There is a saying that goes, “Cats rule. Dogs drool.” When it came to picking a side during the women’s suffrage movement in Brooklyn, the cat in this story ruled. She picked the winning side–the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Association.

Pussy Suff was a black cat with seven toes on each forepaw and “a nasty, catty disposition.” According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, she was a cat that believed in women’s suffrage. The news reporter put it this way:

“Merrow, merrow, meeeerrrrooowwww!” Translation–“Votes, votes, votes for woman!!!”

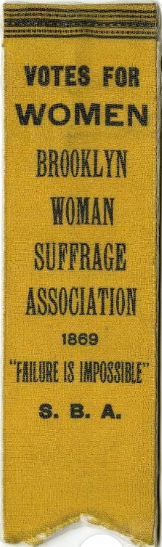

Perhaps the cat knew that the name of the woman who headed by Empire State Campaign Committee for the woman suffrage movement in New York State was Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt (the successor to Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who founded the National Woman’s Suffrage Association in 1869). But more likely, she joined the association because she was a good neighbor.

Pussy Suff lived next door to the first headquarters of the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Party at 27 Lafayette Avenue. She spent many hours at the headquarters and was on a “purring acquaintance” with many of the Brooklyn suffragists.

The cat had a fondness for the group’s yellow ribbons, and would often steal one of two and carry them off. The women decided to give her a ribbon to wear around her neck, which she did so with pride.

As a reporter noted, “She wears it around her neck all day and parades it along the back fences at night when she sends up her war cry of defiance to the anti forces.”

One of Pussy Suff’s best friends at the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Party headquarters was Mrs. Charles Winslow, leader of the movement in the Third Assembly District. She never missed an opportunity to pet the cat, and the cat would sometimes allow her to pick her up, such as when a photographer snapped the picture above in 1915.

On the other side of the fence, so to speak, was the Brooklyn Auxiliary New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. As one newspaper noted, the Anti-Suffs, as they were called, were prone to adorning their dogs with anti-suffrage pennants and making their cats “look very indignant” by placing anti-suffrage ribbons around their necks.

One of their mascot dogs who never went out in public without his anti-suffrage pennant was Bob Williams, “a dog of fine family” who belonged to Miss M. Panette Williams. Miss Williams was an active worker in the fight against giving women the right to vote and took charge of the cake an candy sales that the women held outside their headquarters at 320 Livingston Street.

Like Pussy Suff, Bob Williams was proud of his neck adornment, and any attempt to remove it was met with growls (anyone dopey enough to be persistent in their efforts to remove the pennant were punished with a nip on the hand or leg “in a very business manner.”)

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter summarized Bob William’s conversations: “Bowwow, bowwo, grrrrrr!!” Translation–“Opposed, opposed, no votes for women!””

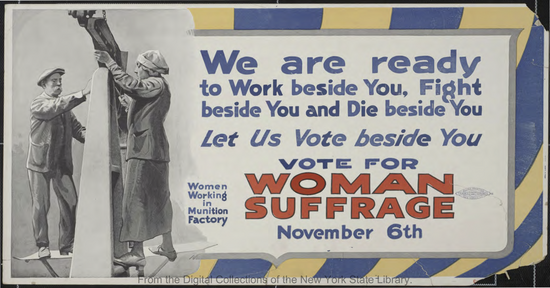

In addition to their cheerleading cat, the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Party had its own car, called “The Suffrage Winner.” The vehicle was driven by Miss Helen J. Owen, who worked as an ambulance driver and mechanic at the First Northumberland VA Hospital in England. The women said they would drive around and ring the car’s liberty bell until the women of New York won the right to vote.

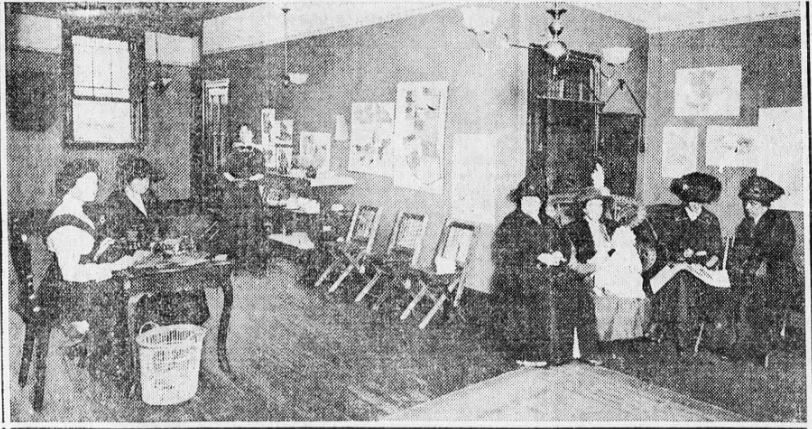

In April 1916, the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Party moved from their little shop on Lafayette Street to “the daintiest little doll-house one could imagine” at 342 Livingston Street.

The new headquarters had pussy-willows and tulips in the window, but I do not know if Pussy Suff was invited to move there or not (the new headquarters was only about a block away from the headquarters of the Anti-Suffs, so if the cat was invited, she would have been close to her rival, Bob Williams).

The new headquarters comprised an anteroom, an office for the secretary, Miss Elfrieda Johnstone, a committee room, a kitchenette, and a large library and lounge in the back. The space was reportedly decorated to perfection in blue and yellow tones, with each piece of furniture made to order.

A Brief History of the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Assocation

The suffrage movement in Brooklyn got its official start in 1868, when Anna C. Field hosted the first meeting of the Brooklyn Equal Rights Association in her home at 158 Hicks Street. About 20 men and women met that evening to show their support for “the promotion of the educational, industrial, legal and political equality of women, and especially the right of suffrage.”

One year later, in May 1869, the association organized at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The group’s first president was Reverend Celia Burleigh, America’s first ordained Unitarian minister and a founding member of Solaris, the country’s first professional women’s organization. Burleigh believed every person had a right to individuality and that the right to vote assured “that [every woman] would one day belong to herself, live her own life, think her own thoughts and become a woman in a better sense than she had ever yet been.”

The association was renamed the Brooklyn Woman Suffrage Association in 1883. Monthly meetings in which the women discussed various legal rights involving their children, wages, jobs, and everything else, it seems, but their rights to have their first names published in newspapers if they were married, took place on Fridays at different homes throughout Brooklyn, including 155 Pierpont Street, 114 Pierrepont Street, and 80 Willoughby Street.

In November 1912, the group established permanent headquarters on the second floor of 27 Lafayette Avenue. Two years later, the group moved down to the ground floor, which opened the door of opportunity for a neighboring black cat with seven toes to stroll inside and make herself at home.

Although the Brooklyn women would ring their car’s liberty bell until November 6, 1917, which is when women won the right to vote in New York State, it would be almost another three turbulent years until the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote was ratified, 72 years after the struggle for women’s suffrage began.

If you enjoyed this story, you may also want to read about Lem and Tiger, the Republican and Tammany Hall mascot cats in 1898.