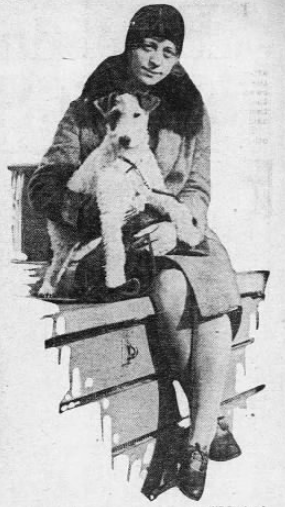

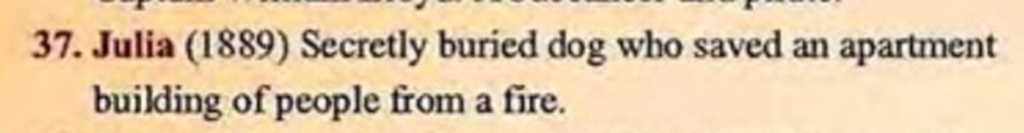

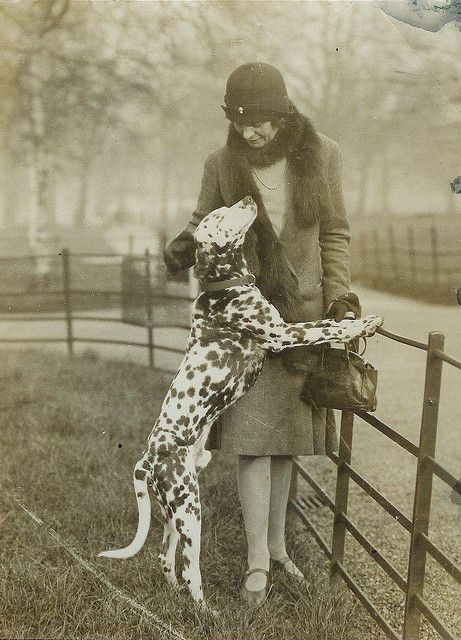

A few months ago, my friend Laurie Gwen Shapiro, a New York City author and documentary film maker, alerted me to a mystery story about a dog named Julia who was buried at Maple Grove Cemetery in Kew Gardens, Queens. All she had was the following, from a list of those buried at the cemetery. I told her I loved a good animal mystery and would have to look into it. What I found was a remarkable story about a woman named Marie Antoinette Nathalie Dowell Pollard and her lifesaving coach dog, Julia.

On January 29, 1885, Mrs. Marie Antoinette Nathalie Dowell Pollard, a lecturer, author, and widow of author Edward A. Pollard, was sitting up late writing in her home office on the second floor of 35 West 14th Street.

One floor above, C.Y. Turner, the proprietor of the artists’ studio on the top floor of the building, and his brother Thomas G. Turner, an electrician, were sleeping. Professor B.P. Worcester, in charge of the New York Choir School, was also in his apartment next to Mrs. Pollard on the second floor.

On the ground floor was E. D. Bassford & Co., a home furnishing store with storage in the basement. Other business tenants included the American Temperance Union, Keystone Lodge No. 230, the Mozart Music Union, and the New York Choir School.

On this winter night, Mrs. Pollard was working on her latest lecture, “The Glorious South of 1885.” She was so absorbed in her work that she lost all track of time. She also failed to notice that Julia, who was sitting next to her, was acting nervous and restless.

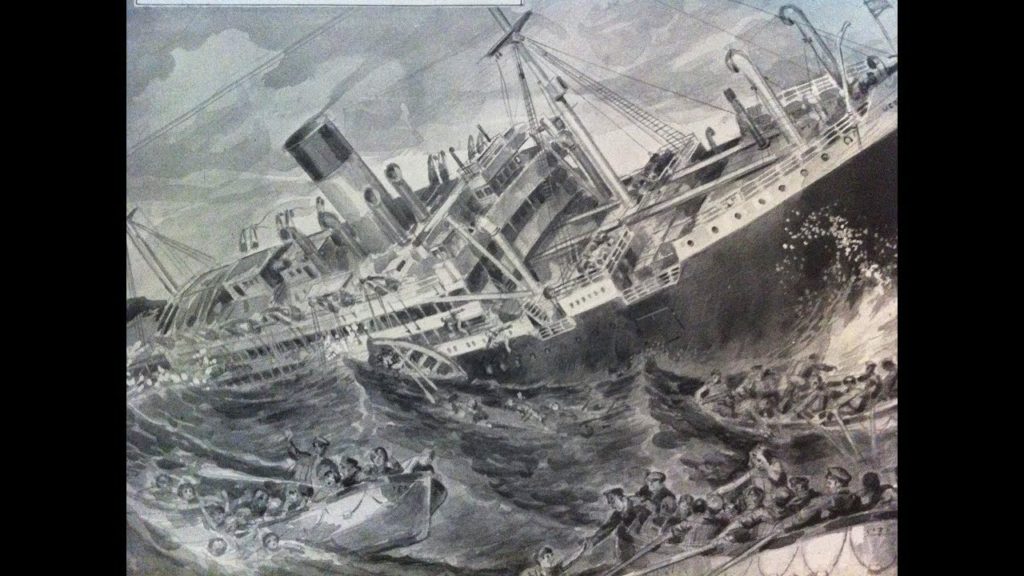

At about 1:30 a.m., Julia began barking and howling. At the same time, Mrs. Pollard noticed a slight haze in the front hall room. There was also a faint smell of smoke in the room.

She tried to open the door leading out of her office, but it was locked. In her panic, she could not find her key, which was in her pocket. So, she began pounding on the wall adjacent to Professor Worcester’s apartment.

The pounding aroused the professor, who opened Mrs. Pollard’s door and helped her into the hallway. Professor Worcester ran into the street and called in the alarm.

The pounding also woke up C.Y. Turner, who opened his door and found smoke and flames in the lower hallway. Convinced there was no way out via the stairs, he returned to his apartment and waited for the firemen to rescue him and his brother. In no time at all, the roof was in flames.

When the firemen arrived on the scene, they found Mrs. Pollard standing on the landing with her manuscript and Julia in her arms. The men helped her down the burning stairs while other firefighters set up ladders to rescue the Turner brothers from the top floor.

The fire had reportedly started in the furniture store, possibly from an overheated stove in the basement, and moved up the stairs. The furniture store sustained the most damage, while the apartments above sustained smoke and water damage.

Had Mrs. Pollard gone to bed earlier that night, or had she not owned a dog named Julia, the residents of 35 West 14th Street may not have been so lucky that night.

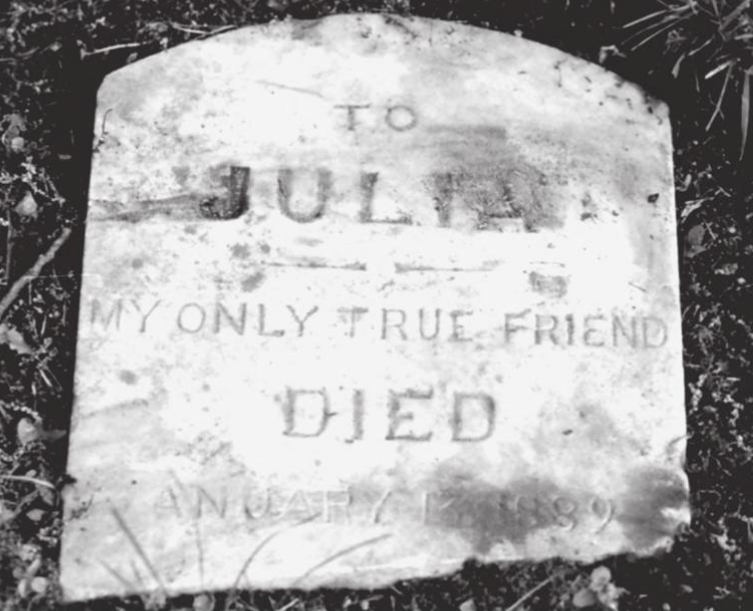

In January 1889, someone poisoned Julia. Mrs. Pollard hired undertaker Stephen Merritt to create a pink satin-lined casket for her beloved dog. She also reportedly hired professional mourners.

The funeral at Maple Grove Cemetery in Kew Gardens Queens, was kept secret, because burials of animals–such as the burial of Fannie Howe in Green-Wood Cemetery in 1881–was frowned upon. Thus, Julia was listed as a “secretly buried dog.”

Someday, when I go to Maple Grove Cemetery to visit the graves of my maternal grandparents and great-grandparents, I will search for this old grave of Julia, the lifesaving dog of Mrs. Pollard.

A Brief History of Mrs. Marie Antoinette Nathalie Dowell Pollard

Born on March 4, 1839, in Norfolk, Virginia, Marie Antoinette was the daughter of Colonel Pierre Joseph Granier (a French nobleman) and the Countess de Boussoumart. The family was driven from San Domingo and settled in Norfolk, where Marie Granier received training under the guidance of a governess.

Four years after her mother passed, when Marie was only 14, she married James Dowell, a division superintendent of what became the Western Union Telegraph Company. Marie and James had four sons and one daughter.

During the Civil War, Marie separated from James because of political differences. Their divorce followed a sensational trial. (Dowell reportedly kept a young man on watch at his office for fear that Marie would keep her promise and try to kill him.)

According to several news reports, Marie was a prisoner of war under Union General Nathanial G. Banks in New Orleans, charged with being a spy. Wearing men’s attire, she was able to escape to the swamps of Louisiana, where she survived on dry bread and stagant water for a week. After enduring many hardships and escaping death a few times, she finally returned to her home in Richmond, Virginia, only to find her home in flames.

Two years after her divorce, she married Edward A. Pollard (1828-1872), an author and wartime editor of the Baltimore Examiner who was a Confederate sympathizer and an advocate for white supremacy. After his death in 1872, Mrs. Pollard began her career as a lecturer and reader, touring Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York, San Francisco, and other cities around the country.

Mrs. Pollard was best known for her lectures on temperance and for her satires on social life in Washington. She also toured California on behalf of the Democratic Party ticket in 1876.

In 1893, Mrs. Pollard spoke at the Congress of Women at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Here is an excerpt from Mrs. Pollard’s Foot Free in God’s Country:

I would ask you to sum up, if you can, the amount paid in a single day for drink alone. Now let the mind go out, extend the vision and the sum to all the cities, towns, villages, hamlets and waste places in the republic, and put the sum total in figures and multiply it by the days in the year, and you have a sum greater than the revenue of the United States Government. And paid for what? For that which is related to no good and which is wholly and utterly bad.

Add the yearly waste for drink of all the years of human life on this continent and, if the mind can carry it forward, estimate the cost of drink for all the years of modern Europe, and you reach a sum which can hardly find expression in words and figures.

Give me what is thus expended in fifty years, with wisdom to rightly use it, and what would I not do? I would feed and clothe, nurse and house every wretched child of wretched mortal man and woman on the broad earth. I would build up schoolhouses on all hillsides, in all the pleasant valleys, on all the smiling plains known to man. I would hire men to do good until they should fall in love with goodness. I would banish that nameless sin, for every female child should be placed above want and be made mistress of herself, to be approached only for her purity; and man should come to seek and love woman for that alone.

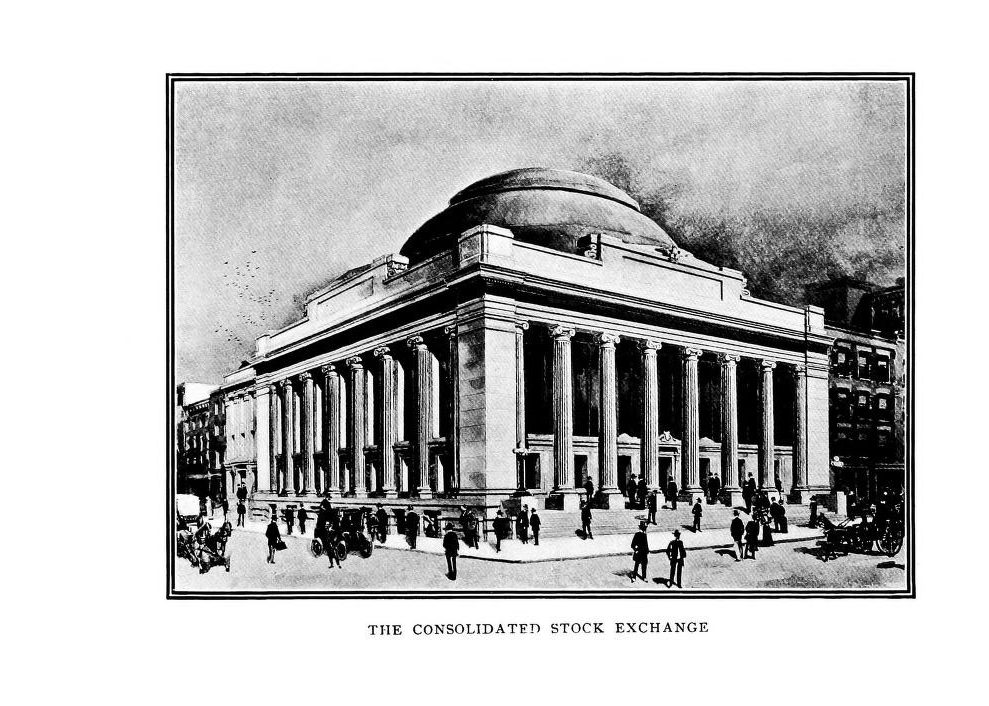

In 1890, a year after Julia’s death, Mrs. Pollard opened a broker’s office in the Consolidated Exchange Building at 60 Broadway for women who wanted to buy and sell stocks. Although she was a small woman, she had large ambitions to become the female Jay Gould, believing that women should be able to trade in stocks as well as men.

At the time she opened the office, Mrs. Pollard was still awaiting admission to the floor of the Consolidated Stock Exchange (she was the first woman to apply for a seat on the exchange, also called the “Little Board”). While she was waiting for the men’s decision on her application, she hired a man to execute her stock orders. She knew that the men were jealous of her early success (she reportedly made $20,000 mining “wildcat” stocks in California a few years earlier), and was worried they would not approve her application because of this.

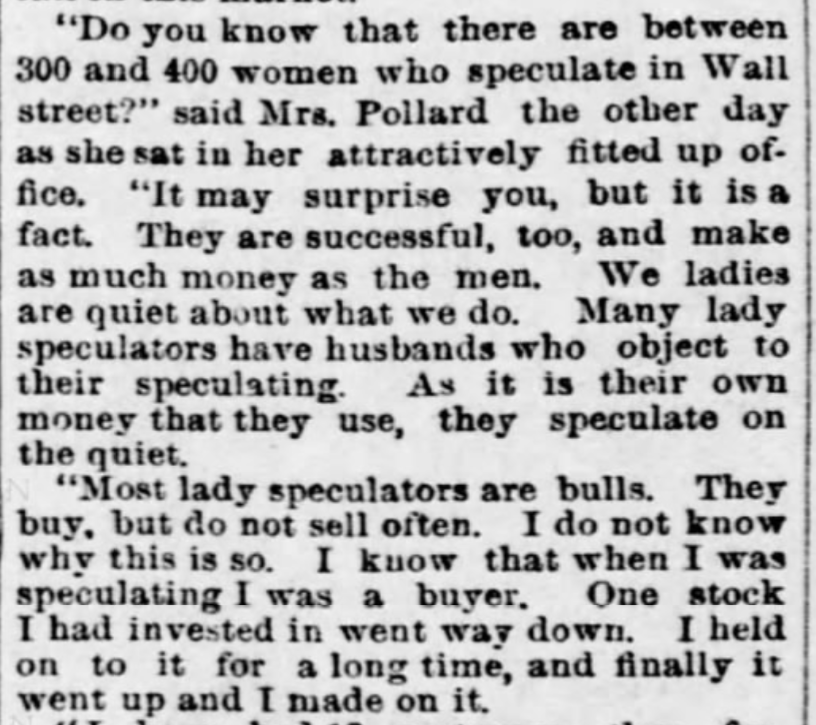

The following is from the Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 15, 1890:

I can’t confirm whether Mrs. Pollard was accepted to the floor of the exchange. However, I can confirm that she was feisty (perhaps this is why the press often referred to her as a “burlesque lecturer”). Not only did she reportedly attack Democratic Senator Graham Vest with a horsewhip while she was living in Richmond, she was also charged with shooting a druggist in Baltimore.

Apparently the druggist, Mr. Moore, had caused her late husband (Pollard) to separate from his second wife (Marie was his third wife). She went to the druggist’s office to save her husband from getting into bad habits again. The druggist interfered and tried to hurt her, so she took out her pistol and shot him in the hand. She was fined $100 for shooting the druggist.

Sometime around 1893, Mrs. Pollard moved to Europe. She died on December 6, 1900, following a carriage accident in Paris (the carriage ran over her). At the time of her death, she had at least two surviving sons and several grandchildren in America. Maybe one of her great-great grandchildren will come across this story some day.