“Hurry up! There is murder at Herriman Avenue, Jamaica. The telephone receiver is off the hook and I can hear terrible screams and groans. Send the police department down quick.”

That was the breathless message that Lieutenant Louis Keppel of the Jamaica police precinct received shortly after midnight exactly one hundred years ago, on July 31, 1921. The voice was coming from a frantic telephone operator.

The alarms bells for the reserves clanged as the lieutenant pushed the button to summon additional help. Half a dozen police officers rushed to the station headquarters in the old Jamaica Town Hall building and buckled on their revolver belts.

Some distance away, the men could hear fearful crying, alternated by what sounded like stifled groans. As they formed a cordon around the house, they drew their revolvers.

They hammered on the door and a second later could hear a scuffling of feet while the horrible shrieking increased. “I hear feet,” one policeman said. “Watch out, he may run through the rear.”

With increasing impatience, they knocked on the door a few times. Finally, a man in pajamas opened the door. Upon seeing the uniformed force outside his door, he nearly collapsed.

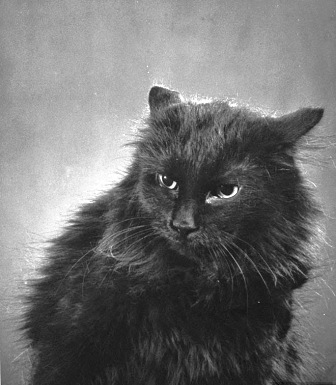

While one of the police officers held the man, another walked into the parlor, from where the sounds appeared to be coming. Seeing a set of gleaming eyes in the corner of the room, he flashed his light in that direction.

There on a small telephone table was a cat wailing the human-like cries. The receiver was off the hook.

“And to think,” said the telephone operator, “that I might have been a heroine.”

A Brief History of Herriman Avenue

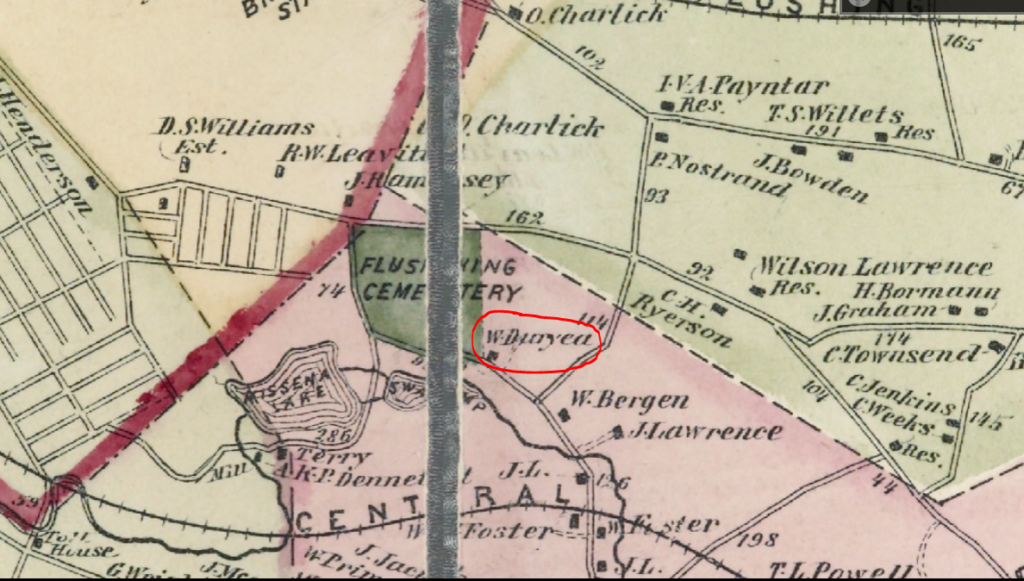

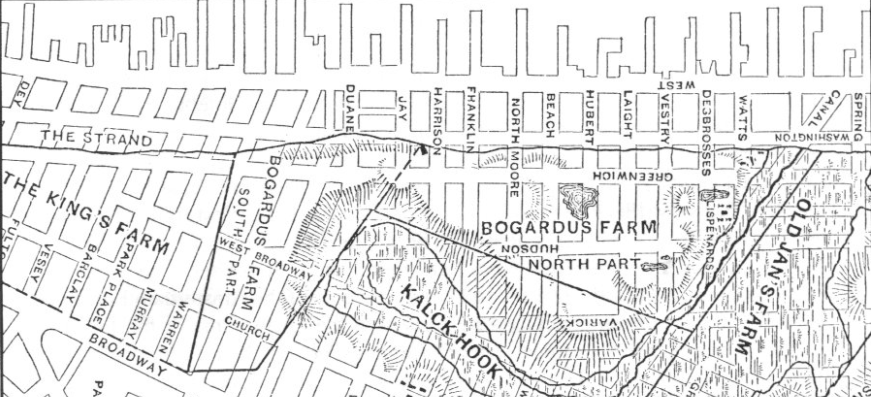

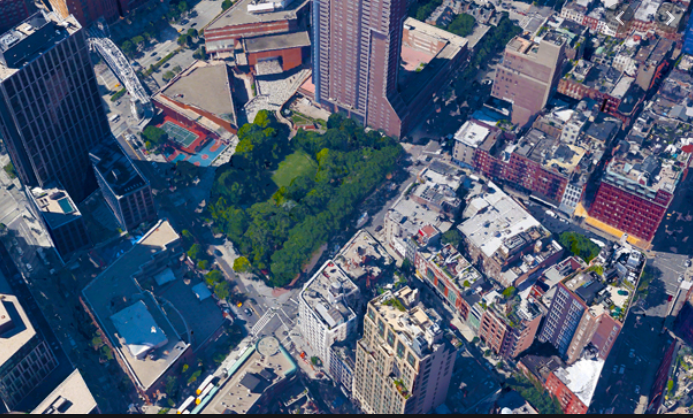

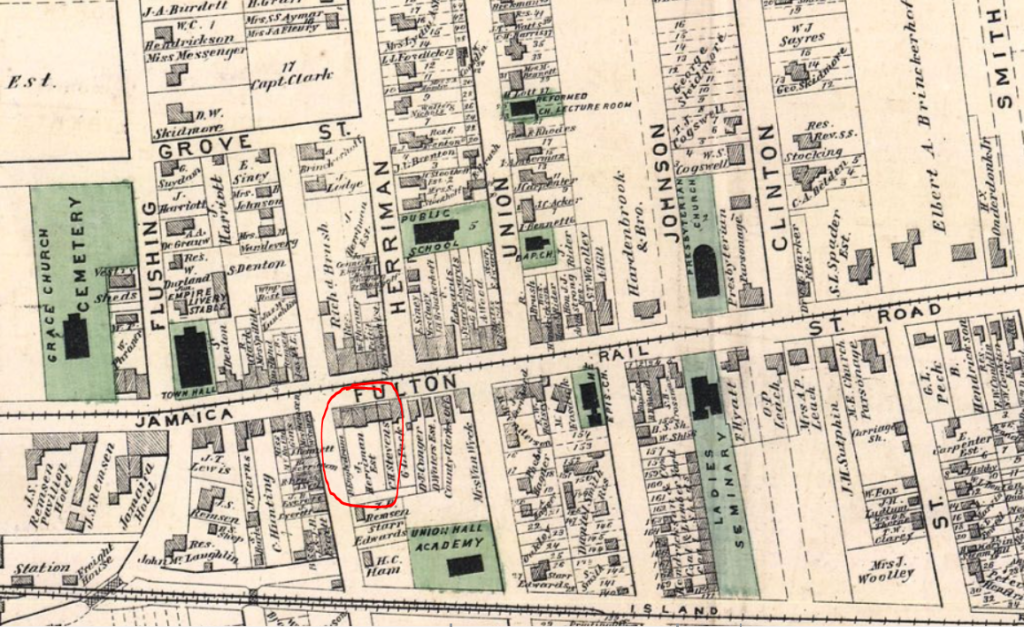

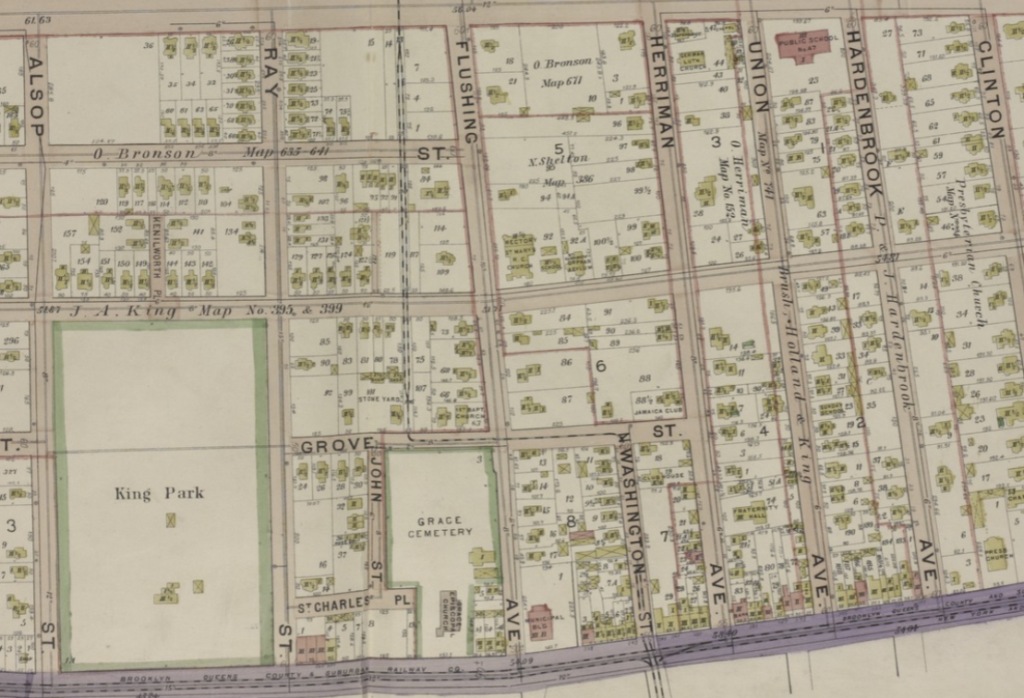

Herriman Avenue (now 161st Street) was named for James Herriman, who purchased a 40-acre farm on the north side of Fulton Street (Jamaica Avenue), just east of North Washington Street (now 160th Street) in 1792. Originally called Herriman’s Lane, the road led from Fulton Street to Herriman’s barn and then up the hill to the farm and beautiful woodland on the hill.

The name of the lane was changed to Herriman Avenue after it was opened and widened in 1854-55. During this time, Herriman Avenue was the most important business street in the village of Jamaica, and many prominent families lived on the avenue.

One of the important buildings constructed on Herriman Avenue was the public school, which was built in 1854 (noted on the map above and pictured below). This building later served as Fraternity Hall, aka Old Fellows Hall. It was demolished in the early 1900s.

In 1858-59, a town hall was erected on Herriman avenue, just north of Fulton Street. This was a wooden structure, two stories high, with a basement housing five cells and a police court room. The first floor was fitted up for town meetings and public business. The second floor was used for justices’ courts.

The old town hall was sold to John H. Brinkerhoff in 1870. He converted the building into private dwellings.

In 1870, a new town hall was constructed on the corner of Fulton Street and Flushing Avenue (now Parsons Boulevard). This building served as the civic center for all villages within what was then the Town of Jamaica.

After Queens County was consolidated into Greater New York City in 1898, the building also housed the 58th Police Precinct, a traffic court, and a small claims court. During this time, the Jamaica police station covered 35 square miles. (Consider that all of Manhattan is 22 square miles.)

Due to the high cost of maintaining the massive Victorian structure, it was demolished in 1941.

The Herriman Family

Very little has been written about James Herriman, but the family’s history goes back to 1620, when John Harriman reportedly landed at Plymouth Rock. In 1730, John Harriman’s grandson, Stephen, moved to Jamaica and changed his last name to Herriman. Stephen was the father of James Herriman, who was born in 1761.

James and his wife Magdalene had five children: Martha, James, Margaret, Stephen, and John. James died in 1801 at the age of 40 from yellow fever; his wife died in 1841.

Of the five Herriman children, only James II, born in 1790, stayed on the family farm in Jamaica. He and his wife had three sons (Charles, Joseph, and James Augustus) and two daughters (Catherine and Mary).

According to an 1850 census report, James reportedly grew wheat, rye, and corn on the farm. The Herrimans also owned two horses, two cows, and four pigs. In later years, the family sold off a large portion of the farm for building lots.

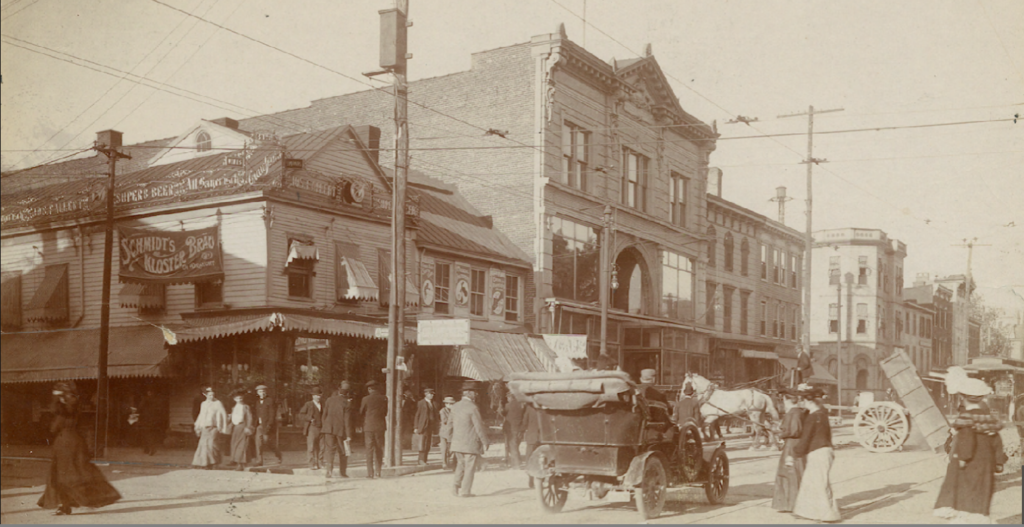

In addition to the farm, James also owned a dry goods and grocery store in a three-story brick building on the northwest corner of present-day Jamaica Avenue and 161st Street. (The old family barn was behind the store.) He ran the store with his brother-in-law and his neighbor Richard Brush; in 1836, his son James Augustus joined the business.

During the Civil War years, when James Augustus was serving as a general with the 87th Brigade of the New York Volunteers, Charles Herriman took over the business. James Augustus passed away in 1875 following a long illness.

In the photo above, the frame store on the left (corner of 160th Street and Jamaica Avenue) was owned by Richard Brush; his residence was to the right of that. James Herriman owned the remaining buildings on the block, including the store on the corner of 161st Street, his own residence to the left of the store, and the large buildings in the center, one of which was Mr. Watrons’ drugstore.

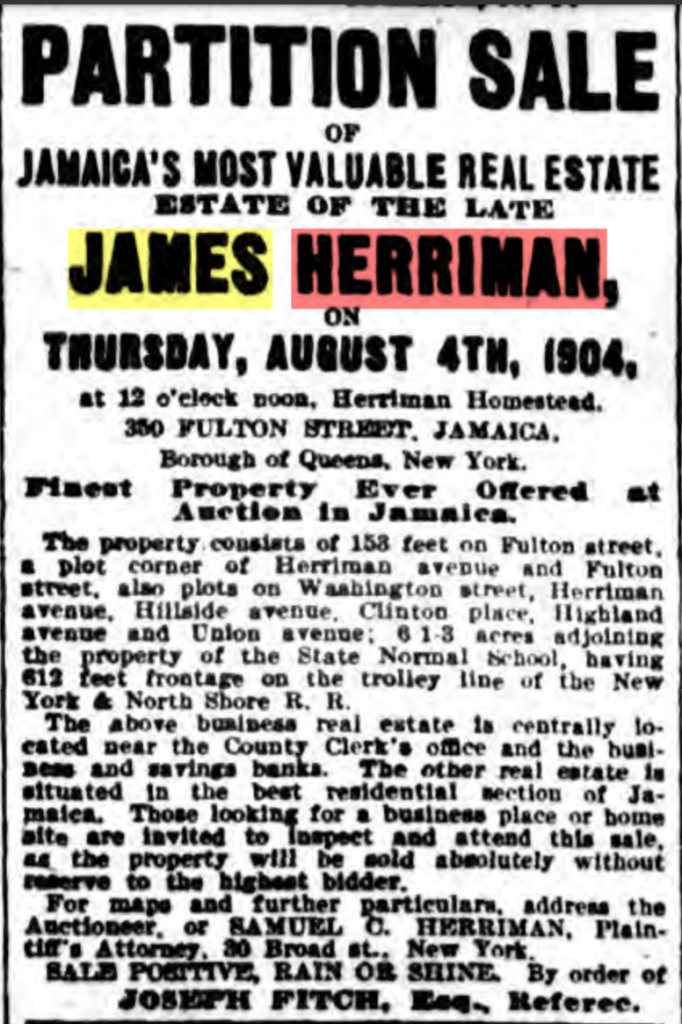

In addition to the block on the northern side of the street, James Herriman also owned ten acres of land on the south side of Fulton Street, where he built a block of six brick, three-story and basement houses. Over the years, this block of buildings became known as Herriman’s Brick Block. The Herrimans eventually lived in one of the large houses in the center of the block–the address was 350 Fulton Street.

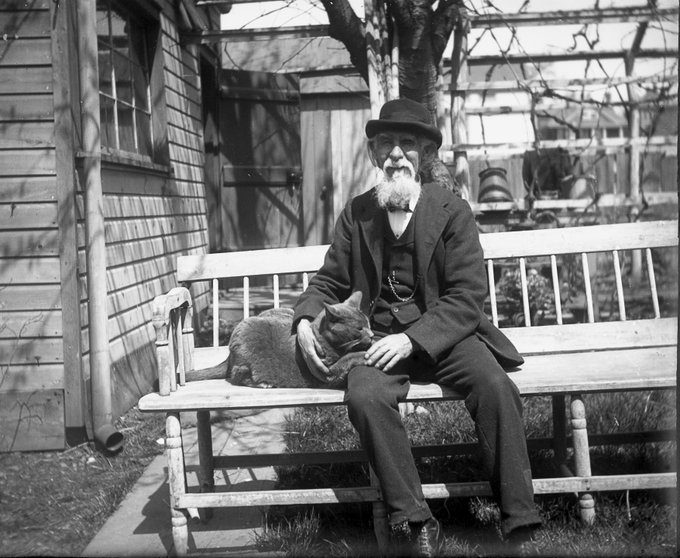

When James died in 1863, Charles sold the family store and got a job in Manhattan as a bookkeeper. Charles died in the Herriman family home on Fulton Street in October 1901 at the age of 71.

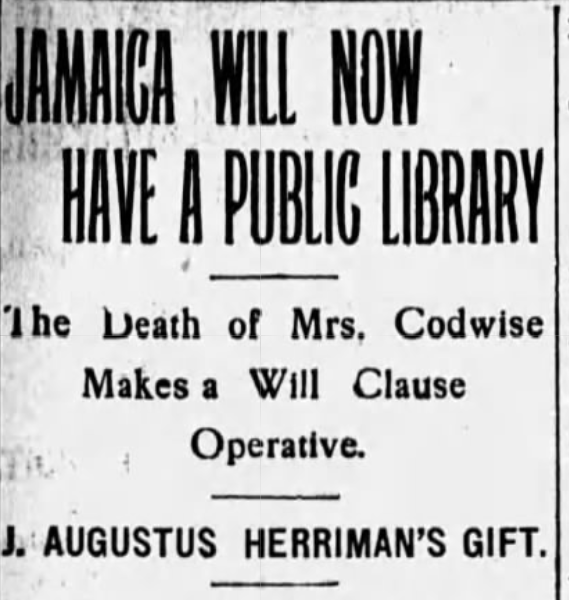

At the time of Charles’ death, only his sister, Catherine, the widow of George N. Codwise, was still alive. When she died in 1904, the Herriman estate was supposed to be bequeathed to the trustees of a new public library for the village of Jamaica called the Herriman Library.

According to the will of James Augustus, the library was to be housed in the stately Herriman family home on Fulton Street.

Unfortunately, the will was contested by several heirs (some distant cousins), and the library deal free through. The heirs sold the estate in a partition sale August 1904. James Augustus had made his living in real estate, so the property holdings were quite extensive, and extended beyond the village proper.

In 1919, many of the old street names in Jamaica, including Herriman Avenue, were changed to numbered avenues and streets; however, it would be a few more years before newspapers stopped referring to the old street names.

If you enjoyed this story, you may enjoy reading about Tipsey, a cat that helped solve a murder mystery in 1912.