Whence came the elephant? Who knows

The world is dark,

“Dropped from the moon,” some folks suppose

You laugh, but there’s a spark

Of evidence that partly shows

He came not from the Ark;

For, on his flank – the mystery grows—

Is branded “Luna Park.”

— J.A. Tralee, Ireland (published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 6, 1904)

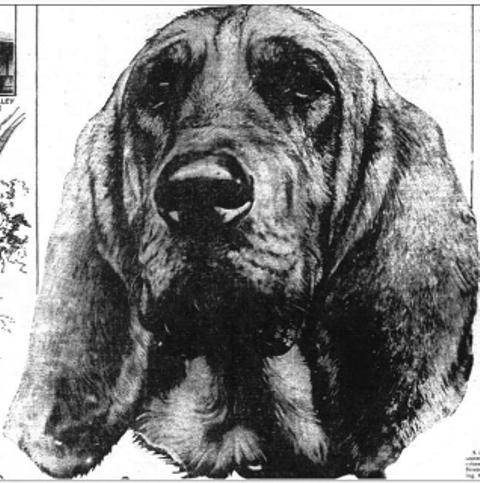

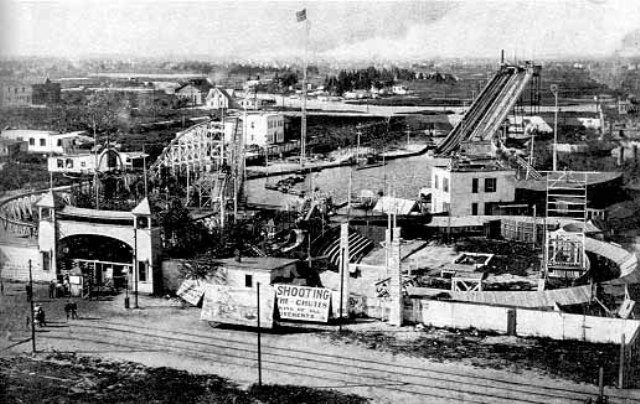

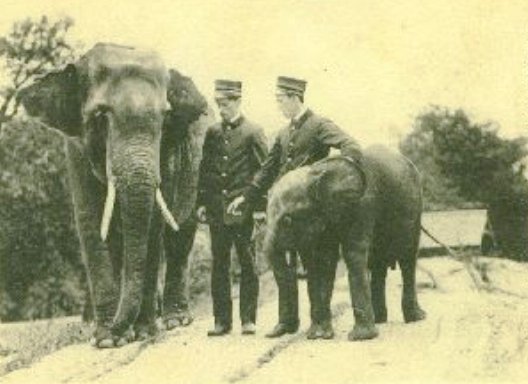

On Friday morning, June 2, 1904, the proprietors of Coney Island’s Luna Park reported that three of their elephants were missing. The two male elephants were found shortly thereafter, but the female elephant, Alice — or Fanny (reports vary) — was nowhere to be found. Alice had gone AWOL.

The proprietors, Frederick Thompson and Elmer “Skip” Dundy, posted a notice in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle offering $100 for any information or for the return of the female elephant. An alarm was also sent out to local police stations when the park employees discovered that she was lost.

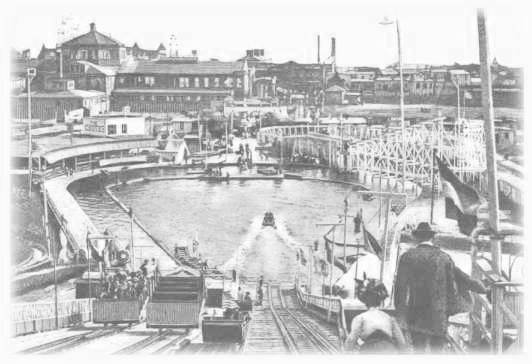

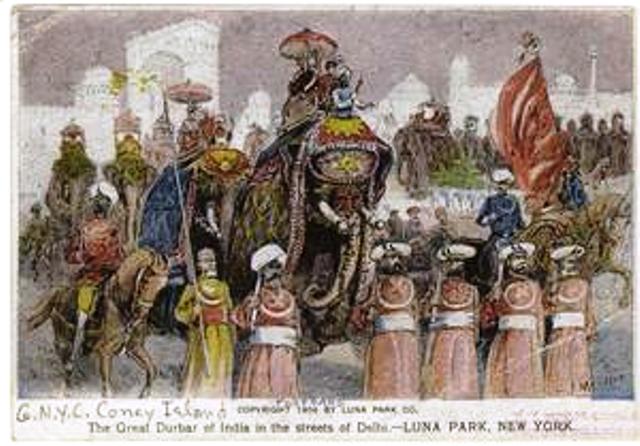

According to published reports, the three elephants were part of the park’s Great Durbar of India attraction, in which hundreds of natives of India and Sri Lanka dressed in colorful costumes and rode through the streets on elephants, horses, and camels. Due to bad weather, the show had been cancelled the night before, and the handlers were careless in securing the three elephants.

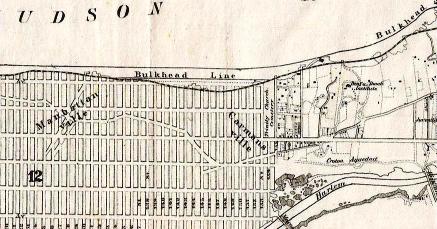

Sometime during the night, the elephants escaped through the rear door of the barn that led to Neptune Avenue and ambled down to Coney Island Creek. Once in the Lower Bay, the two males turned left and swam toward Long Island (Queens); Alice headed for Staten Island. The males didn’t get very far and were captured early Friday morning. Alice kept going.

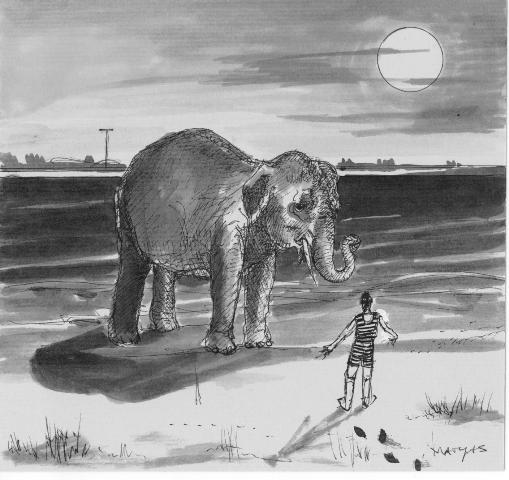

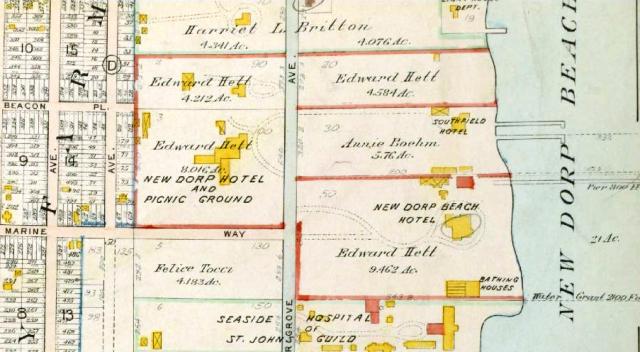

If we are to believe the fishermen who watched Alice swim ashore at New Dorp Beach in Staten Island, then Alice swam about 5 miles across the Narrows from Coney Island.

One of the fishermen, Frank Krissler, of 124 Ogden Avenue, Jersey City, reported that he and his friend had been fishing from their small rowboat about a mile off shore when they heard an unearthly sound and their boat began to roll. It was quite foggy, so they couldn’t see well, but they could tell something very large was headed their way. Soon a huge form appeared off the portside – it appeared to have a giant funnel from which water was spraying up into the air.

“Rhinoceros!” Krissler screamed. “Whale!” his friend cried. The men quickly turned the boat around and started to row as fast as possible toward shore. The elephant followed in hot pursuit.

When they arrived back on shore near Ed Hett’s New Dorp Beach Hotel, the elephant lumbered out of the water and followed them up the beach.

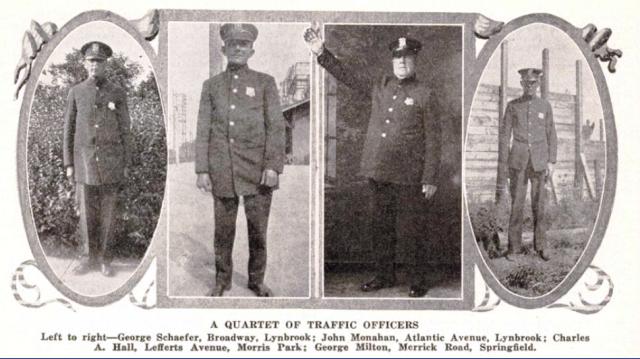

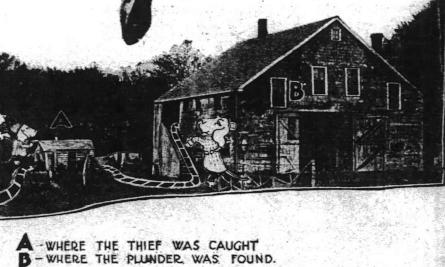

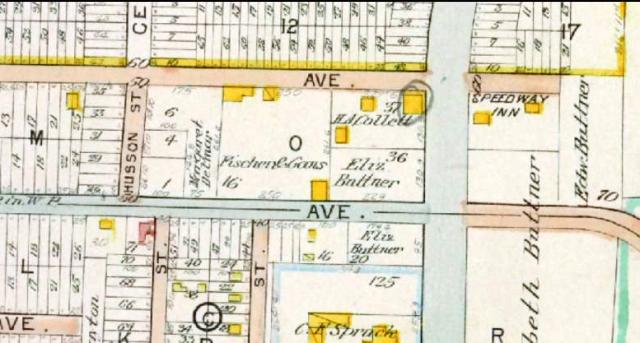

Soon two more fishermen and Patrolman O’Rourke from the New Dorp police force arrived, and the men used ropes to create a lasso. They swung the lasso around the elephant’s tusks and led her toward the carriage shed behind Adolf Eberle’s Speedway Inn in Grant City, where Patrolman O’Rourke knew he could keep her until the police decided what to do with the elephant.

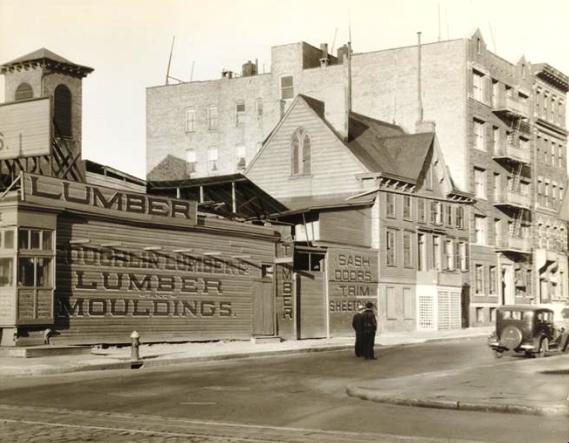

During the long walk to Grant City, Alice reportedly stopped in front of a grocery store to eat a wagon-load of vegetables and take a few gulps from a horse trough. When the group reached the Speedway Inn at Southfield Boulevard and Franklin Avenue (today’s Hyland Boulevard and Bedford Avenue), Alice reportedly pulled up a couple of trees in the yard and yanked a few planks from the porch before entering the carriage shed.

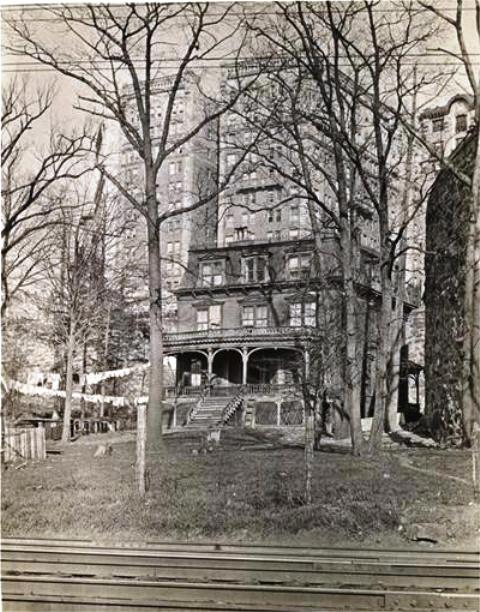

Later that day, more police arrived and Alice was taken to the horse stables of the mounted police on New Dorp Lane and 8th Street. There, she was “charged” with vagrancy.

Hundreds of people gathered in front of the green-terraced station to see the very large prisoner. It was the biggest catch the police of New Dorp had ever made, and as one officer said, “Press agent or no press agent, we got him, and we are going to keep him till a bondsman shows up.”

The officer was making reference to the popular belief that Alice was part of a publicity stunt orchestrated by an over-imaginative press agent for Luna Park. (In fact, two years later, a reporter for Success Magazine claimed that Fred Thompson hired a furniture van to cart the elephant through Brooklyn, across the Brooklyn Bridge, through downtown Manhattan, and then on the ferry to Staten Island. Once near shore, Alice was released into the water.)

A Brief History of the New Dorp Mounted Police

When Alice made her grand appearance on Staten Island, the borough’s mounted police force was fairly young – seven years young, to be exact. It’s no wonder Alice the elephant was the biggest and most exciting event the police had ever experienced.

In 1867, legislation placed Staten Island within the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police Department of New York City. Three years later, another law was enacted that made Staten Island a separate police district under the control of three commissioners. William C. Denyse of Middletown, Abram C. Wood of Castleton, and Garret P. Wright of Northfield were appointed to the Board of Police Commissioners, with Wood elected president.

The incorporated villages put in their requests for police officers as follows: Port Richmond, 7; New Brighton, 7; Edgewater, 14; Tottenville, 2. A police station was established opposite Veterans Park in Port Richmond, in one of the many buildings on Staten Island owned by former Chief Engineer John Decker of the old volunteer fire department of New York City.

In 1883, the department attempted to establish a mounted unit. Much to the public’s dismay, the men were not accustomed to the saddle and the experiment failed. Two years later, however, the Richmond County Board of Supervisors approved the Board of Police Commissioners’ request for an appropriation of $6,000 to supply horses for a mounted squad to patrol the country districts.

The squad had 10 men, including patrolmen John Moore and George Wilson and eight other men who had just been appointed to the force. The men were fitted in a cavalry uniform and drilled by Sergeant Thomas Higgins of the Sixth United States Calvary. Twelve horses were purchased and named after the governors of New York: Morton, Flower, Hill, Cleveland, Cornell, Robinson, Tilden, Dix, Hoffman, Fenton, Seymour, and Morgan.

Alice Goes Home

Many hours after Alice arrived at the police stables, Pete Barlow (aka the Coney Island Elephant Man) and two men from the India attraction at Luna Park showed up and convinced the police that Alice was one of six elephants from Luna Park. They paid a large fine and lead the elephant away down the Boulevard toward the St. George Ferry landing.

After walking about six miles, the group met up with a large horse-drawn wagon that had been summoned from Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. Using hay and apples to lure her, Barlow led Alice into the wagon, which then proceeded to the ferry. Upon arrival in Manhattan, the wagon took Alice down South Street and to the Brooklyn-bound ferry. Once in Brooklyn, the group made of the rest of trip by foot and hoof back to Coney Island.

With Alice safely back at Luna Park, Frenk Kissler the fisherman told the press he was going to collect the $100 reward that was due him.

Incidentally, four years later Alice made the news again, this time when she went on a rampage at the Bronx Park Zoo and “locked” herself in the Reptile House. She had been given to the zoo in 1908 to be a mate for Gunda, the zoo’s first Indian elephant, and it was hoped that some baby elephants would keep her busy and distract her from trying to escape.