There was a deep gloom pervading the quarters of Fire Patrol 3 on West Thirtieth Street in August 1915. As the New York Sun noted, “If it were not for the absence of crape on the door, a visitor would be led to believe that the company had just lost its most popular member. The firemen move about without animation; their fighting spirit, developed through constant battle with fire and smoke, has disappeared.”

The reason for the despair was that Fire Patrol 3 was soon to lose its two beloved feline mascots.

The New York Fire Patrol was a paid fire salvage service organized and funded by the New York Board of Fire Underwriters to protect and preserve property and life during and after fires. Although not officially affiliated with the FDNY, the men worked alongside the city’s firemen and took orders from the FDNY commanding officer. Patrolmen were private civilians, but they were also firefighters trained in the art of salvage, forced entry, and overhaul.

Fire Patrol 3 was formed in 1894, with headquarters at 240 West Thirtieth Street, located in the crime-ridden Tenderloin district. The new four-story patrol house, which opened on September 10, 1895, featured stalls for five horses on the ground floor, a dormitory on the second floor, a large billiard room and sitting room on the third floor, and workshops and supply space on the top floor.

An elevator was in the rear of the building for passengers and freight. Behind the station was a two-story brick stable with feed rooms and a hayloft. This building had two box-stalls with a thick flooring of Irish peat, where the horses could recover from the long, hard runs.

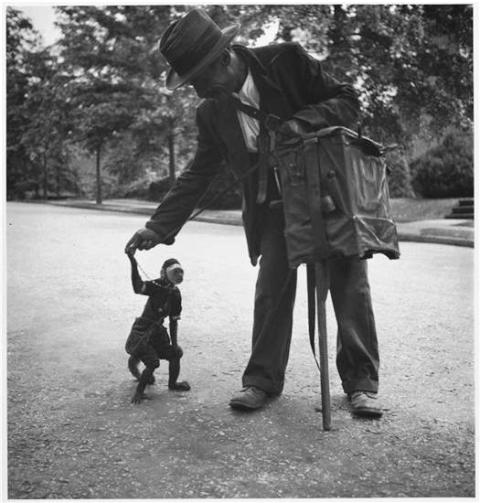

Five years after their new house opened, the patrolmen were still without a mascot. They wanted one, but they did not want a canine mascot. As a salvage corps, the men of Fire Patrol 3 had an immense territory to cover—from river to river and from 14th Street to 57th Street—which made it impractical for them to have a dog trained to follow the apparatus to fires.

So, when the opportunity to acquire a proper mascot presented itself at a fire at Seventh Avenue and Twenty-Eighth Street in October 1900, the men acted immediately.

According to the story, the men were working on an upper floor when they came upon two kittens on a rear fire escape. The kittens had been abandoned by the tenants in their flight to escape the burning building.

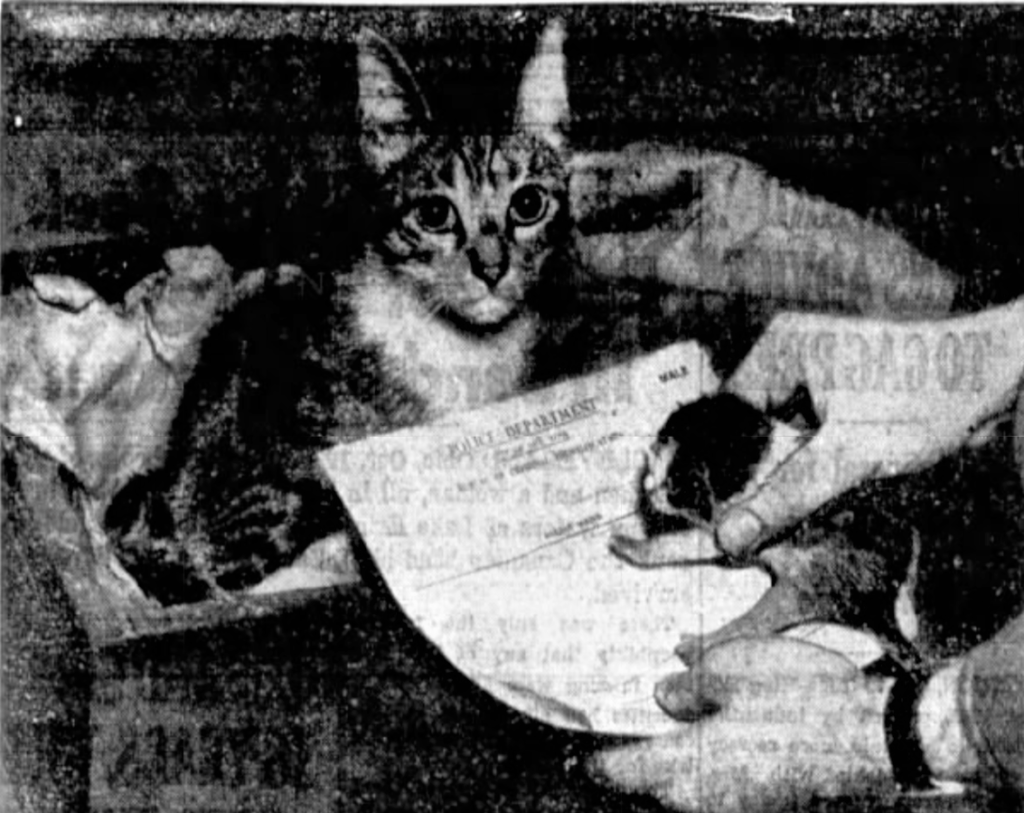

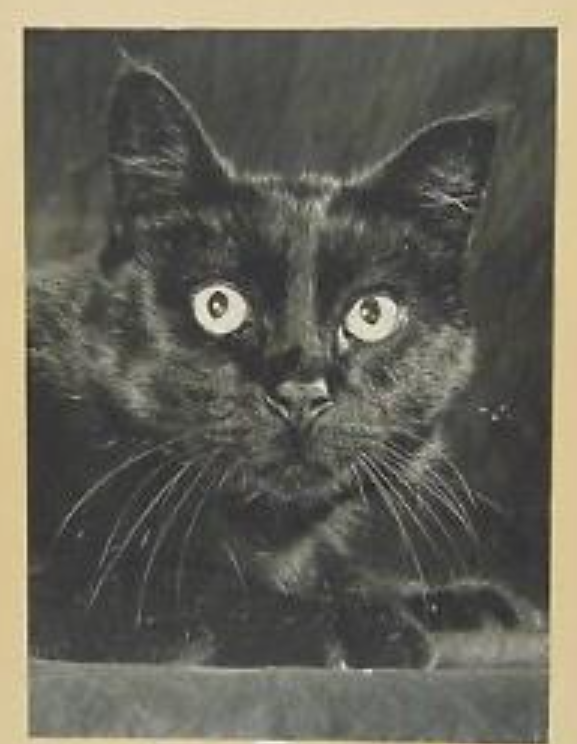

Being trained not to take anything from a fire scene that had an owner, the men tried to find the owners of the kittens. When no one came forward to claim the cats, the men adopted both. They named the tiger-striped kitten Bouncer and the coal black kitten Nellie.*

Bouncer was the more intelligent cat, although Nellie was also a smarter cat than most. Four months after moving into the patrol house, Bouncer had mastered the fire pole, wrapping all four paws around it before making his descent. When it came to the landing, he outdid every member, striking the rubber mat “as gently as an autumn leaf landing on the turf.”

Nellie’s specialty was riding to fire calls, curled up in one of the unused fire helmets.

Three years after Bounce and Nellie moved in, the men took on a pet goat named Willie, who lived with the horses in the stable. Willie got into some chaotic trouble in February 1903 when he took advantage of an open stable door and went on a half-hour romp along Fifth Avenue.

First, he charged at some young boys who were throwing snowballs at him and knocked one boy down. Next, he ran under carriages and several horses, who were not used to seeing goats running loose on Fifth Avenue. He also knocked a few pedestrians down.

As a crowd of cab drivers and small boys with sticks and snowballs chased him, he ran north to the Waldorf-Astoria, knocking down one of the hotel porters. Eventually he made his way back to the stable. As the New-York Tribune noted, “No one had been seriously injured.”

Sadly, by 1915, Willie was no doubt gone and the fifteen-year-old cats were blind and could no longer care for themselves. The thirty-two members of the salvage corps decided it best to put the two cats out of their misery in the most humane way possible. And so, they assigned Captain Jimmy Rice the job of sending for the ASPCA wagon to take them away to a painless death.

Everyone hoped they would not be on duty when the wagon called. Captain Rice told the press that when he signed the death warrant for Bouncer and Nellie, he would not sign his own name. He would only sign “Patrol 3. Commander Officer.”

Additional stories about Bouncer and Nellie will be featured in my upcoming book, The FDNY Mascots of Gotham, coming out next year.

*Nellie was not the cat’s actual name. Like many all-black animals of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, her given name is now an offensive ethnic slur.