There are some cats on Broome Street. American cats. English. Irish. Lithuanian German. Italian and Bohemian cats. They all materialize on this street. Every type and grade of feline society is represented here–from the famous Dutch mouser Tom to the indecent, dependent, despised tramp cat of unknown nationality. Fat cats, thin cats, black cats, white cats, dirty cats and very dirty cats, unhappy cats and very unhappy cats, conceited, comfortable-looking cats, and unfortunate homeless cats who are compelled either to subsist on charity or upon their own nocturnal prowlings.”–New York World, February 25, 1894

Miss Clementine Anderson and Miss Mary J. Anderson were two wealthy, educated, and refined “spinsters” who turned the neighborhood around Broome and Pitt Streets on the Lower East Side into a paradise for cats. As the reporter for The World noted, it was only those felines who lived far from 128 Broome Street (aka 22 Pitt Street) that were thin and unhappy.

The Anderson sisters lived with their brother, Andrew J., and his wife, Matilda, in a private residence on the northeast corner of Broome and Pitt Streets. The Andersons had one daughter, Isola J. Anderson, who died in 1872 when she was only eight years old.

Andrew made a living as a carman (a driver of horse-drawn vehicles or trolley cars). His two younger sisters stayed at home and never married. However, according to news reports, the sisters may have earned some money by renting furnished rooms in the home to various clubs, including the Pelham Social Club and the Oregon Wheelmen.

Although the sisters–both in their 40s–had money and owned property in “aristocratic localities,” they chose to remain in their childhood home in what was called Poverty Hollow on the Lower East Side. If it was good enough for their parents to live and die in, it was good enough for them.

The cats of the Lower East Side certainly knew a good thing when they saw it, too. Here’s how a reporter for The World described the scene:

Should the reader chance to stroll along Broome Street at night, when the noise of trade and traffic, the clamor of hammers in Hoe’s foundry, the shouts of drivers and the shrill notes of whistles are hushed–when the streets are quiet and deserted–should he then noiselessly pick his way along until he stood in front of No. 128 he would witness a sight not soon to be forgotten.

Under the wagons, on the fence, and on the sidewalk would he find cats, cats, cats! Cats everywhere in the vicinity of that number. No noisy quarrelsome crowd, but a peaceful, expectant, comfortable-looking collection of felines, all waiting for the never-failing supply of substantial food, cooked and prepared expressly for them, twice a day by their enthusiastic friends, the 128ers.”

According to The World, every morning the milkman delivered 10 bottles of milk to the Anderson sisters. They would boil it and serve it to the cats for breakfast. At night, the sisters would dole out “a goodly amount of meat, appropriately cut, served under the wagons.”

Occasionally, a greedy Tom or Tabby that was fortunate enough to have a home and enough food to eat would make his or her way to the mecca for homeless mousers. The sisters could spot the spoiled kitties right away, and would give them a gentle tap with a whip to shoo them away. The greedy cat might growl or hiss, but eventually it would slink away, never to return.

The End of the Cat Mecca

I do not know how much longer the cat mecca at Broome and Pitt Streets remained after the article about the Anderson sisters appeared in 1894. I have a feeling, though, that the cats were on their own within a year or two.

The construction of the Williamsburg Bridge between 1896 and 1903 resulted in drastic changes to the Lower East Side neighborhood. Developers also began buying older buildings in the area and replacing them with larger tenement buildings.

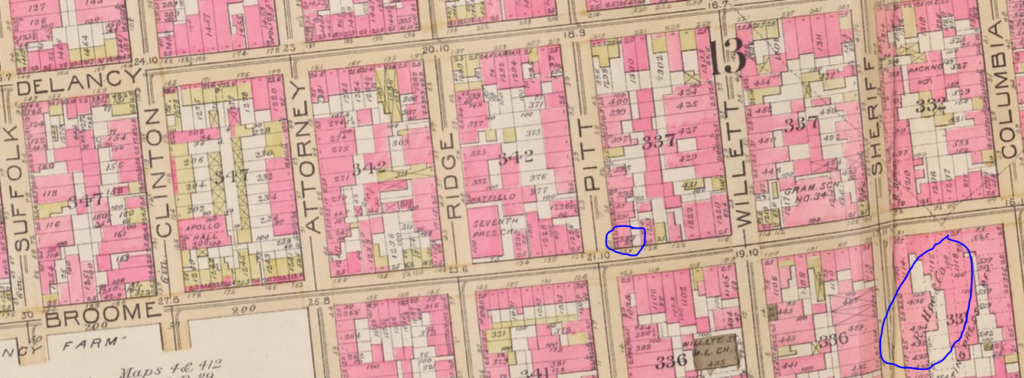

In 1897, developers purchased the old three-story buildings at 28 and 30 Pitt Street (perhaps the cottage double-house shown above?). By 1903, the former private residence at 128 Broome Street/22 Pitt Street had been replaced by a large, six-story tenement building pictured below.

A Brief History of Pitt Street: Poverty Hollow and Mount Pitt

During the late 1800s, the neighborhood where the Anderson cat ladies lived was known as the Oriental District. Within this district, and very specific to the intersection of Broome and Pitt Streets, was a neighborhood called Poverty Hollow, which comprised a section of the Thirteenth Ward north of Grand Street and east of Pitt Street.

The name of the neighborhood dates back to the early days of New York, when the hill on Pitt Street was called Mount Pitt (aka Jones Hill) and the bottom of the slope was the hollow. Then, the population was primarily Irish, with a few German and Jewish families scattered throughout. It was not uncommon to see a goat eating the grass on the side of Mount Pitt.

According to various maps, Mount Pitt was 40 feet above sea level at its highest point, which was at the intersection of present-day Grand and Ridge Streets. The elevation in the hollow at Broome and Pitt Streets was 22 feet.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, Poverty Hollow and other Lower East Side neighborhoods had their own mayors, so to speak, who looked after the welfare of the poor residents, bailed residents out of jail, and made sure the men were taking care of their wives and children. Several “commissioners” worked with the mayor and held titles such as Duke and Manager.

For 32 years, Pat Connelly was the esteemed mayor of Poverty Hollow. He held court in an old shanty on Delancey Street, where he lived and maintained a saloon.

In 1896, Connelly was ousted by Abe Sprung in a heated, politically backed contest. Sprung and his brother Max, the Duke of Willett Street, operated from Mark Hanna Schulum’s cigar store at the top of Mount Pitt.

Connelly regained power a few years later, but in 1901, he was booted from his shanty, which was in the line of the new Williamsburg Bridge.

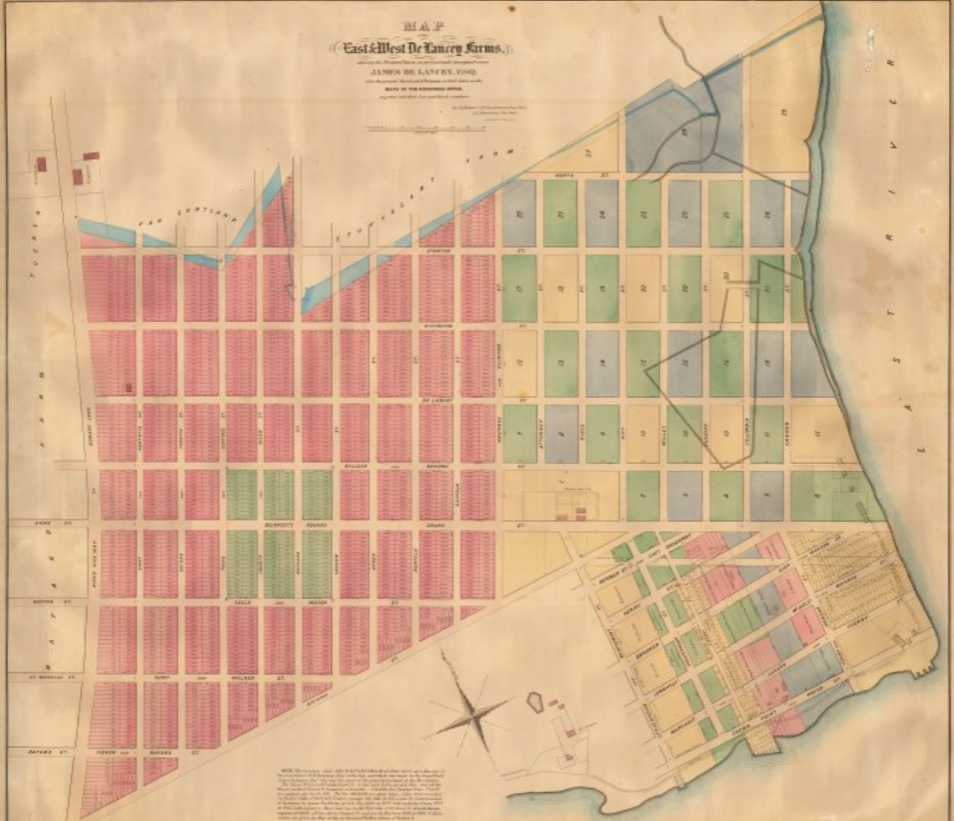

The De Lancey Farm and Mount Pitt, aka Jones Hill

The Andersons’ home at Broome and Pitt Streets was erected on the old DeLancey Farm, at the base of Mount Pitt (aka Jones Hill), as noted in the map below. When this map was created in 1865, the lots east of Clinton Street had not yet been laid out because the hill was not suitable for robust development.

The recorded history of this property goes back to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. In the 1600s, the Dutch West India Company created several large farms, or bouweries, that were granted to settlers. Two farms occupied this part the city: Bouwerie Number 5 (later of Cornelis Claes Swits) and the farm of Claes van Elslandt (1647).

In the early 1700s, the land within these Dutch farm grants was incorporated into the large farm of James DeLancey, the Lieutenant Governor of New York. Over the years, DeLancey also purchased land north of Division Street (now East Broadway), eventually accumulating much of what is now the Lower East Side.

Following the death of James DeLancey, Sr. in 1760, his son James DeLancey, Jr. inherited the farm. In 1763, he granted a two-acre parcel of land “adjoining to the road which leads from the Bowery Lane to Corlears Hook” to his sister, Amelia, and her new husband, Thomas Jones.

Jones, a provincial judge and military veteran, built a “large double house of wood” on the elevated site in 1765 and named his estate Mount Pitt in honor of William Pitt (later Lord Chatham), whom Jones greatly admired. The property, bounded by today’s Clinton, Broome, Pitt, and Grand Streets, was surrounded by gardens and a fine orchard, and offered commanding views in all directions.

During the Revolutionary War, Mount Pitt was the site of an American fort sometimes referred to as the “Crown Point Battery,” “Fort Pitt,” or “Jones Hill Fort.” The fort, described as a strong circular redoubt with 8 cannons, was later occupied by the British; many Hessians who fought for the British camped in this area during the war.

Throughout the Revolution, the DeLancey and Jones families remained loyal to the British crown. Under the Act of Confiscation of 1779, the DeLancey estate was divided and sold by Commissioners in Forfeiture Isaac Stoutenburgh and Philip Van Cortlandt.

Morgan Lewis purchased the Mount Pitt property in 1784 for 970 pounds (about $2,300 back then). He then sold the land to John R. Livingston (brother of Robert Livingston) in 1792.

Other parcels of the eastern portion of the DeLancey farm were sold to Joshua Ketcham, John R. Meyer, and John Quackenbos. The Anderson home at 22 Pitt Street was built on one of the Quackenbos lots.

The division of DeLancey’s farm and other large farms resulted in rapid street development and urbanization of the Lower East Side. However, due to the Mount Pitt estate, the area northeast of Clinton and Grand Streets was developed later than the surrounding neighborhood.

Livingston and his heirs reportedly did not begin to sell smaller lots within the property until the 1820s. For many years the home on Mount Pitt was occupied by several gentlemen as a private residence.

The Livingston home became a public house sometime around 1811, but it was never that popular. When the old Mount Pitt was leveled in the 1820s, so too was the estate.

In 1831, after its original church on Sherriff Street was burned down by the anti-Catholic Know Nothing party, St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church purchased a portion of the Livingston estate from the mayor of New York. The parish constructed its new church on Grand and Ridge Streets–the exact site of the former Livingston home–in 1832.

By the 1840s, nearly all the remaining lots in the neighborhood were developed with wood frame houses and stores. Most of these old buildings were replaced with four- and five-story brick tenements during the mid-19th-century immigration surge.

Incidentally, remnants Mount Pitt can still be viewed today: several churches in the Lower East Side, including the old Willett Street Methodist Episcopal Church (1826), were constructed of schist quarried from the leveling of the hill.

If you enjoyed this Lower East Side cat tale, you may enjoy reading about Fritz, Faust, and the Cat-Man Peddler of Forsyth Street or about Rosalie Goodman, the Crazy Cat Lady of the Lower East Side.