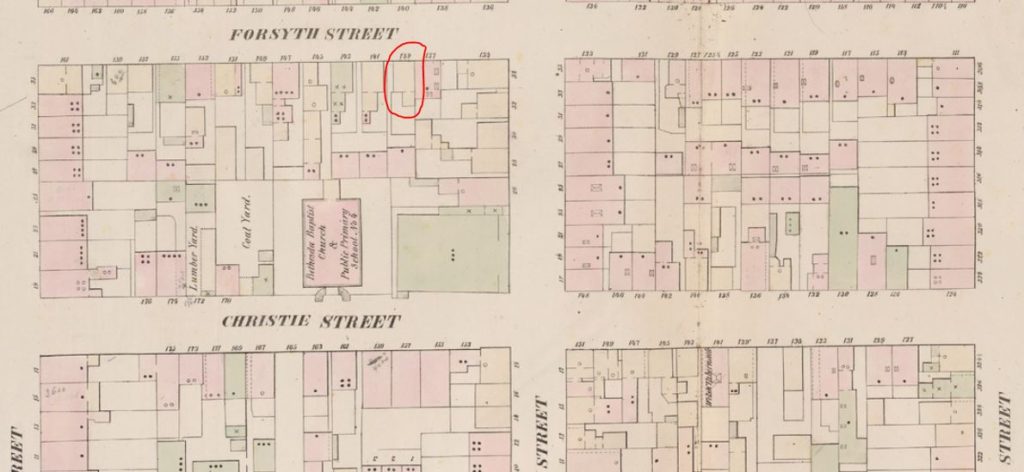

The night before the police had to break down the door to his room at 139 Forsysth Street and shoo about two dozen cats off his bed, 63-year-old Adolph F. Armreid said to his landlord, “I think I am going to die tonight.”

A few hours after the police chased the cats away, the neighbors began spreading rumors that the felines had been eating the flesh of the dead man when the police arrived. The rumors spread faster than a funny cat video goes viral on the Internet today.

The New York Times ran with the story. The New York Sun and the Evening Telegram sent a reporter to interview the landlord of 139 Forsyth Street, who told a very different story.

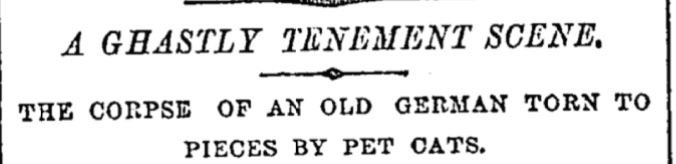

Version 1: The Cats Devour Their Master

On July 17, 1879, The New York Times reported that the body of an old German bachelor–whom they named Ferdinand Armreid–was found lying on the floor “much decomposed and covered with great holes, which the cats had eaten out, having evidently lived upon the remains for many hours.” The paper also said that when the police arrived, a tenant started shouting, “Old Bachelor Armried is layin’ dead in his room and his 20 cats was eatin’ his body all up!”

According to the Times, the cats “had kept up a dismal and diabolical howling all through the night and morning,” which sent tenant August Scheslau to Armreid’s room to complain. When the man didn’t respond to Scheslau’s rapping at the door, Scheslau opened the transom window and peeked into the room. That’s when he screamed for the police.

When the police arrived, they watched in horror as the cats ate at the man’s flesh. They determined that Armreid had been dead for more than 24 hours, and that the cats had turned to their master’s corpse when left alone with nothing else to eat.

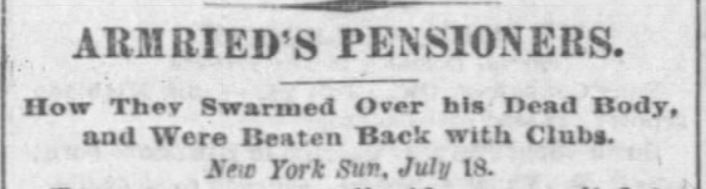

Version 2: The Cats Did No Such Thing

On the very same day, in a later news edition, the New York Evening Telegram wrote, “Diligent inquiry this morning resulted in finding that these stories were wild flights of the imagination of the gossips of the neighborhood.”

The following day, an article in The Sun explained that while Armreid’s apartment was “literally swarming with cats,” only two of the largest cats on his bed were licking his face, and his body was not injured at all.

The Crazy German Cat Man of Forsyth Street

According to official state documents, Adolph Ferdinand Armreid was born in Germany around 1816. He never married, and he lived alone in a small back-room apartment behind a lager beer saloon on the first floor of 139 Forsyth Street.

Armreid was a peddler who specialized in teas, which, according to the Chicago Tribune, he mixed skillfully and sold to druggists. He didn’t socialize with his neighbors, who thought he was rather eccentric.

According to the Tribune, Armreid had approached Scheslau a few years earlier when he was in search of lodgings (Scheslau was not a tenant, as the Times had reported, but the landlord for the building and the proprietor of the lager beer salon). He told the proprietor that his name was Henri.

Armreid was reportedly a good tenant. He always paid his rent on time every week, and he kept his room “tolerably tidy.” If he had any relatives at all, they never came to visit him.

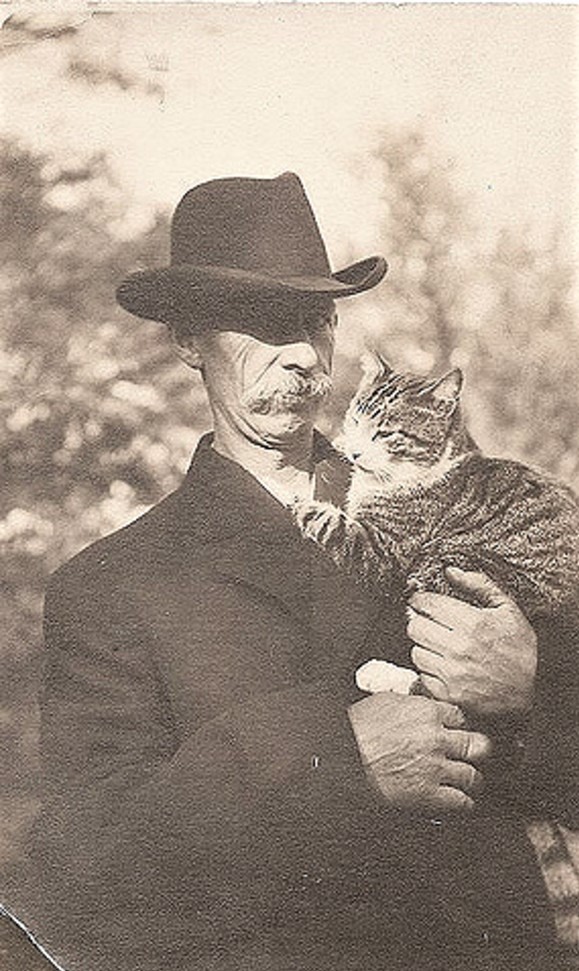

Armreid’s only “objectionable feature”–as reported in the Tribune–was his “extraordinary and unaccountable love for cats.”

According to several news articles, more than two dozen cats depended on Armreid. They crawled through the window into his room every morning for their daily meal, which he never failed to have ready for them. (Scheslau said it cost Armreid more to feed his cats than to feed himself.) Every morning, from two to three quarts of milk that were left at his door were devoted to the cats.

In an article that appeared in The Sun about a week after Armreid’s death, it was reported that a German man had called at Scheslau’s saloon on Forsyth Street shortly after Armreid’s death. The man said the two had been good friends in Germany, where Armreid had accumulated a lot of money.

The unnamed friend said Armreid had fled during the German revolutionary movement of 1848, and that he took the bulk of his earnings with him to America. The man thought the money was in the trunks that the police had found in his room.

The friend explained that Armreid went as Henri Androp in Germany, and that he had adopted the name of Armreid when he came to America.

According to the man, Armreid had collected his cats from all parts of the neighborhood, and he spent two years bringing them together and teaching them various tricks. They were so familiar with him that all he had to do was call and they’d come running. (Well, my cats come running to me also whenever food is involved.)

Mrs. Scheslau said at meal times the cats would all enter through the window and sit on the floor. He had a name for each one: Joel, Fritz, Faust, etc. Each animal knew his name, and as he called it, the cat would come forward and eat his portion of food.

The Cat Man’s Final Night

According to the Chicago Tribune, the first two weeks of July had taken a toll on Armreid, and he was struggling with the heat. He insisted on doing his work peddling his teas as usual, but he grew very weak, and was reportedly faint when he returned home at night.

On Tuesday night, July 15, Armreid went into the saloon and asked Scheslau for a piece of ice. As he walked away, he said, “I think I am going to die tonight.” The landlord tried to joke with him, but he just shook his head and went into his room and locked the door. He never opened the door again.

The next morning, after realizing the peddler had not risen and gone to work, Scheslau went to the door and knocked. When he called Armreid’s name, the only response he got was the hissing and mewing of cats that had assembled for their morning meal.

Scheslau went to the Eldridge Street Police Station, and officers Muller, Brady, and Cullen were sent to the five-story brick tenement building. Upon bursting the door open, they found Armreid’s body on the bed. There were numerous cats on the bed, including the two large cats that were licking his face.

The officers tried to clear the room of the cats, but the feral felines started clawing and biting fiercely. The men retreated and went back to the station to get further instructions on how to handle the situation. They were ordered to take their night clubs and drive the cats out of the room, taking care not to get scratched or bitten.

According to news reports, the officers were able to chase most of the cats out of the room, but a few of the more “ferocious and stubborn” cats hid under the bed and avoided all efforts to get them out. (This is what my stubborn cat Misha does every morning when I try to get her out of my room before I leave for work.)

It was surmised that Armreid’s body would end up in Potter’s Field, as no relatives came to claim it. What was to become of the cats was alarming to the residents. As one reporter noted, “If they are not taken away by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, there may be a lively serenade expected tonight.”

A Brief History of Forsyth Street

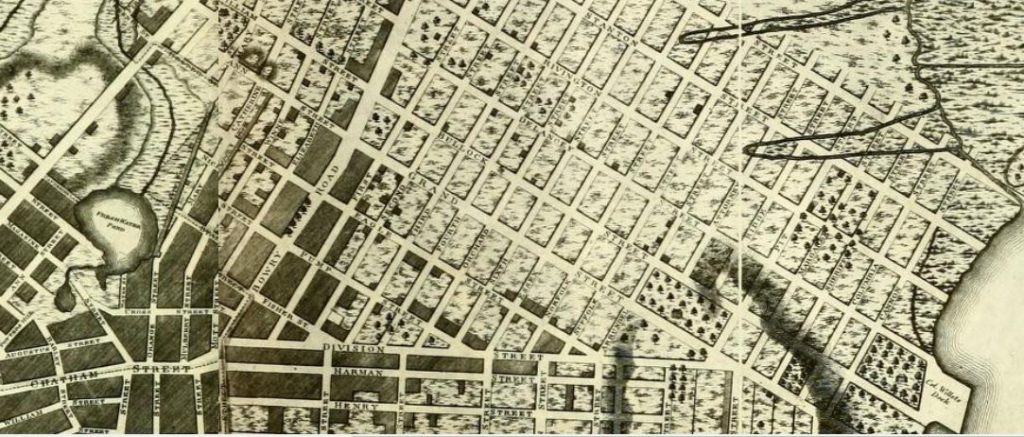

The tenement house where Armreid lived and died was on Forsyth Street, which was one of several streets that were once part of the 339-acre Delancey estate. This land, bounded by Rivington Street, the Bowery, Division Street, and the East River, dates back to about 1685, when Stephen de Lancey came to New York to escape the danger facing the Huguenots in France.

Stephen married into the van Cortlandt family and established his homestead at 54 Pearl Street, on land given to his wife by her father as a wedding gift. This home was later converted by Samuel Fraunces into the Queen Charlotte Tavern; a reproduction of this tavern still stands today as the Fraunces Tavern.

The Delancey family, led by Stephen’s grandson James, began “gridding out” streets in the southwestern part of their property on the Lower East Side in the 1760s. Their grid plan included a spacious square bounded by the present Eldridge, Essex, Hester and Broome Streets. They leased these parcels to poor artisans and craftsmen, and to wealthy investors who sub-leased the land to others.

During the American Revolution, the Delancey family actively supported the British cause. When the war ended, the state confiscated their land and they were forced into exile to Canada.

The State Commissioners of Forfeiture continued the grid pattern but eliminated the grand square. Little by little, the old frame buildings that were once home to the artisans and craftsmen were torn down and replaced with walk-up tenement apartments.

in 1817, three of the streets on the western edge of the former square were renamed for heroes of the War of 1812: First, Second, and Third Streets became Chrystie, Forsyth, and Eldridge Streets, respectively. The streets on the eastern side of the old square retained their original names: Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk—all English counties.

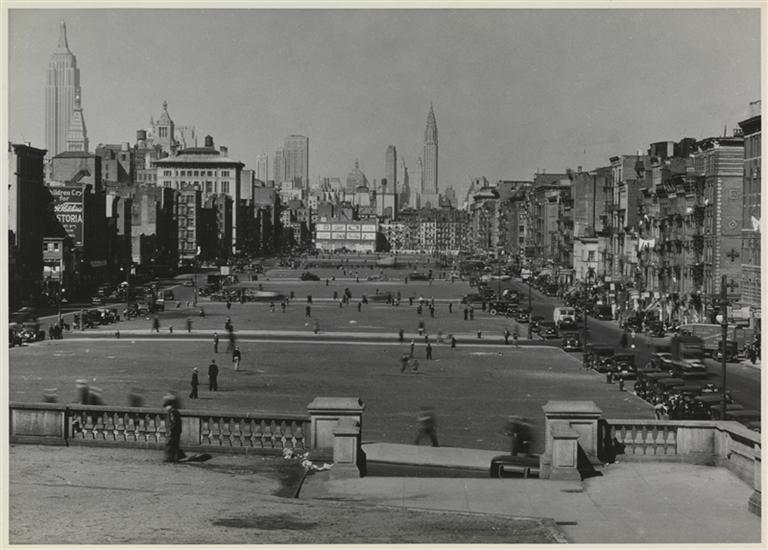

In 1929, the city acquired the land along Chrystie and Forsyth Streets from Canal to East Houston for the purpose of widening the streets and building low-cost housing. Instead, the old tenements, including Armreid’s tenement building at 139 Forsythe Street, were torn day to make room for parkland. The new park was named the Sara Delano Roosevelt Park–despite her written objection.

Forsyth Street at the northwest corner of Rivington Street, with the rear of the buildings on the east side of Chrystie Street, during demolition in 1930. New York Public Library Digital Collections.