, bicycle exhibitions, and a tobogganing slide (which looked like something you’d see on a large, modern-day cruise ship).

The Ice Palace had a very short life as a dedicated ice-skating rink.

Within a year, the arena was also home to the Majestic Bicycle Academy owned by David I Thompson. Tom O’Rourke’s Lenox Athletic Club also used the facility for boxing events.

And by September 1897, the Ice Palace was reportedly operating as a music hall, featuring low admissions to a variety of burlesque shows.

From 1898 to 1899, the old Ice Palace served as an armory for the 71st Regiment, and later, the 8th Regiment, of the National Guard. Then in 1901, an architect named Samuel Cohen filed plans to reconstruct the old Ice Palace as a traditional theater.

By 1904, the building had been converted into two facilities: The Star Theatre, a vaudeville/movie house that used the old Ice Palace entrance on Lexington Avenue, and the Star Casino, which fronted 107th Street and was operated as a ballroom and sports arena.

Don’t Cry “Fire!” in a Theater

In 1908, the Star Theatre was leased to William Fox, who was then just starting to purchase a chain of theatres throughout the city (his legacy continues to live on in the form of the Twentieth Century-Fox Studios). At this time, the Star Theatre could accommodate 2,300 patrons.

In January 1909, a small child wandered away from her mother during a movie at the Star Theatre. About 2,000 people were in attendance that day. Unable to find her child, the woman shouted “Fire!”

Soon, others began shouting that there was a fire even though they didn’t see or smell smoke or flames. Everyone in the theater began making a mad rush for the exit doors in the dark.

Two policemen tried to stop the frightened crowd–they even turned on the theater lights and announced that there was no fire–but by that time it was too late. Several patrons ran to the alarm box and called for the fire department. The New York Times did not report on any charges filed against the woman.

The End of the Star Casino and Theatre

Sometime around 1938, the Star Casino was converted back to the building’s original use: an indoor roller-skating rink (without the toboggan slide).

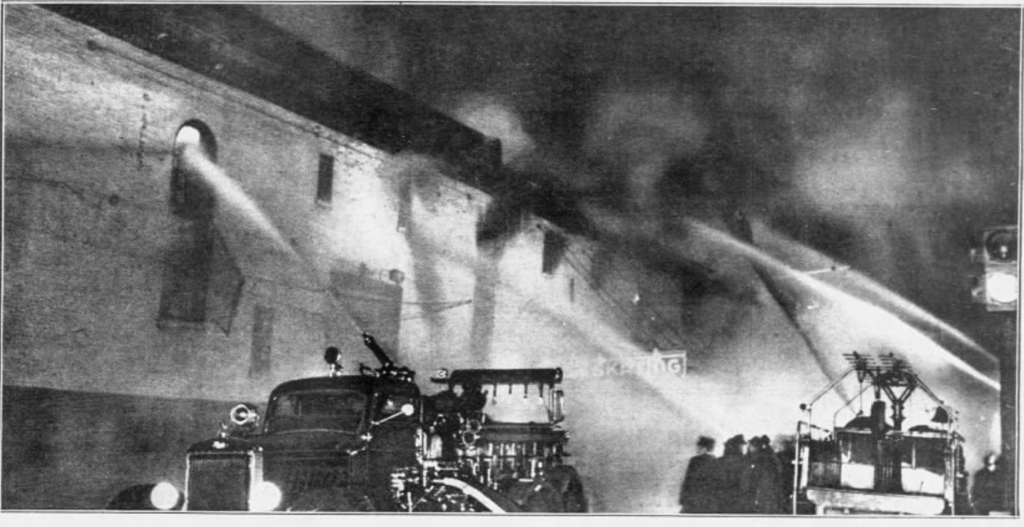

On March 14, 1939, a five-alarm fire destroyed the old Star Casino. The last skater had left the rink less than an hour before the blaze was discovered at midnight, but about 1,000 patrons were still watching the last few minutes of a movie in the adjacent Star Theater.

According to The New York Times, when smoke drifted into the auditorium, assistant manager Frank Garcia calmly asked the patrons to leave the theater. They did so without disorder. The fire was believed to have started by a tossed cigarette from one of the skaters.

In later years, a gasoline filling station occupied a portion of this site from 1955 to 1969. For many years, there was only an empty lot on this site until 1985, when the Lexington Gardens residential complex was constructed.