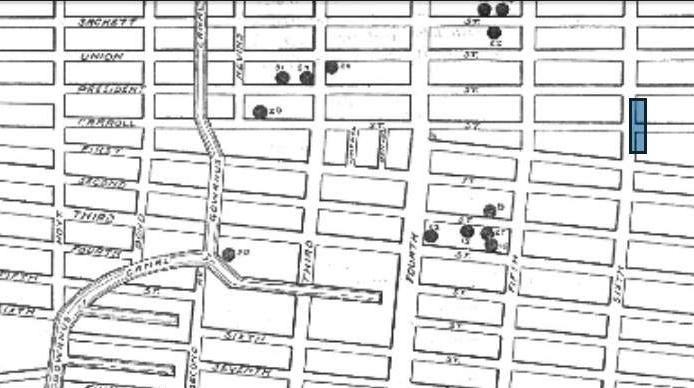

This pirate cats tale of Old New York begins on June 6, 1916, when 10-month-old John Pamaris of 53 Garfield Place and 2-year-old Armanda Schuccjio of 5014 7th Avenue — two children in the Italian community just east of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn — were reported to the New York City Health Department as having symptoms of polio (then called “infantile paralysis”).

These two reported cases, along with four more cases reported on June 8, served as a warning of the impending polio epidemic.

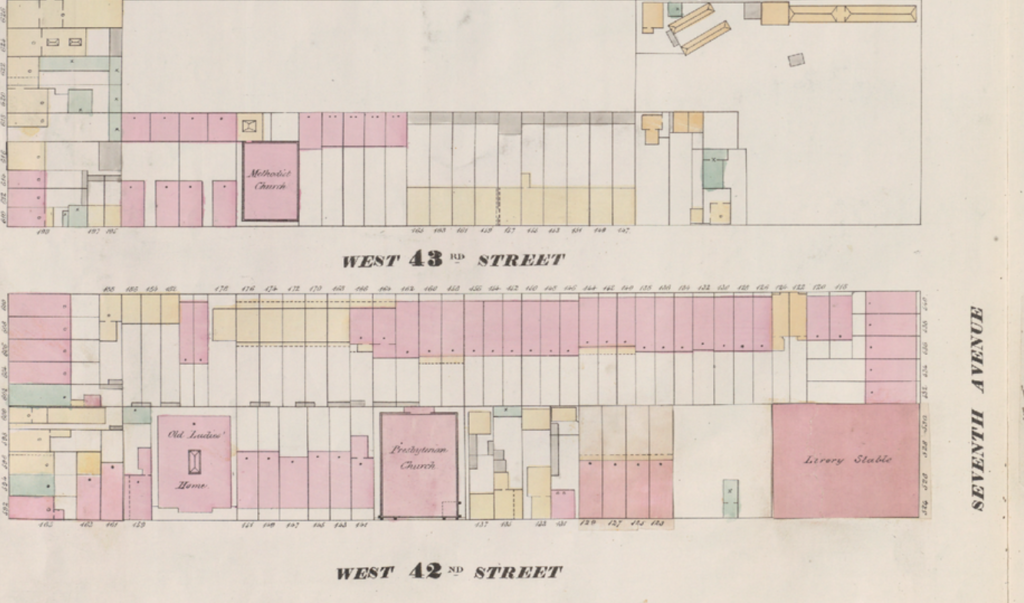

Within a few weeks, there were 24 cases in Brooklyn, most of them in the area bounded by 7th Avenue and Third, Degraw, and Nevins streets. By the end of June there were 646 reported cases of polio in that borough, plus about 150 cases throughout the other boroughs.

At the time, there was no good theory for how polio was spread. Since the outbreak began in the Italian community, some, including New York City’s health commissioner, Dr Haven Emerson (a great-nephew of Ralph Waldo Emerson), thought that the disease had been brought to America by Italian immigrants.

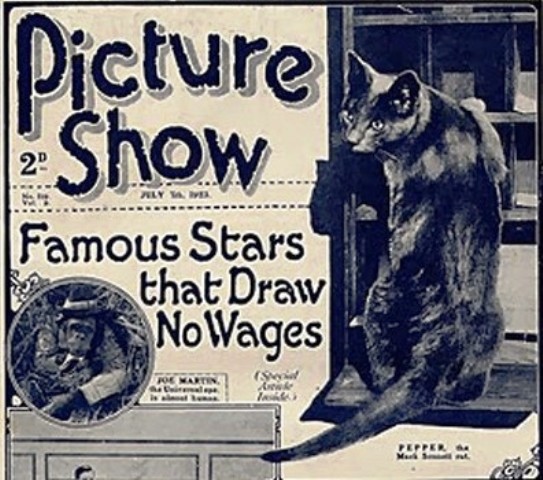

Others in the health community speculated that it was spread by insects, while some early reports suggested that domestic cats and dogs were to blame. For example, in an article in The New York Times on July 30, 1916, people were advised to wash their pet cats and dogs in a two percent solution of carbolic acid (that must have gone over well with the pets).

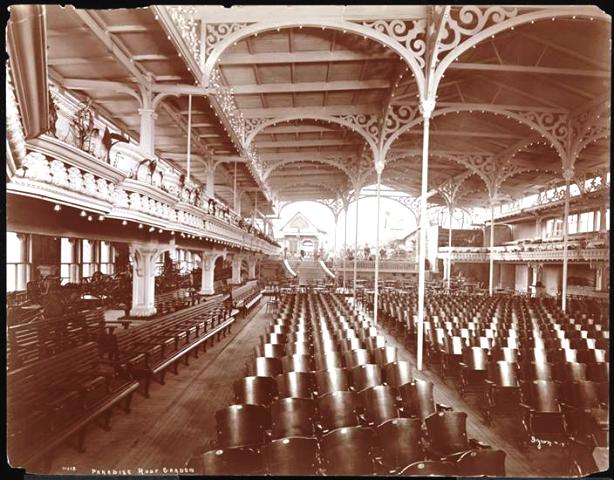

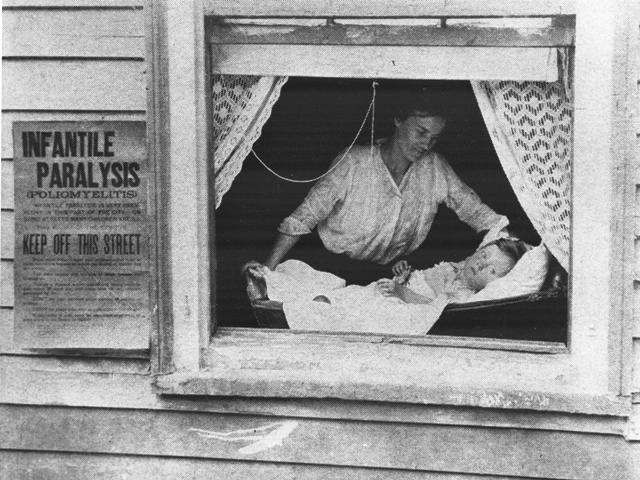

The 1916 epidemic caused widespread panic. Movie theaters and libraries were closed, meetings were canceled, public gatherings were almost nonexistent, and children were told to avoid water fountains, amusement parks, swimming pools, and beaches. Thousands of the well-to-do fled the city or sent their children to live with relatives in other states.

Many more people released their pets to the streets, where they were rounded up and put down. On July 26, the Times reported that the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) was sending up to 450 animals to the lethal chamber every day.

Despite all this killing of innocent animals, some domestic pets were able to dodge the bullet for an extended period.

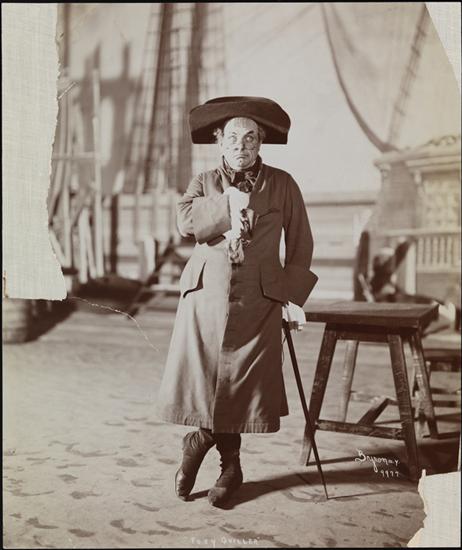

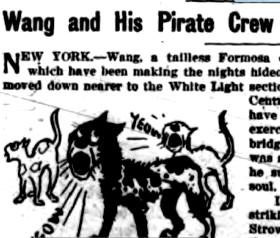

Wang and His Gang of Pirate Cats

Although he had probably been a domestic cat, Wang was a street-smart feline who knew how to survive. Described as a “mauve cat” with pink eyes, white feet, and no tail, Wang was the leader of a pack of up to 100 stray cats that haunted West 80th Street between Columbus and Amsterdam avenues during the brutal spring and summer of 1916. The press called them the pirate cats.

For three months, Wang and his posse defied the police, the SPCA, and the stray dogs. According to a policeman, the stray cats made their lair in a cellar on West 81st Street, where they spent the daylight hours in hiding (they also had a second escape home in a cellar near Amsterdam and 79th Street).

At night they kept all the residents awake with their howling as they moved from one janitors’ apartment to the other to steal food. The policeman suggested that the pirate cats howled so loud because of a new law that required residents to place tight lids on garbage cans.

Piotr Besanovitch, a janitor near Amsterdam Avenue, said Wang and six other pirate cats had entered his kitchen one night and stole a leg of mutton off the table. As the cats devoured the meat off the bone, Wang and a large black cat with yellow eyes and clipped ears stood guard outside the cellar door. Piotr said he tried using a few dogs to keep the cats away, but the dogs would only hide under the bed once the cats started howling.

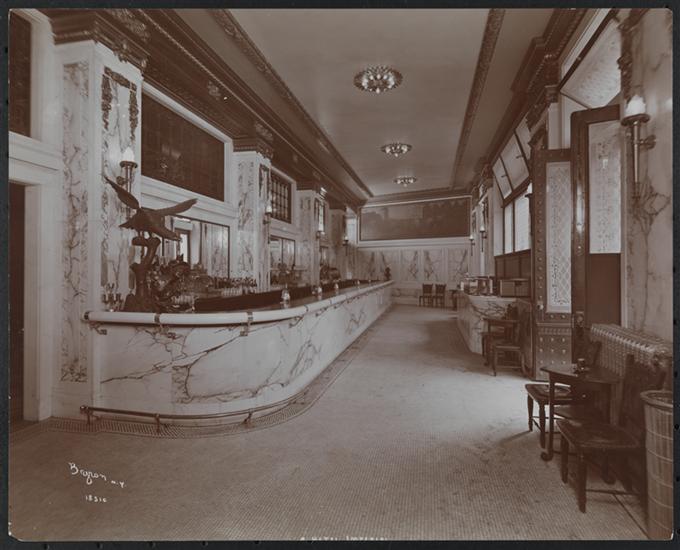

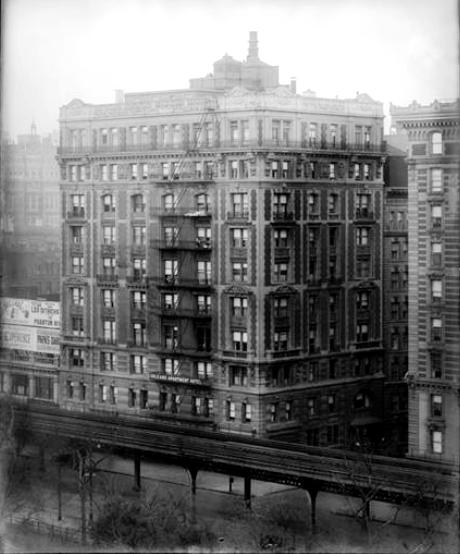

A day after The New York Times did a story about Wang, the king of pirate cats took his gang to Central Park West, where residents and guests at the Hotel Majestic reported that the cats were creating a nuisance in the area. Timothy Ebbitt, night house detective at the hotel, formed a search team of bell boys, night clerks, kitchen men, and a few scrub women with mops.

Near the 72nd entrance to Central Park, they saw Wang surrounded by about 30 other pirate cats. Wang arched his back in attack mode and then scurried away when Ebbitt threw some rocks his way. They were last seen by a policeman heading toward Broadway. I have a bad feeling, though, that they were really last seen at the SPCA animal shelter.

According to Thomas F. Freel, superintendent of the SPCA, more than 80,000 cats and dogs were collected off the city streets and disposed of in the lethal chamber by the end of July.

The epidemic also took a large toll on human life, with over 27,000 reported cases and more than 6,000 deaths in the United States — over 2,400 deaths were reported in New York City.

The Monkeys at Rockefeller Institute

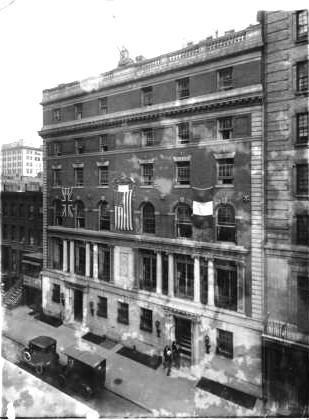

One modern-day theory is that the 1916 epidemic was caused by a “mixed virus” (MV strain) of polio that had escaped from the Rockefeller Institute, which was then located just three miles from the epicenter of the outbreak at 63rd Street and York Avenue in Manhattan.

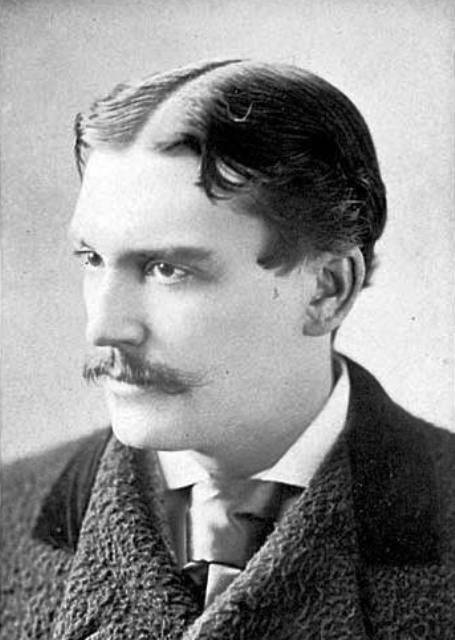

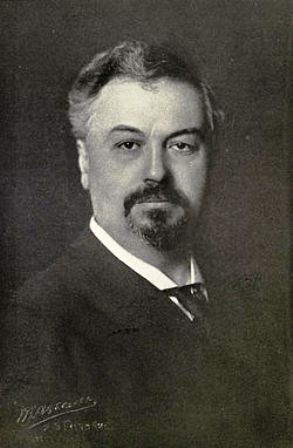

It was here that Dr. Simon Flexner, the first director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, was conducting studies by transferring spinal cord tissue containing the

poliovirus from one Rhesus monkey’s spinal cord to another.

Although Dr. Flexner’s research led him to conclude, falsely, that poliovirus entered the body through the nose, the “germicidal substances” that were present in the blood of the monkeys and which had survived polio were later discovered to be antibodies for the disease.

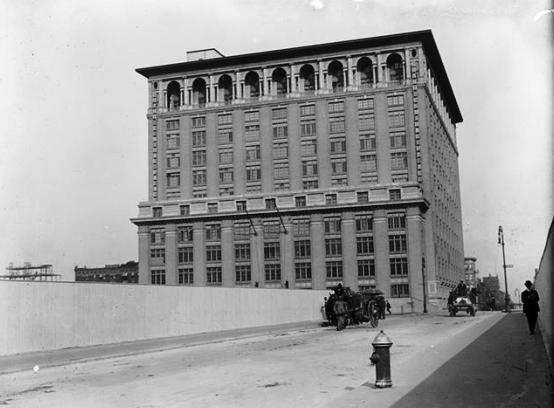

The Rockefeller Institute

In the early 1800s, Peter Schermerhorn, a merchant and shipbuilder, bought property bounded by 63rd and 68th streets and Third Avenue and the East River.

Following his death, the Schermerhorn farm was turned over to his son William, who lived there until 1860, when he bought his mansion at 49 West 23rd Street.

Forty years later, in 1901, John D. Rockefeller’s first grandchild, John Rockefeller McCormick, died of scarlet fever. In reaction to his grandson’s death, the senior Rockefeller decided to found an institute devoted to research in medicine.

In 1903, when William Schermerhorn died, Rockefeller paid $700,000 for the old farm, which comprised three full lots of unimproved land. Here, in 1906, he opened the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, the first biomedical research center in the United States.

In 1955, the Rockefeller Institute expanded its mission to include education. Ten years later, the institute changed its name to Rockefeller University. Today, the university is a world-renowned center for research and graduate education in the biomedical sciences, chemistry, bioinformatics, and physics.

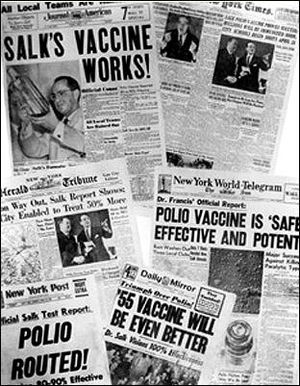

On April 12, 1955, Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., declared to the world that Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine was “safe and effective.”

The announcement was made at the University of Michigan, exactly 10 years to the day after the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was diagnosed with polio in 1921 at the age of 39.

Although the vaccine arrived 40 years too late for thousands of people, cats, and dogs, today naturally occurring polio is nonexistent in the United States and has been nearly eradicated from the world.