On September 26, 2016, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation giving non-for-profit cemeteries the option to honor the last wishes of New Yorkers who want to be buried with their pets. The law allows pet owners to inter the cremated remains of their pets alongside them—provided they obtain the cemetery’s written consent (religious cemeteries are exempt). The legislation also gives New York residents an alternative to pet cemeteries or backyard burial grounds.

No Proper Burial Options for Pets

Now step back in time to the 19th century and earlier, when the only option for New York City pet owners without the means to pay for a country burial was to toss their deceased pets into the rivers or street gutters. Horse-cart drivers employed with the New York Rendering Company would take the dead animals to the city’s offal dock on the Hudson River at the foot of 38th Street.

There, along with the carcasses of horses, cows, hogs, and other livestock, pet dogs and cats would be skinned and boiled into minced meat and fertilizer, or simply carted off with the city refuse to Barren Island.

For those New Yorkers who owned country estates outside of the city confines, private backyard burials were common. Some prominent residents also buried the family pet in the family plot, much to the dismay of the other plot owners.

For example, Gypsie, a black and white Newfoundland owned by Brooklyn artist Lemuel Wilmarth, was buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery in 1879. Fannie, a pure-bred Pug of nondescript color owned by Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine (no, it wasn’t Singer), was also interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in 1881.

Then there was Mary A. Lawrence Bell, who tried to bury Cozey Bell, a female Skye terrier, at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx in 1888. This is their story.

Mary, Edward, and Cozey Bell

Mary Bell was the daughter of Judith and Dr. James Lawrence of Luzerne, New York (Warren County). She was also the widow of Edward David Bell, a Boston widower and wealthy dry goods merchant who was the first person in the country to specialize in cotton hosiery. According to census reports, Mary and Edward married on May 31, 1880, when Mary was about 42 and Edward was about 60 years old.

The Bells did not have children (Edward’s first wife, Helen “Nellie” Hanscom, had died childless in 1871 at the age of 32). Edward–who had become paralyzed in 1865–had a Skye terrier named Cozey who was about 8 years old when he and Mary were married.

Edward died in their home at 81 Fifth Avenue four years later on August 5, 1884. He was buried in the Lawrence family plot at the Lake Luzerne Cemetery (the Bell family plot at Trinity Church in Boston went defunct prior to his death.) Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Bell began running a boarding house in a four-story brownstone at 62 West 38th Street. She became very attached to her husband’s beloved dog.

When Cozey was diagnosed with heart disease in 1888, Mrs. Bell hired three doctors to attend to her. One of the doctors was Herbert M. King, who lived on the parlor floor of Mrs. Bell’s boarding house.

Despite the medical care, Cozey died from heart failure on August 12. Overcome with intense grief, Mrs. Bell immediately contacted undertaker James Edward Winterbottom. She then placed Cozey’s body on ice as she made preparations for a proper burial at Woodlawn Cemetery.

Winterbottom presented a certificate of death to Dr. John T. Nagle at the Health Department’s Bureau of Vital Statistics. He also asked for a burial permit at Woodlawn Cemetery, where Mrs. Bell had purchased a plot for her beloved pet for about $135. (Apparently the rules of the cemetery stated only that the cemetery “was for the burial of the dead,” so Mrs. Bell assumed that applied to dogs as well as to humans.)

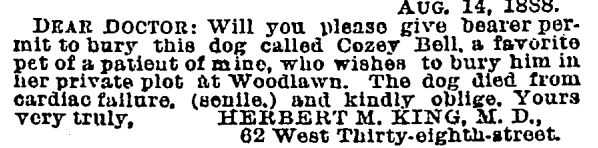

Dr. Nagle asked for the names of the parents of the child before he read the following letter and realized that the certificate was for a dog:

Dr. Nagel was reportedly quite amused by the letter. He told Dr. King that the Board of Health did not issue burial permits for dogs, and that no permit was required as long as the cemetery authorities did not have any objections to burying the dog at Woodlawn.

The undertaker told Dr. Nagle that he had not received any objections from the cemetery authorities. However, he did want a letter from the doctor to satisfy the railroad authorities of the New York and Harlem Railroad so they would not object to transporting the casket to the cemetery.

While undertaker Winterbottom worked on getting the paperwork, Mrs. Bell began preparing Cozey’s body for the burial. (I love his name; he sounds like a character from a Harry Potter book.)

She ordered a child-size, chestnut casket made in Rochester, New York, which was covered with embossed royal purple velvet and lined with light blue satin (with tufted purple satin on the lid). On the outer lid was a silver plate on which was engraved her name and the date of her death.

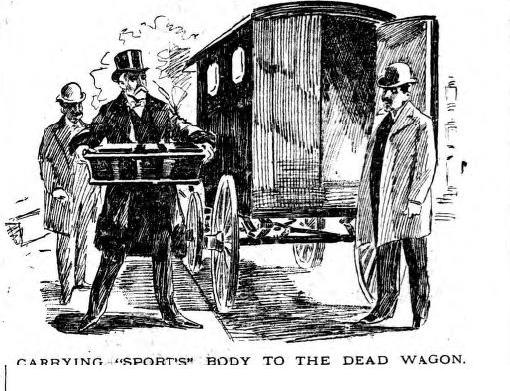

On August 15, the morning of Cozey’s burial, Mrs. Bell neatly parted and perfumed the dog’s curly hair and placed her head on a pink satin pillow. A funeral possession comprising Mrs. Bell, two women, and a man proceeded up Fifth Avenue to Grand Central Station, where they accompanied the casket on the 5:15 p.m. train to Woodlawn Cemetery.

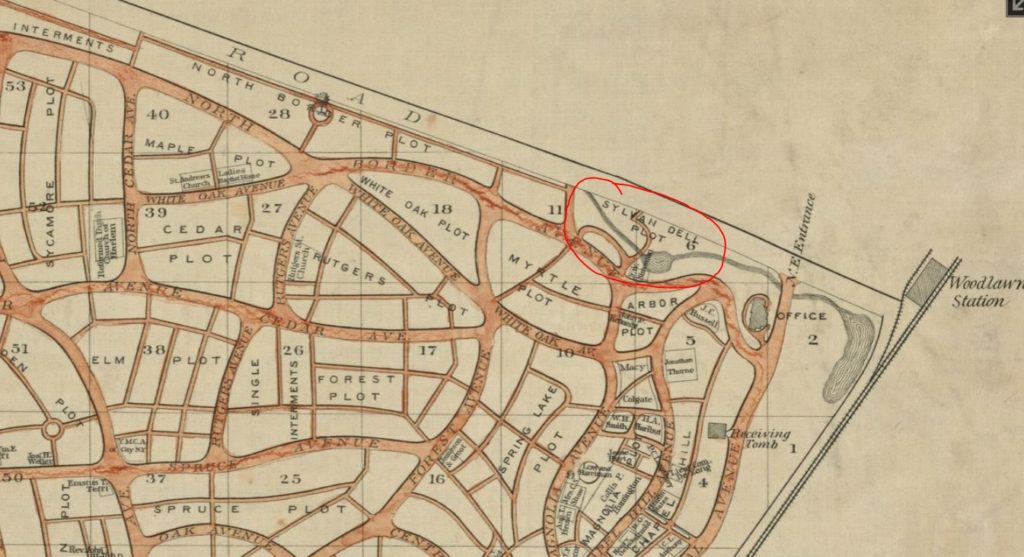

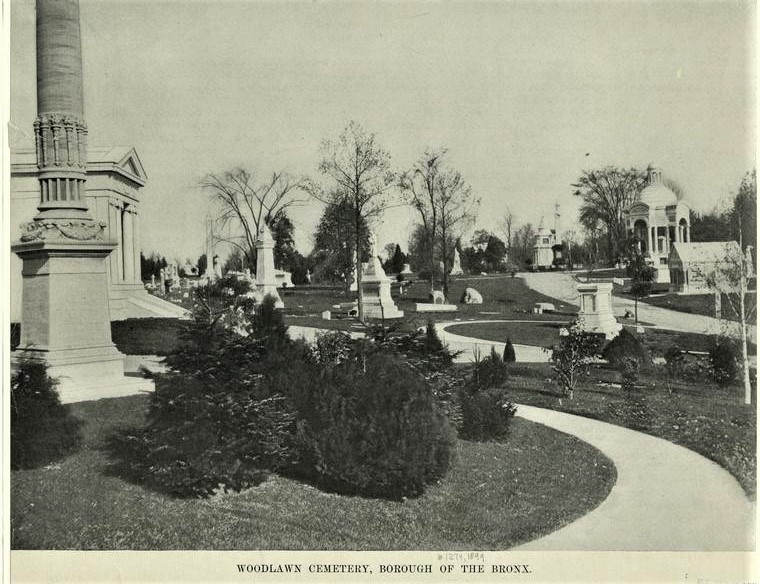

At the cemetery, a tent was stretched out on the lawn near the pond in the Sylvan Dell Plot, which was reportedly where many costly plots were located. Mrs. Bell read a eulogy, and the casket was opened one last time for everyone to say their final goodbyes to Cozey.

(The brook and pond in the Sylvan Dell were gone by 1912, according to a map published that year.) NYPL Digital Collections

In addition to the casket, Mrs. Bell had purchased a marble sarcophagus mounted on four pillars at the marble yard near the Woodlawn railroad station. The entire cost of the burial, including the monument, plot, and undertaker fees, was reportedly $500.

After burying Cozey at Woodlawn Cemetery, Mrs. Bell told the press that she intended to exhume her husband’s body from his grave in Lake Luzerne, and have him re-interred alongside his beloved dog.

Before I tell you what happens–remember, the title of this story says “Almost Buried”–here’s a brief history of the cemetery to better set the scene and to introduce you to the main characters involved in Cozey’s final outcome.

A Brief History of Woodlawn Cemetery

the consolidated City of New York was established, including the Bronx as one of the five distinct boroughs. NYPL Digital Collections

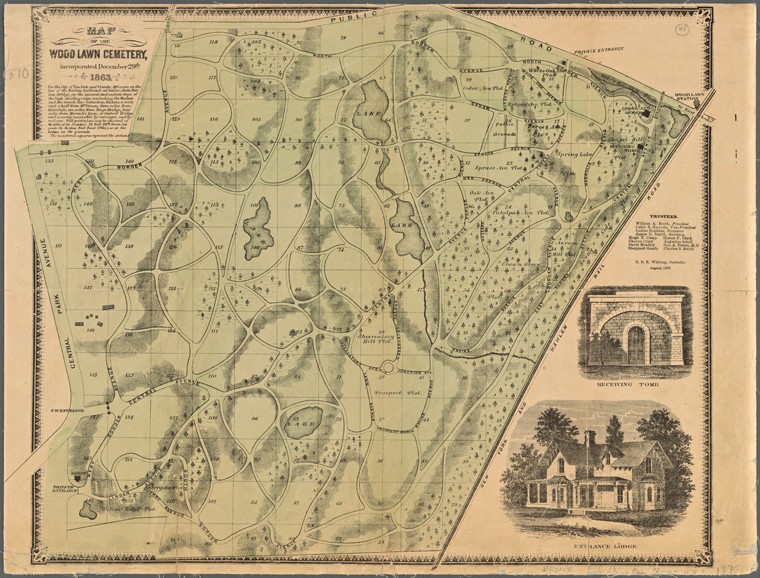

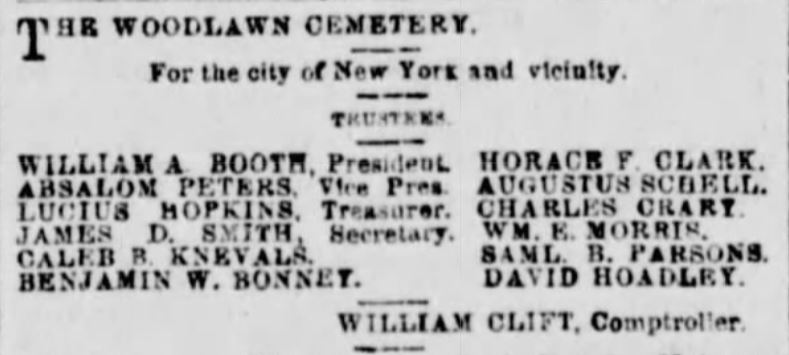

Woodlawn Cemetery was the vision of Reverend Absalom Peters, a theologian and poet who had dreamed of developing a rural cemetery for residents of Manhattan and Westchester County (which then included the the Bronx). His plan was to create a cemetery that would be developed and administered by a Board of Trustees authorized by law to accept endowments and and bequests in trust.

In the early 1860s, Peters assembled a group of prominent New York businessmen, who all agreed that the city’s churchyards and existing public cemeteries would soon reach their capacity. At their first official meeting on December 29, 1863, the men adopted “The Wood-Lawn Cemetery” as their corporate name (soon after changed to Woodlawn). They established their offices at 48 East 23rd Street in Manhattan.

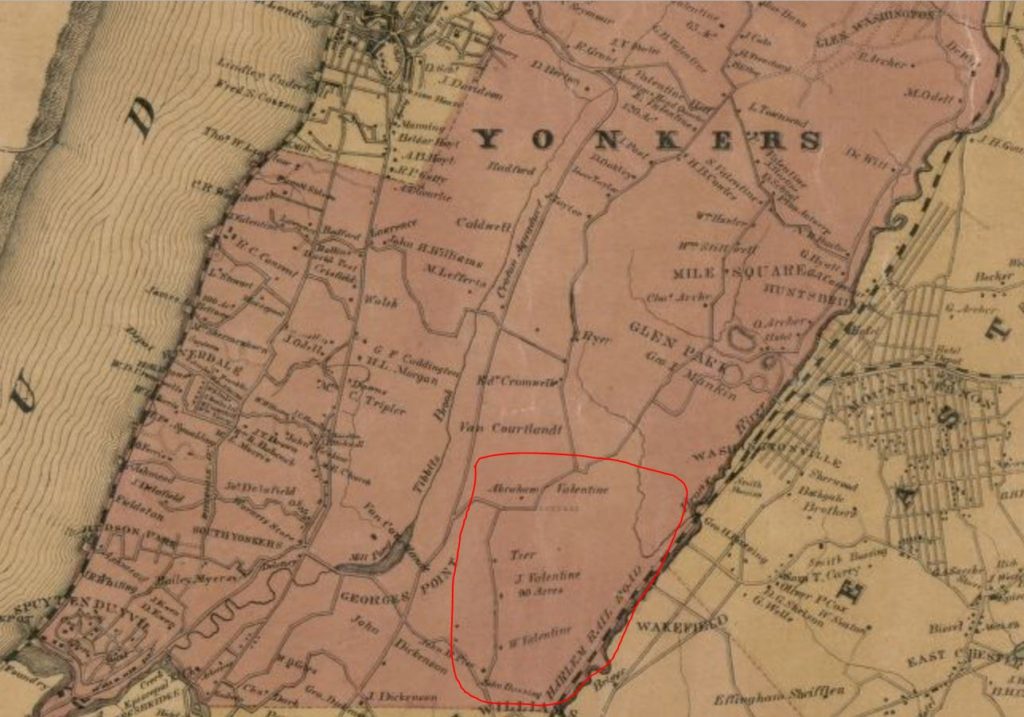

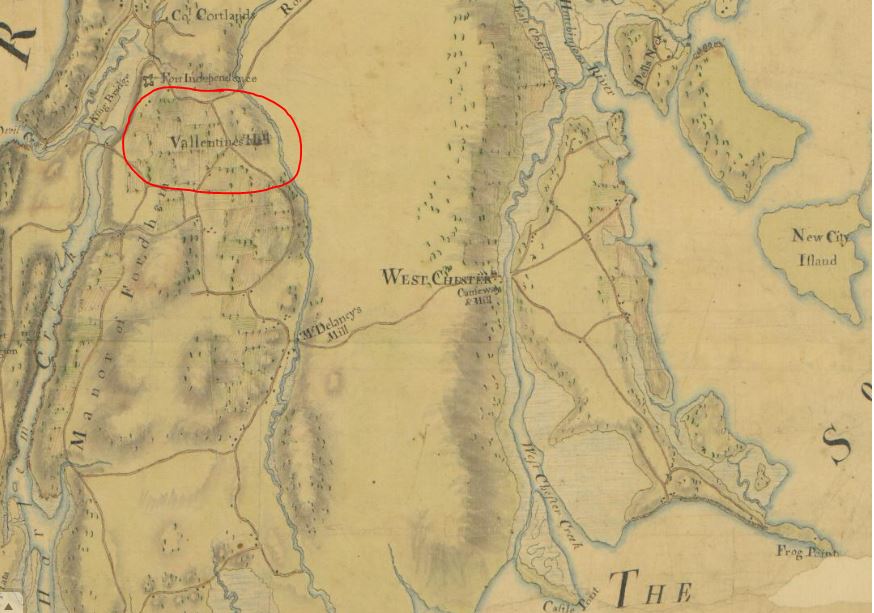

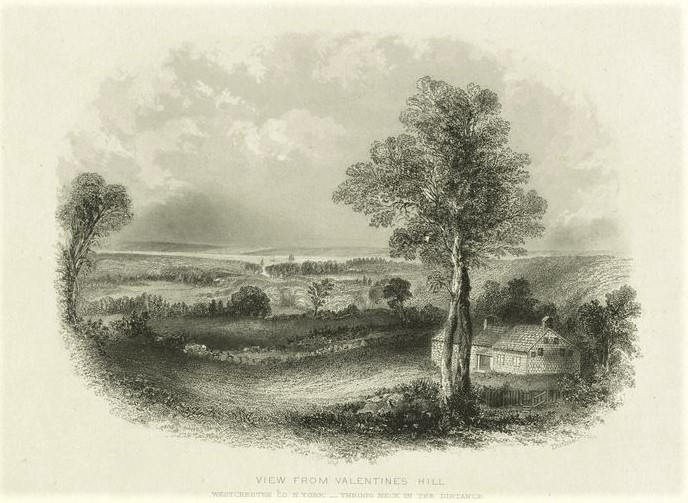

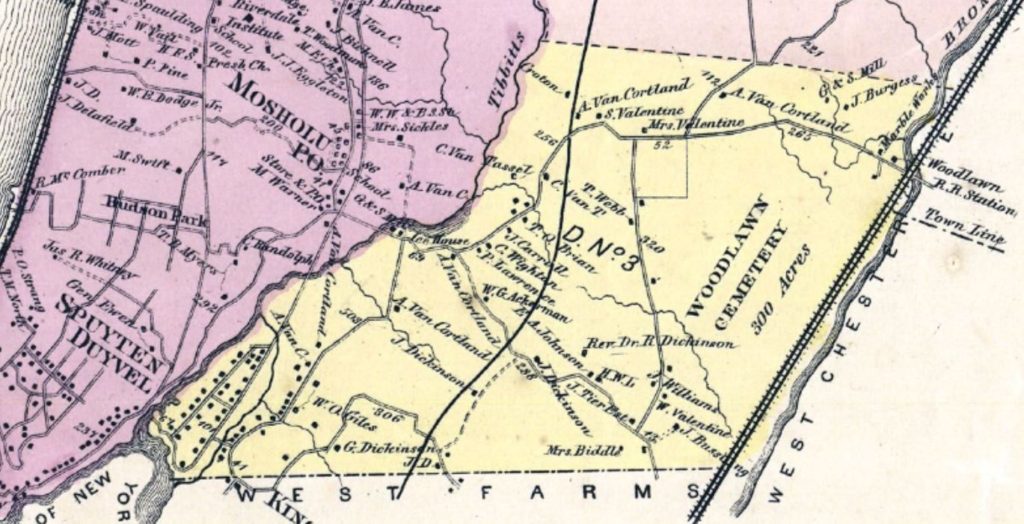

The new trustees explored the countryside north of the city for a desirable location for their proposed Woodlawn Cemetery. They found the perfect spot on an elevated ridge called Fordham Ridge, at the northern tip of the old Isaac Valentine’s Hill, in what was then part of the Town of Yonkers in Westchester County.

The initial site they chose was formerly the lands of British loyalist James De Lancey, who later sold his property to British loyalist Gilbert Valentine (1748-1819). It comprised about 313 acres, including cleared farmland and about 80 wooded acres. In 1863, the selected and surrounding property was occupied by the farms of Abraham Valentine, John Bussing, Jr., Daniel Tier, John Valentine, William Valentine, and others.

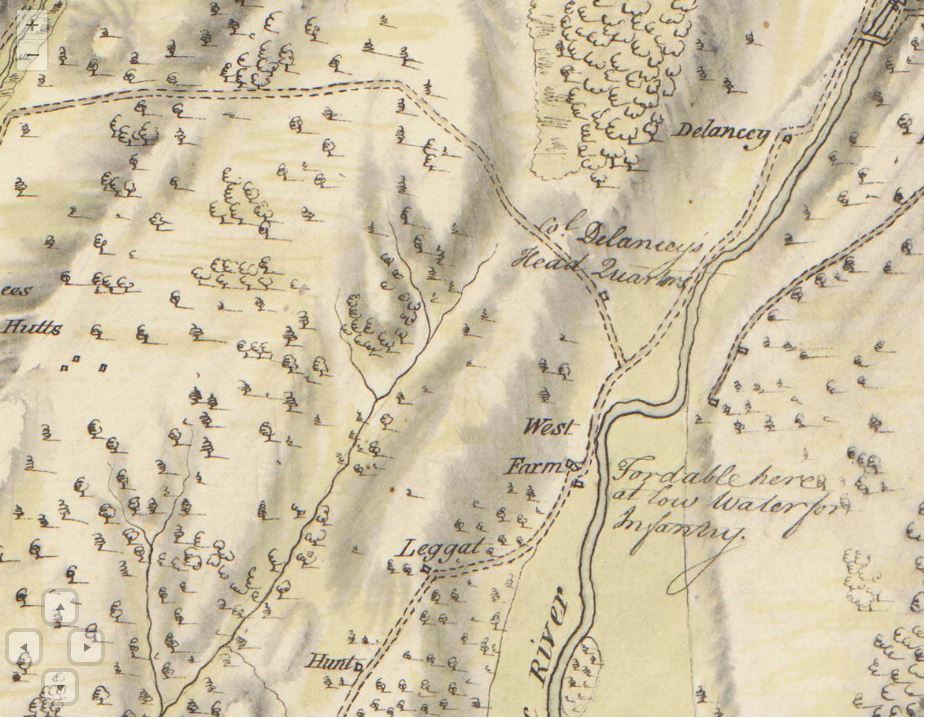

General Sir Henry Clinton, the future site of Woodlawn Cemetery is occupied by

Colonel De Lancey’s headquarters and his other property along the Bronx River.

William L. Clements Library Image Bank

The area of Valentine’s Hill and Fordham Ridge had played a prominent role during the Revolutionary War in 1776; several British redoubts were located on the ridge, including a small earthen fortification on a hill near the two-story stone house of Isaac Valentine, a blacksmith and farmer. This small redoubt, called Negro Fort, was just southwest of the proposed cemetery (where Van Cortlandt Avenue East and the Grand Concourse cross today, atop the hill at St. George’s Crescent).

William L. Clements Library Image Bank.

An Act Authorizing the Incorporation of Rural Cemetery Associations

Under Chapter 2 of the Laws of 1853, each trustee was able to acquire a portion of the acreage at his own expense, and then convey his new land to the Woodlawn Cemetery Association for a nominal fee. In exchange, the law allowed the trustees to receive half of all proceeds of the sale of all plots, graves, etc. made from such lands. According to an article in the Mount Vernon Chronicle on April 27, 1883, it was estimated that for an initial investment of about $200,000, the trustees could ultimately receive a $7 million return in plot and grave sales.

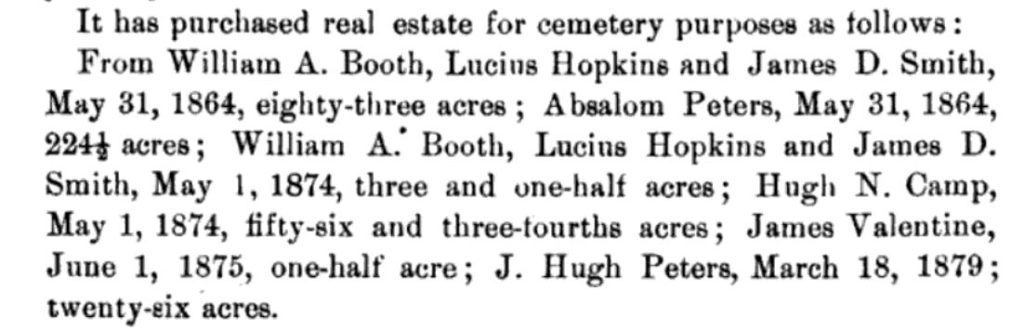

According to documents of the Senate of the State of New York, the trustees sold the following acreage to the Woodlawn Cemetery from 1864 to 1879:

Absalom Peters’ contribution included about 91 acres east of the railroad and north of the lands of Daniel Tier, which Peters purchased from Gilbert, Eliza, and John Valentine on March 12, 1864, for $20,500. He also conveyed about 120 acres that had formerly belonged to John De Lancey, and later, Gilbert Valentine and his son, Abraham (1773-1858). Peters purchased this land for $44,000 on March 28, 1864, from Daniel and Susan Tier, Euphemia Tier, Angeline Bohde, and Adella Bruner.

On May 31, 1864, Peters and his wife Harriet Hinckley Hatch Peters sold all of this property to the Woodlawn Cemetery for $66,942.50.

In addition to the lands acquired and conveyed by the trustees, the cemetery also purchased two additional acres for $10,700 from George Opdyke and Henry J. Dierring. This land was set aside for stables, barnyards, etc. for the cemetery’s cattle and horses.

During the remainder of 1864, the group enclosed 60 acres with a white picket fence; placed iron gates at each entrance; and erected a receiving vault on the site of the old Samuel Valentine farmhouse, near the northeast corner of the cemetery (East 233rd Street and Webster Avenue). The Harlem Railroad also agreed to build a new Woodlawn station near the northeast entrance.

The first interment–Mrs. Phoebe E. Underhill–took place in January 1865, just three months before the Civil War came to an end.

No Dogs Allowed at Woodlawn Cemetery!

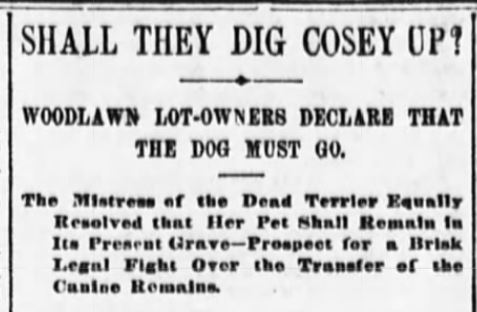

Fast-forward 23 years to 1888 again. Shortly after Cozey died, all hell broke loose. Many plot owners were adamantly against the presence of the dead terrier in the cemetery. Newspapers across the country–and even as far as Australia–reported on the public outcry.

For example, on August 23, 1888, the Catholic Union and Times (Buffalo, NY) published a scathing story about Mrs. Bell: “One of the most disgusting incidents of the present year was the recent ‘funeral’ of a wretched Skye terrier owned by a person—she can hardly be called a lady and certainly not a woman—named Mrs. Mary A. Bell.”

The article went on to describe the dog’s casket and burial at Woodlawn Cemetery in detail, followed by the following harsh words:

“And this is in Christian land, where thousands of poor, little children go daily without bread; where countless helpless orphans are crushed down under the pangs of poverty, yea and of starvation; where helpless mothers toil without ceasing from dawn until night, to win the few cents necessary to buy the food wherewith to fill the mouths of their babes.

Mrs. Bell should be ashamed of such a vile exhibition of heartlessness!… would it not have been more Christianlike to have lavished all that affection, if such it can be called, upon some poor little stranded waif of humanity? Would it not have counted more with her at the latter day to pass her eternity in the light of such an action than to herd with the mangy bones of her wretched terrier?

Mrs. Bell was disgusting, but the authorities of Woodlawn were contemptible to permit such a beastly and offensive spectacle.”

Word got out to Woodlawn Cemetery Association President William A. Booth and Vice President Kaleb B. Knevals, who had both been out of town when the funeral took place. On September 5, 1888, Knevals took the train to Woodlawn, where he met Mrs. Bell and ordered her to have Cozey’s casket dug up and removed to a more appropriate place for a canine.

According to an article in The New York Sun on September 4, Knevals told the press that had he or Booth been in town, the dog would not have been buried there. He also said if Mrs. Bell didn’t cooperate, they would disinter the dog and bury her in the cemetery barnyard. The officers of the association agreed to meet the following week to pass a resolution specifying that only human bodies could be buried in the cemetery.

I don’t know what happened to Cozey, but I do know he was buried in private somewhere else. I also don’t know if Mrs. Bell placed her husband’s body in the plot vacated by the canine. One of these days I’m going to visit the cemetery and roam about the Sylvan Dell Plot to see what I can find.

I’m also going to go out on a limb here and suggest that since all the land occupied by the cemetery had once been farmland, the remains of more than a few four-legged creatures are spending an eternity with the humans buried at Woodlawn Cemetery.

This article says Fannie was a “nondescript canine,” wioth a link to another articler callign her a “pure-bred Pug.” ????

I think what I meant to say was “nondescript color” — I will fix this. Thank you.