Minnie was just an alley cat — a dusty black and dirty white alley cat, to be more specific. But when she passed away in 1934, she made manly men like Jack Bleeck mourn.

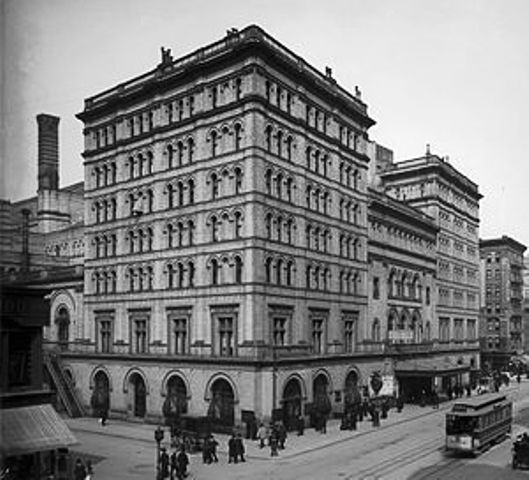

It was a cold November night in 1920 when good luck brought the orphan kitten to the Opera Café at 561 Seventh Avenue (near 40th Street). John “Jack” Bleeck, who had just taken over the place after working as a bartender there for nine years, saw the kitten outside and invited her in.

He was just about to put up a “Help Wanted” sign for a good mouser, so the timing could not have been better.

Jack Bleeck (pronounced Blake), the son of a St. Louis shoe man, left his home city on a freight car sometime around 1900 to find a better life on the east coast. He landed a job making a dollar a day at a cocktail bar in New Orleans during Mardi Gras. After arriving in New York, his first jobs included selling hats and shoes and tending bar at Manhattan Beach on Coney Island.

In 1920, at the start of Prohibition, Jack borrowed some money to purchase the Opera Café and turn it into a speakeasy. Business was brisk, but Jack was no match for the rats and mice who nibbled at his customers’ shoes. A cat like Minnie was the answer to his prayers.

On the night she arrived, Minnie slept well in a warm corner of the basement, her little belly full with food. She immediately paid Jack back by catching a mouse and placing it at his feet the next morning. Within six months, she had caught most of the critters and the rest moved away.

As Jack Bleeck told the press just before her death in July 1934, while wiping tears from his eyes:

Next door to me was a rathskeller featuring a business men’s lunch for 15 cents, including a glass of near beer. No real business man could eat the cheap cuts of meat they served. The meat was so tough it attracted rats and the rats used to burrow through the foundations and sneak into my café looking for a decent scrap of sirloin.

These rats were the biggest and boldest you ever saw. They would stand right up against the bar and gnaw at the shoes resting against the brass rail. My customers stood for this tickling just so long, and then began to complain.

I put 30 to 40 traps around the café, but the rats thought it was a game and came around more than ever. I threw gallons of ammonia into the holes they bored in the walls, but they thrived on that. Altogether I spent $600 on those damned rats and they didn’t have the courtesy to leave me alone.

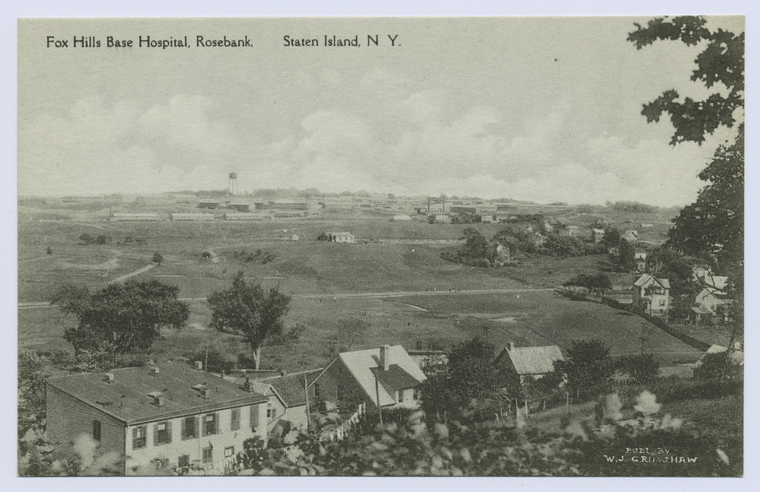

Then, as I say, Minnie walked in out of nowhere one cold, snowy day when I opened the door to oil the lock. Minnie may have come from the [Metropolitan Opera House] but I asked no questions and nobody claimed her. She took immediate possession of the premises and went to work on those rats.

Minnie was made of strong stuff. She’d chase the rats into the holes and then wait three or four hours to get another crack at them. Inside of six months she had cleaned out all the rodents and the survivors never dared come back. It was a tough job. The rats used to gang her, but her paws moved like lightning and she could punch like Dempsey.”

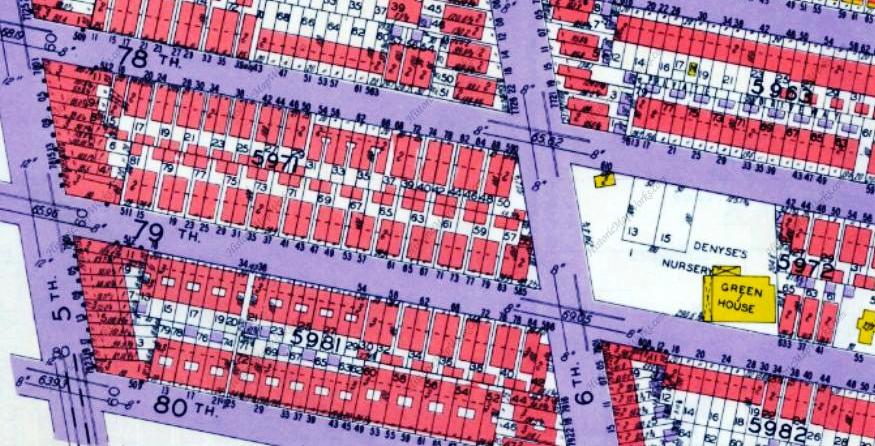

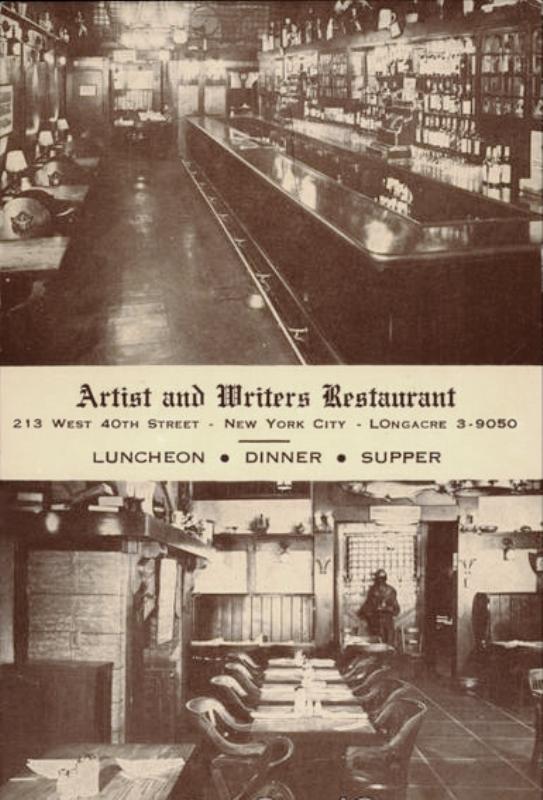

In October 1925, Jack sold the Opera Café and secured a charter from Albany to open a social club in a grimy loft building at 213 West 40th Street, next to the new, New York Herald Tribune building. Called the Artist and Writers Club (apparently only one artist could join), the speakeasy-disguised-as-club looked like and operated like a men’s formal dining club.

Jack was a strict disciplinarian at his club, and he was always present at a central table to keep order. If any of the club’s 6,000 members started singing a loud drinking song or tried to occupy a table without permission, Jack saw to it that he was kicked out. If a wife or girlfriend tried to get in, the entrance was blocked (during Prohibition, patrons had to enter the club through a door inside a warehouse where the Metropolitan Opera stored scenery).

In the early days the Artist and Writers Club attracted opera singers from the Metropolitan Opera House and numerous thespians and stagehands from the National Theatre (later the Billy Rose, and today the Nederlander Theatre) at 208 West 41st Street. Later on, reporters, editors, authors, and press agents from all over the city made the club a favorite literary hangout.

Minnie, Martinis, and Caruso

One of the most famous patrons of the club was the great tenor Enrico Caruso, who would stop by with his friend Antonio Scotti, a baritone, after performing at the Met. Minnie would jump on the bar and arch her back so Caruso could pet her while sipping his Martini.

Although Minnie was the first female ever admitted to the strictly stag club, the feisty feline enjoyed her privileges but did not abuse them. She spent most of her waking hours policing the basement kitchen, which was where she slept in a box filled with sawdust. At 5 p.m. every day she would come upstairs to pass an hour with the men. She loved schmoozing, but she never once meowed or complained in their company.

Over the years, Minnie reportedly had 110 kittens. (I wonder if one of her boyfriends was Tommy Lamb of The Lambs Club?)

According to Jack Bleeck, whenever she was pregnant, members of the club would form a kitten pool and bet on the litter size. Usually she had six kittens at a time, but sometimes she’d have only four or five. The mother cat made good mousers of them all, but none of her offspring ever acquired her social abilities.

After the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, Jack had to change the name of his club to the Artist and Writers Restaurant (I guess he still wanted only one artist to dine there). To the great dismay of his patrons, he also had to allow women. It took Jack 10 months to finally open the door to women, but even then he did his best to make most of them feel quite unwelcome.

The Passing of Minnie

Just six weeks before Minnie died, she gave birth to her final litter of two kittens. Jack Bleeck could sense that she was not faring well after this delivery, so he took her by taxi to the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals. There, she was examined by Dr. Bruce Blair, who told Jack his cat had a tumor in her stomach. He said she was too weak for an operation and could not be saved.

Jack Bleeck said his last goodbye to Minnie on July 20, 1934. He then purchased a plot for her at the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery in Westchester County.

While leaving the hospital for the last time, Jack told reporters, “She has a face like a human being. She looks right up in my face as if to say to me, I know I’m sick and you’re trying to help me.” He raised a finger to his moist eyes and said, “Just some soot in my eye…She’s just a cat.”

In March 1953, Jack sold the business to Thomas F. Fitzpatrick and Ernst Hitz. He died at his home in Manhasset, Long Island, 10 years later on April 22, 1973, at the age of 83.

In 1981, the old loft building was destroyed in a fire. Today a new building houses a Hale and Hearty soup and sandwich shop, and the old employees’ entrance for the Herald Tribune building is the entrance to the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism.