Cats in the Mews: March 27, 1904

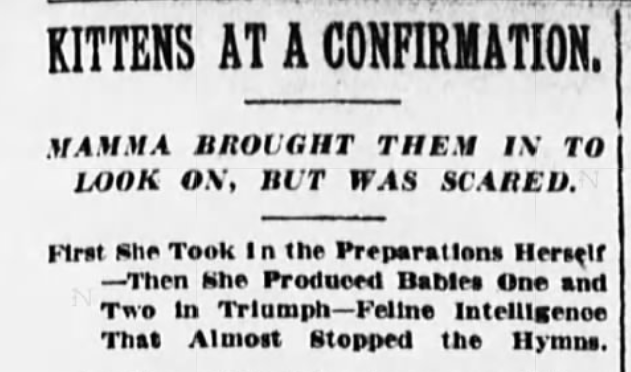

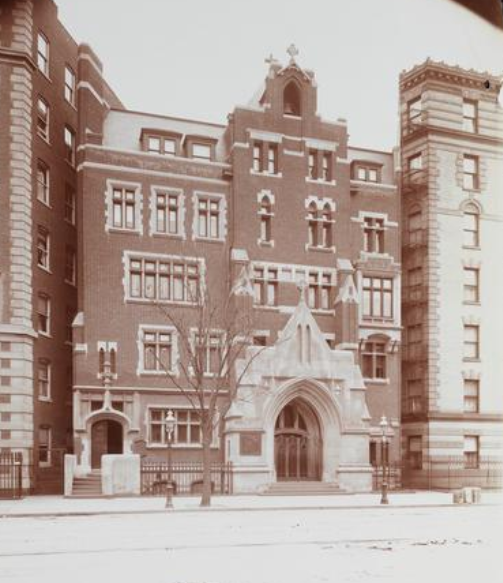

Six months after a brand-new Episcopal Church of the Archangel on St. Nicholas Avenue in Harlem was heavily damaged by fire in 1903, Bishop Henry Codman Potter administered the sacramental rite of confirmation at a new all-brick edifice still under construction. It was the first service held in the new church since the fire.

Because the main body of the church had not yet been completed, the service took place in the congregation’s Neighborhood Guild Hall. The large hall was located in the basement of a five-story rectory and “apartment building” attached to the church proper, and could accommodate 1,200 people.

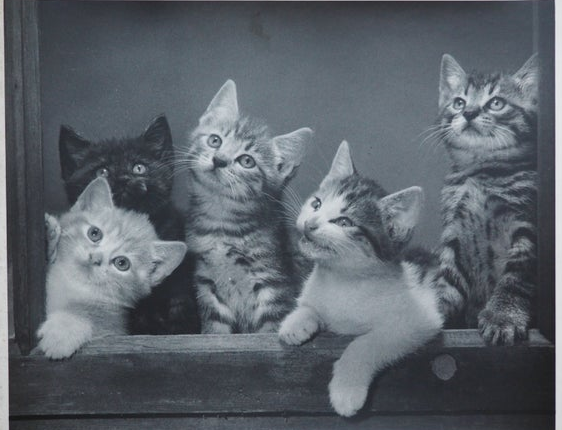

On the day of the inaugural service with Bishop Potter, the hall was filled to capacity. But that didn’t stop a mother cat and her two kittens from squeezing in and attending the service. Apparently, Mama cat believed her two youngsters deserved to be confirmed in the church also.

Mama Cat Presents Her Kittens

According to the New York Sun, lay reader Allen Davidge Marr was just giving out the second lesson when one of the women in the choir let out out a loud cry. The woman was apparently the first to spot a ginger cat, who had been hiding behind Bishop Potter’s chair.

The cat ran into the north choir stalls, then back into the sanctuary, before making her way down the aisle and through the front door. While the younger members of the church attempted to hold back their merriment, Bishop Potter could only suppress a smile as best he could.

The congregation and the choir resumed its singing, but that did not last long. Soon, everyone in the front pew stopped singing. Like today’s “waves” at giant stadiums and auditoriums, the silence made its way pew by pew to the southern end of the large room, until only the members of the choir remained singing.

There, occupying the most prominent place on a platform that was currently serving as the sanctuary, stood the mother cat. She took one look around, and then quickly disappeared. When she returned, she was carrying a wee yellow kitten in her mouth. Everyone in the front pews put their heads in their hands and trembled with suppressed laughter.

Once again, the mother cat disappeared. There was a deep sigh of relief from the north aisle, and the singing resumed.

A few seconds later, Mama cat darted out from behind Bishop Potter’s crimson robe, and then vanished again under the robes of the ministers near the choir stalls. “Then, as the hymn burst forth with renewed vigor, she appeared on the platform exhibiting yellow kitty No. 2.”

The bishop sent a small boy up to the platform to encourage the mother cat to leave. Instead, the little boy grabbed one of the kittens, causing Mama cat to clutch her other kitten and make a made dash across the platform. When she realized her second kitten was missing, she scurried up the north aisle, across the stage, and back over the platform to where she had last seen her little one. A small “meow” coming from the direction of the boy led her to her kitten, which she carried away to safety.

The hymn came to an end and the confirmation service for the 30 young children began–albeit, without the two kittens.

A Brief History of the Church of the Archangel

The Episcopal Church of the Archangel was established as a Harlem mission sometime around 1894 by Rev. Dr. T.M. Peters, the Archdeacon of New York. For some time, services were held in hired rooms; later, the diocese purchased a lot on Harlem Avenue (now St. Nicholas Avenue) at 117th Street for 30,000 and constructed a simple church. The church’s first pastor was Rev. Ralph Kenyon.

In 1897, The New York Times described the Church of the Archangel as follows:

A pretty little church that brightened up Harlem Avenue, composed of vacant lots when it was built, and gave bright promise of welcome to the Episcopalians who should come to live in the neighborhood when that neighborhood was built up. It made no great architectural pretensions. The building is only one story high and simple in its outlines. But there is a touch of stained-glass about the windows and the interior is warm and agreeable in coloring. A very nice little church, indeed.”

Soon after Rev. Kenyon resigned from the parish around 1897, the church fell on hard times. The Roman Catholic Church of St. Thomas the Apostle, which was constructing its own church around the block on 118th Street, purchased the simple church. Reportedly, Father John J. Keogan wanted to prevent it from being purchased by the Salvation Army.

The Catholic congregation held services in the little Episcopalian church until its own edifice was completed. The small church was then used as a school for 900 students, until the building burned down on April 13, 1913.

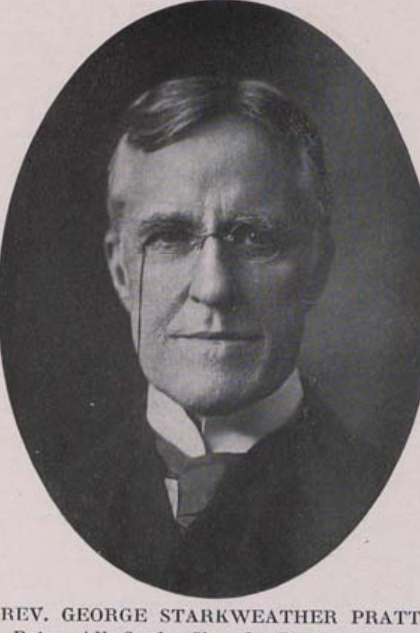

After the Church of the Archangel was sold, Rev. George Starkweather Pratt took over the congregation. The first service under his pastorship took place in the crypt of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine; services were also held in various dance halls in Harlem.

Under Rev. Pratt’s leadership, the parish eventually expanded and prospered as more families moved into the neighborhood.

By the end of 1899, Rev. Pratt had erected a temporary worship hall on St. Nicholas Avenue at 114th Street. One year later, the small hall was surrounded by two brand-new, 7-story apartment buildings. The new apartment buildings — the Warwick Apartments and the Carvel Crown Apartments — created a challenge for the congregation, which had been planning to construct a permanent church on its now sandwiched-in lot.

Enter Janes & Leo, the architects hired to design a new Church of the Archangel. Their solution was to design a combo church and rectory, which had never been done before (at least not in New York City). The newspapers called the design a “novel experiment” in church architecture.

The new structure would be half residential and half ecclesiastical, with a five-story brick structure facing the street and a one-story frame building extending into the rear of the long-but-narrow lot. The structure facing the street would serve as a rectory and apartment building, and the rear of the structure would be the church proper. The entrance to the church would be through a formal church door that lead into a passageway running through and under the home of the rector.

The night before the grand new church was scheduled to open for services, it was severely damaged in a fire of unknown origin.

On the evening of September 27, 1903, Policeman Goodrich of the West 125th Street police station discovered a fire coming from the vestibule of the frame church. As flames pierced the windows and roof, all available fire apparatus above 59th Street were summoned to the blaze.

The heat of the flames burst the windows in the Carvel Court Apartments at 80 St. Nicholas Avenue, causing the sashes to catch fire. An elevator boy ran the elevator up to the top floor to alert residents, and then stopped on each floor to warn everyone to get out of the building.

On the other side of the church, at 92 St. Nicholas Avenue, the elevator boy and janitor alerted residents of the Warwick Apartments. Panicked residents dressed only in night clothes ran into the streets carrying pet dogs, expensive gowns, and other articles of value.

Several people had to be rescued, but everyone survived. Police arrested five suspicious men, but it was later determined that the men were trying to rob the fleeing residents and had nothing to do with the fire. All church documents were lost in the fire.

Recalling the fire and the period in which the congregants had to worship in a dance hall and later at the Constance apartment house on 113th Street, Bishop Potter had this message for the congregation following the cat escapade and confirmation services in 1904:

I am afraid of the tendency which seems to be growing to make a church look more like a music, or dance, or lecture hall. I have no doubt that God hears more prayers in the kitchen and the bedroom than he does in the church, but it is nevertheless true the sacred and impressive atmosphere in a church or cathedral has a devotional influence. The scenery around us is more influential than many of us think.”

On March 14, 1905, the Church of the Archangel merged with All Souls’s Church. Rev. Pratt continued to lead that congregation until his sudden death at the age of 72 in 1920.

In July 1932, the church was the scene of a rebellion, when the all-white vestry announced that the church would be segregated and black congregants, who made up 75 percent of the congregation, would have to worship in separate services. Bishop William T. Manning interceded and demanded that church services be open to all those souls who chose to attend.

I am going to assume that “all those souls” would include cats, too.

If you enjoyed this story, you may also want to read about the mother cat who lived with her kittens inside a church organ in Brooklyn in 1902: https://hatchingcatnyc.com/2020/02/17/cat-family-lived-in-church-organ/