The following is a fun tale about Mike, the female Williamsburg Post Office cat. Not only was Mike misnamed, she was “missent.” If there had been an Internet back then, this story would have surely gone viral.

The Cat Is Out of the Bag

You’ve no doubt heard the term, “Letting the cat out of the bag.” In Old New York, it was more like getting the cat out of the bag. The mail bag, that is.

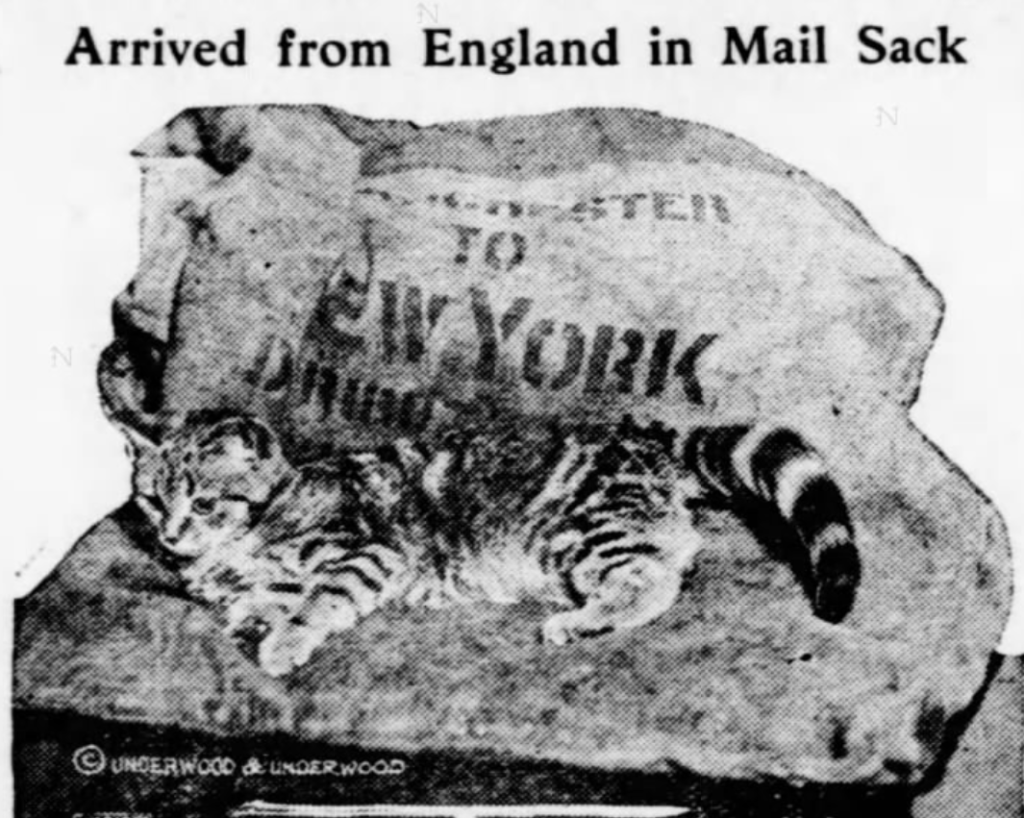

There was Eurita, a drug store cat who sprang from a mail pouch after being mailed to the Branch Post Office H on Lexington Avenue and 44th Street. And there was Kelly, the cat who sailed from England to New York sealed in a mail sack for eight days. I even wrote about a man who mailed a kitten to his niece in Yorkville by way of parcel post.

None of these cats, however, were post office cats. Sure, postal workers at the City Hall Post Office often sent kittens through the mail to other post offices in need of a few good mousers. But Mike was a post office cat who should have known better than to take a cat nap in a mail bag.

No one could tell the press where Mike came from, or why the mother of so many kittens should bear such a name. But she purred her way into the hearts of everyone working at the post office many years earlier. And so the “whole office was chopfallen” when she disappeared.

The story began on March 14, 1895, the day Mike disappeared from the Williamsburg Post Office (aka Station W) on the northwest corner of Bedford Avenue and South 5th Street. That day, a sack of newspapers destined for a foreign port arrived at the General Post Office in Manhattan. The origin of the mail bag was Station W.

As clerks began setting set aside a large pile of mail sacks for the next journey on a steamship, clerk A.J. Eamley heard some faint “meows” coming from somewhere in the room. Upon investigation, he discovered that the pathetic cries were coming from inside a large newspaper bag. When he opened the sack, a disheveled black and white cat jumped out.

Had this not been a federal post office, Eamley would have probably tossed the cat aside and went on with his work. But because it was illegal to send live cats through the mail, Eamley submitted a short and sweet official report to Postmaster Charles Willoughby Dayton: “I have to report that a live cat was forwarded to this office in a sack of newspapers under the accompanying label.”

Postmaster Dayton forwarded the report to Superintendent R.C. Jackson of the New York office, along with his own note stating, “Evidently this has been missent.” Superintendent Jackson responded, “What information can be furnished by your office regarding the missending of this cat?”

Postmaster Dayton forwarded the correspondence to the Williamsburg Post Office with a request that a report be submitted at the earliest possible moment. Meanwhile, as all these notes were passing back and forth, Mike feasted on the milk that the clerks provided for her and napped in a sunny spot on the mailroom floor.

When Station W Superintendent Francis A. Morris received the correspondence from Postmaster Dayton, he prepared the following report:

This inquiry relates to our office cat, a highly prized animal. She was of an inquiring turn of mind and happened to be in the foreign paper sack at the time of dispatch. Clerk Taylor did not know of her presence there and tied up and forwarded the sack to your office. We will very cheerfully pay all expenses incurred by the present custodians for board, maintenance, etc., if they will return her in good condition to this office.”

Postmaster Dayton sent Morris’s report to Superintendent Jackson, who in turn sent the following communication to Dayton:

To Postmaster Dayton, inviting attention to the information furnished by the postmaster at Brooklyn, N.Y.–Can the request of the superintendent of Branch W be complied with?

Postmaster Dayton replied:

In accordance with the request of the superintendent of Branch W (Brooklyn), I have to inform you that the cat has been returned by special messenger free of all charges.”

The following day, Superintendent Morris sent a note to Superintendent Jackson:

The cat came back in an improved condition. Please convey to the honorable postmaster of New York, N.Y. my most sincere thanks for the courtesy shown this office.”

Upon Mike’s return to the Williamsburg Post Office, Superintendent Morris issued an order that extra care be taken to see that the cat was not accidentally shipped abroad. Mike didn’t have much to say about her adventure (although she may have warned her kittens about the dangers of mail bags), but the clerks said she appeared to be more careful about taking naps in mail pouches.

This concludes the story of Mike the cat. If you are interested in learning more about the history of Williamsburg and its postal services, the next section is for you.

History of the Williamsburg Post Office

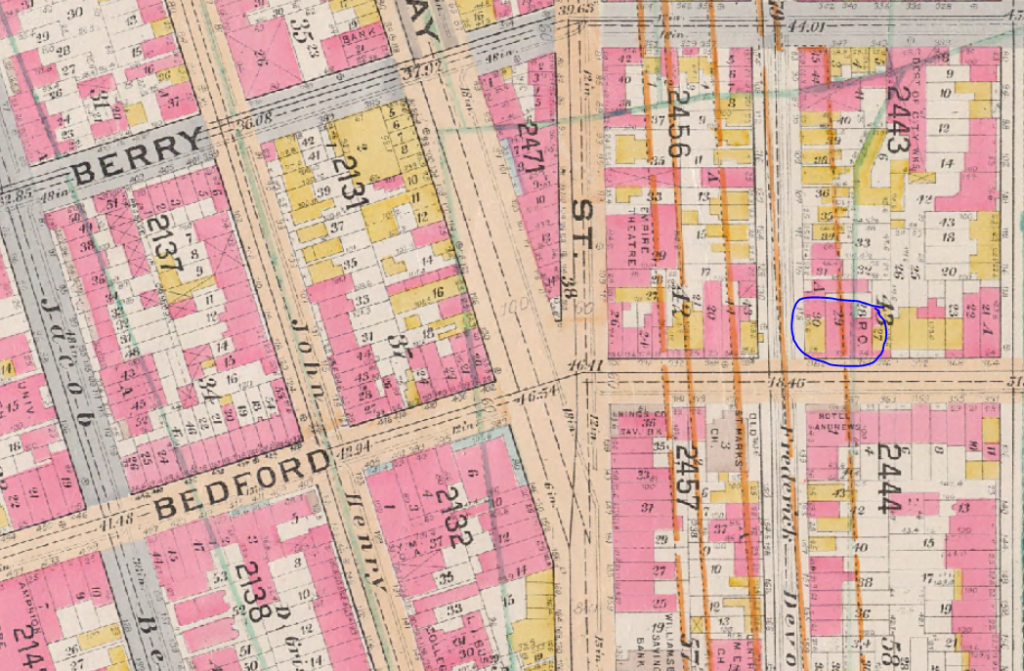

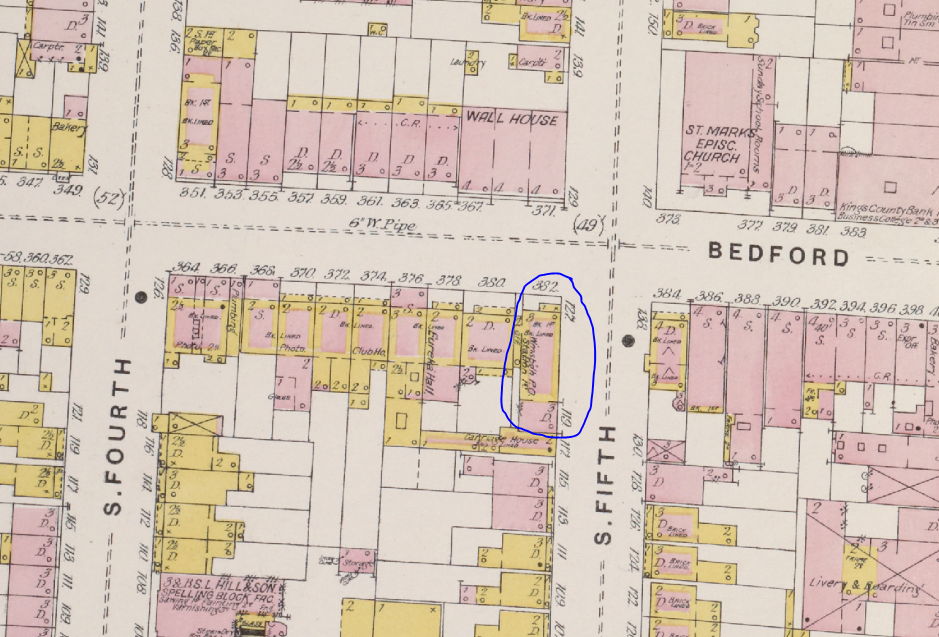

When Mike was serving as a post office cat, the Williamsburg branch post office was in its fourth location, occupying a large, one-story domed building at 378-380 Bedford Avenue. The building also had an annex with an entrance on South 5th Street.

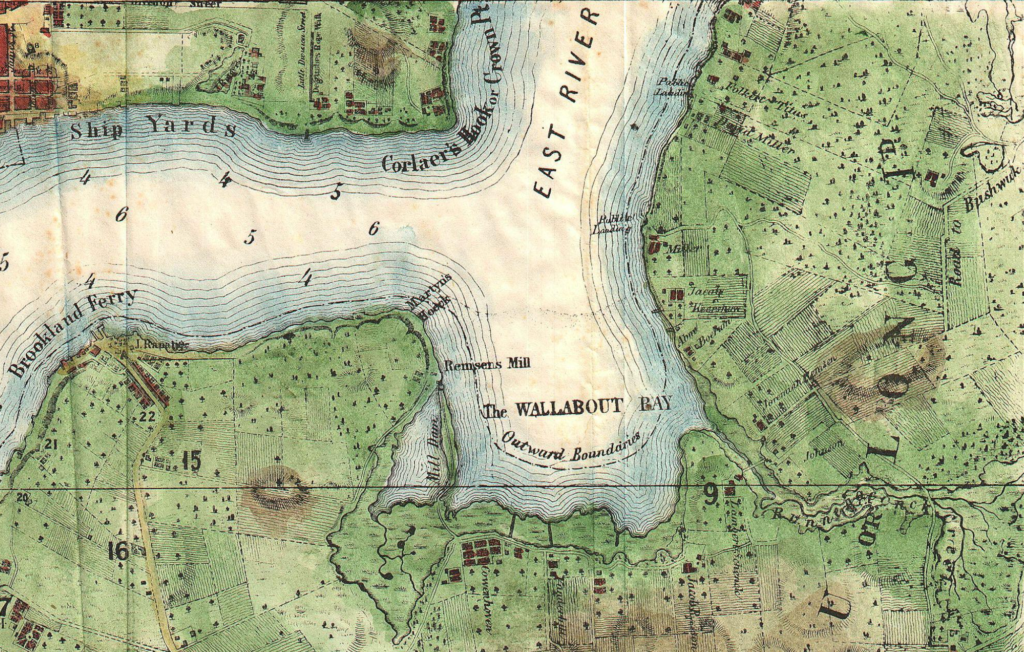

In the 17th century, this part of Williamsburg was known as the Keike or Lookout, in reference to a high point of land along the East River from the Wallabout Bay north to present-day North 4th Street. One of the first settlers on this land was a ship carpenter named Lambert Huybertsen Moll, who had purchased some land from Cornelis Jacobsen Stille.

Moll received a land grant for the triangular tract from the West India Company on September 7, 1641. The West India Company had purchased the land from the natives in 1638.

When Moll moved to Esopus, New York, in about 1663, the land became the property of Jacobus Kip (of today’s Kip’s Bay in Manhattan). Over the years, the land was split up into north and south sections and passed from Kip’s estate to James Bobin, Abraham Kershow, Jean Meserole, David Moleanaer (Miller), and Frederick Devoe, among others. The Kershow and Miller farms on the east shore of the Wallabout Bay are noted on the 1767 map below.

In 1828, Devoe had his property of about 12 acres extending from the river to 7th Street (now Havemeyer Street) and along South 5th and South 6th Streets surveyed into village lots and mapped. It was on this land that Mike the cat made her home in the 1890s.

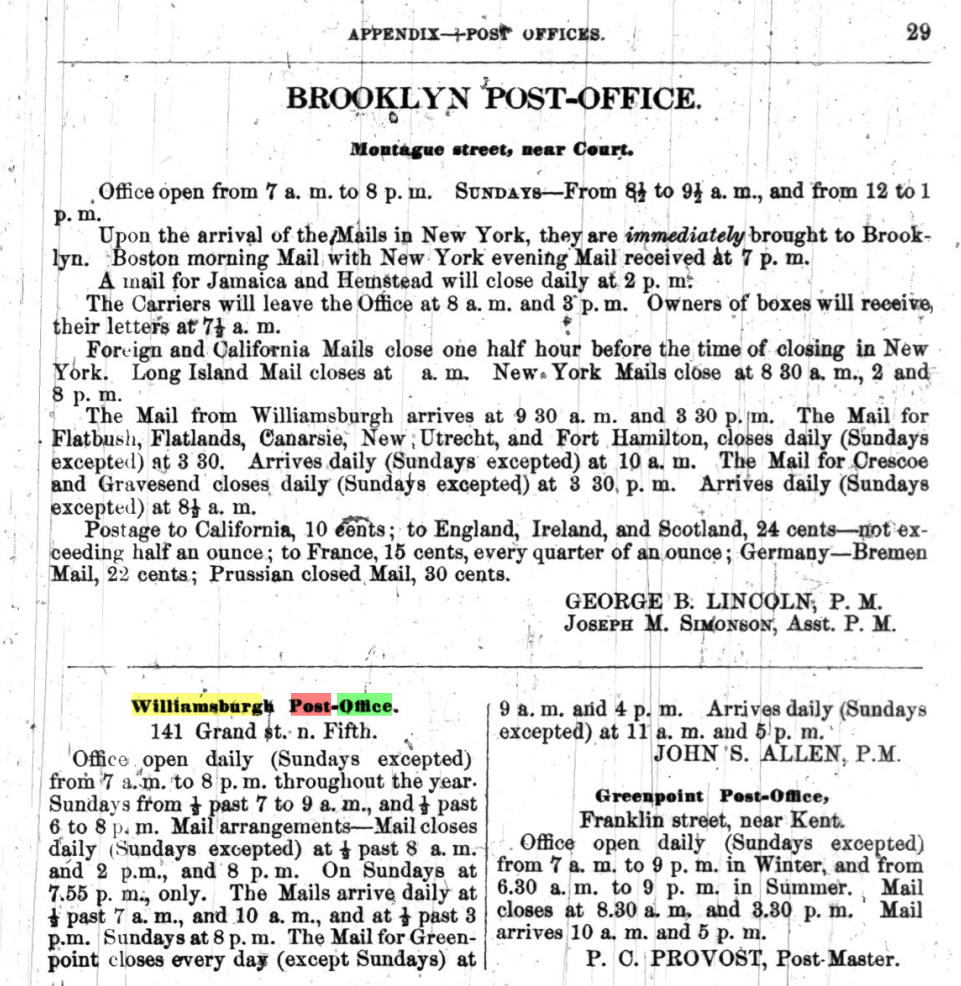

The origins of postal services in Williamsburg date to the mid-1800s, when there were only 3 post offices in all of Brooklyn, including a branch at Greenpoint and the General Post Office that served all the other neighborhoods.

The Brooklyn post offices did not occupy government-owned buildings at this time, but rather leased space in storefronts, hotels, and other places of business. In the 1840s, the Williamsburg post office was located in the drug store of Chauncy L. Cooke on First Street (Kent Avenue) between Grand and N. 1st Street. This post office served the Eastern District, which included Williamsburg, Bushwick, and North Brooklyn.

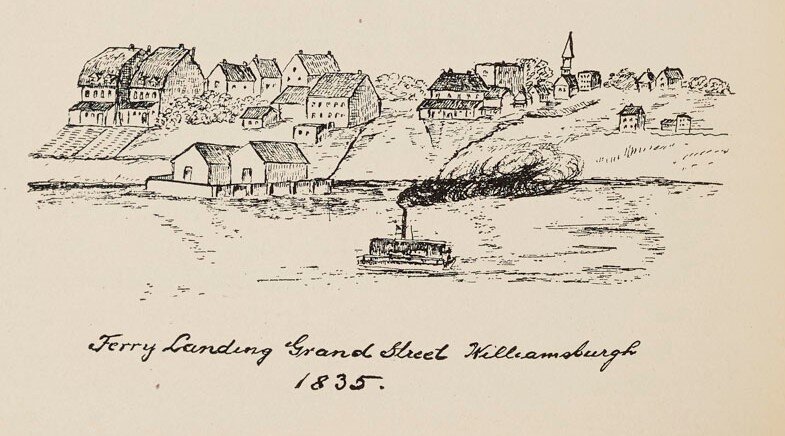

In the 1850s, the post office was centrally located at what was then 141 Grand Street, between Fourth and Fifth Streets (present-day Bedford and Driggs Avenues). Back when the district extended only from Bushwick Creek to Broadway, Grand Street was a significant central street. All the principal stores were on this street, and the ferry station at the foot of Grand Street created much foot traffic comprising residents and travelers alike.

As the district extended to Flushing Avenue (South Williamsburg), Grand Street was no longer considered a central location. Now the majority of the people in the district were travelling down South 7th Street (which merged into Broadway in 1860) to take the ferries to Peck Slip, Manhattan. Husted and Kendall’s stage ran every half hour from the ferry along Broadway to the Franklin Hotel at the corner of Broadway and Myrtle Avenue.

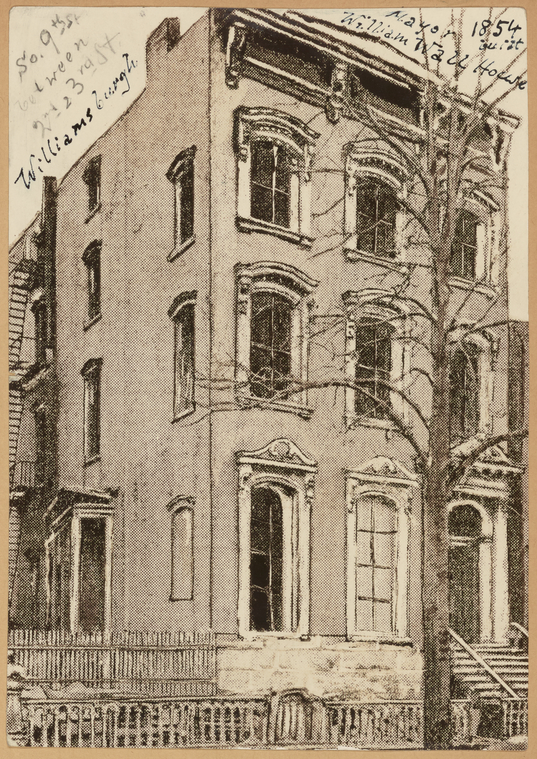

One prominent resident who recognized this shift was William Wall (1800-1872), the second and last Mayor of the City of Williamsburgh and the owner of a rope walk at Bushwick Avenue and Marshall Street. Wall, who had served in Congress during the Civil War, realized that an executive hotel in the finest section of Williamsburg was necessary.

So in 1855 he founded the Wall House hotel on the northeast corner of Fourth Street (Bedford Avenue) and South 5th Street. The hotel, which was the first and only hotel in the Eastern District for many years, opened in May 1856.

The 75×50-foot, four-story with basement hotel featured 40 rooms, a large dining room, and a cafe. Many of the early guests were families who “did not care to encounter the cares of house-keeping.” The first proprietor was A.H. Bellows.

Sometime around 1862, plans were made to move the post office to a more central location. Government agents listened to all the objections of residents who were furious that the post office was moving “to an obscure corner of Williamsburgh,” but a decision had already been made.

A new Williamsburg Post Office (aka Station W) opened in the Wall House hotel in May 1862, under Postmaster John S. Allen. The post office occupied a small space, about the size of a small store, on the ground floor of the brownstone hotel.

The post office made another move in June 1874, this time across Fourth Street to the former home of Dr. Lucius Noyes Palmer on the northwest corner of S. 5th Street (later known as 382 Bedford Avenue). Dr. Palmer, a beloved physician, had lived in this home until about 1860, when he moved across the street to a frame house on the southwest corner, where he died in June 1885.

Under Postmaster Talbot, the 25×75-foot post office was refurbished with swinging doors and a plate-glass front, and featured black walnut fittings. Talbot surmised the new space would be more than adequate to meet the demands of the district for some time to come.

In 1874, the district had 20 mail carriers and 5 clerks. By 1892, there were 61 carriers and 16 clerks. The old Palmer house was too small to accommodate the post office.

In June 1892, under a contract with J. Culbert Palmer, workmen began tearing down the four old buildings owned by the Palmer estate, including those occupied by the post office, a book shop leased by D.S. Holmes, the Republican Club headquarters (known as Old Homestead Hall), and Eureka Hall. Three one-story buildings of "fancy stone" with domes and skylights were erected and rented to the Station W post office for $2,500 a year. It was about this time that Mike the cat moved in.

In 1899, the post office moved again when Palmer offered the Bedford Avenue building for use as a new library branch for the Eastern District. The Station W post office moved into a two-story brick and limestone building at 236 Broadway, just opposite the Williamsburg Bridge plaza. I don't know if Mike was still around, but the building does not look like it would have been welcoming to a cat and her kittens. During this time period, the old Wall House hotel changed hands a few times. For several years it was owned by Paul Wiedmann and known as the Hotel Boswyck. It was renovated in 1890 and leased to Frank B. and Fred G. Andrews, who took over as proprietors in July 1895 and renamed it the Hotel Andrews. But in 1896, construction began on a new East River bridge (Williamsburg Bridge). By 1901, all the buildings along S. 5th Street in this area, including the post office, Hotel Andrews, and St. Mark's Church, were being razed to make way for the approach to the new bridge.

In April 1928, under Postmaster Albert Firmin and Superintendent Edward Thompson, Station W moved for the last time (as of now) to 263 South 4th Street at Marcy Avenue. Neither of these buildings look like they'd make a good home for a cat like Mike and her kittens.