There was a time, before the sparrows arrived, when residents of New York City could not stroll through one of the city’s many parks without confronting what The New York Times called “the creeping and crawling abomination known as the inch worm.” The parks were infested with the tiny worms, which not only devoured tree leaves and shrubbery but had a nasty habit of swinging from branches and crawling down people’s shirt collars.

Having heard that the house sparrows of European cities were helping to control insect infestations, a group of prominent New Yorkers, including dry goods merchant Alfred Edwards, imported eight pairs of sparrows from England in 1850.

These pairs were brought to the Brooklyn Institute, where they were cared for and housed in a large cage during the winter months. The sparrows were released in the spring of 1851, but they all died before they were able to breed.

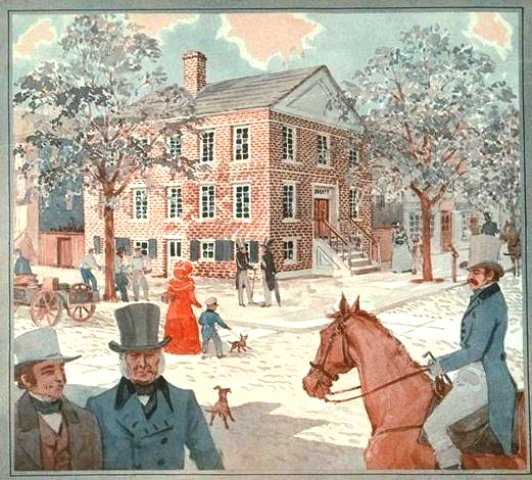

In 1853, Nicholas Pike, the director of the Brooklyn Institute, traveled to Liverpool to collect more insect-eating birds. He purchased about 100 house sparrows and song birds, and shipped them back to New York on board the Cunard steamship Europa. After 11 days at sea, half of the birds were released at the Narrows tidal straight, while the other half were taken to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

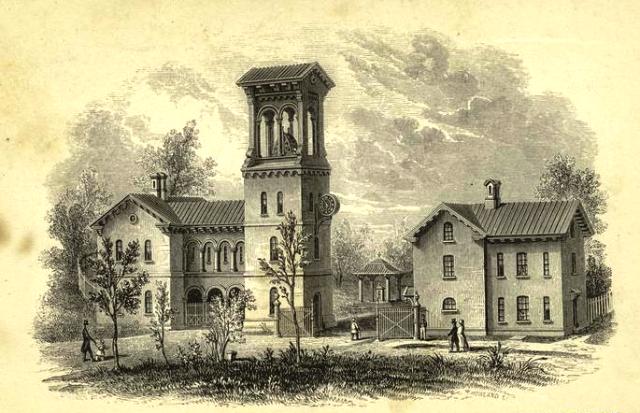

These 50 birds were originally kept in the cemetery’s bell tower, but they didn’t seem to thrive there, so Brooklyn Institute trustee-librarian John Hooper brought the sparrows to his house for the winter. In the spring of 1853, the birds were released into the cemetery, where a man was employed to take care of them.

This second wave of sparrows thrived in their new surroundings at Green-Wood Cemetery, and over the years, several more shipments of sparrows were delivered and released in the cemetery as well as in Central Park. While some considered the sparrows to be a loud nuisance, others were pleased that the birds were feeding on insects and inchworms.

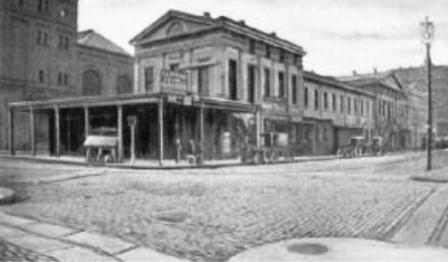

On April 14, 1866, about a dozen English sparrows arrived in Union Square at 14th Street and Broadway. It was thought that the birds had come from either Stuyvesant Square or from a private house at the corner of Fifth and 29th Street.

But other sources report that Director William Conklin of the Central Park menagerie had freed 18 pairs of sparrows in the spring of 1865, with 6 pairs going to the Trinity churchyard, 6 pairs to Washington Square Park, and 6 pairs to Union Square. At the time, Conklin said he thought he was opening a fountain of blessings on the country.

The Sparrow Cop of Union Square

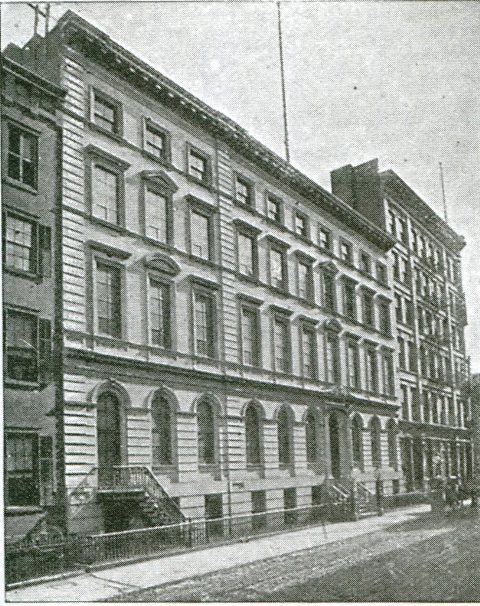

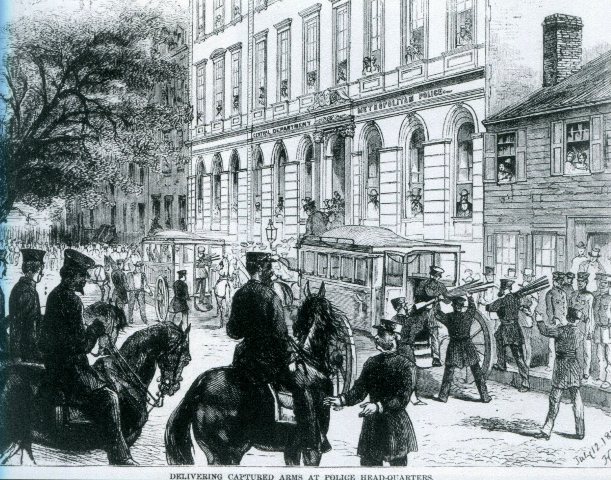

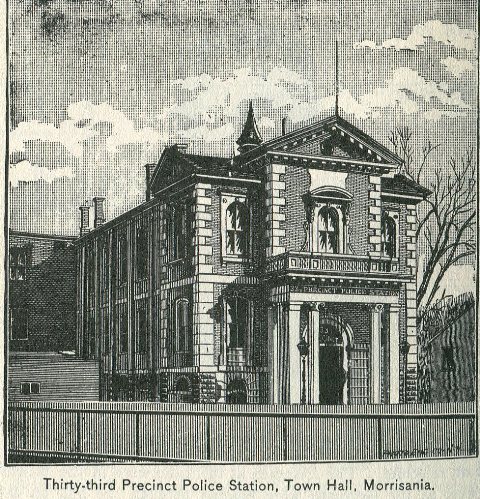

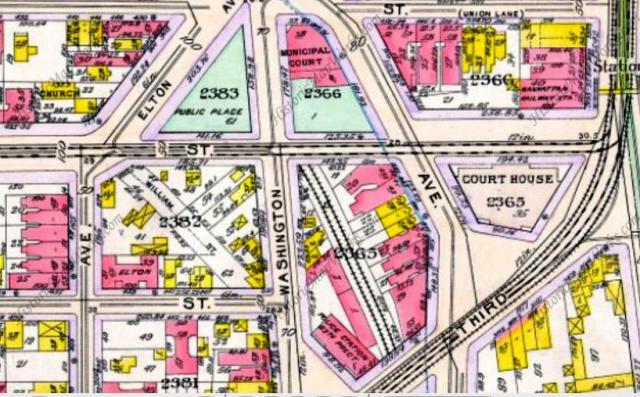

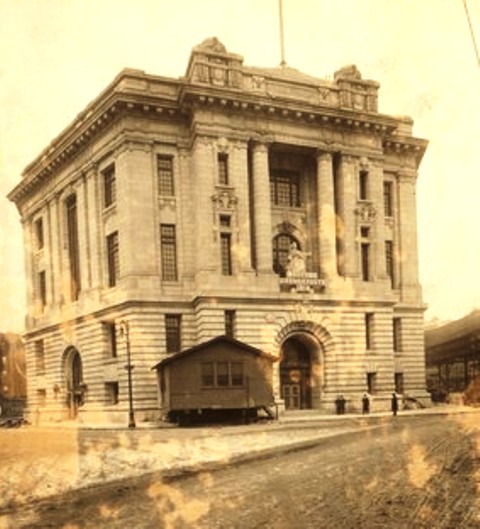

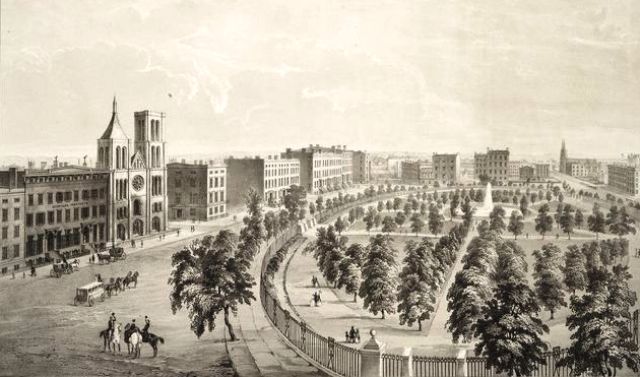

The sparrows at Union Square were under the watch of Policeman John T. Shaw, who was also in charge of the grounds. Policeman Shaw had been appointed to New York’s police department on April 19, 1856, and was attached to the 18th Patrol District station house at 319 Second Avenue, near East 22nd Street. Back then, each ward of the city had a patrol district of the same number. In addition to the main station house, the patrol district of the 18th Ward also had day stations at Union Square, Stuyvesant Square, and Madison Square.

According to Policeman Shaw, who kept a record of the birds’ activities, the newly arrived male sparrows immediately began fighting with some wrens who had occupied a little wooden house in the trees. In 14 minutes, the wrens were gone and two pairs of sparrows had moved in. Five weeks later, 9 baby sparrows arrived. By the fall of 1867, there were about 600 sparrows in Union Square. A year later, Policeman Shaw had about 1,500 birds under his wing.

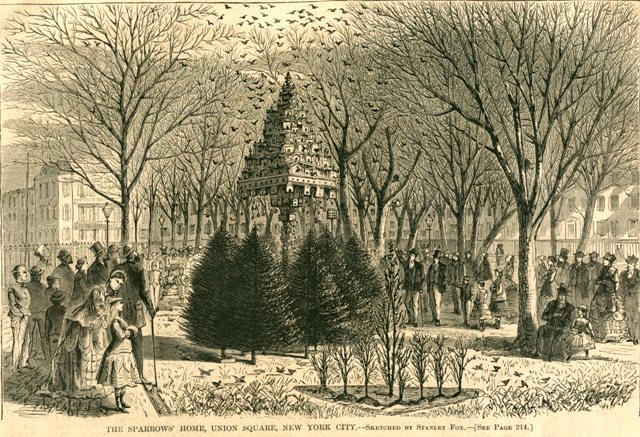

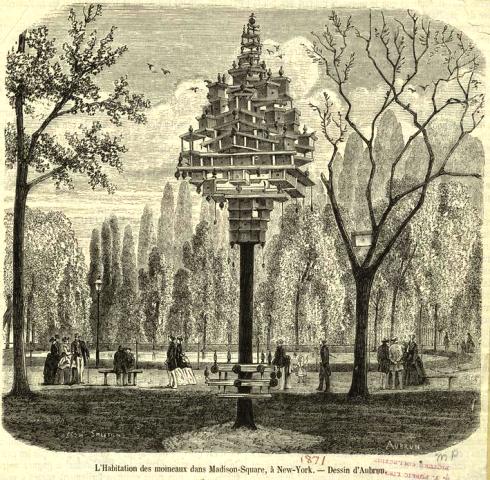

When the first group of sparrows arrived at Union Square in 1866, there was but one small birdhouse in the square. By that summer, 100 more “single-family” birdhouses appeared. A year later, some very elaborate and large multifamily sparrow apartments starting showing up in Union Square, Madison Square, and other parks.

These expensive homes had little wooden signs that read “Sparrows’ Hotel,” “Sparrows’ Pavilion,” and “Sparrows’ Chinese Pagoda.” Soon, an entire village appeared in the treetops, including a Sparrows’ Doctor Shop, Sparrows’ Restaurant, and Sparrows’ Station House. Although the birds frequented all the parks in the city, they seemed to make Union Square their headquarters.

The miniature palaces were a gift of a well-known New York physician, and were painted and adorned by his daughters, Laura and Blanche. The hotel reportedly had 8 rooms, the house had 5, and the pavilion boasted 50 apartments. There was also a rustic thatched cottage that housed 36 pairs of birds. But even with close to 160 birdhouses in 1868, that still wasn’t enough, and solicitations were taken for more sparrow hotels of greater dimensions.

In 1875, for example, New York Alderman John H. Zindel offered a resolution instructing the Board of City Works to furnish and put up 50 birdhouses in the City Hall Park, and to furnish two bins of ground food for the sparrows. Funds for the houses and food – not to exceed $50 — was appropriated from the Contingent Fund.

Inside the homes were nests made of hair, grass, cotton, and feathers, all laid on a foundation of courser materials like twigs and straw. The sparrows would not allow any other kind of bird to move in – they would attack and expel intruders with great fury. They were not even hospitable to their own kind, allowing homeless neighbors to freeze to death in winter rather than inviting them inside.

In addition to inchworms, the sparrows also ate yellow caterpillars, grasshoppers, earth worms, and other insects. They would also pick from the oats that fell from the horses’ feed bags. In winter, Policeman Shaw fed them cracked rice — they went through two barrels in the winter of 1867. He also put some short pieces of plank wood in the fountain so that they could drink and bathe.

The city also encouraged people to feed the birds and provide them with water in the winter. In 1870, The New York Times published instructions for providing water:

“Water should be placed in milk pans or other shallow broad-bottomed vessels, wherein it should be poured three or four inches deep, with little bits of blocks or boards floating on the surface, on which the birds will light and easily satisfy their wants.”

Too Much of a Good Thing

By the late 1870s, New Yorkers were up in arms over the prolific birds, which had all but chased away the native songbirds. Some suggested tearing down the cozy little homes or shooting the birds. At one time the Department of Agriculture was so exasperated over the prolific flocks that a campaign was sponsored to poison the little birds.

In 1884, a committee of the American Union of Ornithologists declared the sparrow a nuisance, thief, and murderer, and recommended it be exterminated. In 1886, a New York State statute was passed making it illegal to feed or shelter the birds — the penalty was up to a year in prison and a fine up to $1,000. And in 1900, the Lacey Act — a Congressional law that addresses illegal wildlife trade to protect species at risk and bars importing species found to be injurious to the United States — prohibited importing English sparrows.

Despite all efforts to eliminate the sparrow from America, the bird survived and thrived. In September 1960, the year the Department of the Interior removed the bird from the list of banned species — The New York Times declared that the 100-year war on the sparrow had ended, and that, for better or worse, it was one of the most abundant of North American birds.