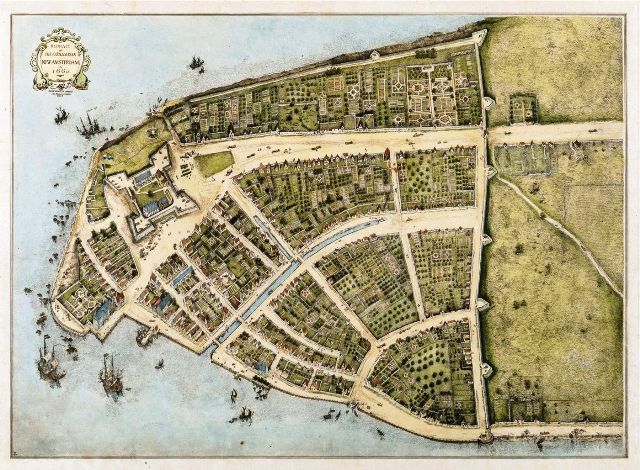

In 1799, the New York State Legislature relocated the Quarantine Establishment of the Port of New York from Governor’s Island to the northeastern tip of Staten Island, in the present communities of St. George and Tompkinsville.

This move to Staten Island was, for all intents and purposes, the start of the 60-year Quarantine War on Staten Island. The “war,” which pitted the local Board of Health and residents concerned about the spread of yellow fever against the Quarantine Commission, was a Not-in-My-Backyard (NIMBY) battle on steroids, with, sadly, vitriol and civil disorder not too different from what we see in our world today.

Joel and Udolpho Wolfe

In 1774, Benjamin Wolfe, a German Jew, emigrated to London. Two years later, he moved to Virginia, where he served under George Washington in the Revolutionary War for seven years. Major Benjamin Wolfe — now a very successful merchant — joined the army again in 1812, taking command of the troops in Richmond, Virginia. He passed away in 1818, leaving a large estate to his seven sons and one daughter.

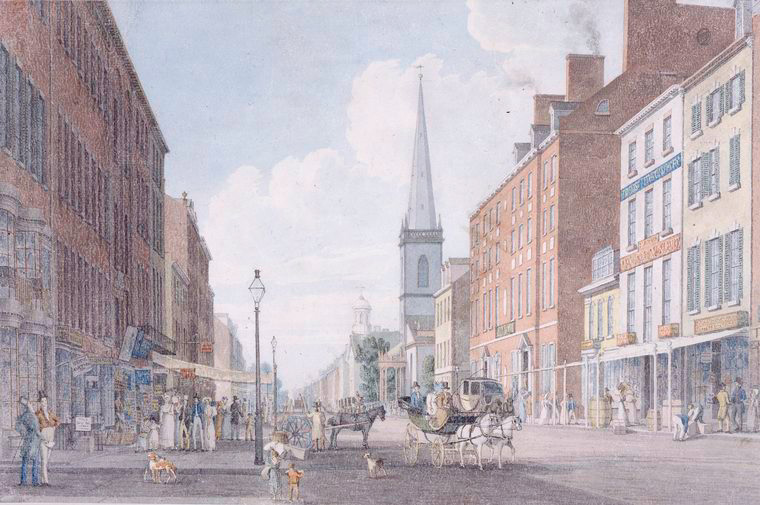

Sometime around 1824, Joel Wolfe moved from his father’s home in Richmond to New York City, where he established a counting house at 109 Front Street. His younger brother Udolpho came to the city two years later and joined Joel as a clerk in the business. By this time, Joel was then largely engaged in the importation of brandy and gin from France and Holland.

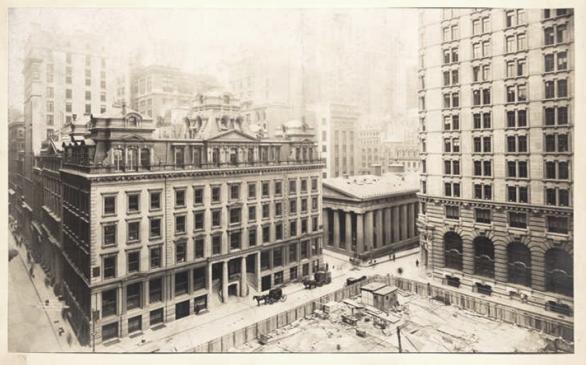

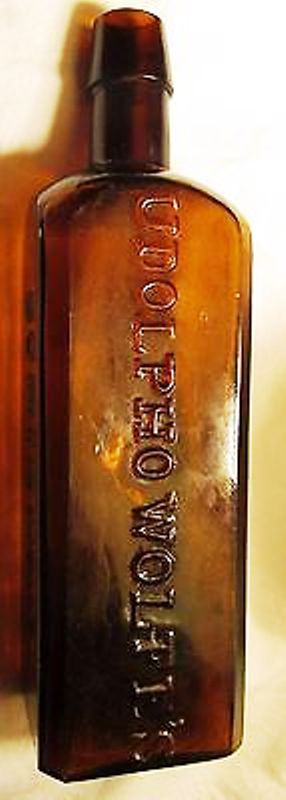

In 1839, Joel Wolfe established the first American-owned distillery in Schiedam, Holland. He also established a warehouse for his liquor business in a brick building at 27 Beaver Street (which burned down in July 1946). Ten years years later, in 1849, Udolpho made some fortunate discoveries that led to the manufacture of the world-famous “Wolfe’s Aromatic Schiedam Schnapps,” which was manufactured at the Holland distillery.

By this time, Joel Wolfe had retired from the liquor business, having amassed a fortune not only in gin but in real estate. In addition to his Manhattan residence at 305 Fifth Avenue — a four-story brownstone with a stable for his horses — Joel owned property at 121 and 124 West Houston Street, six lots in the village of Wakefield, Bronx, and a farm on Seguine’s Point in Prince’s Bay (Westfield), Staten Island, which served as the Wolfe’s country seat.

The Wolfe Farm at Seguine’s Point

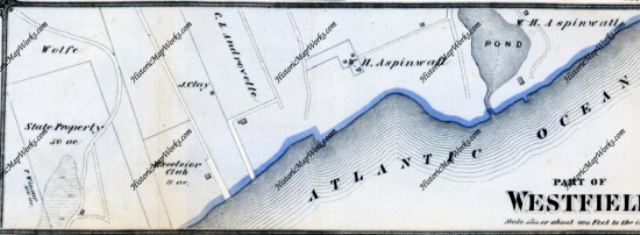

Following his retirement in 1848, Joel Wolfe and his wife, Rachel, spent much of their time at the family’s country seat on Staten Island. The 131-acre farm featured a large mansion house, a farm house, and several outbuildings, in addition to a very large freshwater pond.

The farm was just east of Prince’s Bay Road (today’s Seguine Road) and adjacent to the 140-acre tract of Joseph Seguine, a farmer, oyster harvester, and factory owner who had a dock and palm oil factory (Staten Island Oil and Candlemaking) at the water’s edge.

(The Sequine Mansion, a Greek Revival-style house built in 1838, still stands on Seguine Avenue, as does the Manee-Seguine homestead, built prior to 1700 near Purdy Place.)

In addition to farming, the “retired” Joel Wolfe served on the first Board of Directors of the first railroad on Staten Island, a 13-mile track completed in 1860 that ran from Vanderbilt’s Landing (today’s Clifton Station) to Etingville. (Joel and Udolpho were also accused of being rebels who were loyal to the Confederates during the start of the Civil War, but that’s another story.)

New York State Buys the Wolfe Farm

Back to the Quarantine War…

By 1849, infectious diseases from the Quarantine on Staten Island were epidemic among residents of the surrounding area. A Study Committee recommended that the Quarantine be removed to Sandy Hook, but no action was taken. The tipping point came in 1856, when 11 people on Staten Island died of yellow fever. A more remote location had to be found.

On May 1, 1857, the Quarantine Commissioners purchased 50 acres of the Wolfe Farm for $23,000 and vested the property in the people of the State of New York. Wolfe and his family moved out of the mansion and returned to their city residence (the mansion was going to serve as the residence of the quarantine’s physician). Wolfe put his former steward, Martin Morrison, in charge of the property until it could be fully conveyed to the state.

The Wolfe Farm Burns Down

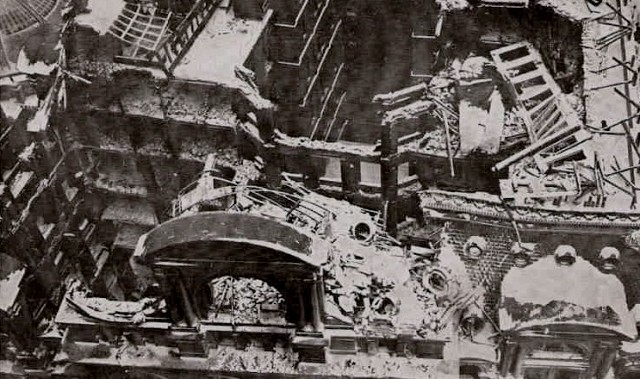

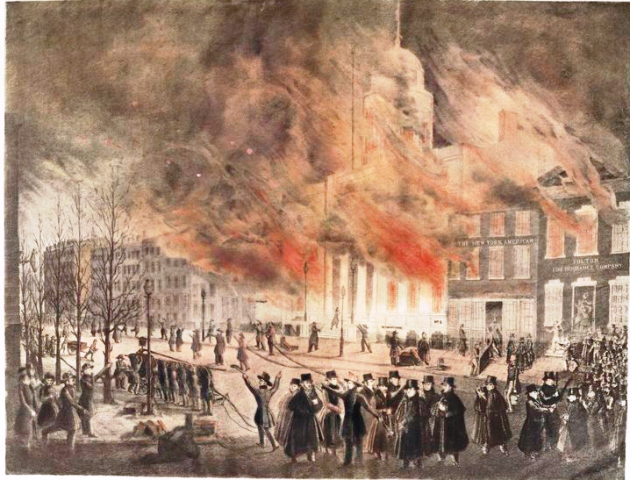

On the morning of May 6, 1857, the Quarantine Commissioners issued an advertisement for the proposal of bids to erect several buildings for housing sick immigrants on the site. The ad enraged the local fisherman and oystermen, who feared that such a facility would contaminate the freshwater pond that they used to wash off their oysters. That evening, just around midnight, about 30 such men burned down one farm building after another in protest of the new quarantine.

They men started with the large mansion, which was occupied by Samuel Fitzpatrick (a family waiter), a young boy named James Murray, and a black girl named Mary Atkinson (possibly a slave; it has been reported that Joel and Udolpho had slaves). According to The New York Tribune, all three were sleeping in the house when the fire started. Fortunately, Mary heard the commotion and alerted the young men, allowing all three to escape by jumping from a second-story rear window.

The mob then proceeded to the two-story farmhouse, which was occupied by Martin Morrison, his wife and two children, a civil engineer, and a young boy hired to pack up the Wolfe’s furniture. Awakened by a flickering light from the flames, Mrs. Morrison alerted her husband to the fire. As the men set fire to the farmhouse, Martin shouted to his children and other occupants to make their escape as the flames closed in on them.

Within a few feet of the farmhouse was a large, nearly new cow barn filled with hay, straw, farming equipment, and two cows. One of the cows escaped but was severely burned and had to be killed; the other cow was consumed by the flames. A stable housing Joel Wolfe’s two horses — one a valuable brown mare — was also set on fire. According to news reports, both horses were led out of the stables safely by Mr. Fitzpatrick.

As the New York Herald reported on May 8, all the arsonists escaped:

At a distance, and within the confines of a wooded space, [the victims] saw the forms of men, gazing upon the spectacle with apparent delight. They laughed mockingly at the condition of the poor people, and then, like evil spirits as they were, disappeared in the darkness of night.

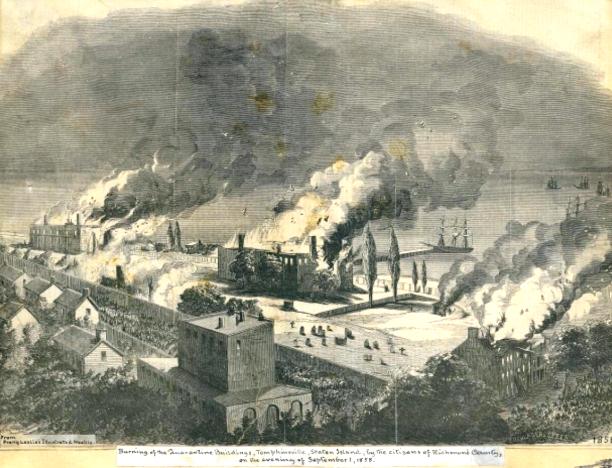

In June, the Quarantine Commission constructed two new hospitals, a wash house, and a small cook-house on about three acres of the former Wolfe Farm, all surrounded by a 10-foot-tall fence. The buildings were all constructed of wood on brick foundations. All of these buildings were set on fire less than a year later on April 26, 1858. No effort was made to rebuild or bring the incendiaries to justice.

Following this second fire, the quarantine station was relocated to Tompkinsville (and later, after mobs burned down those facilities, to Hoffman and Swinburne Islands). The state established a burial ground on the old Wolfe farm site — near today’s Holten Avenue — which it used for the burial of yellow fever victims through 1890. (Apparently, the cemetery was so close to the water that coffins sometimes washed out onto the beach.)

Wolfe’s Pond Park

Joel Wolfe died at his Fifth Avenue residence in November 1880 and was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery. In 1901, his estate sold the remaining 81 acres of the farm at Prince’s Bay. Although the land was sold to a private developer in 1907, it stood vacant, save for a summer bungalow colony, until New York City purchased the land in 1929 for the creation of a public park.