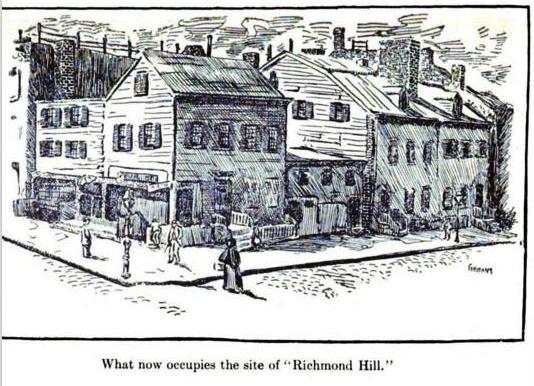

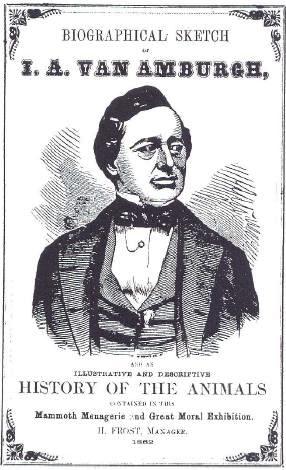

Part 3 of a 3-part story about Isaac Van Amburgh, the Richmond Hill estate in Greenwich Village, and New York’s Zoological Institute in the Bowery

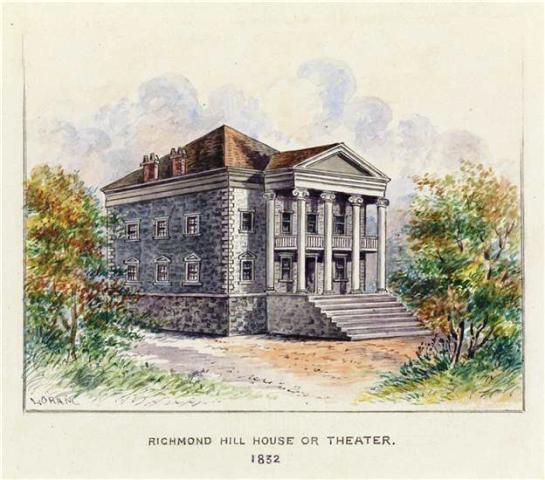

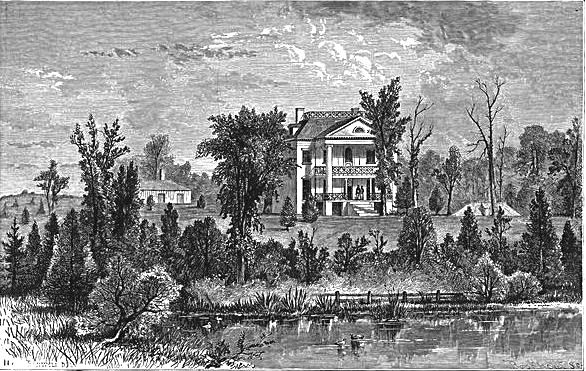

In 1833, Isaac Van Amburgh, aka the Lion King, made his New York animal training debut by stepping into a cage occupied by a lion, a tiger, a leopard, and a panther at the Richmond Hill Theatre in Greenwich Village. Following this appearance, Van Amburgh took his wild animals to the Bowery Theatre at #46 Bowery, which was then under the management of Thomas S. Hamblin. Here, Van Amburgh performed in a play titled The Lion Lord (aka Forrest Monarch), in which he starred with two leopards, a pack of hyenas, and two Bengal tigers.

During the play, Van Amburgh reportedly rode a horse up a high incline, and when he reached the top, one of the Bengal tigers sprung out upon him. Man and beast struggled down the ramp to the footlights in a desperate combat.

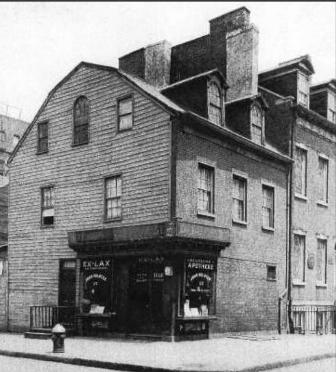

A Brief History of the Bowery Theatre

In the mid-1820s, under the leadership of Henry Astor, wealthy families that had settled in the new ward made fashionable by the opening of Lafayette Street formed the New York Association in efforts to bring fashionable high-class European drama to the new neighborhood.

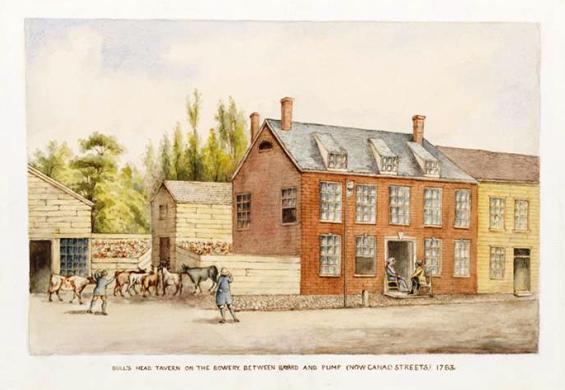

They bought the land where Henry Astor’s Bull’s Head Tavern once stood, occupying the area between the Bowery, Elizabeth, Walker (present-day Canal), and Bayard streets. Then they hired architect Ithiel Town to design their new venue, which opened on October 22, 1826, as the New York Theatre.

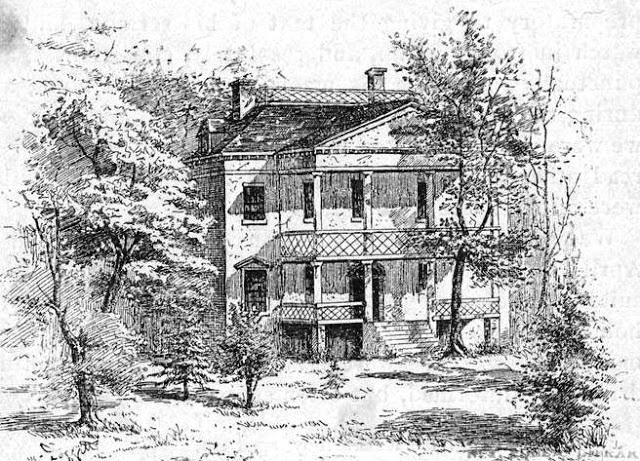

The New York Theatre — later the Bowery Theatre — was built on land once occupied by the Bull’s Head Tavern between Bayard and Pump (now Canal) streets. The tavern opened around 1750 and was famous for serving as temporary headquarters for George Washington in November 1783. In 1813, the tavern relocated uptown to Third Avenue and East 24th Street, where it survived into the 1830s under the ownership of local butcher Henry Astor, patriarch of the notable Astor family.

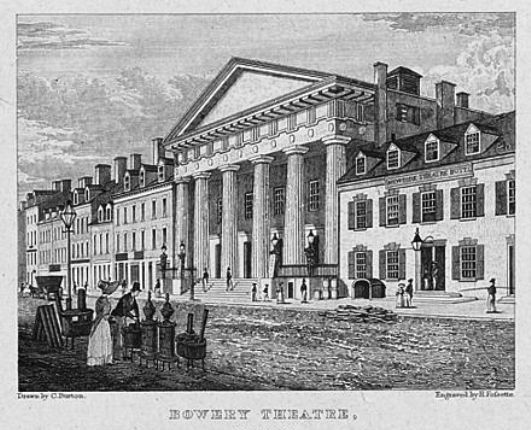

The New York Theatre was destroyed by fire in 1828, but it was rebuilt behind the same facade and reopened under the name Bowery Theatre, shown here. This structure was damaged by a fire in September 1836, and again in 1838, and was replaced by a more opulent structure that opened in May 1839.

Under the management of Thomas Hamblin, who took over the theater in August 1830, large wild-animal acts, blackface minstrel acts, and spectacular productions with advanced fire and water effects featured prominently at the Bowery Theatre (the theater earned the nickname “The Slaughterhouse” during this period).

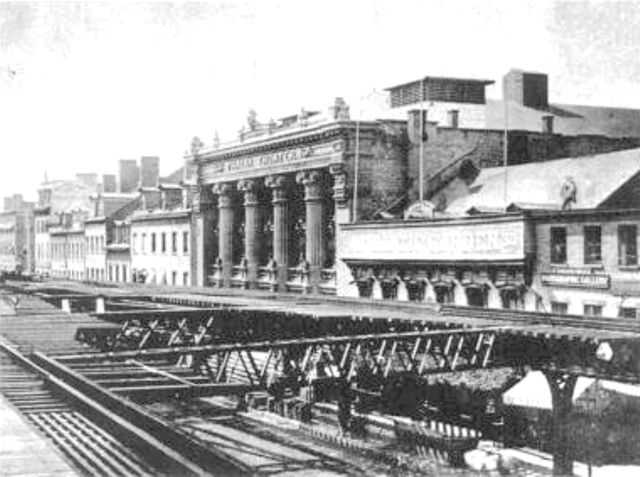

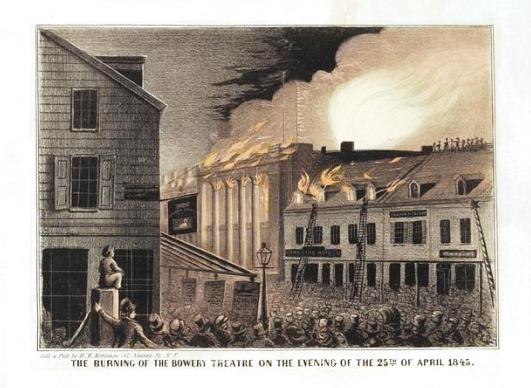

Over the period of 100 years, the Bowery Theatre was damaged or destroyed by fire numerous times. Following a devastating fire in April 1845, a 4,000-seat theater was constructed by J. M. Trimble, pictured above. This structure had four more fires in 17 years, with the final fire coming on June 5, 1929.

By that time, the theater was under Chinese management and was called Fay’s Bowery Theatre. Today #46-48 Bowery is a squat, nondescript building occupied by a popular dim sum restaurant and several apartments in the heart of Chinatown.

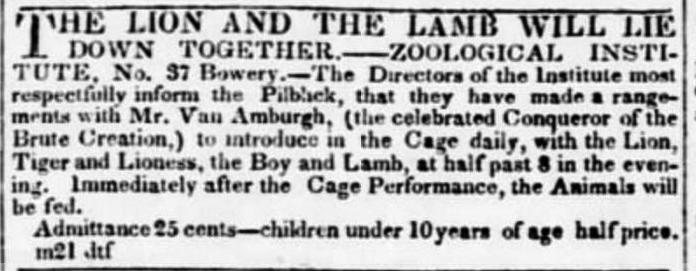

The Zoological Institute at 37 Bowery

Following his stint at the Bowery Theatre, Isaac Van Amburgh moved across the street to #37-39 Bowery, which was then home to a large menagerie called the Zoological Institute. From 1833 to 1838, he performed every winter at the Zoological Institute, and in warmer months, he took his own travelling menagerie on the road.

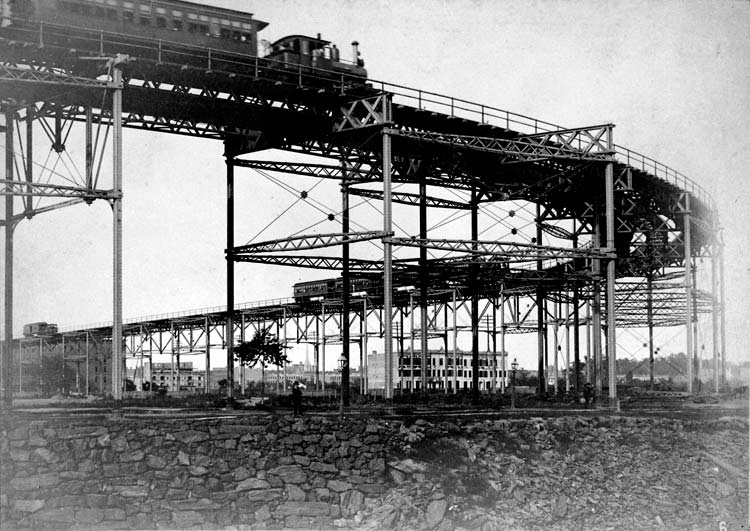

Constructed in 1833 by a group of New York businessmen known as the Zoological Institute or the Flatfoots, the Zoological Institute was a grand structure covering four city blocks. For 50 cents, visitors could examine bears, tigers, monkeys, hyenas, and other animals, all kept in individual cells along a great hall.

The layout of the Zoological Institute was remarkable, even by today’s standards. Each exhibit — like the African Glen exhibit featuring a rhinoceros, elephants, and tigers — had beautiful displays and panoramas depicting the animal’s natural habitat. The floors were constructed at a slight incline leading to a drainage system that ran the length of the hall, which helped keep cages clean and eliminate odor.

Cages were numbered and corresponded to a guidebook for visitors, and the main gallery was illuminated by several skylights in the ceiling (at night, three gas-lit chandeliers illuminated the space). Above the animal floor was an orchestra promenade with a theater-like seating for special events, like lion taming, circus performances, and equestrian shows.

In 1835 the building was modified and renamed the Bowery Amphitheater, where P.T. Barnum landed a job in 1841 as an ad writer, earning $4 a week. The owners changed the name to the Amphitheatre of the Republic in 1842, and in 1844, under the management of John Tryon, it became the New Knickerbocker Theatre.

Over the next 50 years, the structure served as a circus, German-language theater, roller rink, and even an armory for the First and Third Regiment Cavalry. Today the site is occupied by Confucius Plaza, a large apartment complex constructed in 1975.

The Final Days of Van Amburgh and His Menagerie

By the mid-1840s, Isaac Van Amburgh was operating the largest traveling menagerie in England. Twenty years later, he had one of the largest traveling shows in America.

It all came to an end on November 29, 1865, when, at age 54, the brave lion tamer suffered a fatal heart attack at Miller’s Hotel in Philadelphia. Van Amburgh was buried at St. George’s Cemetery in the City of Newburgh, New York, but his name lived on for many more years.

In 1866, a year after his death, Isaac Van Amburgh’s manager, Hyatt Frost, entered into a partnership with P.T. Barnum, who had just lost his American Museum on Broadway to a large fire. The new enterprise at 539-541 Broadway became known as the Barnum and Van Amburgh Museum and Menagerie. Tragically, almost all of the animals and other circus artifacts formerly owned by Van Amburgh were destroyed in a spectacular fire on March 2, 1868.

Van Amburgh’s name continued to be associated with other circuses until about 1922.

Christian F. Greenwald embalmed Dane and other pets at his shop at 2134 8th Avenue. In 1927, when this photo was taken, No. 2134 (2-story building at right) was occupied by a fruit and vegetable market. Next door, in the same building, were a billiards parlor and a meat market. Museum of the City of New York Collections

Christian F. Greenwald embalmed Dane and other pets at his shop at 2134 8th Avenue. In 1927, when this photo was taken, No. 2134 (2-story building at right) was occupied by a fruit and vegetable market. Next door, in the same building, were a billiards parlor and a meat market. Museum of the City of New York Collections