Thirty years after the Brooklyn Heights Promenade was completed in 1951, when it was at last basking in popularity, several people came forward to receive bragging rights for designing the public walkway.

A few human engineers took individual credit for conceiving the promenade, while others said it was a team effort. No one brought up the fact that it was a pampered pet cat that first got the ball rolling for the clever and successful concept. Yes, a cat.

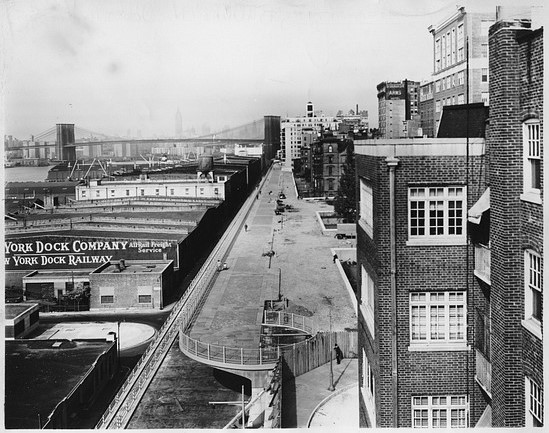

On March 19, 1928, residents of what was then called the Heights gathered at the first meeting of the 1st A.D. Republican Club. The purpose of the meeting was to protest against the New York Dock Company’s plans to erect a 10- or 16-story building at the foot of Joralemon Street. The residents feared that this new building, as well as plans to make other waterfront improvements, would put Brooklyn Heights behind a wall of buildings and obstruct their beautiful view.

In attendance were Paul Windels of 10 Pineapple Street, Amy Wren and Henry Ralston–the co-leaders of the 1st A.D. Republican Club–and several other Heights residents.

The concerned residents noted that restrictions on the height of buildings between the street ends of Orange and Remsen Streets had been in place ever since the old Pierrepont Farm was sold. However, the remaining waterfront property owned by the dock company was at the company’s disposal to do as it pleased, including building skyscrapers. Furthermore, some residents had heard rumors that the dock company was trying to remove the restrictions that dated to the Pierrepont Farm.

In addition to protesting the building plans, the residents also proposed constructing a promenade for children to play on, along the line of warehouses between Furman Street and the waterfront. The group established a committee to investigate this idea.

So where does the cat come in?

It was Amy Wren who put the cat into play.

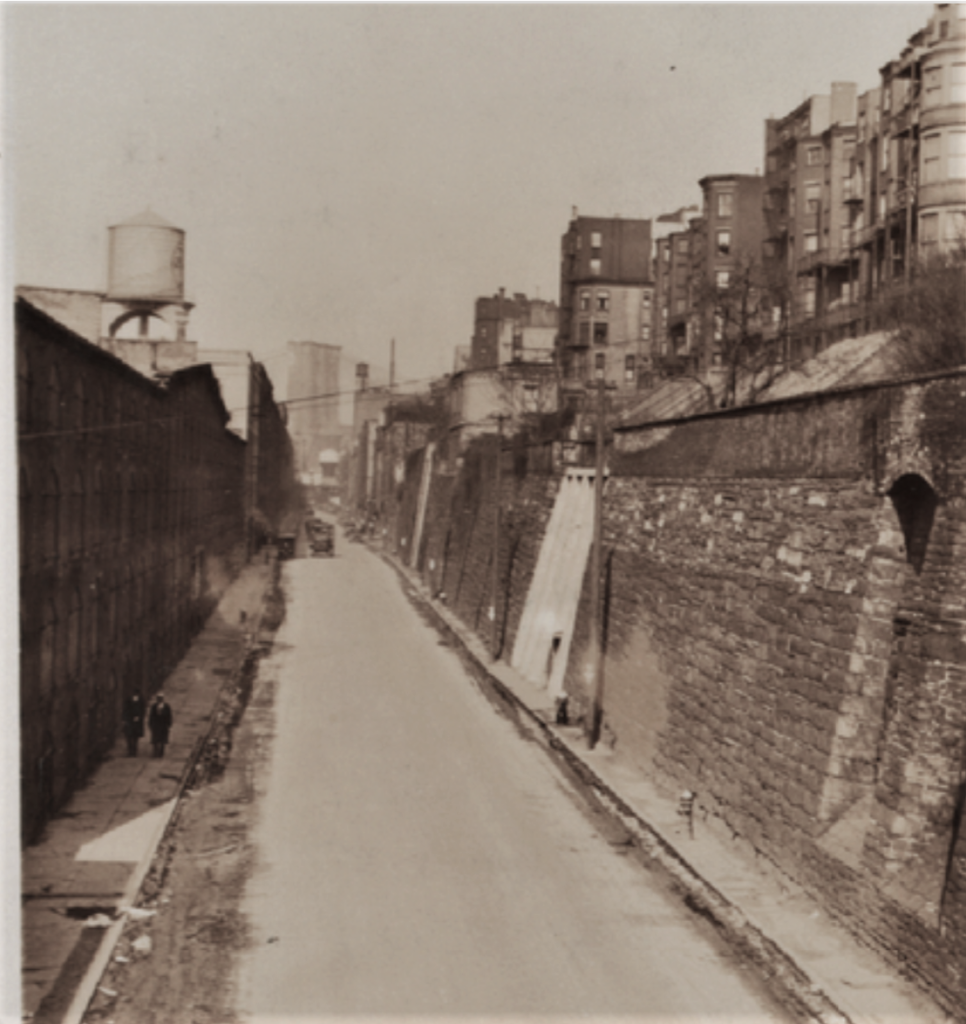

According to Ms. Wren, the present system of shutting off all the mini parks and gardens at the ends of the various streets was a detriment to the community. The fences prevented children and other members of the public from having safe spaces to play and enjoy the waterfront. The only park area opened at this time was the one at the foot of Montague Street.

“A cat was the cause, I believe, for the closing of the other parks,” Ms. Wren said.

“I’m told that some lady wanted to have her own pedigreed cat given the exclusive right to promenade in one of them and so persuaded the city authorities to build a fence around to keep out the other cats of the common variety. I don’t know why we have these little places all fenced around so nobody can get in but cats.”

Mr. Windels took the ball and ran with it, suggesting that a pedestrian promenade along the tops of the factory buildings could provide a play area for children as well as an alternative to the fenced-in private parks and gardens that were currently only accessible by cats and their well-to-do owners.

“Many people are afraid to have their children play in the streets,” he said. “Such a place, with a high fence on each side, would make an excellent playground. Tennis courts might even be built there.”

Mr. Windels surmised that a walkway would not be all that expensive, as they would only need to acquire the overhead easements.

The suggestion to build a promenade atop the old factory buildings was apparently well received and considered. By 1931, the Regional Plan Association was advocating for the construction of parks on top of the buildings as well as a marginal railroad along Furman Street topped by an overhead traffic road.

Of course, the social and political history behind the Brooklyn Heights Promenade is much more complicated than this cat story. But years of discussions and planning and disagreements culminated in 1943, at a hearing before the City Planning Commission.

At this hearing, a proposal was presented for two roadways of three lanes each in either direction to be built side-by-side on top of the Heights escarpment. A deck above the cantilevered highway would serve not for private gardens and privileged cats but as a public esplanade for everyone to enjoy, including humans and cats (and dogs) of all classes.

Demolition of the inland warehouses on Furman Street began in the fall of 1946, followed by construction of the new roadway and esplanade. The southern half of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade opened to the public on October 7, 1950, and a year later, the northern half opened.

The Pierrepont Farm

The principal developer of Brooklyn Heights was Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, whose recorded family history dates to Sir Hugh, Lord of the Castle of Pierrepont, in Picaardy, France (A.D. 980). Hezekiah was born in New Haven, Connecticut on November 3, 1768. At the age of 22, he settled in New York City, where he worked as a clerk at the Customs House.

Following his marriage to Anna Marie Constable in 1802 (Anna was a descendent of Cornelius Dirckson Hoaglandt, the first ferry master in Brooklyn), Hezekiah moved to what was then called Clover Hill in Brooklyn. There, he purchased the old Benson farm, including the Four Chimneys mansion (also called the Cornell mansion), and what remained of Philip Livingston’s distillery at the foot of Joralemon Street.

He added a wing to the old frame mansion and a windmill to the distillery, and he constructed a footbridge to span the ditch that ran down through his property to the waterfront.

The mansion, which stood near present-day Pierrepont Place and Montague Street, was surrounded by lush gardens and orchards, and was a popular destination for courting couples. Many people during this time reportedly dug holes among the hills of the Heights in search of Captain Kidd’s treasure–some folks dug holes on the Pierrepont property, thinking they’d strike gold.

Four Chimneys also had great historical value. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington maintained his headquarters here during the Battle of Long Island. According to news reports, a signal station was set up on the roof to allow for communications with New York. Washington sent orders to his troops from this rooftop station.

The home, surrounded by the estates of the Ludlows, Middaghs, Hunts, Warings, and other prominent Brooklyn families, was also where the first draft of the act incorporating the Village of Brooklyn took place on January 9, 1816.

Hezekiah was a strong supporter of development, and he focused his own real estate investments in the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood. He purchased most of the area between Joralemon Street and Love Lane, and from Fulton Street to the river (all this land had formerly been owned by the Remsen, Livingston, and De Bevoise families).

Incidentally, Hezekiah had also envisioned a promenade from Fulton Ferry to Joralemon Street. According to an article about the Pierrepont family published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in June 1901, the public space that he envisioned would feature trees, flowers, benches, and playgrounds for the children, and the ground would have sloped down to the waterfront, where the public could bathe on a clean gravel beach.

Using his position as a village trustee, Pierrepont offered the village free land for such a promenade. Some reports say he withdrew the offer when one of his neighbors, Judge Peter W. Radcliffe, objected to the proposal. Other reports claim that multiple property owners fought this idea, fearing they would be assessed too heavily for these improvements.

When the promenade proposal met a dead end, Hezekiah proposed another idea whereby a series of “magnificent stone wharves and bulkheads” would line the waterfront. Sheds and other structures would occupy the wharves, and stone, fireproof warehouses would serve as retaining walls for the Heights. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that this idea was also before its time.

Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont died in Brooklyn on August 11, 1838. Although his waterfront vision would soon become a reality, it would be ninety years before a pedigreed Brooklyn Heights cat started the ball rolling again on his vision for a public promenade.

This is such a wonderful article! As someone who walks the Promenade every day, this will only add to my enjoyment. Thanks