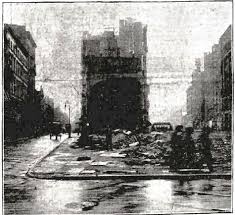

A slice of the block bounded by Mulberry, Houston, Crosby, and Bleecker Streets has been torn away for the Elm Street (Lafayette Street) lengthening. By rare good fortune this demolition took the course of the little slum… It razed every vestige of the slum, leaving only a broad street, with a semi square where Bleecker Street and Mulberry Street meet it, and Cat Alley, with all its turbulence, its crime, its police record, and, it must be confessed, its picturesqueness, is now only a name. — The New-York Tribune, July 30, 1899.

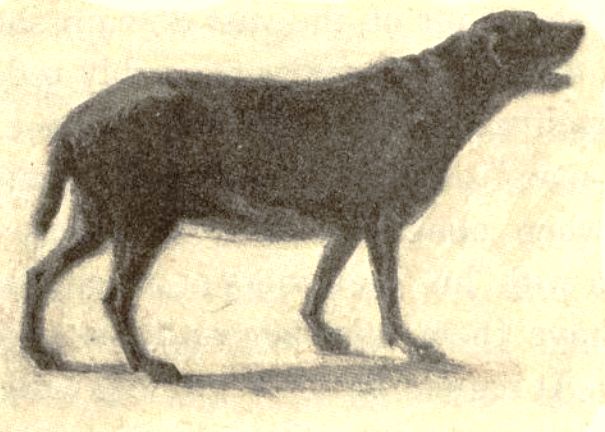

Trilby was just a scared little puppy when she first appeared on Mulberry Street in the winter of 1895. She had run down the street at top speed with a tin can tied to her stump of a tail and the nasty little boys of the Mott Street gang in pursuit.

Seeing a narrow opening between two buildings on Mulberry Street, she darted through the gap and found herself in the confines of Cat Alley.

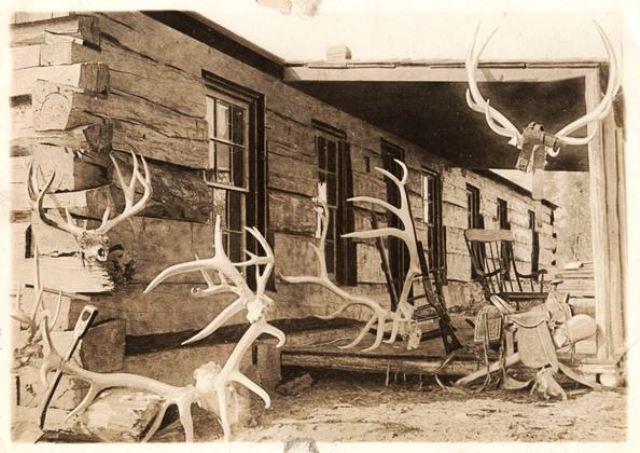

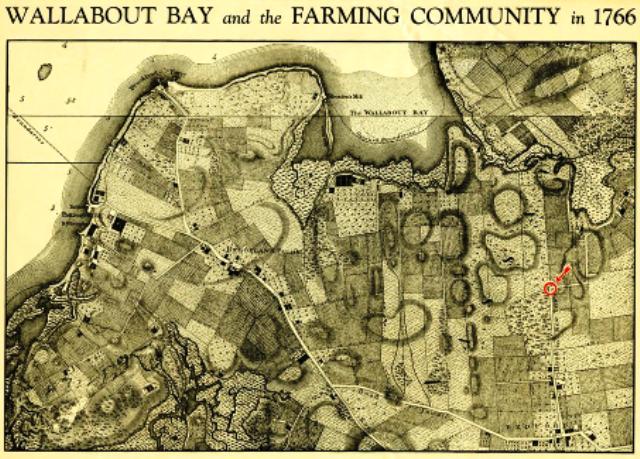

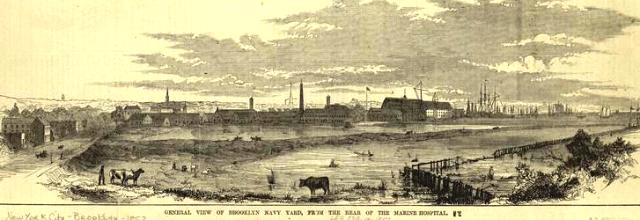

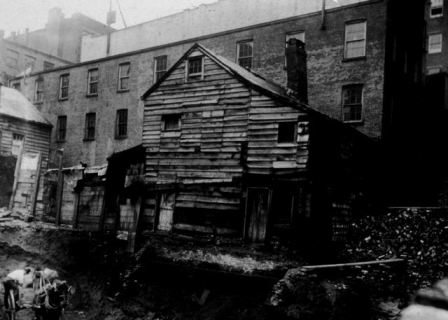

Cat Alley was not really an alley but rather a row of four or five eighteenth-century frame tenements in a back yard nestled between Mulberry and Crosby streets, midway between East Houston and Bleecker.

Cat Alley was also not home to many cats, albeit quite a few strays did find their way into the yard.

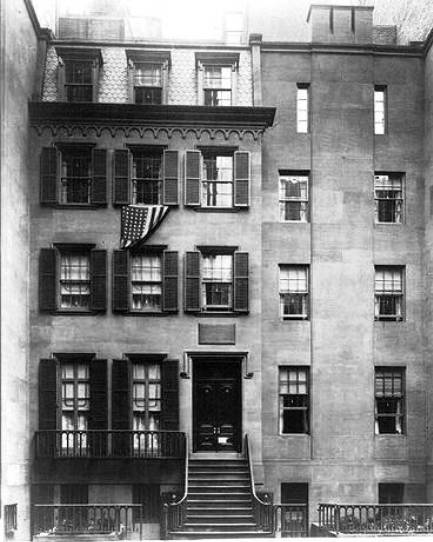

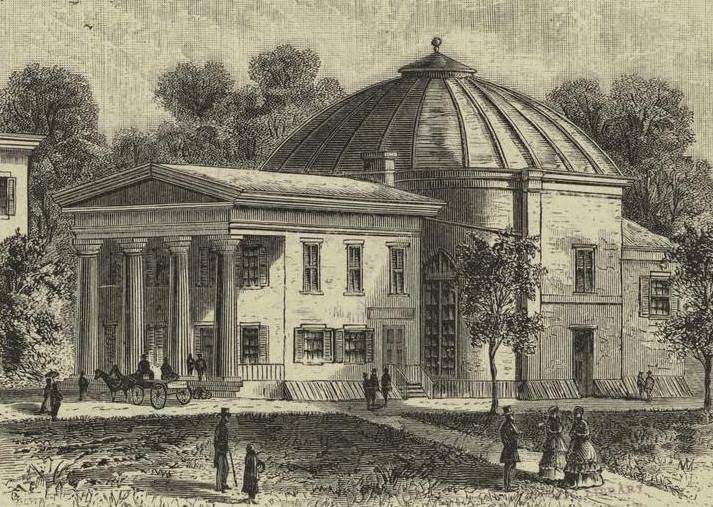

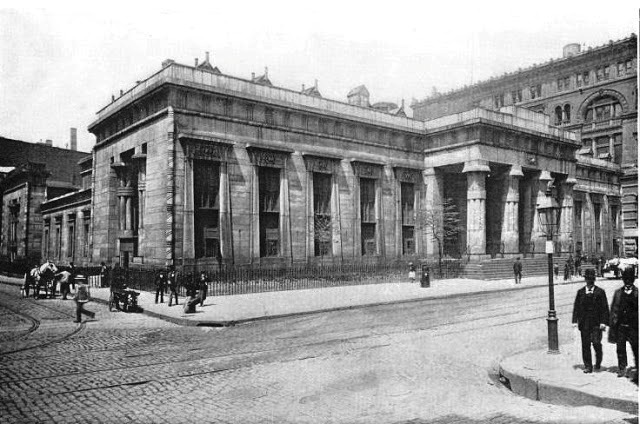

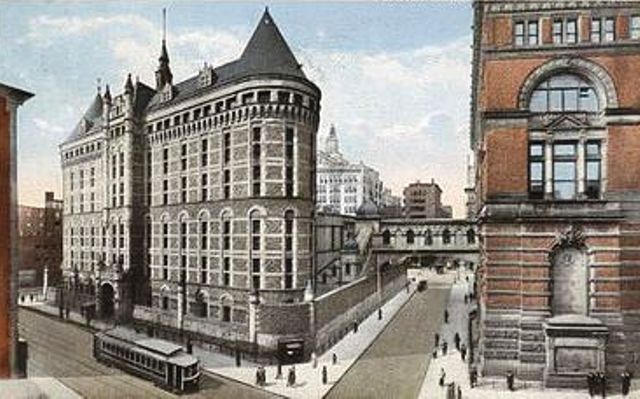

Access to the yard was via a three-foot-wide passageway between the front houses at 301 and 303 Mulberry Street, which were owned by New York City Comptroller Richard Alsop Storrs. Directly across the street from Cat Alley was the New York Police headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street.

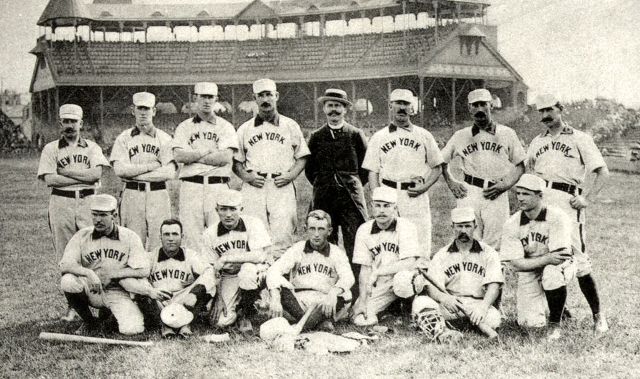

The tenement houses of Cat Alley had once been rather stylish – in fact, one of them had been the parsonage of the church at 307 Mulberry (the San Salvatore Church at this time). In 1897, the front houses were occupied by newspaper offices for the reporters who covered the police and crime beat. The cramped and squalid back houses of Cat Alley were home to Irish and Italian immigrants.

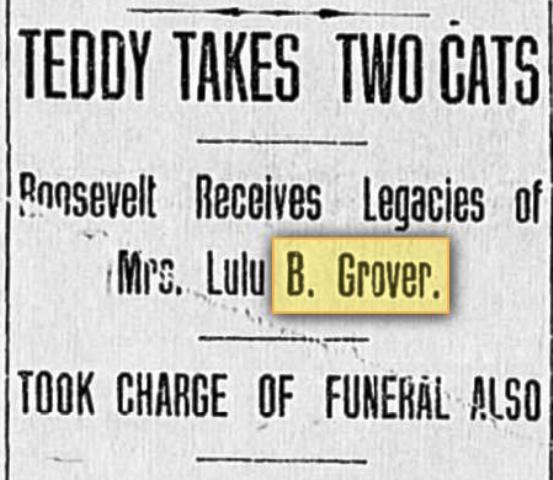

Many of the policemen and reporters stationed at headquarters — like the renowned author and photographer Jacob A. Riis of The New York Tribune — were friends with the residents of Cat Alley. On hot summer nights, they’d all sit around and drink beer or lemonade and listen to music from the accordion players. Most of the families got along okay, although like any impoverished neighborhood, Cat Alley certainly had its share of crime.

From the moment she entered Cat Alley, Trilby was the alpha dog — and the only dog — among all the alley cats who rummaged through the garbage cans and all the reporters who took their daily walks in the yard. She’d spend her time wandering from one newspaper office to the other, poking her head in each doorway looking for some attention.

If the reporters were too busy, she’d head over to police headquarters, where she would ride on the elevator and get off at each floor to visit the police chief and all the commissioners.

On slow news days, Trilby would hang out with the reporters or the kids on the stoop and sing. She could sing only one note, but what she lacked in range she made up in volume. Surrounded by her humans, she would point her nose toward the sky and howl “woe is me” until laughter would drive her away to some hiding spot in one of the newspaper offices, from which she’d refuse to come out.

One time, shortly after she arrived, Trilby ate about two pounds of meat and went running up and down the street barking and howling. She ran between the Gilligan homestead and John Sonntag’s liquor and cigar store at 40 East Houston Street and got stuck.

After about two hours of trying to get her out, a reporter took off his coat and vest and dove between the two walls, emerging on the other side with Trilby in his arms.

Another time, Trilby was at risk of being killed by a gang called the Midnight Marauders of Mulberry Street. These young men, who made their headquarters in a cellar in Cat Alley, created an execution device out of a soap box covered with a piece of glass and attached to a gas jet with rubber tubing. They would put the alley cats and even people’s pets in the box and kill them.

The police started patrolling more heavily, which stopped the killing. Residents of Cat Alley also said they would execute the Marauders themselves if any more of their cats disappeared.

About six months after she came to Mulberry Street, Trilby was run over by a horse-driven wagon while chasing little Katie Gilligan. Her two hind legs were badly injured by the wagon wheels.

A good Samaritan brought Trilby to one of the newspaper offices, and the reporters summoned a vet. Some of the children offered to donate their pennies to help pay for her medicine.

Barney the Cranky Old Key Man

Barney the Key Man, born Michael Coleman, was a Civil War veteran who lived in a decrepit attic on the third floor of an old frame tenement house in Cat Alley. The neighborhood kids called him Barney Bluebeard because, like Bluebeard of the seventeenth-century French folktale, he supposedly detested women, was always crabby, and had lots of keys. They’d get in his face and shout “Barney Bluebeard!” and then run away and hide in trembling delight as he leered and shook his key ring at them.

Born in Ireland, Barney supposedly came to America with an older brother when he was 10 years old. He served three years as a private with Company H of the 23rd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers — the Irish Brigade — in the Civil War, and was wounded two times during the Battle of Lexington. Before moving to New York sometime around 1888, he lived at the National Home for Disabled Volunteers in Virginia.

Over the years, as cobwebs and dirt accumulated in his room, neighbors told tall tales of Barney’s fabulous wealth, which they said he had concealed in cracks in the walls. In truth, Barney was reportedly receiving a veteran’s pension of $8 a month, but he never showed any signs of spending it — save for the dollar he would always give at the early mass on Sundays. The alley residents, however, loved to think that they had their very own miser with a hoard of cash stuffed in the garret roof.

The End of Cat Alley

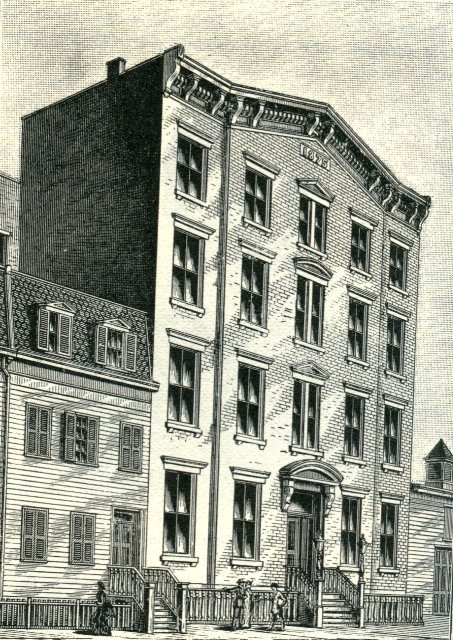

In July 1897, a man from the Department of Public Works handed a resident named Mrs. Finnegan an eviction notice. The notice said that everyone in Cat Alley had to move out by the last day of July. The city had approved a plan to improve Elm Street by extending it south from Lafayette Place (then one block south of Astor Place) and combining it with the roadbeds of the former Marion and Elm Streets. The plan necessitated the demolition of Cat Alley and the Church of San Salvatore.

By the end of July, almost every resident of Cat Alley had packed up and moved. Even Trilby moved out, apparently adopted by the Gilligans or another family from the neighborhood. The buildings were sold at auction for $30 and prepared to be torn down. Still, Barney refused to go, for fear that if he changed his address, his monthly pension would be lost forever.

As workmen began tearing down Cat Alley for the Elm Street extension in November 1897, Barney continued to stand his ground. All around his attic home, he watched the structures come down.

By March 1898, the only way he could get into his house was by going through the New York Herald’s office at 301 Mulberry Street and climbing over a mountain of loose bricks to an attic window. There was also nothing left of Cat Alley but bricks and dismantled frames — and old Barney.

Although the contractor saved Barney’s building for last, he couldn’t hold out anymore. The first thing the workers removed was the attic roof. Then the workers moved inside, where they found a smoke-filled, dusty lair filled with cobwebs. The only furniture consisted of a broken stove, a bedstead, and two chairs.

On Barney’s last day in Cat Alley, a reporter from the New York Tribune climbed up the pile of bricks to visit him in his attic home. He found Barney removing about six locks and bolts from the door. “‘Tis a bad lot they have around here, and they always try to get in, thinking I’ve money,” Barney told the newsman.

As the reporter watched, Barney put all his possessions in a dilapidated iron padlocked trunk and climbed out onto the pile of bricks that covered the front of his house. He brought his trunk to the janitor of the front house and went out to seek new lodgings. “Sure, I don’t know where I’ll go, but I’ll find a place somewhere,” he said. “‘Tis a good place to get away from, after all.”

One Sunday afternoon in May 1898, Trilby came walking down Mulberry Street. She made the rounds of the newspaper offices, waiting patiently until everyone had spoken to her. From that point on, she started to appear every Sunday and holidays for another year or so.

I don’t know where Barney ended up, although it was reported that someone from the Grand Army of the Republic had come around to make arrangements to move him back to the home for disabled veterans in Virginia.

In 1905, the Board of Alderman adopted a resolution introduced by Alderman T.P. Sullivan changing the name of New Elm Street and Elm Street, to Lafayette Street. A small section of the original Elm Street near City Hall still exists today as Elk Street.