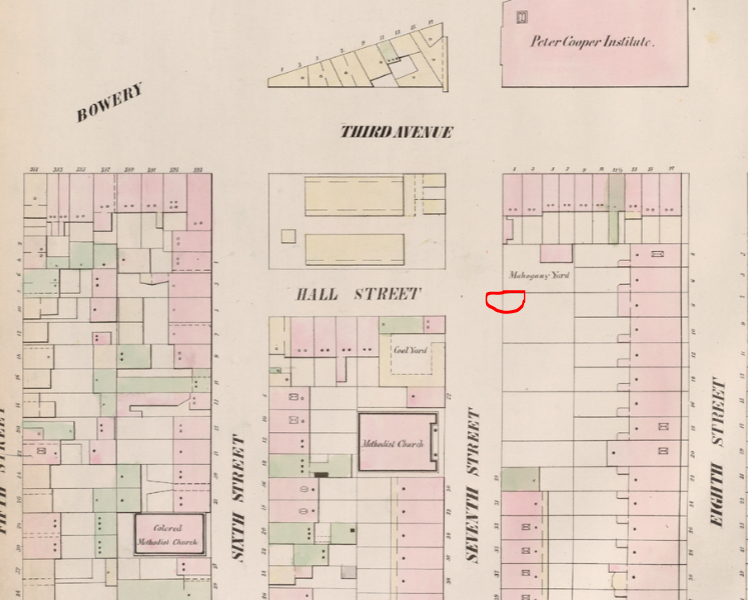

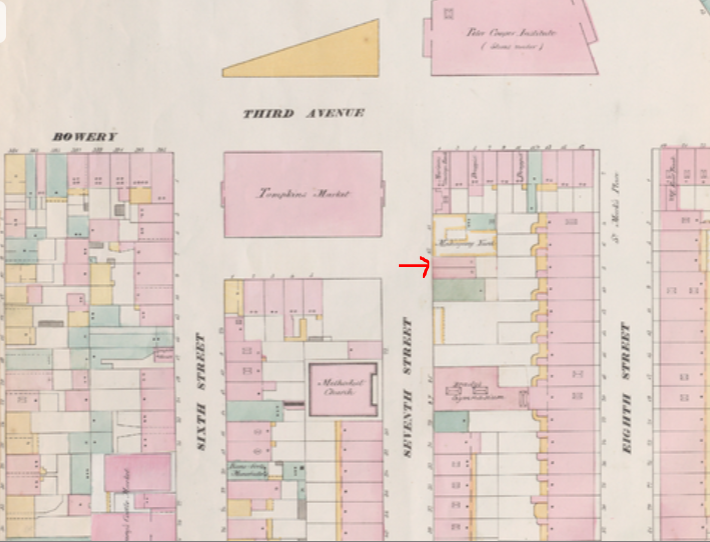

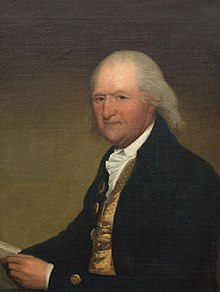

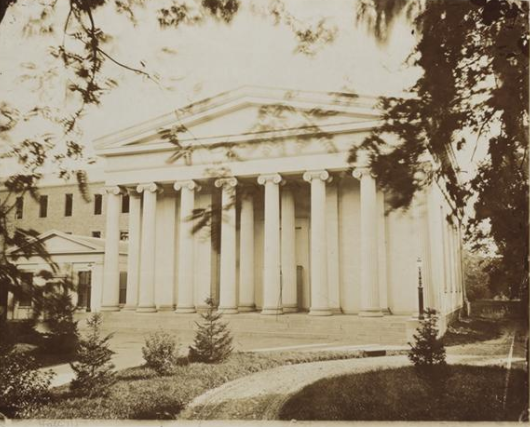

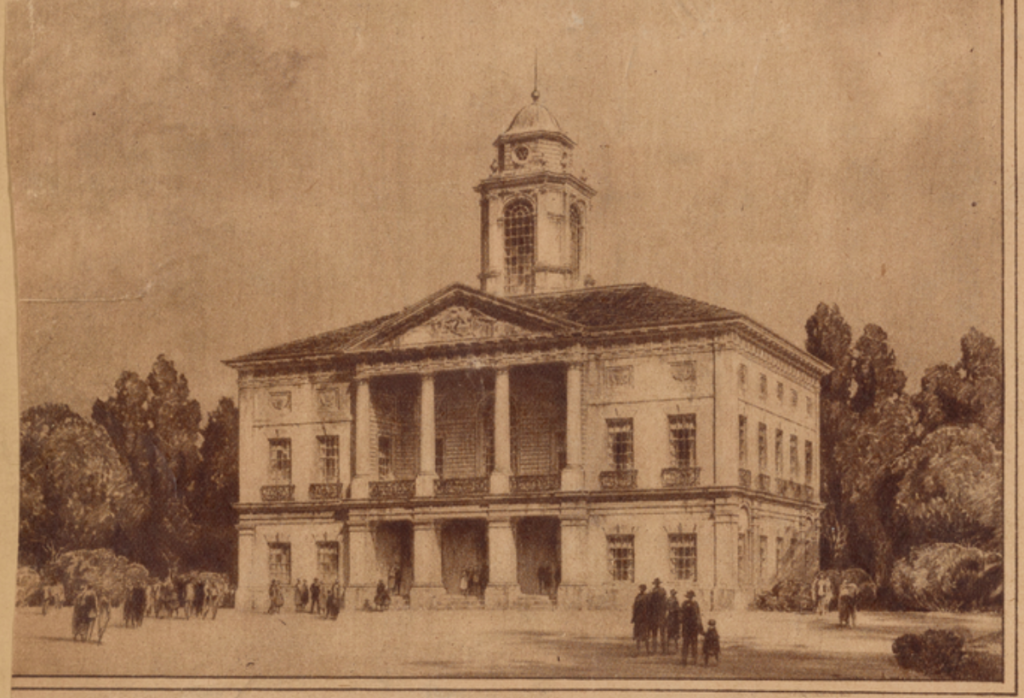

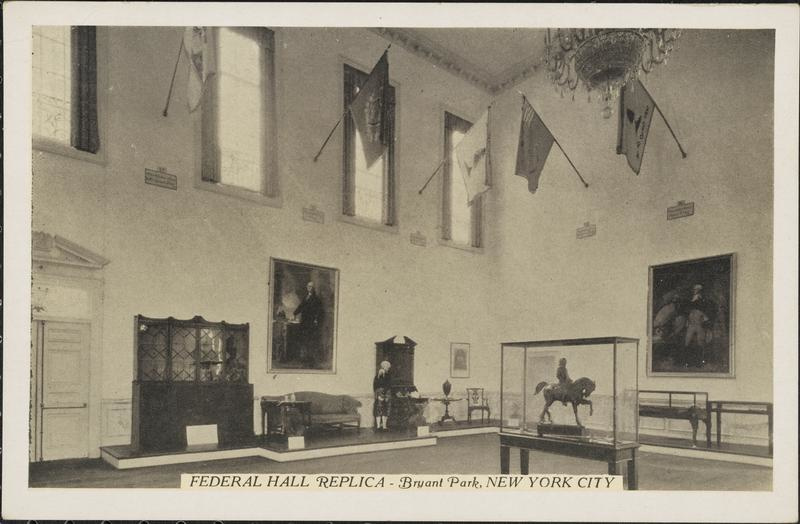

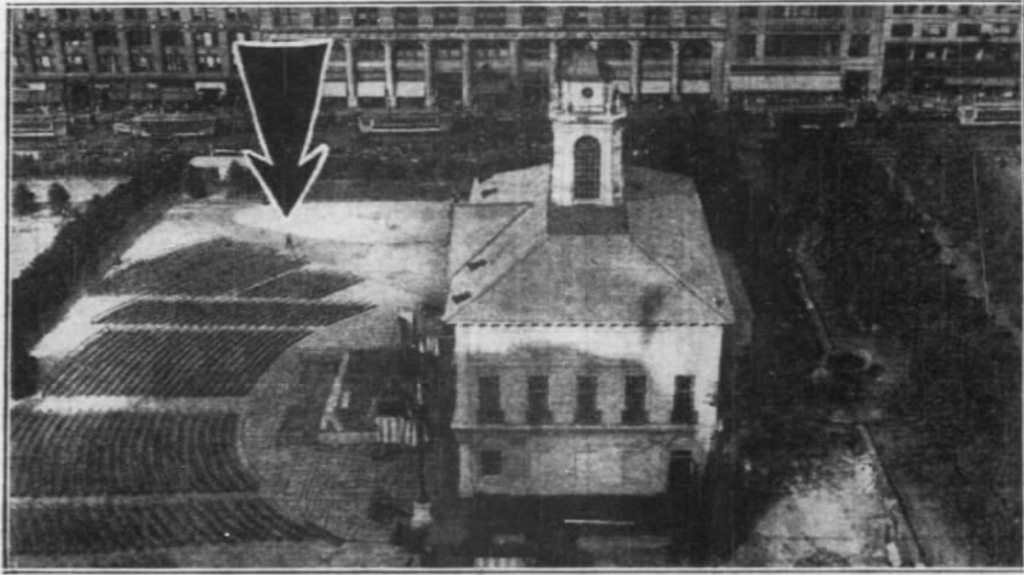

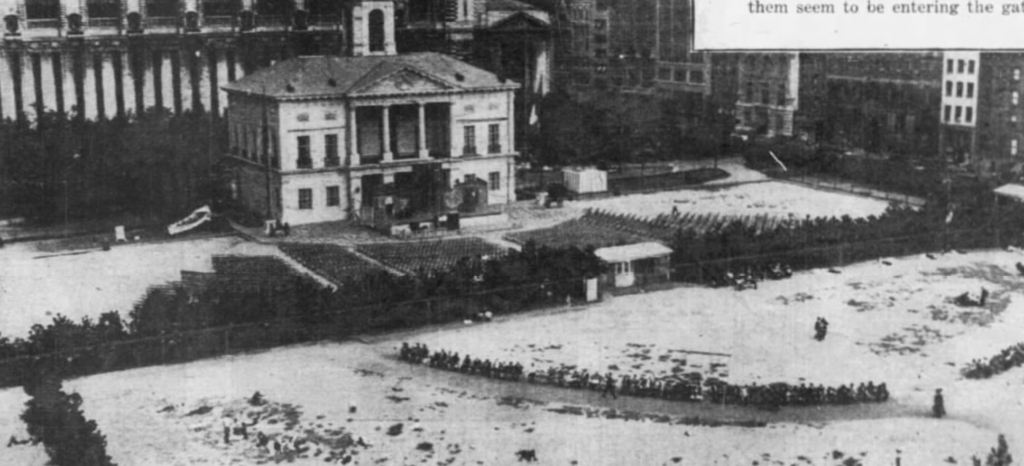

In 1932, the George Washington Bicentennial Planning Committee partnered with Sears, Roebuck and Company to construct a wood and plaster replica of Pierre Charles L’Enfants’s Federal Hall at Bryant Park. The structure was erected to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Washington’s birthday, and to honor his inaugural speech made at Federal Hall on Wall Street on April 30, 1789.

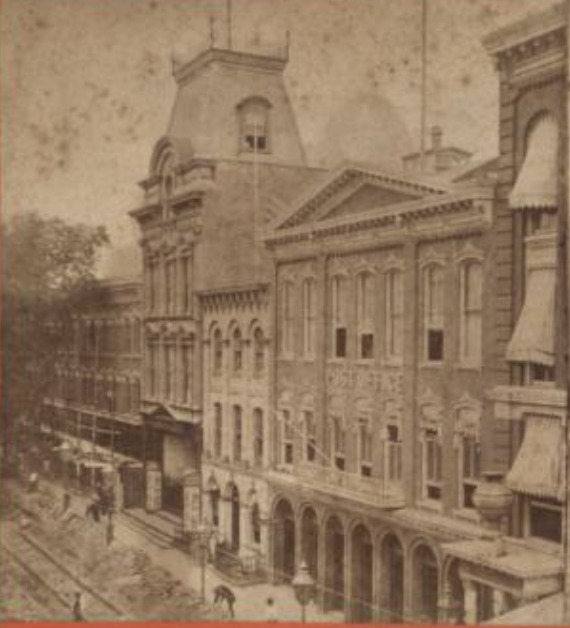

New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses hoped that the replica would attract more people to Bryant Park. The park had been neglected and partly destroyed over the years, due to the construction of the Sixth Avenue Elevated rail in 1878 and later, the digging of the IRT tunnel in 1922. By the early 1930s, the park had become a haven for homeless humans and was considered a disreputable eyesore.

The Federal Hall replica opened to the public on April 30, 1932. Unfortunately, the building did not achieve its lofty goals.

According to the Daily News, few people chose to pay the 25-cent admission fee to view the interior of the building. On some days, there would be only three or four paying customers who could afford such a price. With 33 paid employees required to perform for attendees, there was no way the commission could ever repay the $80,000 it owed Sears when it was only bringing in 75 cents or a dollar a day.

In order to raise much-needed funds, the city’s park department allowed the commission to hold several events at the building, including vaudeville acts and opera performances, courtesy of the Puccini Grand Opera Company. Those efforts were also huge flops with the public.

In August 1932, 50 members of Company A, 16th Infantry, tried to take over the site by setting up tents and talking about military and aerial warfare to anyone who would stop to listen. The city park department saw this as an invasion and ordered the police to kick out the military men.

A reporter for the Daily News questioned, “Having let Federal Hall and hot dog stands into Bryant Park, why should the Park Department complain if the Army, the Navy, the Knights of Columbus and the Ku Klux Klan want to follow along and hold reunions and barbecues there, too?”

To add insult to injury for New Yorkers, more than three quarters of Bryant Park was fenced in and cut off to the pubic, unless people wanted to pay a quarter to get in. (The commission told the city the replica would take up only two percent of the park’s total area, and there was never a mention of an admittance fee when it was proposed.)

It was originally thought the structure would come down when the bicentennial celebration ended on November 26, and that the park would be restored to its former state. But a week before the celebrations came to the end, the special commission had still not decided whether to tear the building down or let it remain standing to serve as a free employment agency for women or a central relief station.

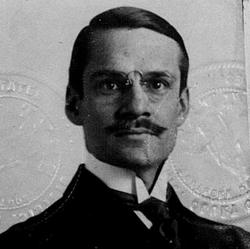

Former New York City Police Commissioner Grover A. Whalen, who chaired the bicentennial commission, explained that several welfare agencies were interested in the structure due to its central location. (This was the era of the Great Depression; there was a great need for services and lodging, with many of the city’s poor living in the Hooverville at Central Park.)

However, Whalen said he could not imagine the Federal Hall being used as a soup kitchen for the needy. He also promised that it would never be used as a lodging place for the homeless (human, that is; the promise apparently did not apply to the Bryant Park cats!).

On November 15, Whalen told the press the commission would make its decision within ten days. He also said he was talking with Mrs. William Randolph Hearst about potential philanthropic uses for the patriotic building.

Ten weeks later, the Federal Hall replica was still standing, with no plans in place for charitable causes.

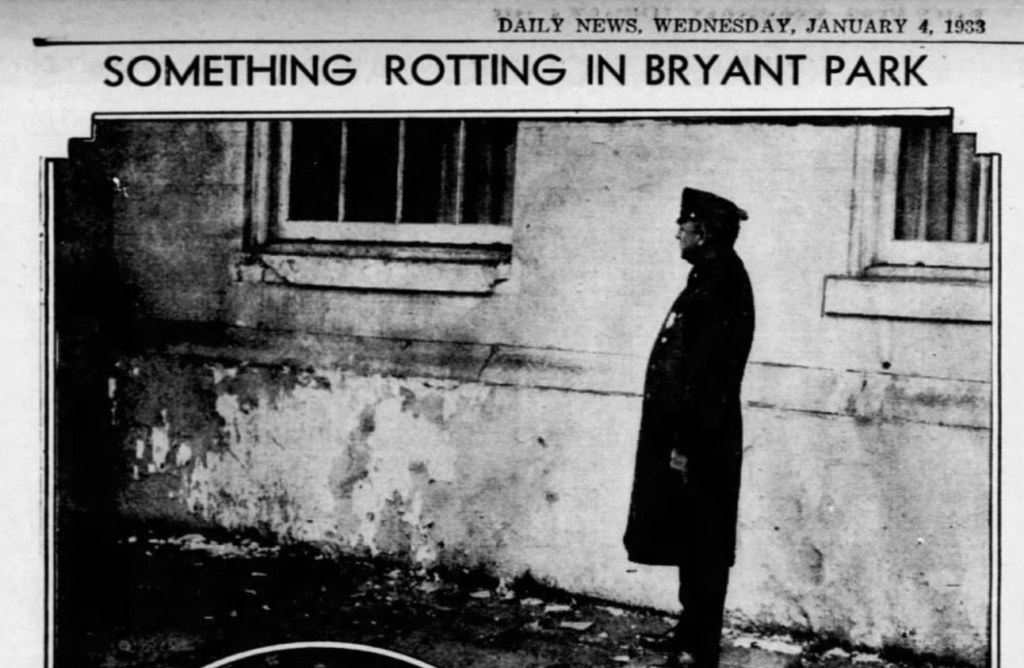

“Forlorn and friendless,” as the Daily News described it at the end of November, Federal Hall was pretty much deserted save for a few alley cats and a flock of pigeons that took up their abode in it.

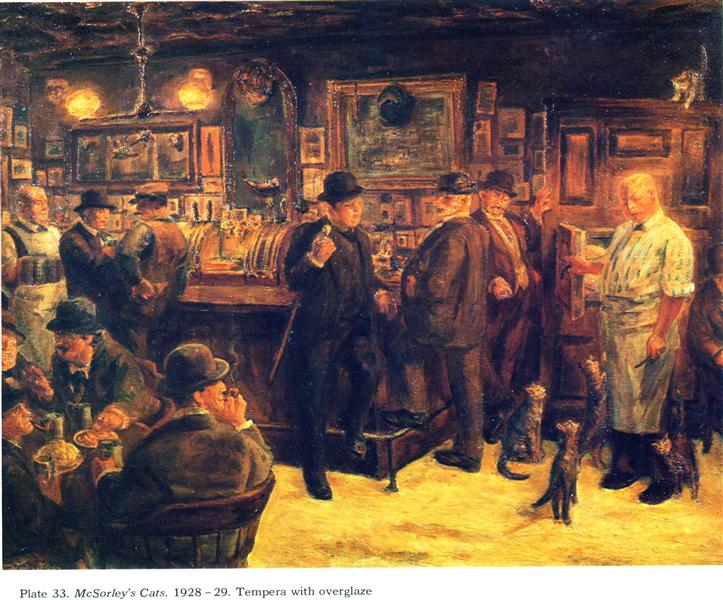

The Felines of Federal Hall

By the end of 1932, what the New York press called an “$80,000 white elephant” was partially boarded up and occupied by only a family of stray cats, who “frisked in and out of holes in its crumbling walls.”

The felines had no difficulty making their way in and out of the structure. Thanks to a December snowstorm, the structure had taken on the appearance of an old Roman ruin, with numerous gaps in the plaster.

Vandals had also lifted off pieces of the Hall to keep as souvenirs (much like they did with the Dewey Arch on Fifth Avenue three decades earlier, which resulted in a cozy plaster home for a mother cat to give birth to her kittens).

In the rear of the ruined structure, which was once a beautiful, grass-carpeted “beauty spot of mid-Manhattan,” were piles of rotting lumber and debris. The cats turned the chaotic mess into their own special playground.

On December 31, 1932, Parks Commissioner Walter Richmond Herrick told the Washington Bicentennial Commission to take immediate steps to remove the flimsy structure from Bryant Park. But by January 2, the first workday of the new year, no steps had been taken to demolish the cats’ home.

Colonel Leopold Phillipp, executive chairman of the commission, promised again that it would be torn down in February. (According to the Daily News, Phillipp wasn’t an advocate for the building’s removal; as he told the press, “We think it is a shame to destroy this beautiful building, which, after all, is in a park that was just a hangout for bums before we took it over.”)

Fortunately for the cats and pigeons, the building remained standing for a few more months, providing them with shelter through the winter.

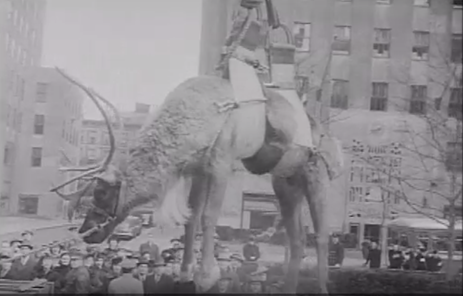

Finally, on March 30, 1933, the city made an official announcement that Federal Hall was coming down. Demolition began in April; by June, all that remained of the structure were the eight steel girders that supported the roof of the building.

Mary Kane and the Bryant Park Cats

I do not know what happened to the cats living in Federal Hall after it was torn down. However, I do know that the stray cats of Bryant Park had a benefactor named Mary Kane.

According to an article published in the Daily News in 1934, Mary Kane was a poor woman who attended to a blind man who operated a late-night newsstand at Bryant Park.

Every day at 4 a.m., Mary would guide the man to an uptown trolley at Third Avenue and 42nd Street. Even in the winter, Mary would often be barefoot and wearing the thinnest of coats.

According to the paper, Mary often lugged a package along while she led the man to his trolley. Inside that package was a stray cat from Bryant Park.

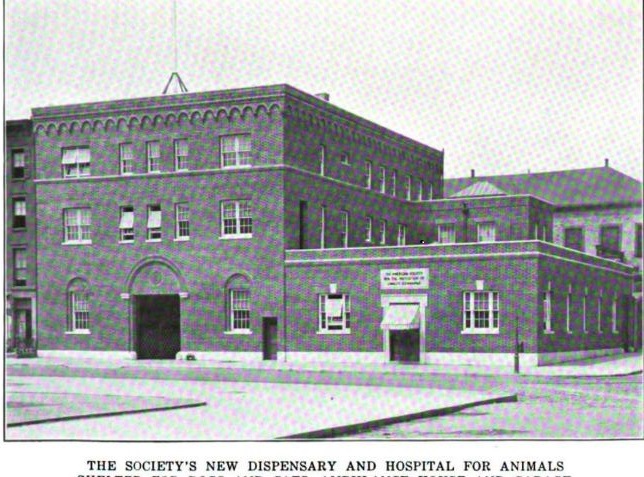

After she saw that the blind man was safely aboard his uptown trolley, she would take another car south to 23rd Street. Then she would carry the stray cat to the ASPCA dispensary on 24th Street and Avenue A.

Sometimes Mary used a cardboard box to carry the cats. Other times, she used a knitted sack made for carrying oranges or other fruit.

Once at the shelter, that cats would be well provided and cared for. If it looked like the cat would make a suitable pet, or if it showed signs of having once been someone’s pet, every effort was made to find it a home.

Mary never received any fame or fortune for saving these cats. Like many women, she felt sorry for the cats, especially those that got all the bad breaks in life.

As the reporter noted, several times a week, for about six or seven years, “Mary Kane, a poor young thing whom the big town has overlooked, has captured a stray cat and taken it to the SPCA.”