The late 1800s and early 1900s were like a Tale of Two Cities for the dogs of New York City. For stray mutts and other unwanted dogs, there were dog catchers, mean little boys with stones, and a law that required all unclaimed dogs be drowned in the East River. For pampered pooches and high-society dogs, like the spoiled French bulldogs of Princess Amy Isabella Crocker, there were daily massages, jeweled collars, and a brand new dog bathhouse on East 125th Street in Harlem.

When James A. Hogg, a professional rat catcher by trade, opened his new dog bathhouse in Harlem in 1903, it attracted much attention from the press. Sure, there were by this time several hospitals for dogs and other animals. And boarding houses for those wealthy pet owners who could afford it had also been around for years.

But a bathhouse for dogs was quite a novel idea (albeit, there were several “dog nurseries” across the country, where wealthy women could drop off their lap dogs for a day of grooming while they went shopping or attended to other frivolous activities).

As a reporter for the New-York Tribune noted:

If there is any facility for health, happiness and peace of mind which the dogs of New York need and have not got, the man who discovers it should provide it. He will be well rewarded liberally, for dogs are a luxury, and have masters and mistresses who can pay the price.

At the dog bathhouse, every dog had his day as well as his own towel. To ensure that they received the full bathing experience (i.e, didn’t try to run away from the tub), they also had personal attendants to take care of them during their entire visit to the bath.

I don’t know how much James Hogg really knew about dogs, but he certainly knew his clients. As he told the press:

“An aristocratic dog should be bathed at least once every seven days. This is particularly true of long-haired dogs. Nor is ordinary soap and water enough. The water should be highly antiseptic, and if the dog belongs to a woman a perfumery spray is necessary.”

The dog bathhouse occupied one back room on the ground floor a four-story brick building at 63 East 125th Street. A storefront drug store occupied the front of the building. According to census reports and an ad placed in 1903, this was also James’ residence, where he lived with his wife Mary and their five children.

In one corner of the back room was a gas water. There were also two side-by-side tubs in the room–one for large dogs and one for smaller pups. On the walls were towels and muzzles for those dogs who misbehaved during bath time.

According to an ad that James placed in 1903, he charged $1 for short-haired dogs and $2 for long-haired dogs. The services also included nail clipping.

On the day the reporter from the Tribune visited the bathhouse, there was a first-time customer that was not overly pleased to be there. Apparently the cocker spaniel tried to bite the bath attendant as soon as the man tried to put him in the tub. The attendant was forced to place a leather muzzle over the dog while his mistress cried for the man to do whatever it took to bathe her dog.

“Please give him a bath,” she begged “I’ll pay $1 extra.” The attendants threw some bath water on the feisty dog before finally giving up.

The next customer was a large St. Bernard. His mistress assured the men that her dog would not bite and did not need a muzzle.

This dog was much more cooperative, allowing the men to scrub him with a black tar-like substance while standing in the lukewarm water. Following the bath, the men toweled him dry and gave him a thorough brushing. His owner made arrangements for her dog to get a bath every week. One of the young attendants said he would pick up the dog and deliver him back home after every bath.

“The dog bathhouse idea, though new, is taking well among uptown dog fanciers,” the reporter stated. “The dog’s weekly bath, when conducted at home, becomes a formidable affair. Many a household has lost servant after servant for no reason in the world but the dog’s weekly bath. It may be going a little far for every dog to have his own set of towels, but dogs in a city are a luxury, and accordingly should have luxury.”

I could not find out how long the dog bathhouse remained opened. I do know that in 1907, the Plaza Hotel began a doggie day care service for ladies who wanted to leave their dogs in good hands while they had afternoon tea. So perhaps James returned to his original career as a champion rat catcher and left the dog grooming to newer establishments.

James Hogg, Expert Rat Catcher

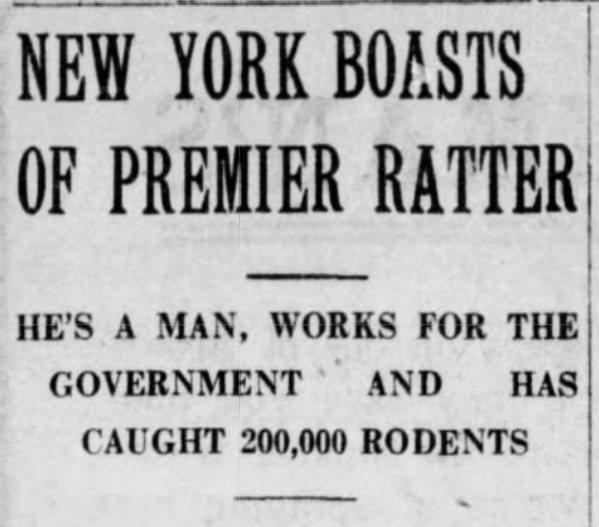

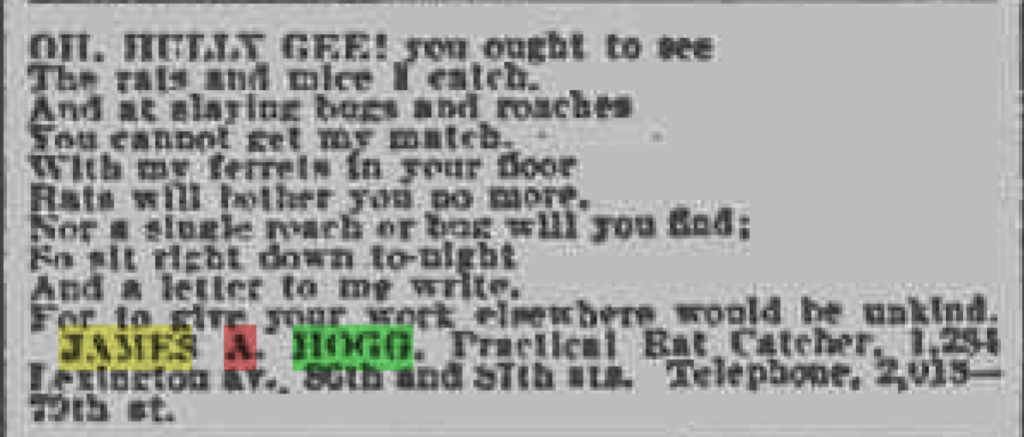

In addition to the bathhouse, James specialized in buying and selling dogs, especially terriers. He was also an expert exterminator, aka, rat catcher. One newspaper called him the “champion ‘Pied Piper’ of the world,” noting he caught 10,000 rats a year.

According to news reports, James took orders to clear rats from ships, factories, hotels, and residences. He was also an official rat catcher with the federal government, in charge of keeping the Federal Office Building in New York City free of vermin since 1894.

(Luckily he wasn’t in charge of the U.S. Post Office Building, or else the hundreds of cats on the feline police squad would have been out of jobs!)

James used a very unusual way to catch the rats. He reportedly set some ferrets loose in the rat holes, and then he’d pluck the rats up with large pinchers as they ran out of the holes to escape the ferrets. He’d then place the live rats in a gunny sack that hung suspended from the floor (if he placed the bag on the floor or counter, the rats would have immediately gnawed their way out).

James donated the healthy live rats to laboratories for experiments, and fed the crippled rats to his ferrets. (According to one news article, he would carry the rat-filled sacks on the subway with him!)

In addition to the ferret method, James also devised a type of electric griddle upon which he placed dead fish to attract the rats, which he would then electrocute. James admitted he didn’t want anyone else to know about his invention until he died, because he depended on the rat population to continue thriving in order to make a living.

James got himself into some hot water in 1913, when he reportedly tried to “get even” with Maxlow Realty Company, owners of the Clearmont Court Apartments at 549 and 551 West 113th Street. According to the janitor, Peter Weck, the Weck family cat alerted him to an army of rats in the basement. When Weck opened the door, the cat ran out, never to be seen again. Weck tried to fight off the rats himself, but he was overrun.

Weck notified Magistrate House of the Harlem Court, who agreed that James Hogg was responsible for liberating the rats. He sentenced James–then described as a small man with whiskers and gray hair–to $500 for good behavior for a month.

By the 1920s, James had taken his business to the Jersey Shore area (where he called himself The Bugman), allowing his son Robert to take over the New York City business. One of the last ads he ran was in 1944, when he was doing business as a termite/exterminator in Asbury Park, New Jersey. By that time, he would have been 73 years old.