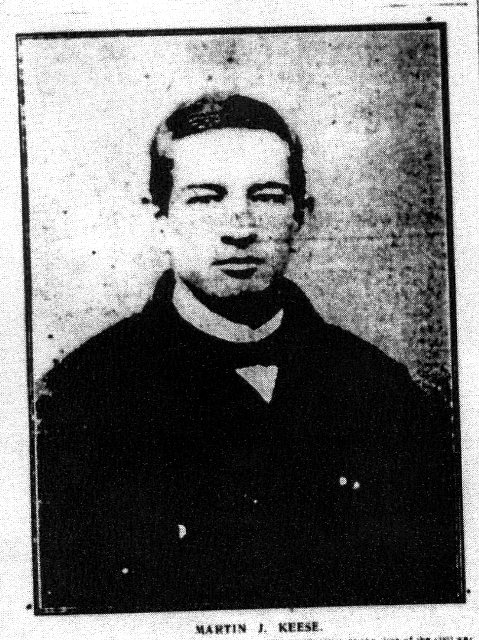

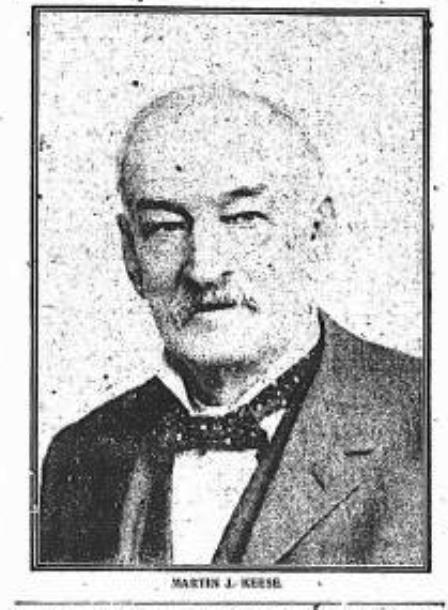

The following story is dedicated to the family of Martin J. Keese, the most famous custodian of City Hall in the history of New York.

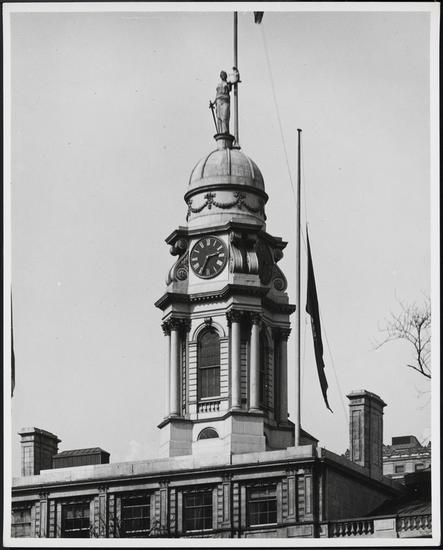

It was a cold and wet day in 1891 when the homely tabby kitten with white paws first tried to make New York’s City Hall his manor home. Somehow he got the nerve to march up the steps and enter the front door, saunter down the long hallway, and calmly begin to lick his fur dry. Since it was the end of December, I have a feeling his subsequent attempts to move into City Hall ended with the same paw-licking routine.

Martin J. Keese, the City Hall custodian and janitor, tried many times to shoo the cat outside. He even tossed the kitten from a window a few times. But even Marty – the man who once fought with the First Fire Zouaves in the Civil War, who met Abraham Lincoln, and who, as a deputy sheriff, arrested William “Boss” Tweed – couldn’t keep the defiant kitty away. As the children’s camp song goes, the cat came back the very next day, the cat came back, he just wouldn’t stay away.

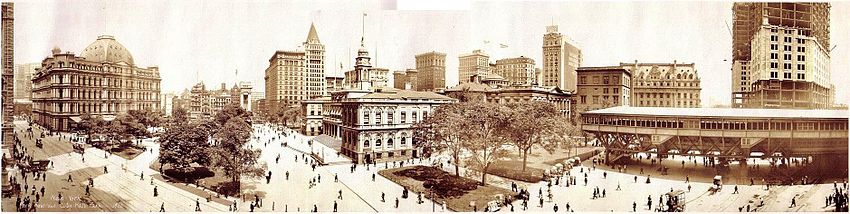

Marty was no stranger to the many cats that hunted for sparrows in City Hall Park. By the time “Tom” arrived, Marty had been living with his children on the top floor of City Hall for ten years. His youngest daughter, Marie (Dollie) loved cats, and would feed the many forlorn felines that temporarily evaded Marty’s keen eyes and escaped inside City Hall.

Tom the tabby must have been very determined, because he prevailed. (As a reporter for The New York Times said, he was “a fine example of the self-made American cat.”) City Hall was his kingdom for the next 17 years.

From Mayors Grant to McClellan

In 1891, Hugh J. Grant was in his third year as the 88th mayor of New York. A graduate of Manhattan College and a Tammany Hall Democrat, he was the youngest mayor in the city’s history when he took office at the age of 31. Grant would be the first of six mayors to serve during Tom’s long rein as the city’s official mascot. During his tenure, Tom also shared his City Hall home with mayors Thomas F. Gilroy, William L. Strong, Robert A. Van Wyck, Seth Low, and George B. McClellan.

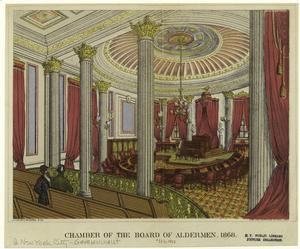

Life was good for the City Hall pet cat. Over the years, the tabby cat befriended many of the men on the Board of Aldermen and City Council. He often slept in the aldermen chambers during board meetings, and he loved sitting on the desk of City Council President Randolph Guggenheimer.

Tom was especially fond of the council president, and the feelings were apparently mutual: Guggenheimer spent fifty cents on a special dinner for Tom every Christmas.

In winters, Tom often slept by a radiator in the basement or passed the time in the City Marshall’s office. When spring arrived, he’d deliver the authoritative message that winter was over by ambling down the City Hall steps and sunning himself on the asphalt pavement of the plaza.

In warm weather, Tom liked to visit his girlfriend cats on the feline police squad at the General Post Office. He also enjoyed taking dips in the park fountain and hunting for sparrows. Men and boys would often stop to watch the king of the sparrow hunters in action and make bets on whether cat or bird would prevail. When Tom won the fight, he’d bring the poor dead bird to the mayor’s office — Mayor Strong was one of his favorites.

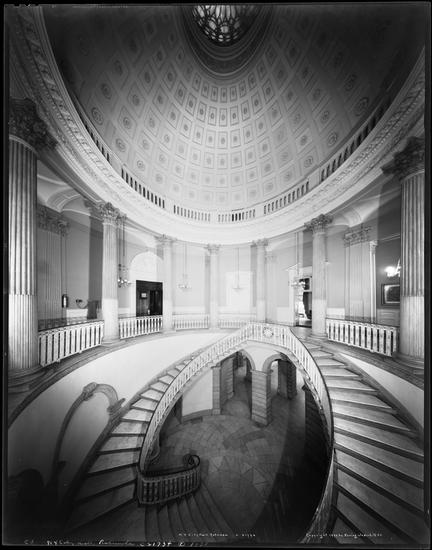

Their Private Mansion

Working as the custodian for City Hall also had its perks. Consider that on weekends, holidays, and after hours, City Hall was the private mansion for Marty; his mother-in-law, Isabella Dunn; and his four children, William R., Elizabeth A. (Lillie), Charles W., and Marie L. (Marty’s wife of 23 years, Sarah Starr Dunn, died in 1883.) They made their home in the custodian’s apartment under the City Hall dome, which was located at the top of 38 stairs in the building’s third-floor rotunda. Lace curtains on the windows and flowering plants gave the odd space a homelike look and feel.

Their Final Years

On June 25, 1906, Marty and some of the aldermen had a party for what The New York Times called “the looter of the city feed bag at City Hall.” Marty picked up the 15-year-old tabby from the rear steps and escorted him to the hall, where Alderman Frank Dowling and a committee of veterans were waiting for him. Each man shook Tom by the paw and then he was served some porterhouse steak.

By this time, Old Tom was deaf and feeble, and could no longer hunt sparrows. Keese took over feeding the cat, and when Tom was thirsty, he’d push open the door to the reporters’ room and drink from a can that was kept in there for him.

Marty was also starting to feel his age, and often struggled making his way up the iron spiral staircase to his apartment. As they aged together, Tom and Marty both enjoyed sunning themselves on the steps of City Hall.

On July 22, 1908, Marty knew it was time to put Old Tom out of his misery. He called for the SPCA, but they told him no one was available to take the cat.

Policeman Joseph Cahill of City Hall Station responded to his call for assistance. He led Old Tom into the park, and, as humanely as possible, put an end to the mascot’s life. Marty and several politicians stood by to pay tribute to the famous sparrow hunter and City Hall mascot.

Eleven months after Old Tom’s demise, and a day before what would have been his 72nd birthday, Marty Keese died of acute bronchitis at St. John’s Hospital in Long Island City. His half-brother, Edmund Rogers, was at his side when he died. At the time of his death, Martin Kleese’s apartment in City Hall was filled with relics, scrapbooks, and cats. Lots of cats.

Apparently Old Tom and his feline friends had turned Marty into the male equivalent of a crazy old cat lady.

Marty’s replacement was an elderly man named John Ryan, who was forced to leave the apartment when the Design Commission took over the space in 1914. Apparently, like Tom, he was determined to stay. In the end, he had to be evicted and carried out on a chair.

The Most Famous Janitor of City Hall

Note to reader: The story of Old Tom ends here, but if you love history, you may be interested to read more about Marty Keese, as reported in numerous articles in The New York Times. I think his life was incredibly fascinating. Let me know if you agree.

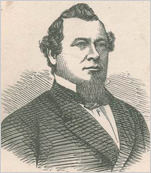

On June 28, 1909, a day after his death, The New York Times wrote the following about Marty in a lengthy memorial to the famous custodian:

“Marty Kleese, as the aged janitor of the City Hall has been known to Mayors, Aldermen, politicians, and newspaper men who have come and gone there for more than a quarter of a century, had a most interesting history. He was probably more closely identified with the important events of the city in the last fifty years than any other man living.”

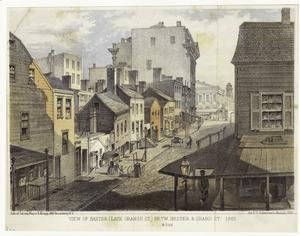

Marty was born on June 27, 1837, in a little brick house at the corner of Grand Street and Laurens Street (now West Broadway). He attended school at Mrs. Weston’s frame schoolhouse on Orange Street (now Baxter), which cost his mother one penny a day.

As a child, Marty and his older brother, Billy, liked to ride on the pigs that roamed freely through City Hall Park. “It was one of the principal amusements of us boys,” he wrote in one of his scrapbooks.

Marty also enjoyed following the volunteer firemen of United States Engine 23, which was then located on Anthony Street (now Worth Street), just west of Broadway. He and his friends would trail the firemen on their calls, whooping and hollering after their idols.

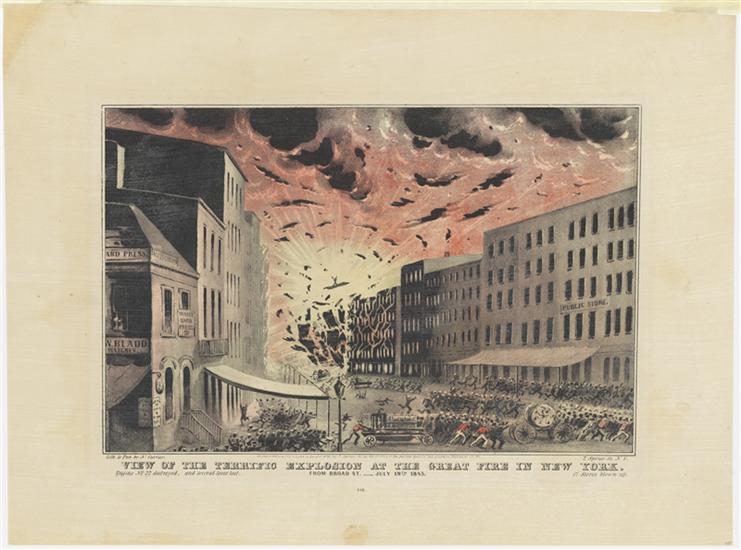

On the night of July 18, 1845 – the night before the third Great Fire of New York began – 8-year-old Marty reportedly got into a fight with one of the lads who ran with Phenix Engine Co. 22.

Martin ended school at a young age and was trained in brass polishing and finishing. He got his first job at the William F. Ford surgical instrument factory in the early 1850s, and later started a business manufacturing plumbers’ materials. He also officially joined New York’s Volunteer Fire Department, first as a runner with Fulton Engine Company 21, and then as a member of the M.T. Brennan Hose Company 60 in 1858.

He married his wife, Sarah Starr Dunn of Halifax, Nova Scotia, two years later. They lived at 117 White Street and later, at 621 Pearl Street.

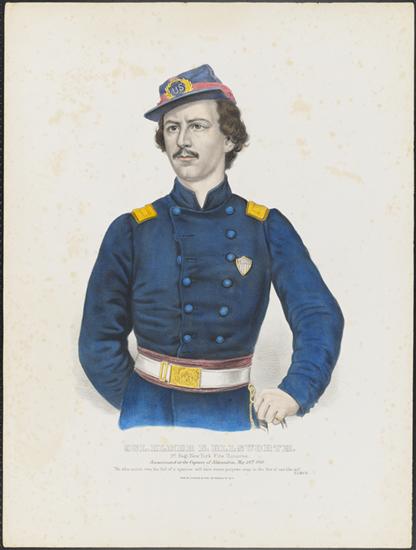

In the spring of 1861, Marty enlisted in Company F of Col. Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth’s 1st Fire Zouaves, more formally known as the 11th New York Voluntary Infantry Regiment. This regiment of 1,200 New York City volunteer firemen was attacked during the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 as it guarded the retreating Army of the Potomac.

Marty was seriously injured in this battle by a shot to his side; his friend Tommy Curry, and his brother, Billy, both died of injuries sustained in the war.

Despite his injuries, Marty returned to New York and fought with the soldiers and firemen during the Draft Riots in 1863. He was also elected foreman of M.T. Brennan Hose Co., a position he held until the volunteer fire service was disbanded in 1865. Sometime in the 1860s, he accepted the position of deputy sheriff under Sheriff Matthew T. Brennan.

On December 16, 1871, Deputy Sheriff Keese arrested William “Boss” Tweed in his suite (#114-118) of the Metropolitan Hotel.

Tweed had just returned from his country home in Greenwich, Connecticut, and according to Keese, he said he just couldn’t keep away from the bright shop windows during the holidays even though he had a feeling he was going to be arrested.

Tweed was convicted on 204 of the 220 charges against him, and sentenced to 13 years in debtors’ prison. “I felt sorry for him,” Keese told reporters many years later.

Marty also made the headlines when he became the first New Yorker, other than the news reporters, to pay the penny toll to cross the Brooklyn Bridge.

At midnight, when the bridge was first opened to the public, the men raced to cross the bridge. Marty, wearing his best suit for the occasion, came in second place. As the story goes, Marty and one of the reporters forgot about the toll going back, and had to borrow a penny to cross back to Manhattan.

Marty’s legacy with the firefighting services is also commendable. He was one of the principal organizers of the Exempt Firemen’s Association and president of the city’s Volunteer Firemen’s Association. Together with George W. Anderson, who rode with the Phoenix Hose Company 22, he also helped found the Fireman’s Home in Hudson, New York, for sick, disabled, and indigent firefighters.

Today, the Firemen’s Home is a certified residential healthcare facility, and serves as the grounds for the Museum of Firefighting as well as the Firefighter’s Memorial.

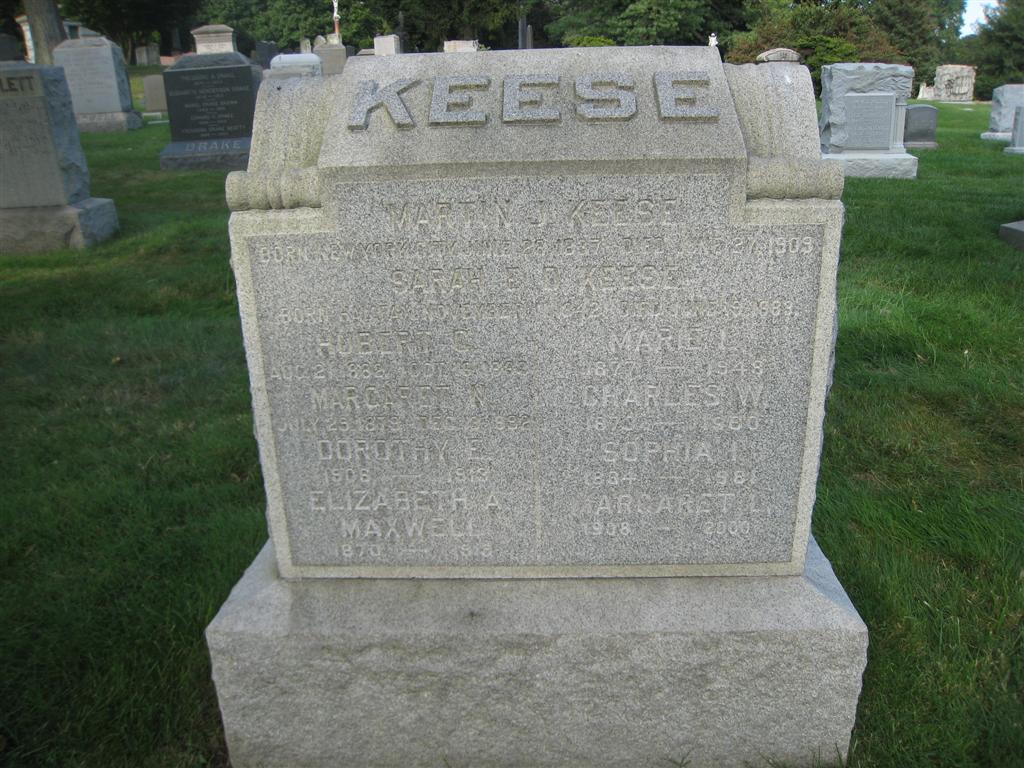

Marty Keese was buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery: In his will dated May 28, 1909, he asked to be buried as close to the plot of the Volunteer Firemen’s Association as possible. His final wish was fulfilled.

Really enjoyed this. Marty Keese and his cat, Tom, are true real-life characters; both had wonderful lives. Thanks.

This was one of my favorite stories, too. City Hall actually had several feline mascots in the early 1900s after Tom and Marty passed away, so you can be sure I will be writing stories about those cats, too.

[…] http://frenchhatchingcat.com/2014/01/03/tom-cat-pet-of-city-hall/ […]

[…] http://frenchhatchingcat.com/2014/01/03/tom-cat-pet-of-city-hall/ […]

[…] 1891: Old Tom Cat, the Brazen Pampered Pet of New York City Hall […]

Reblogged this on ellenlobb.

Marty Keese is my great grandfather, and I was totally suprised to receive this story from my sister. We grew up hearing the stories of City Hall, but the cat part is new to me! I learned some things about my family; I never knew Aunt Dollie was really named Marie, but I remember visiting her at her summer home. Charles is my grandfather;; he brought my grandmother Sophia to City Hall to live and to help take care of Marty in the early days of their marriage.. My aunt Margaret Keese was born in City Hall. There were 6 children in all, but Dorothy died young of diptheria. Three of the children lived until their 90’s, my mother Edith Keese Lobb living to 96. She would have been thrilled to see this story. You did a great job!!!

How wonderful! Your reply made my day!

I love doing all this research and sharing these stories with others, and my wish is to have readers like you — ancestors of all the people in my stories — come across this blog and make a discovery about a family member. Marty’s story was especially appealing to me because I am also a volunteer firefighter in the Hudson Valley, and I am very familiar with the Firemen’s Home that he helped establish. He had an amazing life, and I hope to someday check out where he once lived atop City Hall.

If you have any real photos of Marty or his family that you’d like to share here, please let me know — the two photos I have of him were taken from news articles so they’re not very clear.

Thank you again, and I hope you share this with others in your family.

Peggy

Dear Peggy,

I am delighted with the feelings the article has stirred up. Although Martin J Keese died long before I was born in 1944, his memory was very alive in my family. When I was in high school I had the original copies of letters he wrote to my great grandmother, Sarah Elizabeth, during his time in the Civil War. They made for very interesting history lessons! The whereabouts of those letters is unknown at this time, although a cousin, Gary Keese Damon, thinks he may have them among the papers he has which came to him after the death of his older brother Gordon. Gordon might have found them when he cleared out the house of our aunt, Margaret Louise Keese, after her death.Many years ago my mother, Edith Keese Lobb, transcribed those letters, and I do have copies of them. I will be happy to copy them again and send them on to you.

The tradition of firefighting was also very alive, as my father, Richard Tamblyn Lobb, was a New York City firefighter for over 20 years; my son, James Tamblyn Kotter, is a San Francisco firefighter currently, and my nephew, Richard Lobb Utne, was a firefighter in the Norwegian Navy, and has a career in fire equipment today.. My mother, Edith Keese Lobb, had a wonderful composite picture with Martin, Richard, James and Chad in their uniforms and with various emblems of firefighter units.. I guess some things are in the blood.

I called two of my cousins last night to tell them of the article and to get their email addresses so I could send it on to them. It felt wonderful to connect! The family is far flung these days, but we were close as kids. I imagine you may be hearing from them. Thank you again for starting the ball rolling down memory lane.

Sincerely,

Priscilla Lobb Kotter, known now as Perci Kotter

Perci, right after you wrote, I received a photo from City Hall that they said I could post with this story. I just added it, so please take a look — I’m pretty sure this is your great grandfather, but can you identify the two women in the photo?

I’m sorry, but I don’t recognize either of the women in the photo.

Sent from my iPhone

Hi Peggy, Love this post. I’m Perci’s sister and as she said, Marty was our great-grandfather. He died well before any of us were born but we all felt like we knew him through his Civil War letters and diaries. When we studied NY history in 8th grade I was given the assignment to write a report on Tammany Hall. Imagine the teacher’s surprise when I turned in a paper that consisted of diary entries detailing the arrest of Boss Tweed. Needless to say I got an A and the teacher kept the paper for future classes.

I believe one of the women in the photograph is Dollie. I’m pretty sure I have a copy of the photo somewhere in my mother’s things, I know I’ve seen it before. If I find it and it’s marked on the back I’ll let you know.

We have copies of Martin’s obituary that ran in newspapers throughout the US and Europe. I’d say that’s an indication he was not your run of the mill janitor.

[…] recently wrote about Old Tom, who was a very popular mascot of New York’s City Hall in the early 1900s. Although several other […]

[…] catch some sparrows, or maybe swap stories while soaking up the sun with the park cats or with Old Tom, the official cat mascot of City Hall. (Naturally, the park cats wanted to win a job at the post office, so they were on their best […]

Was your uncle Tony Lobb?

That last post was for Susan Lobb-Porter. Thanks.

Yes, Tony Lobb was my uncle. My dad, Richard T Lobb, and Tony were brothers. I am Susan Lobb Porter’s sister, my given name was Priscilla Ann Lobb. Did you know Uncle Tony, and what was your connection?

Hey Shaun–Yes, Tony Lobb was our uncle. You know the family?

[…] — but he knew there was no way she could stay at City Hall. After all, City Hall already had Tom, its brazen feline mascot, and Tom would never have accepted another cat in his territory. So Mayor Gilroy sent Bridget to […]