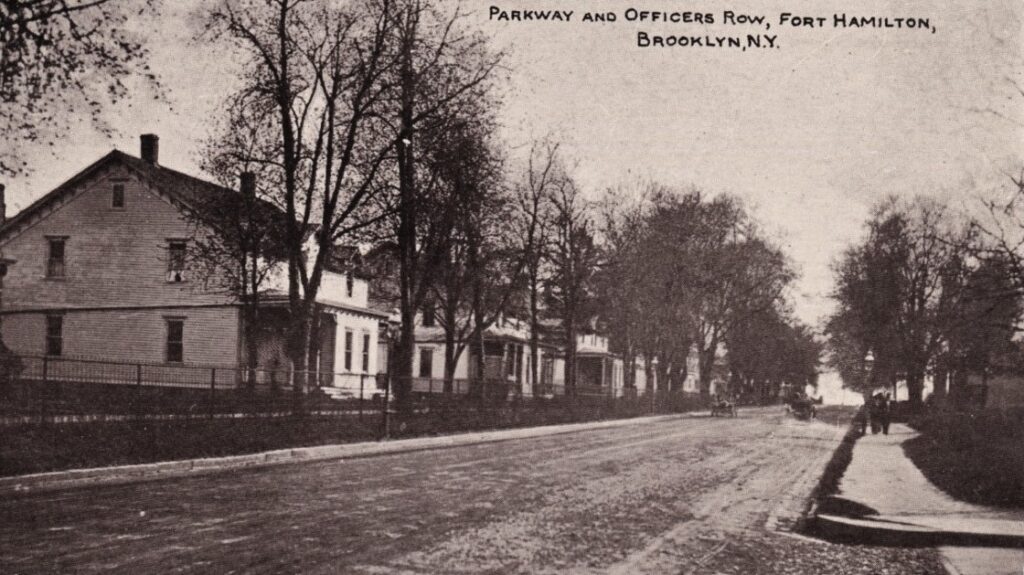

During World War II, the United States Army Garrison at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn was an important staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation.

At the start of America’s involvement in the war, more than 100 new structures sprang up within the fort limits, including temporary barracks, warehouses, a theater, service club, signal office, hospital buildings, and even a new fire station for the Fort Hamilton Fire Department.

The Fort Hamilton Fire Department, installed in December 1941, was one of many military installations within New York City that had a paid civilian fire department and fire apparatus during and after World War II, including Fort Jay on Governor’s Island, Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island, and Camp Rockaway in Queens.

These federal fire departments cooperated with the FDNY and operated at fires with FDNY units. Chief Gustav R. Moje, a former FDNY captain with Engine 88 in the Bronx who had retired in 1936 after 32 years of service (including several years as a lieutenant with Engine Company 8), took charge of organizing and overseeing the department.

The department started off with 10 city firemen who were on the FDNY appointment list, but for whom city funds had not yet been allotted. These men received a 6-month leave of absence to help organize the army post department, after which they returned to the FDNY. Following this period, Chief Moje was responsible for training enlisted men as firefighters.

By 1947, the Fort Hamilton Fire Department had a force of 27 enlisted men plus 4 civilian assistant and senior firefighters. The company also included a mascot dog named Butch.

Next to Chief Moje, Butch had the longest record of service with the department. He had showed up shivering and without a license outside the chief’s quarters on a frosty winter night shortly after the department was organized.

Described as a “waddling fox terrier” with a stumpy tail, Butch was a fighting fireman—albeit he didn’t fight fires, but rather other dogs on the post. “That’s why he hasn’t hardly any teeth left,” Assistant Chief Adolph Salvano told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “He’ll tackle any dog regardless of size.”

Fort Hamilton: Origin of the Bronx Cheer?

During his 6 years as head of the Fort Hamilton Fire Department, Chief Moje collected many anecdotes about the post. One such trivial anecdote involved the origins of the term “Bronx cheer,” which Merriam-Webster defines as a boo, catcall, hiss, hoot, jeer, or raspberry.

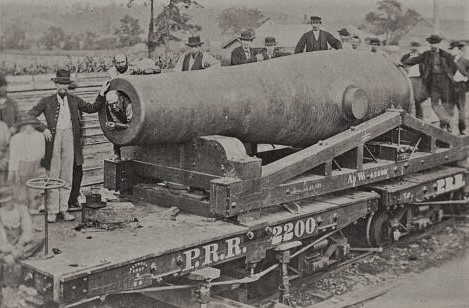

The story refers to a large cannon, the Rodman gun (named for ordinance pioneer Thomas Jackson Rodman), still standing outside the fort limits at Fort Hamilton Park, in John Paul Jones Park.

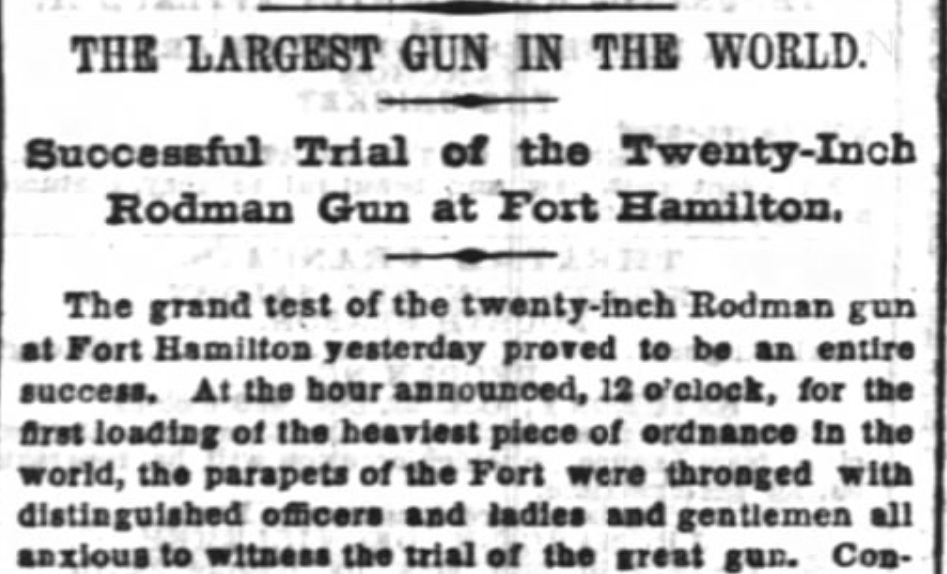

Once called “Old Big Mouth” and heralded as the biggest gun the world for its 20-inch bore, the mammoth cannon was constructed in 1864 at the Port Pitt foundry, Pittsburgh. Soon after its construction, it was mounted at Fort Hamilton overlooking the Narrows to protect New York Harbor.

The 20-caliber Rodman gun reportedly inspired author Jules Verne’s conception of a cannon that could shoot men into space in his book “From the Earth to the Moon” (1865).

On October 26, 1864, at the cannon’s first firing trial, the Department of Charities and Correction steamer Bronx cruised by with about 1,000 passengers aboard. The cannon’s first discharge was a blank cartridge fired by 100 pounds of power. The gun boomed, recoiled a bit, and that was it.

Expecting a much bigger noise, the Bronx passengers were quite disappointed. For its second trial firing, the men aimed the cannon—crammed with 50 pounds of powder and a solid iron ball weighing 1,800 pounds—toward Staten Island. The shot traveled a quarter of a mile, bounced a few times on the water, and sank.

The Bronx crowd booed and jeered at the unsatisfactory display. As a reporter for the New York Daily News concluded after sharing this tale of Old Big Mouth, history does not say if this incident was in fact the origins of the “Bronx cheer.” But it could be, and that, in fact, makes it a fun story to share.