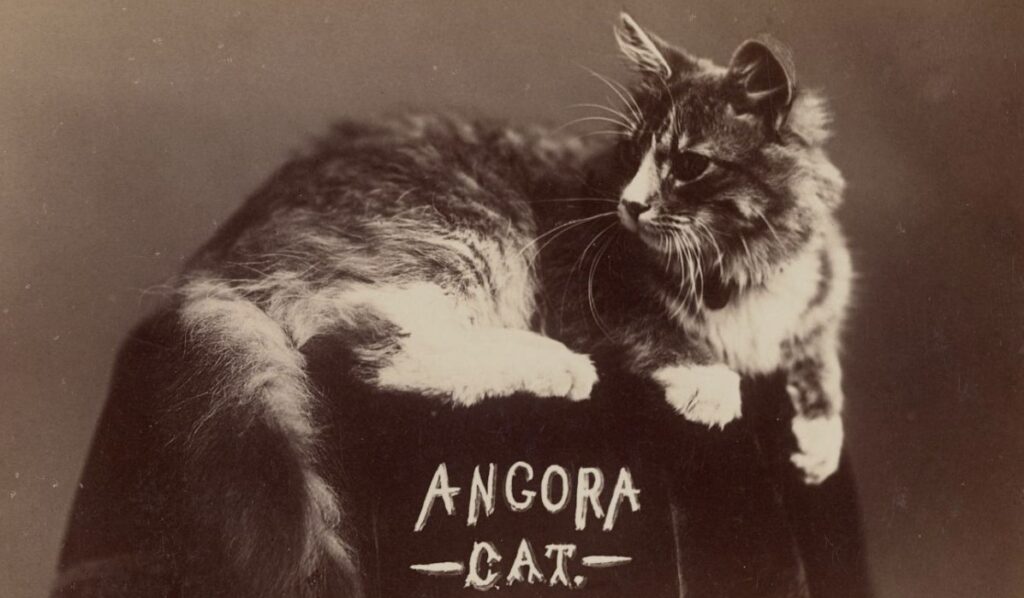

The following story of the Brooklyn Robins feline mascot is featured in my book, The Cat Men of Gotham. It’s a great “Did You Know?” story to share with the cat lovers and baseball fans in your life. The tale also has ties to the Old Stone House of Gowanus, which played an important role during the Revolutionary War.

“A sudden rise from rags to riches in 48 hours–cat-egorically speaking–is not the lot of every coal black kitten…Doubtless Victory will high-hat the cats that knew him before he was adopted by a big league ball team.”–Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 30, 1927

On the evening of April 28, 1927, the manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers (then called the Brooklyn Robins) baseball team was in a bit of a conundrum. Just 14 games into the season, the downtrodden team–also called the Flock, the Daffy Dodgers, and Uncle Robbie’s Daffiness Boys–had won only 2 games.

In the past week, the Brooklyn Robins had lost 5 straight games to the Boston Braves, New York Giants, and Philadelphia Phillies. Tasked with pulling a rabbit out of the hat, “Uncle Robbie” Wilbert Robinson, the team manager, was desperate for some good luck.

Enter stage right not a rabbit but a 3-month-old, all-black vagrant kitten that grew up in the shadows of the Brooklyn Bridge.

According to a report in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Robinson had been in his apartment parlor when he heard a tapping noise outside his chamber door. When he opened the door to investigate, he met a stranger holding a coal-black kitten.

“Mr. Robinson, here is something to break the jinx,” the man said. “I found it outside.”

“Black cats are bad luck,” Robinson said with a gasp.

“Sometimes,” the stranger replied. “But it takes a thief to catch a thief and maybe it takes a jinx to lick another jinx.”

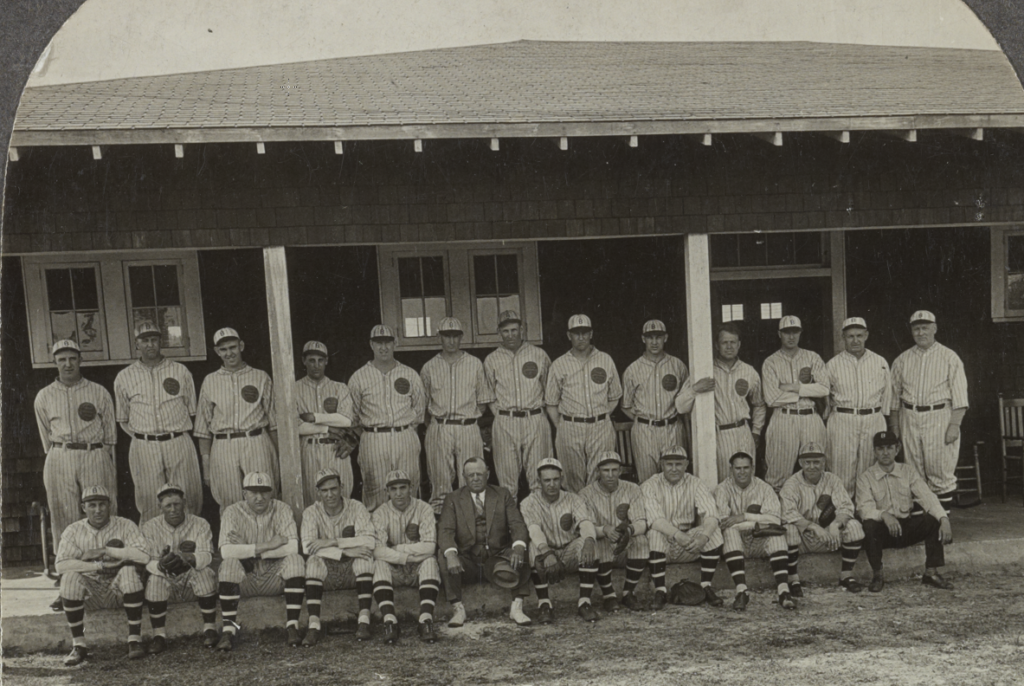

The stranger convinced him. The next day, Robinson created quite a stir when he strolled into the Ebbets Field clubhouse with the kitten perched on his left shoulder. The players were horrified at first, but Robinson explained about the jinx and suggested that the team give the cat a 3-day trial.

“And you’re going to treat him right in the meantime,” he added. The team listened.

As the Brooklyn Robins team prepared for its game with the Phillies, the kitten calmly explored each corner of the clubhouse. The lefty pitcher William Watson “Watty” Clark prepared a little soapbox house in a corner behind some trunks and asked Babe Hamberger, the clubhouse boy, to buy milk.

Clark also brought the kitten over to the southpaw pitcher Big Jim “Jumbo” Elliott and ordered him to pat the kitten’s head for good luck. Elliott held the cat in his right palm and stroked him with his left fingers. The tiny kitten all but disappeared enveloped in the large man’s hands.

In that evening’s game against the Phillies, Elliott was practically unhittable. Not one opposing-team player reached third base. Only one player reached second. The Brooklyn Robins had 10 hits and beat the Phillies 7-0.

Following the shutout, the Brooklyn Robins christened the kitten Victory, going as far as breaking a bottle of milk over a chair and letting the milk pour down on the poor cat. The players then carefully groomed Victory and prepared him for the third and last game in the Philadelphia series.

The Brooklyn Robins went on to win the next 4 games against the Phillies and the Giants.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle had fun with the cat, even going as far as interviewing a man who claimed to be the cat’s interpreter. The man, Lee Ehret, ran the cigar and candy department at the Yaffa brothers’ drug store adjacent to the Hotel St. George on Clark Street, which was nowhere near the stadium.

According to Ehret, Victory’s real name was Oswald, and the cat was a very respectable feline who spent much of his time near the Hotel St. George (the cat especially loved the drug store’s catnip department.)

“I’ve never been a vagrant cat. Nor have I ever associated with bums,” Ehret said in the first person, as if the cat were speaking through him. He also denied rumors that Victory was born in Australia. “How could an Australian black cat pull a ball team out of a slump? They play cricket there.”

About a week after Victory arrived, a Brooklyn Robins fan slipped another cat to right fielder Floyd Caves “Babe” Herman prior to a game at the Polo Grounds. Babe put the cat in his locker and went on to hit two home runs during that game. The following day, though, he did not get one hit in five at-bats.

Asked about the feline interloper following the Polo Ground games, Victory said (through his human interpreter) that the new cat “lacked consistency” when it came to luck and was probably just an alley cat who could not hold a candle to him.

The Amsterdam Evening Reporter also “interviewed” the cat about how he brought luck to the downtrodden team. “I did it for the wife and the kitties,” was Victory’s response.

I don’t know how long the rags-to-riches kitty remained with the Brooklyn Robins, but I do know he lived in luxury during his time as the team’s mascot, enjoying milk every day and fish on Sundays.

Alas, not every cat can be a miracle worker. The team finished the season in sixth place out of 8 National League teams, with a record of only 65 wins and 88 losses.

Incidentally, Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca brought a black cat to Ebbets Field on April 13, 1951. By holding the cat and displaying the number 13 on his uniform, Branca was reportedly sending the New York Yankees a message that his team was not afraid of any bad-luck signs on that Friday the 13th.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were lucky that day, winning the game by a score of 7-6.

This concludes the story of Victory and the Brooklyn Robins; the following two sections are for those who appreciate baseball or Brooklyn history.

The Brooklyn Base-Ball Club and Washington Park

Semi-pro and pro baseball in Brooklyn goes back as far as 1855, when the Brooklyn Atlantics (named for Atlantic Avenue) formed as one of 16 clubs–all from Manhattan and Long Island–comprising the National Association of Base Ball Players. But Victory the cat was associated with the team that originated as the Brooklyn American Alliance Base-Ball Club (aka the Brooklyns) in 1883.

The team would go by various other nicknames, including the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, Superbas, and Robins until 1932. From 1932 to 1958, the team was officially known as the Brooklyn Dodgers.

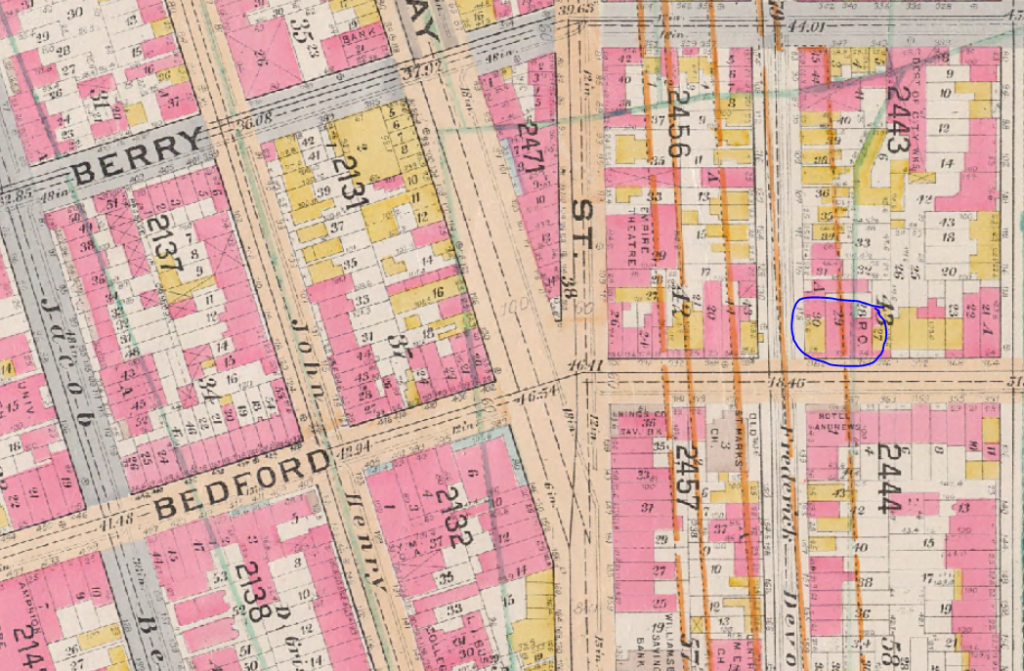

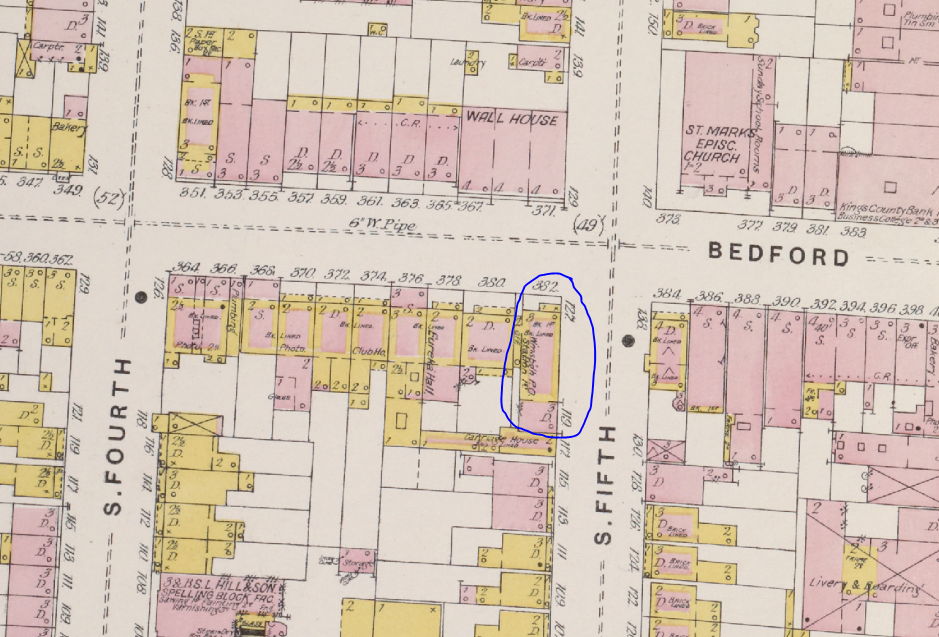

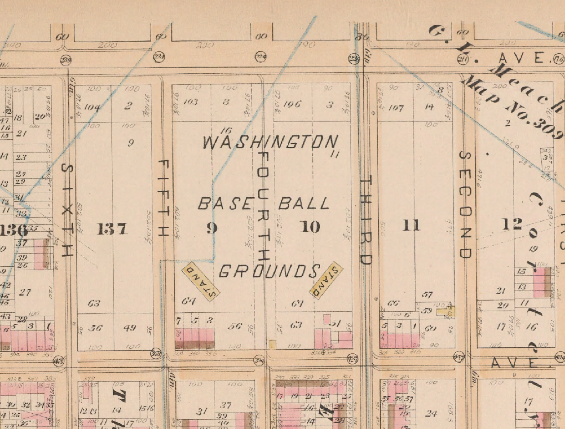

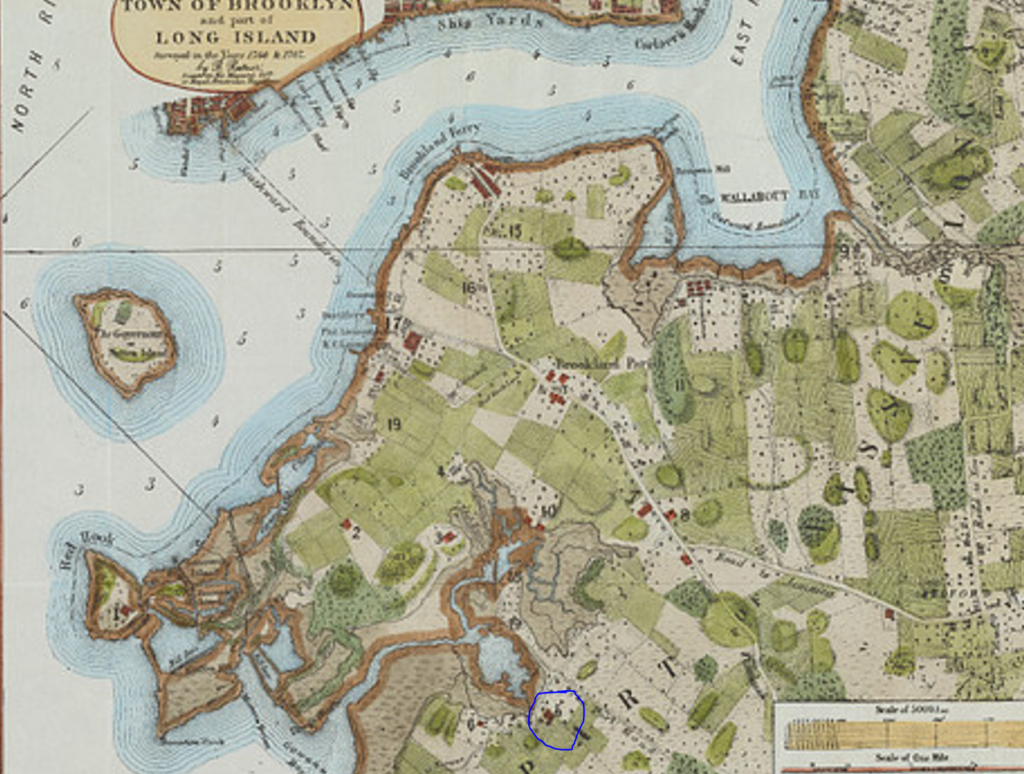

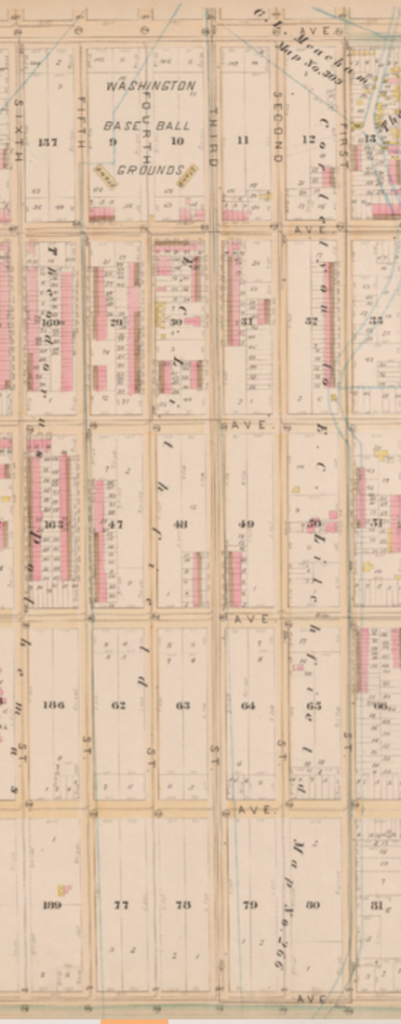

In 1883, a real estate tycoon and baseball enthusiast named Charles H. Byrne set up grandstands on Fifth Avenue between Third and Fifth Streets in what was then called South Brooklyn (now Park Slope). He named it Washington Base-Ball Park in honor of the site’s historical ties to George Washington and the Revolutionary War.

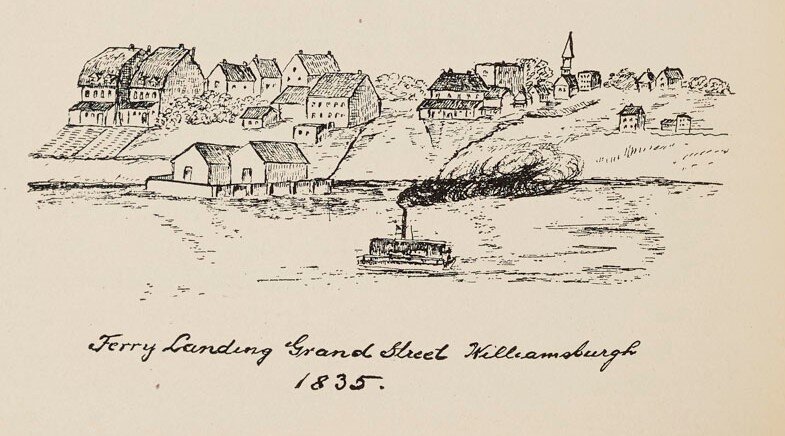

The new ball park was built on what was once a swampy hollow of grasslands near the shoreline of the old Nehemiah Denton Mill Pond and the Gowanus Creek. This marshland was part of a larger parcel of land then owned by the estate of Edwin C. Litchfield, a prominent Park Slope developer.

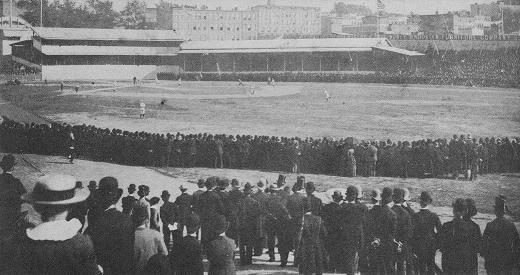

The marshy grounds, littered with the city’s ash can waste and spongy from stagnant water, were drained, graded, and leveled; a fence was also erected around the parallelogram-shaped field. The park had a grandstand for about 2,000 paying spectators on Fifth Avenue and large open stands for another 2,000 non-paying fans on Third Street.

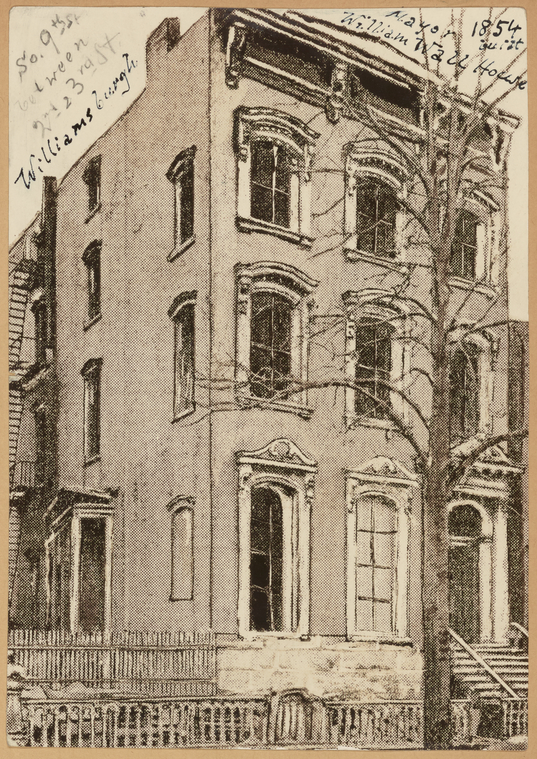

The main entrance to the park was on Fifth Avenue, but wooden steps on Third Street led down to the colonial-era farmhouse that had been on the site for almost 200 years.

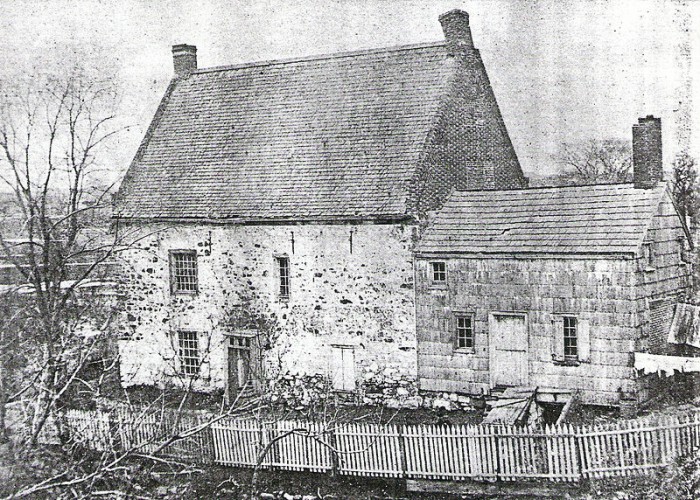

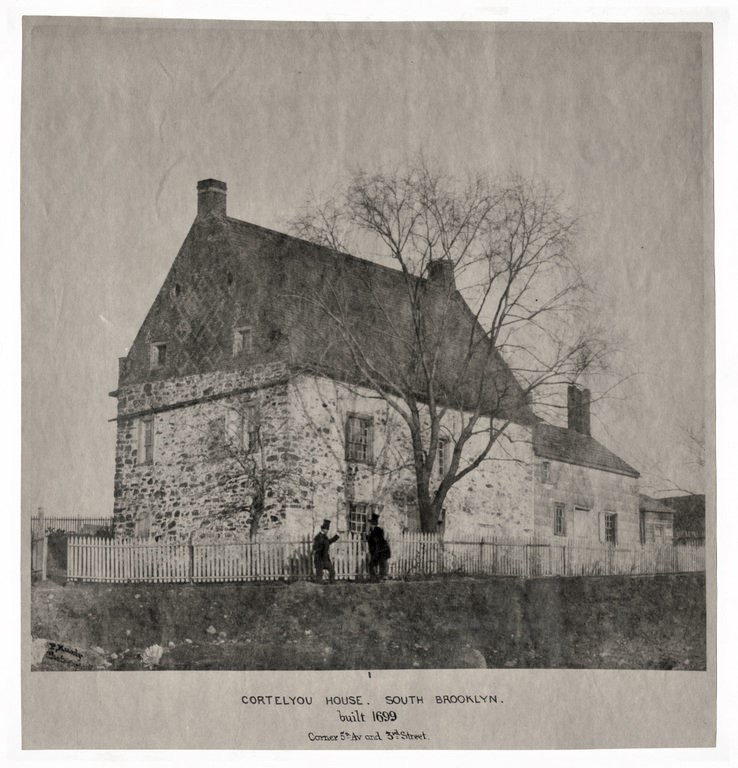

Back then, people referred to the old house as the old Cortelyou house or as Washington’s headquarters, even though Washington never based his operations here (I don’t even think he slept in the home). In later years, it would be known as the Old Stone House of Gowanus.

In 1883, the old farmhouse no longer had doors, windows, or a complete roof, but the team fixed it up and put up a new tin roof, and used the dilapidated building as their clubhouse (or dressing room, as they called it back then).

Fifty years after the park opened, Brooklyn old-timer Thomas Fox told a reporter for the Brooklyn Times Union that the Old Stone House was in line with home plate on the right field side, and many foul balls bounced off its sloping roof. He also said there was a carriage entrance on Fourth Avenue that buggy owners could use to drive onto the center field.

According to Fox, it was a common to see peddlers’ wagons in the park, and many doubles and triples became home runs when the ball went under the horses’ legs. One day a ball hit a horse in the neck, and the horse bolted toward home, almost beating a base runner to home plate.

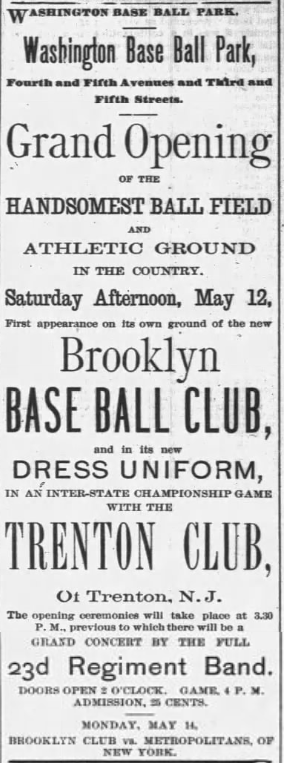

In their inaugural season, the Brooklyn Base-Ball Club played in the minor Interstate Association of Professional Baseball Clubs. Their first home game, which was also the grand opening of the Washington Base Ball Park, was Saturday, May 12, 1883 (they beat Trenton 13‑6). The players included Kimber and Corcoran and Terry and Farrow (batteries); Householder, Greenwood, Warner, and Geer (infielders); and Smith, Walker, and Doyle (outfielders).

The press noted that the “gentlemanly team” and large number of women in attendance at the opening game boded well for the beautiful new park and the non-offensive yet “manly sport” of baseball. As Byrne told the press that year, “no contract-breakers, drunkards, or crooks” would be allowed to join the ranks of his team.

The Brooklyns went on to win the league championship in their first season.

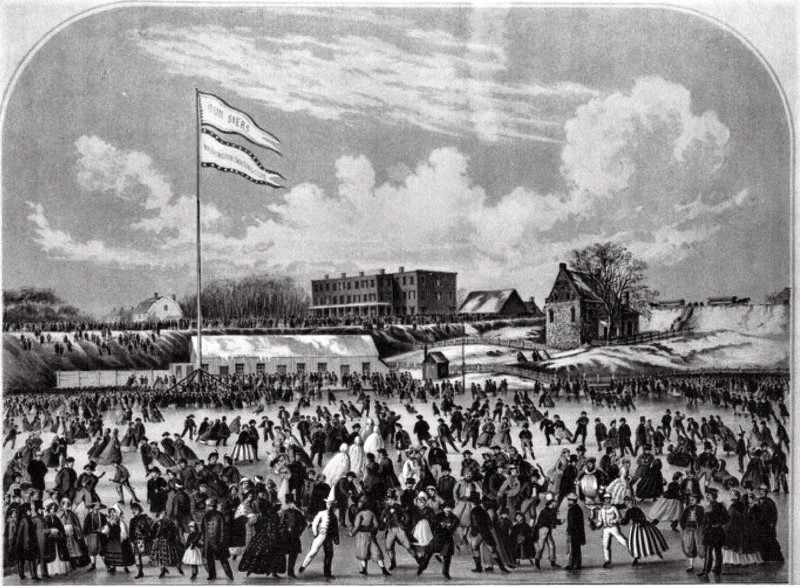

That winter, the field was flooded with 2 million gallons of water to create a lake for ice skating (it was common to flood Brooklyn’s old ball parks to create skating ponds in the 19th century). The grandstand was partially enclosed with a glass front to serve as a ladies’ reception and lunch room from which they could watch their children skate. The Old Stone House was fitted up as a restaurant and a lounge for the men and boys.

The following year the team joined the American Association (AA), a competitor to the more established National League (NL). The Brooklyn didn’t do too well, finishing ninth in the league.

A large fire in May 1889 destroyed the grandstand and fencing, but the fire did not burn the free stands or the Old Stone House, where the men kept their uniforms and other belongings. However, the fire did prevent the team from playing at their home field that year.

The Brooklyns would play only two more seasons at Washington Base Ball Park before heading to Brownsville, where they’d get a new nickname: The Trolley Dodgers.

In my next post, I’ll tell you how the team got this nickname and share a story about some cows, goats, and pigs that lived on the land that would become the team’s new home park in 1898.

If you’re interested in Brooklyn’s colonial era or the city’s role in the Revolutionary War, continue on. I dug up (pun intended, as you’ll see later) quite a bit of information about the historical Old Stone House, including firsthand reports from those who lived in the neighborhood in the mid-1800s.

A Comprehensive History of the Old Stone House

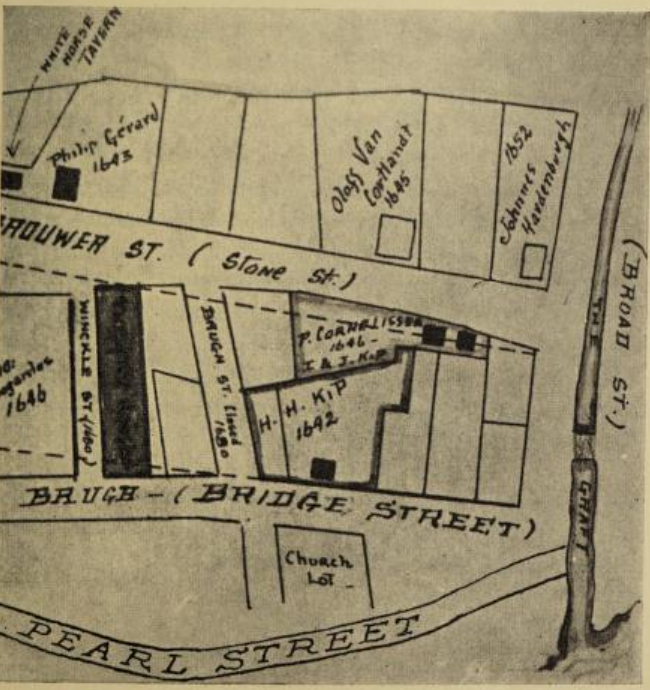

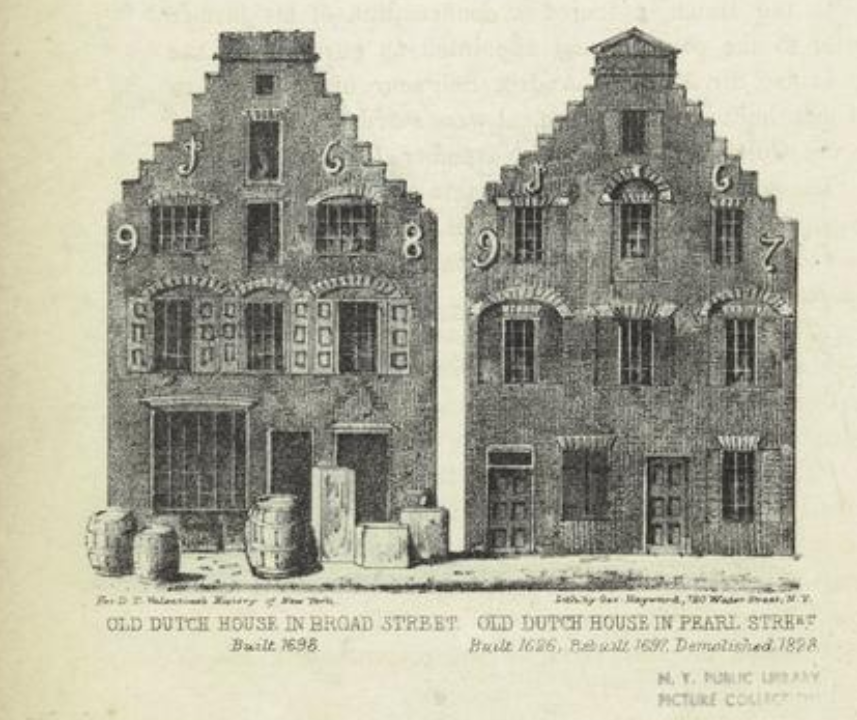

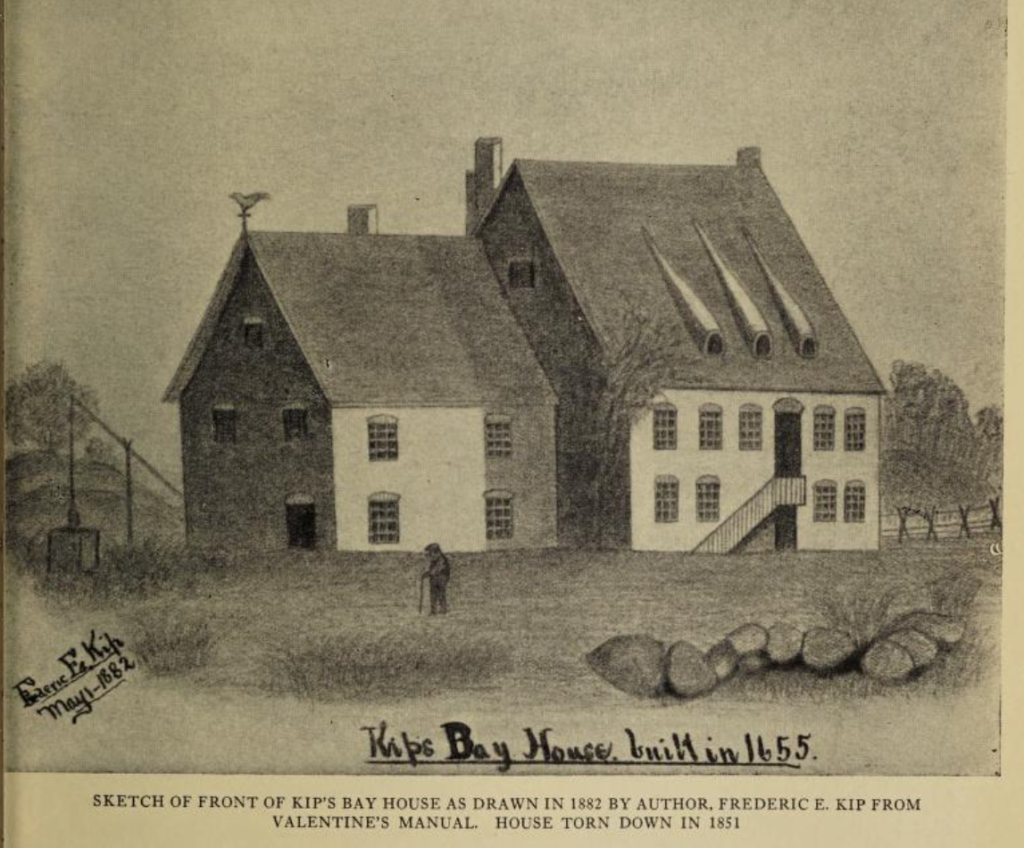

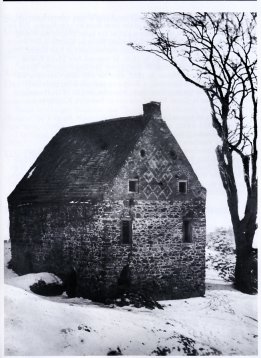

The Old Stone House was built for Hendrick Claessen Vechte (van Vechten) in 1699. Hendrick was the son of Claes Arentse van Vechten of the Province of Utrecht, Netherlands. When Claes brought his wife and three children to America in April 1660, Hendrick was about six years old.

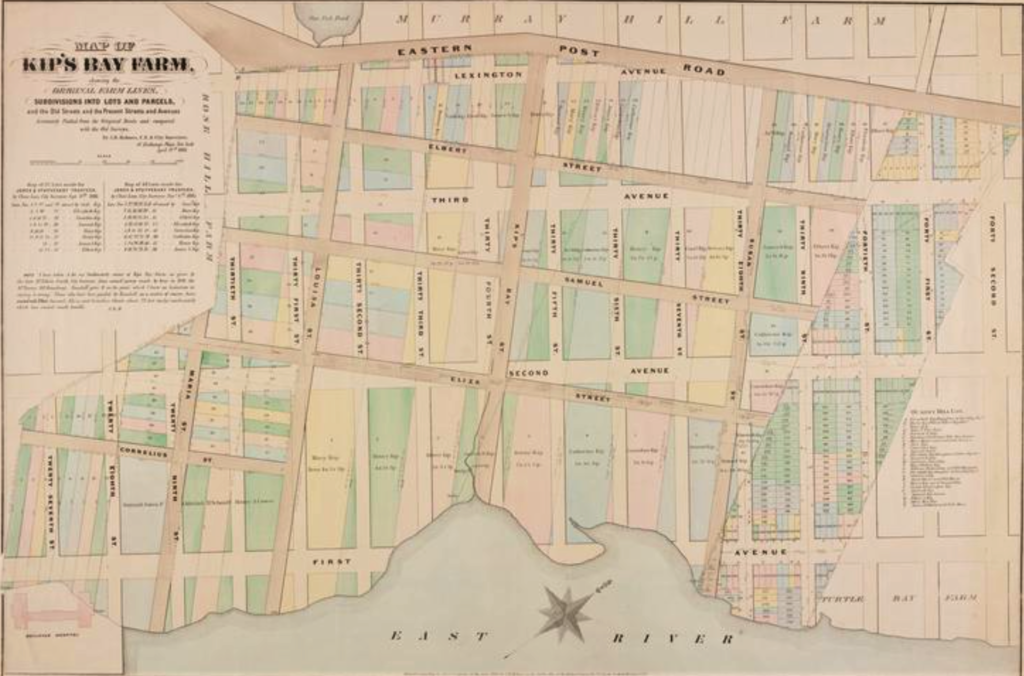

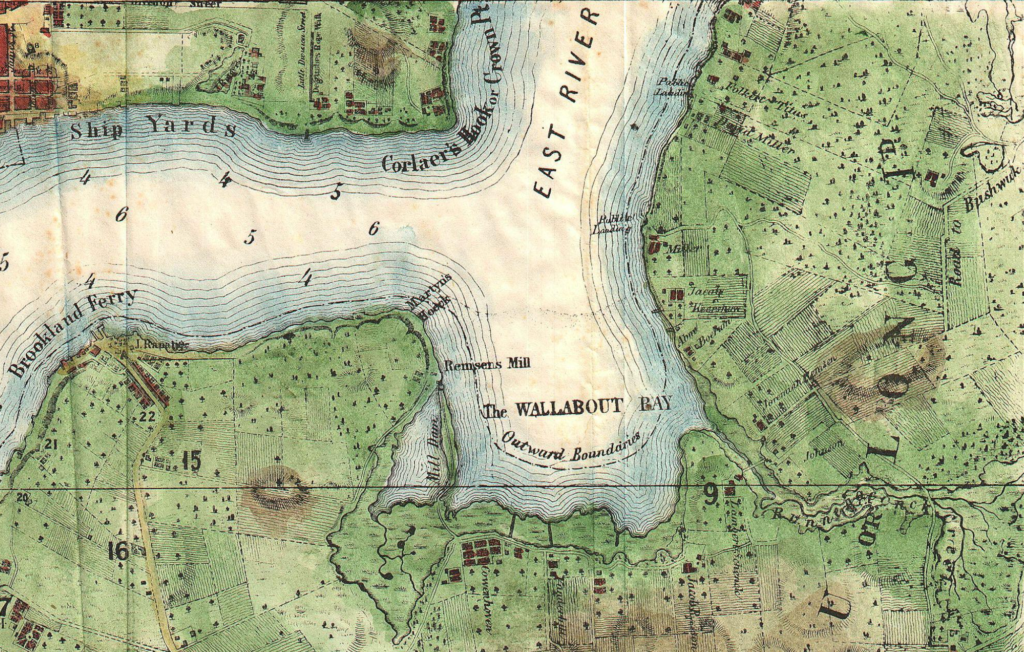

The Vechte farm, established sometime around 1670, was along the Gowanus Creek, near the village of Gowanus. The large farm of about 150 acres extended from the present-day Gowanus Canal, between First and Sixth Streets, to the western edge of Prospect Park, where the 1855 Litchfield Villa still stands.

Much of the Vechte land was in the lowlands, which was mostly grassy salt marshes where the family’s cows could roam. According to records, the family had 28 acres of cultivated land as well as a horse and seven or eight cows in the mid 1670s. They also had at least one servant boy and one African slave.

Hendrick married Gerritje Reyniers Wizzelpennig in 1680, and the couple had 9 children (only 6 survived into adulthood). In addition to working as a farmer, carpenter, and wheelwright, Hendrick was a Justice of the Peace, appointed by William III. The family was quite well off, and their elegant stone house–the only stone house in the area–was a noticeable display of that wealth.

All of Hendrick and Gerritje’s children save for their son Nicholas moved away from the area, leaving the house and land to Nicholas and his wife, Cornelia Van Duyn, when Hendrick died in 1716. Gerritje lived in the home until her death at the age of 94 in 1754.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, Nicholas was a prosperous farmer and fisherman, selling oysters and fish from the bay and crops from his orchards and gardens to the New York markets. He took advantage of the surrounding ponds and springs to dig canals on his property for transporting the produce to Manhattan.

The Battle of Brooklyn

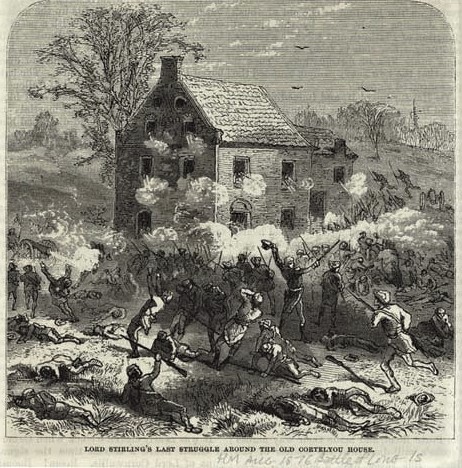

The Old Stone House was the scene of one of the largest and deadliest battles of the Revolutionary War, during the Battle of Brooklyn (aka Battle of Long Island).

On August 27, 1776, American General William Alexander (aka Lord Stirling), led a regiment of 400 Maryland soldiers against British troops who had occupied the house and were shooting at American troops trying to cross the Gowanus Creek. The Maryland troops made five valiant charges at the Old Stone House, but they were no match against 2,000 British soldiers.

Most of the Maryland soldiers were killed on Nicholas Vechte’s lands this day, turning the green grass and clear waters crimson. But their brave efforts allowed General Washington and the bulk of his troops to escape across the Gowanus Creek and East River.

Nicholas Vechte died during the midst of the war on September 9, 1779. He was buried on the farm, possibly near Third Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. The farm passed to his young grandson, Nicholas R. Cowenhowen.

Following the war, the Old Stone House, now bloodied and battered in battle, stood deserted for several years. In 1790, Cowenhowen sold the homestead and farm to Jacques Cortelyou, whose family would occupy the home for more than 50 years.

The last of the Coretelyous to own the property were grandsons Jacques and Adrian, the children of Jacques’ late son, Peter I. Cortelyou.

The brothers split the property in half, with Jacques conveying his portion to Sandford Coley in May 1851 and Adrian conveying his half to Park Slope developer Edwin C. Litchfield on November 1, 1852. Five days later, Coley sold his land to Litchfield, making Litchfield the sole title holder to the old Vechte farm, at a total cost of about $150,000. The only house on all this land was the old Vechte-Cortelyou house.

Litchfield had no intention of living in the house or maintaining the farm, but he was able to rent the home for a decade or so. One of the occupants was Nathan Collins; his son Ferdinand A. Collins also lived in the home sometime prior to 1865.

It would be many more years before Litchfield would start developing the marshy lowlands that he had purchased. With taxes fairly low for the soggy marshland, he probably thought it best to hold onto the empty land and allow the value to grow until the right opportunity–like a city park or baseball organization–came along.

Skating and Ice Baseball at the Old Stone House

In January 1860, 18 residents, including E.B. Litchfield and Edwin C. Litchfield, submitted a proposal to the Park Commissioners of the City of Brooklyn suggesting that the city purchase some lowlands to create a public park bounded by Third and Sixth Streets and Fourth and Fifth Avenues. The abundance of water on the property, they said, would be ideal for creating a pond for swimming and skating, and the Old Stone House could serve as an historical museum. They suggested calling the park Stirling Square.

The park proposal would have relieved Litchfield of that portion of his lands that would be most costly to improve. No action was taken on this forward-thinking proposal (that wouldn’t happen for another 72 years), but park or no park, the public did use the land for swimming, baseball, and skating.

During mid-1800s, all the lowland from Third to Butler Streets between Third and Fourth Avenues would flood over and freeze (the ground was 15 to 40 feet below street level then), creating plenty of opportunities for skating. As one old Brooklynite wrote in a letter to the Brooklyn Chat in February 1924:

“It was my good fortune to live in South Brooklyn–almost country then–way back in the ’60s, and we children did most of our skating on the big pond between Fourth and Fifth Avenues. We would take our skates to school with us in the morning; then at 3 o’clock, books under one arm, skates dangling from the other, would run off to the pond.

We always went into the house to get a bit warm and leave our books with ‘Grandpa’ and ‘Grandma,’ as we called the kind old couple who lived there. I do not think these folks received any remuneration for looking after the children–may have had rent cheap or something like that. They just wanted to be nice to us, and we adored them!”

In the early 1860s, skating clubs such as the Brooklyn Skating Club and Washington Skating Club attracted thousands of people to the frozen waters around the Old Stone House.

The Washington Skating Pond (comprising about 7 or 8 fenced-in acres) originated as a private skating pond in 1860 and was run by Major Oscar F. Oatman, a journalist and advertising agent who also ran several other skating rinks. The Major often arranged “fancy dress skating carnivals” at the frozen pond.

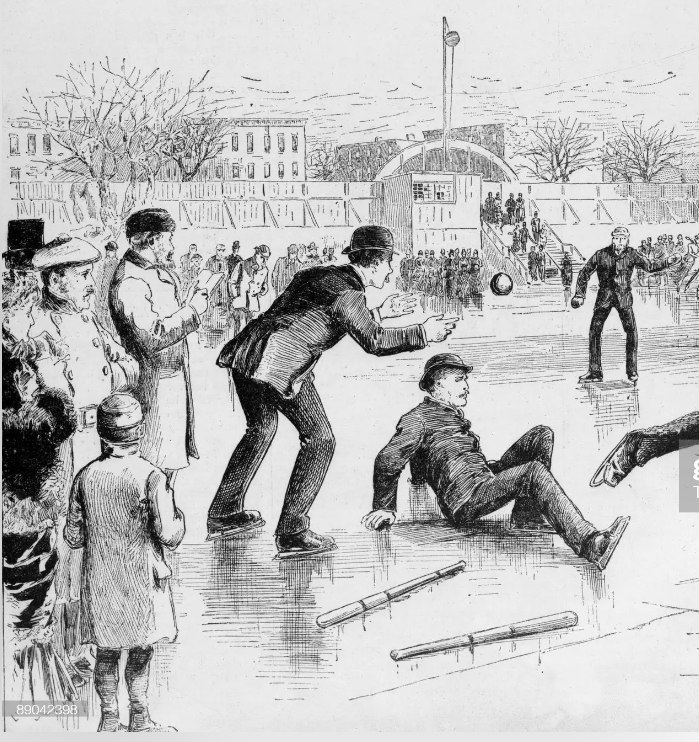

Some of these skating events combined the game of baseball, which created an exciting winter sport called ice baseball or baseball on ice. Because the players couldn’t easily stop on ice, a new rule that baseball still follows was formed: base runners were safe at first base simply by over-skating (overrunning) the baseline.

By the end of the decade, the pond had all but disappeared, courtesy of street grading and paving–much of the work done by Litchfield at his own expense to improve his land. In three years, the value of Litchfield’s land would quadruple.

From 1866 to 1869, 60 new brownstone-front and brick mansions went up on Litchfield’s land, mostly along Fifth Avenue near Third Street and on Third Street from Fifth to Seventh Avenues.

It was also Litchfield, who, as president of the Brooklyn Improvement Company, created three branch canals leading from the Gowanus Canal during this time period. These canals still exist between Fourth and Eighth Streets.

The End of the Old Stone House

After the Brooklyns moved out of Washington Park in 1891, P.T. Barnum’s circus pitched its tents on the grounds along Fourth Avenue and Third Street for many years. During this era, the former ball park then became a dumping ground, “where clowns and monkeys prance[d] over the graves of our heroes.”

Around 1894, the city began filling in the site as part of another street grading project. According to James K. Macartney, who wrote about the site in 1933, part of the house was buried, but the second story was still accessible on Third Street; a large door was cut into a wall to allow a butcher to use the building as a stable.

Sometime between 1897 and 1899 the sturdy walls that still remained above ground were partly demolished, and some of the stones from that demolition were used to form a retaining wall around the buried remains of the building. The old willow tree–planted by James Cain and his young son Samuel about 1840–continued to flourish, though almost completely buried, until it fell down during a storm around 1910.

Over the next decade, the old house would disappear completely underground.

Although the Brooklyn League proposed building a playground on the site in 1910, no action was taken. In fact, the earth over the Old Stone House wouldn’t begin to move until 1922, when word got out that the Litchfield estate was going to auction off the old Washington Base Ball Park.

The Kings County Historical Society, led by president Charles A. Ditmas, asked the city to purchase the land for use as a public park. But the Brooklyn Edison Company had already jumped in, purchasing all 107 lots for $126,000 before the auction even took place. The company planned to construct a large power plant and storehouse on the historic property.

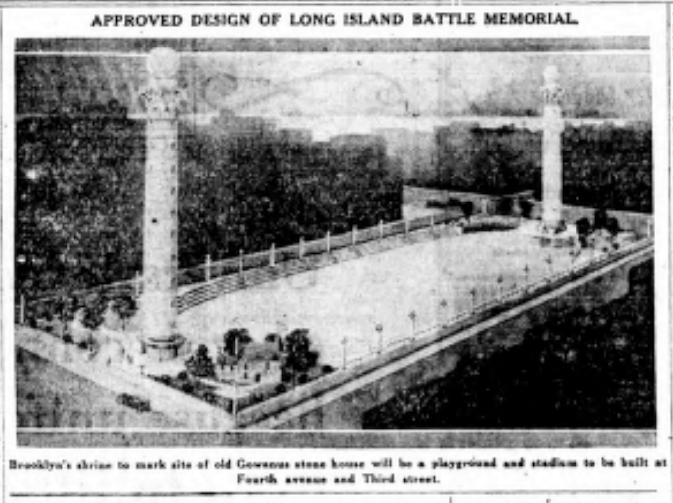

As the movement to save the Old Stone House gained momentum, Brooklyn Edison agreed to put their plans on hold until the city could ascertain whether there was a strong sentiment for its “rescue and perpetuation as a shrine of American patriotism.” Patriotism won out. A year later, on July 1, 1923, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the ground would be dedicated as a park called Memorial Park.

Although the city purchased the site in 1925, the park, including a proposed shrine, didn’t materialize. In 1927 the Polytechnic Institute announced its desire to purchase the land back from the city for a new building.

The Kings County Historical Society jumped in again, and a group of citizens led by William J. Dilthey brought a suit against the borough to prevent the institute from building there.

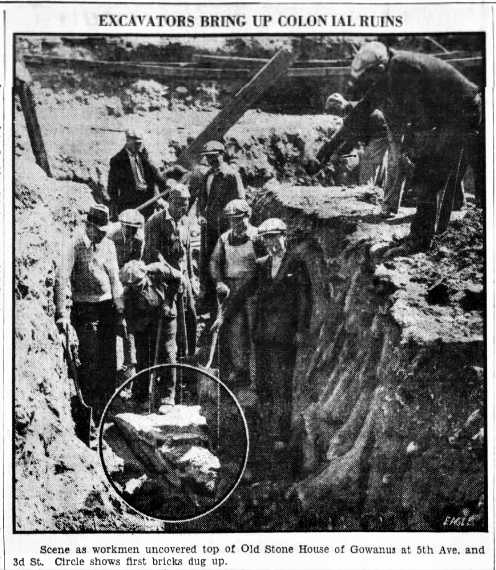

Following years of controversy and numerous appeals, the city (and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses) finally agreed to undertake an emergency work project and build a playground on the site as part of the Emergency Work and Relief Bureau. On April 17, 1933, 130 previously unemployed workers began digging in search of the Old Stone House.

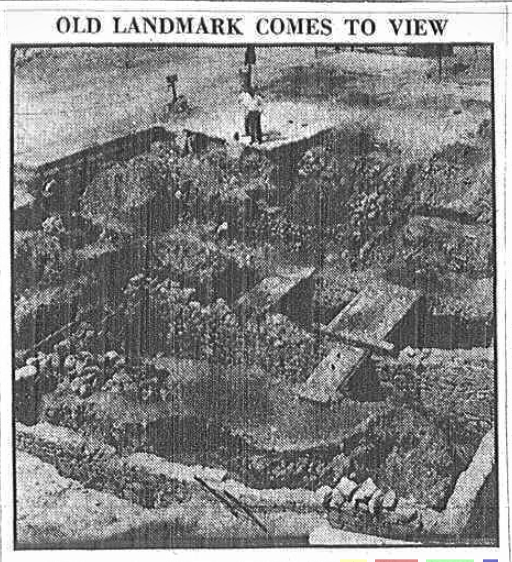

After weeks of unsuccessful digging, several old-timers came forward to point toward where they believed the house was buried. On May 4, 1933, the diggers struck its northwest corner about 12 feet down. It turned out to be the top of the old house, minus a roof.

The workers had to dig down about 30 feet to unearth the complete structure. They salvaged the old stones to build a new house modeled on the original Vechte farmhouse.

On August 11, 1935, JJ Byrne Playground opened to the public. The playground was one of 203 playgrounds opened that year as part of Robert Moses’ playground construction program.

In addition to ballfields, handball and basketball courts, and a wading pool, the playground featured a two-story community center, previously known as the Old Stone House of Gowanus.

Today, the Old Stone House and Washington Park is part of the Historic House Trust of New York City and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.